Cemeteries are designated consecrated places in which the dead are deposited. The word comes from the Greek koimeterion or the Latin coemeterium, meaning “to lie down to rest” or “to sleep.” This usage alludes to the Christian belief in resurrection; but burial is not only a Christian practice — it is found all around the world, as is cremation and other ways of remembering those who have died and disposing of their bodies.

Land was set aside in 1797 for a graveyard next to St. James Church, Toronto’s first Anglican Church, built 1803-4, and the site of today’s St. James’ Cathedral. Some of the original gravestones can be seen near the entrance to the Cathedral. Thousands of burials had taken place on very small plots of ground; these places filled up. St. James churchyard had burials five or six coffins deep and even buried vertically. At the same time, Toronto became more crowded, densely packed and real estate values rose.

St. James Cemetery is Toronto’s first “garden cemetery”. France’s Pere-Lachaise (1804) has become known as the first of the “garden” cemeteries. It was named after the confessor priest of Louis XIV and is probably the most celebrated burial ground in the world. It became known around the world for its size and beauty — landscaped and fashioned with pathways for carriages. Paris set the fashions for clothes and graveyards and North America followed.

The first garden cemetery in North America was Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts, consecrated in 1831. It was planned as an “oasis” on the outskirts of the city and defined a new romantic kind of cemetery with winding paths and a forested setting. It was an immediate success and inspired many other garden cemeteries across North America and in Britain.

From the College we drove to the Cemetery, and the ‘city of the dead’ was, perhaps, the finest thing I saw in or near Boston. The guide-books say that you may wander about through the walk a distance of forty miles without twice visiting the same spot. It is almost one’s beau-ideal of a cemetery, neatly kept, thickly studded with trees, quiet and remote from all noise or bustle; if a man has a vein of tender melancholy in him, this is precisely the place to move him. Globe September 19, 1850

In 1832, the London Cemetery Company opened the first public cemetery at Kensal Green. It was made up of 54 acres of open ground and was outside the city at the time. By moving the dead out of the city center to places like those beside the Don, these “rural cemeteries” allowed for much larger burial grounds and ceremonially removed the dead from the immediate realm of the living.

1. out in the country, away from the town centre

2. careful siting, use of topography: shady glens, vistas

3. complexity: cities of the dead.

4. civilized nature: herbs, shrubs, understory, canopy (to a naturalist’s eyes)

5. rolling lawns (manicured grass), shrubs, groves of trees (arboretums),

6. water features; a lake, pond or stream

7. recreations of picturesque architecture

8. elaborate entrance gates that mark the fact that you’re leaving the mundane world behind.

9. winding roads and paths

Parks were non-existent so poor people, and even their “betters”, flocked to cemeteries for picnics, for hunting and shooting and carriage racing, Sunday carriage drives and casual strolls.

The trend spread beyond the concept of the landscaped cemetery to include grand and well-designed city parks, many linked to the pioneering work of Frederick Law Olmsted, the father of American landscape architecture. Olmsted and his visionary colleagues designed parks as famous as New York’s Central Park and Boston’s Emerald Necklace, and extensive park systems were created in Buffalo, Milwaukee, and Chicago. Toronto’s High Park, Queen’s Park, Riverdale Park. They also laid out the plans for grand and green college campuses across North America such as that at the University of Toronto. As parks arose, the recreational use of the open areas of cemeteries diminished in importance.

John G. Howard laid out the cemetery grounds in 1844. The cemetery was necessary as the burial ground around the cathedral itself, in use since 1797, was out of room. At that time most of the city’s population of 18,000 lived south of Queen Street and the cemetery location at Bloor and Parliament Streets must have been regarded as being well out in the country. According to records kept by the rector of St. James, Henry James Grasett, the church wardens bought the grounds in the early summer of 1844. They purchased 60 acres lying between the Cayley property and the Park from William Henry Boulton for 250 pounds. They planned on spending an additional 2,500 pounds laying it out and landscaping it. In the first few weeks workmen, removed more than 1,000 stumps and tastefully laid out, winding walks under the superintendence of J.G. Howard Esq.” They planned a chapel: On a little knoll, a short distance fm. the entrance, timber being prepared for erection of a small chapel 23 x 40 ft. but the Chapel of St. James the Less wasn’t built until later. The chapel opened for funerals in 1861. (It served for many years as a Parish church to the neighbourhood.)

The first grave dug in St. James’ Cemetery was on the 14th September, 1844, for the burial of Elizabeth Whitewings, a baby girl two months old. (Globe, Jan. 1, 1886) Bishop John Strachan consecrated the ground on June 5, 1845. By the end of the month there were already 20 burials here. St. James Cemetery was built just in time for Black ’47 and the influx of refugees from the Potato Famine. Over 300 buried here and about 800 at the Catholic Cemetery on Power St. (Globe, Feb. 2, 1848). The new immigrants bought typhus and cholera with them on their “coffin ships”. Cholera returned in 1851, 1853, and 1854.

… the mortality since the commencement of the present month, has been about five times the average rate. There is nothing in this fact to create undue alarm, but it is well that it should be stated, in order that the public may see the necessity of using every precaution, in regard to diet, cleanliness, etc., so long as the seeds of disease are abroad in the atmosphere to a more than usual extent.” … This shows a very remarkable increase on last week, the average then being about twelve a day, while now it is twenty-eight. We believe that the excitement and intemperance attending on the election are partly the causes of the increase. Globe July 31 1854

The city burial grounds vie with the city parks in their attractions, particularly St. James’ Cemetery, the Necropolis, Mount Pleasant cemetery, and St. Michael’s Cemetery, are thronged with people out for a walk, sauntering along the paths or resting in the shade. St. James’ Cemetery especially is popular in this respect. It is nearer to the centre of the city than any other, it has well kept paths, is better shaded than any other, and has the advantage of the beautiful and historic Castle Frank Road, which as a drive or walk is not excelled in the city. After the hurry and worry of the week, a Sunday afternoon spent in quietly sauntering about St. James’ Cemetery is a genuine treat. In view of the popularity of these places, the public will receive gladly the announcement of the improvements to be made in them. In the majority no very great changes can be expected, as they have been laid out, and little remains to be done except to maintain the existing state of affairs and make improvements in the details where possible. (Globe, April 15, 1881)

In 1887 the Rosedale creek trunk sewer was built and a road allowance surveyed beside the sewer. The road allowance was 66 feet wide and ran two miles from Yonge to the Don River. The Cemetery fenced its property along the route of the new road. The new road transformed the Rosedale Valley ravine. (Globe, March 12 1892).

Toronto’s first Roman Catholics were buried in the graveyard of St. Paul’s Church, built in 1822 but that burial ground too filled up quickly, especially during the Potato Famine (1847-1850). The risks to public health came not only from the dank odors of the churchyards but from the very water the people drank. In many cases, the springs for the drinking supply tracked right through the graveyards.

Mount Hope Cemetery on Erskine Avenue opened in 1900, as the city’s Catholic population grew. Author Morley Callaghan, hockey pioneer Francis “King” Clancy and wrestling promoter Frank Tunney are among the historical figures interred at Mount Hope.

Further growth in the Catholic population after the Second World War necessitated the opening of Holy Cross Cemetery (1954), Resurrection Cemetery (1964), Assumption Cemetery in 1968 and Queen of Heaven Cemetery in 1985.

Toronto commuters and visitors hurrying through the subway’s main hub at Yonge and Bloor probably have no idea that it was once the site of another kind of “underground”: Potters Field or Strangers’ Burying Ground opened in 1825 but closed down a mere thirty years later. The bodies were reinterred at the Necropolis in Cabbagetown, a less central location. Potter’s Field, also called the Strangers’ Burying Ground, was opened in 1825 on Yonge Street, in Yorkville, opened in 1825 and was incorporated in 1826. it comprised six acres of land and was managed by Trustees. By an Act of Parliament, it was closed last year, when the Trustees purchased from the late proprietors, for the sum of 2,750 pounds. Globe, Dec. 13, 1856

The risks to public health came not from the dank odours of the graves but from the very water the people drank. In many cases, as in Yorkville’s Potters Field, the springs for the drinking supply tracked right through the graveyards. The call for the establishment of cemeteries away from the population center became louder after major typhus and cholera epidemics killed many immigrants and Torontonians too.

Toronto’s first Jewish cemetery, Holy Blossom, was established in 1849 in Leslieville. It closed in 1930.

The Necropolis’ “Resting Place of the Pioneers” was opened in 1850 to replace Potters Field. It is the final resting place of Joseph Bloor, George Brown, William Lyon Mackenzie and George Leslie, among many others.

TORONTO NECROPOLIS (excerpts from notice announcing its opening)

In the selection of a piece of ground for the formation of the Toronto Necropolis, the Directors endeavoured to keep in view, and secure certain advantages, which it appeared to them desirable, that every Cemetery should possess. The advantages referred to are the following, viz. – 1st. Amenity or beauty of situation. 2nd. Proximity to the City, or convenience of access, combining at the same time, with that peaceful seclusion which all admit to be so appropriately associated with the Grave, or the resting-place of the remains of departed relatives and friends. 3rd. The highest attainable security that the remains therein deposited shall continue undisturbed, and not liable to be removed or intruded upon, in any way; and this at such a moderate expense, as might be within the reach of all classes of the community.

..beauty of situation…solitude and retirement…a convenient distance from the city, and at the same time is as secluded and retired as if it were at the distance of several miles…(Globe, July 27, 1850)

By the early 1880s new city parks and the Horticultural Gardens (now called Allan Gardens) were beginning to outcompete the cemeteries as they offered more conveniences, like drinking fountains and washrooms, along with picnic tables – more convenient than tombstones.

Mount Pleasant Cemetery was opened in 1875. Among the luminaries buried on the grounds are former prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King and pianist Glenn Gould.

By Joanne Doucette

While researching material for an upcoming book on the history of Toronto’s golf courses, I found myself with a huge amount of material even for one small golf course — that on Mugg’s Island. Every writer has to know how to cut and what to leave in and then find an editor to cut even more! Some suggest that I should just “stick to golf” and leave out some of the more controversial aspects of sports history such as anti-Semitism, racism and sexism. Some suggest that to explore these is just “identity politics”. Even the largest social media site will not allow me to publish what I’m putting here today as they consider it offends community standards. But I’m plunging ahead because I need your feedback. Read on!

Muggs Island, also known as Mugg’s Landing, is part of the group of Islands collectively known as “Toronto Island”. Landfill operations had expanded the island from 11 to 47 acres of sand and brush by 1920. Taking advantage of this, William George Whitehouse, a young English engineer who lived on Centre Island, laid out a makeshift 18-hole golf course on Mugg’s Island in 1921.[1] It lasted only a few short summers. However, it wasn’t the first make-shift course there.

“It was a group of campers, in fact, who gave Mugg’s Island its name. In the 1880s four carefree bachelors – Chester Hughes, Jack Crean, Warring Kennedy and Jack Lye (who later became the Monarch of Mugg’s) – pitched their tent near one William Burns’ icehouse. The lads used to row, paddle or sail to work each day. One time, when rowing back from the city, they spotted a sign floating on the water, which had been tossed out after a play at the “Royal” that had closed. They towed the cast-off sign to their tent site and proudly erected it. The name of the play – and subsequently of their camp and its wild little island – was “Mugg’s Landing.”[2]

In the 1890’s John George “Jack” Lye, and his friends got permission to build a cabin on Mugg’s Island. The young men also built their own nine-hole golf course there – cutting holes in the sand with their jackknives just as Toronto Golf Club members were doing in the East End. The Mugg’s Island golfers were young, but not poor boys. They were the sons of Toronto’s elite, some of whom belonged to the Toronto Golf Club, like Colonel Sweny and the Cassels, also had summer cottages on the Island. Lye recalled, “A group of young fellows who chummed around together, including our leader Warring Kennedy and myself, were asked by Warring’s dad, Mayor Kennedy, to build a camp on the island and to keep away undesirables. This we undertook to do.”[3]

However, after World War One, Mugg’s original stopped coming, leaving “King John” Lye to rule Mugg’s Island alone. The golf course he and his friends laid out had not been used since the young men went off to war in 1914-1918. Some, such as Chester Hughes, never came back, dying in the trenches. Their course disappeared into the tall grass and poison ivy. Recalled young golfer George Hevenor, “It wasn’t really golf. We just chipped balls out of sand into tin cans.”2 Later, as a member of the Summit Golf Club, Hevenor won the club championship four times. Alongside representing Canada on two occasions as a member of Canadian Seniors Golf team, Hevenor also became a director of the Royal Canadian Golf Association. Not bad for a kid whose early experiences of the game were fostered on Mugg’s Island.

However, the story was far from over. Islanders have a well-earned reputation for being persistent. If at first you don’t succeed, try and try again – at least six times!

In 1928 a spokesman for Stanley Thompson, proposed a nine-hole public course on Mugg’s Island at a cost of $45,000. The course could also be expanded to 18 holes by extending the layout across Long Pond using a pull-boat to get golfers across, but plans fell through.

In 1930 William James Sutherland, secretary of Centre Island’s Businessmen’s Association, again proposed building a nine-hole course on Mugg’s Island to the City of Toronto Parks Committee. Sutherland owned the Hotel Manitou “for Gentiles of refinement” and the proposal was on letterhead with that slogan on it. Alderman Sam Factor immediately tackled the anti-Semitism. By this time the Jewish population of Toronto was about 50,000, and not to be ignored. Other city politicians opposed the proposal. Nevertheless, the City of Toronto Parks Commission negotiated with golf architects Millar and Cumming to lay it out.

That spring the T.T.C. opened a miniature golf course at Hanlan’s Point. It lasted only one season.

Three years later “Gentiles Only” signs went up at Balmy Beach and Jewish and Italian men and women fought Nazis and Swastika Club members in a public park — the infamous Christie Pits Riots. That year Hitler became Chancellor of Germany and the first Nazi concentration camp, Dachau, opened.

By 1936 when the Toronto Island Ratepayers’ Association met in Hotel Manitou and Sutherland again lead the move to build a nine-hole course on Mugg’s Island, Sam Factor was Toronto’s only Liberal Member of Parliament. Lobbying for the course continued through 1937, but anti-Semitism left a sour taste that the City of Toronto just wouldn’t or couldn’t swallow as World War Two loomed on the horizon. However, other golf clubs also barred Jews as well as Black Canadians and other visible and not so visible minorities.

In 1939 George McCordick proposed building a 3,000-yard nine-hole course and a clubhouse on Mugg’s Island. The Parks Committee turned him down. By this point “King John” Lye was old. The golf course he and his friends laid out had not been used since the young men went off to war in 1914-1918. Some, such as Chester Hughes, never came back, dying in the trenches. By 1944 when King John Lye died there were few traces of their Mugg’s Island course left.

In 1949 Parks Commissioner Walter Love began negotiating to buy the old York Mills golf layout for a municipal golf course.The Parks Commission considered other sites, including Mugg’s Island, but a bridge would be needed to Centre Island and the plan fell through.

In 1956 the new Metropolitan Toronto took over control of the Toronto Islands. There was again a proposal that Mugg’s Island be turned into a golf course and, again, it got nowhere.

In 1963 Metro Parks Commissioner Thomas “Tommy” Thompson created an amusement park at Centre Island with a miniature golf course. This mini-putt still operates.

[1] Toronto Star, June 15, 1921

[2] Sally Gibson, More Than an Island (Toronto: Irwin Publishing, 1984), pp. 98-99

[3] Toronto Star, June 18, 1966

By Joanne Doucette (liatris52@sympatico.ca)

This is the last of this series of posts although I will edit and update the posts as more info and material surfaces. This post contains

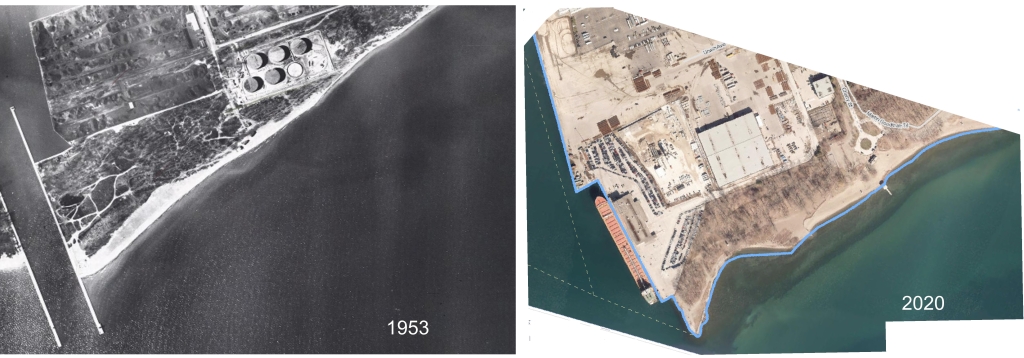

1. Aerial photos

2. Maps

3. City Directories

By Joanne Doucette (liatris52@sympatico.ca)

This posting contains:

Before and after the construction of Dundas Street East.

By Joanne Doucette (liatris52@sympatico.ca)

In this post there are:

By Joanne Doucette (liatris52@sympatico.ca)

This posting includes: