THE FENCE

How did the Craven Road fence come to be? Why is it there? What is the big deal anyway?

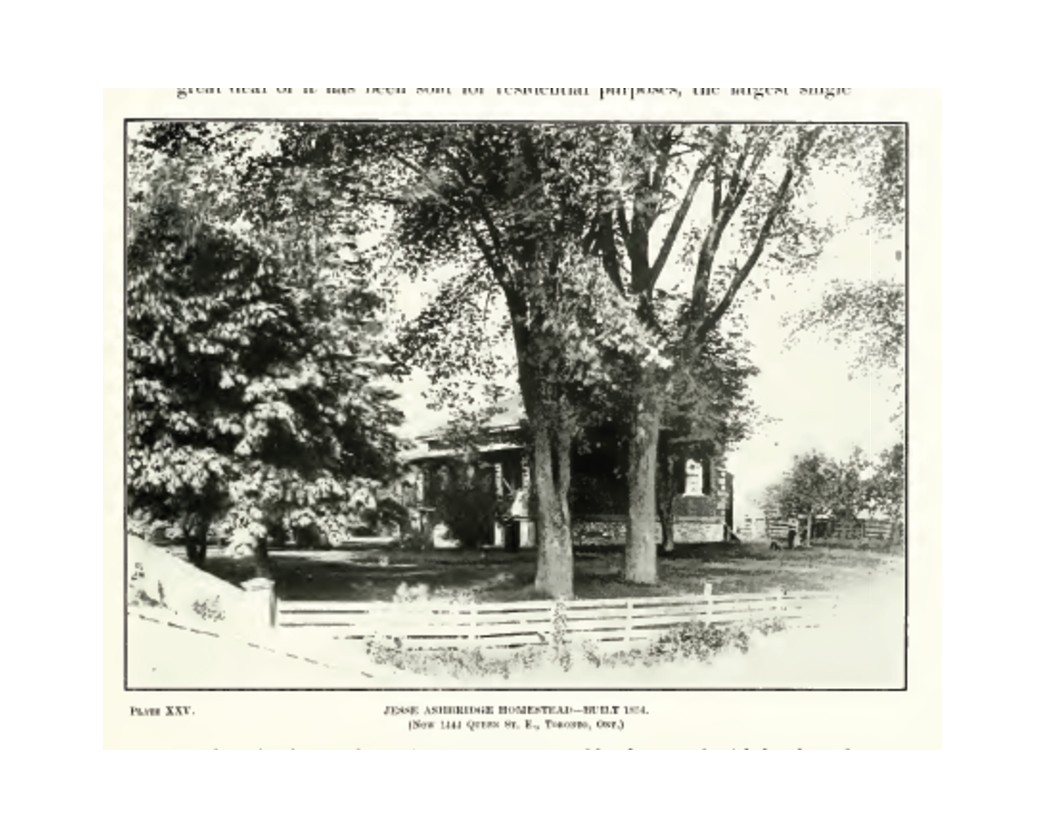

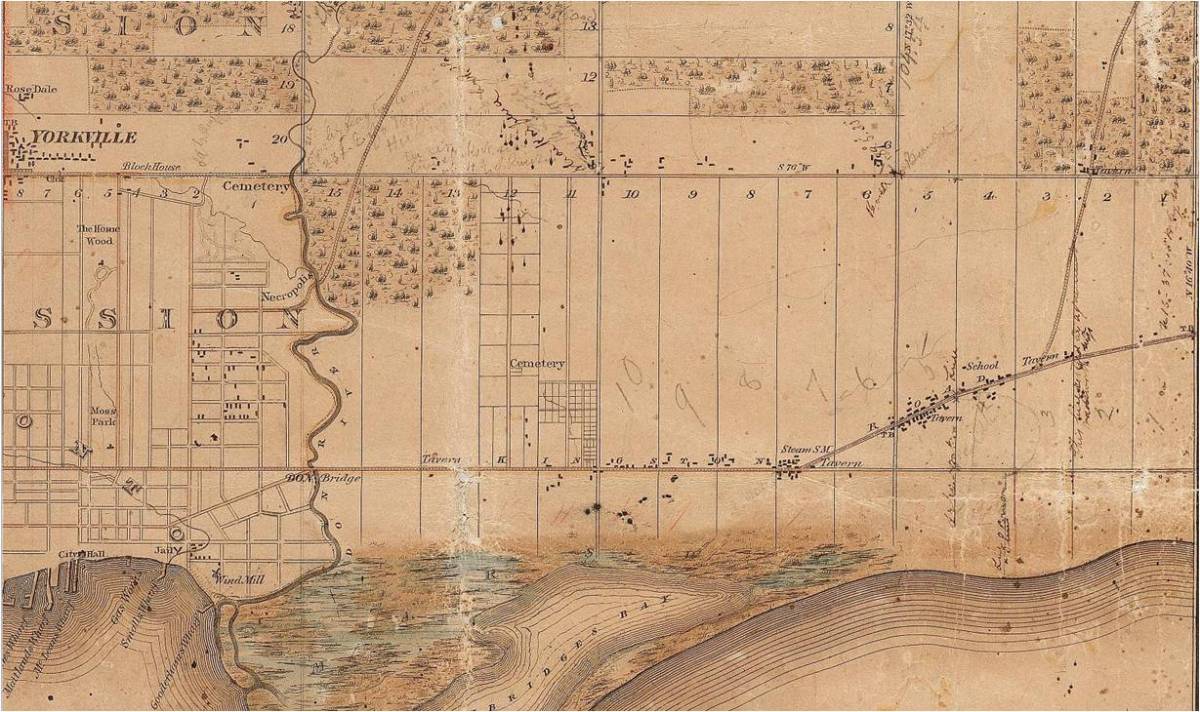

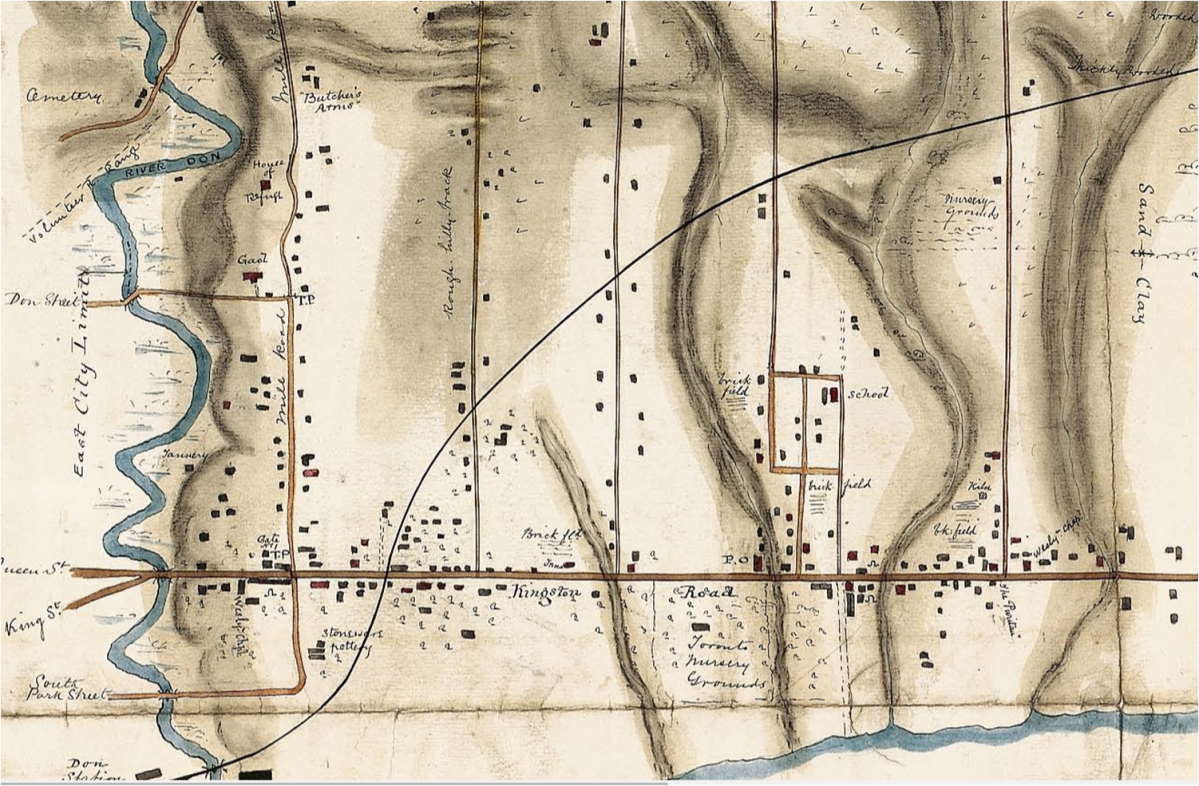

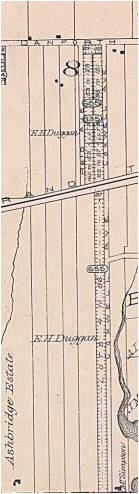

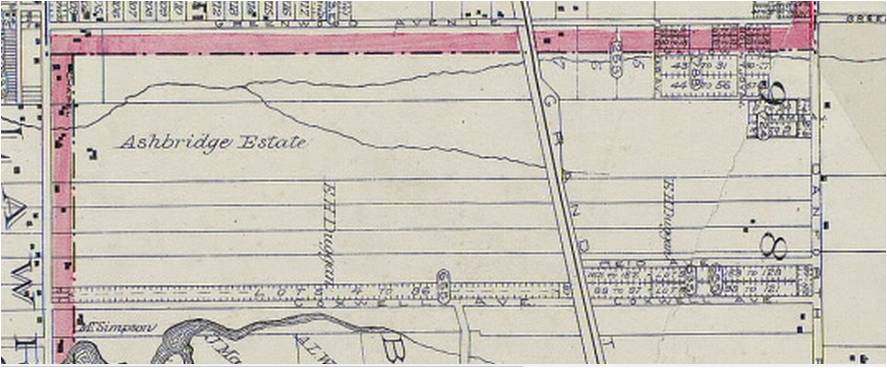

Fences go back to the first settlers. They brought the idea of the fence with them, splitting cedar stumps to make rail fences that snaked over the landscape, cutting the earth into neat rectangles and walling out the forest with stout barriers made of the giant stumps of the White pines they destroyed for their fields and for the masts of the British navy. The Ashbridge Estate stretched from Queen Street to Danforth Avenue and Ashbridges Creek flowed through it down to Ashbridge’s Bay. The Ashbridges lined the creek with fences to keep the cattle from polluting the water. What is now Craven Road was part of Lot 8, a long north south field running from Kingston Rd to Danforth (1st Concession), part of the original grant to the Ashbridges Family and their kin.

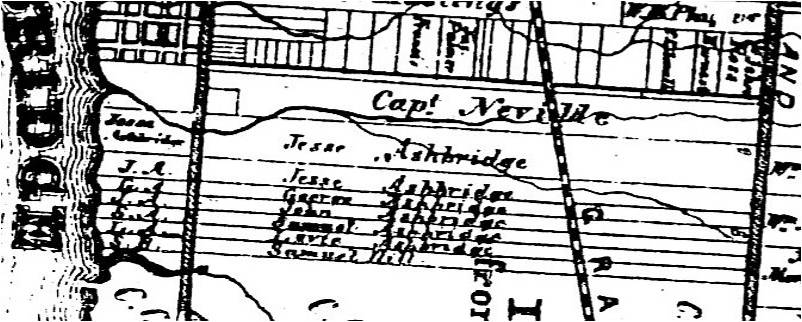

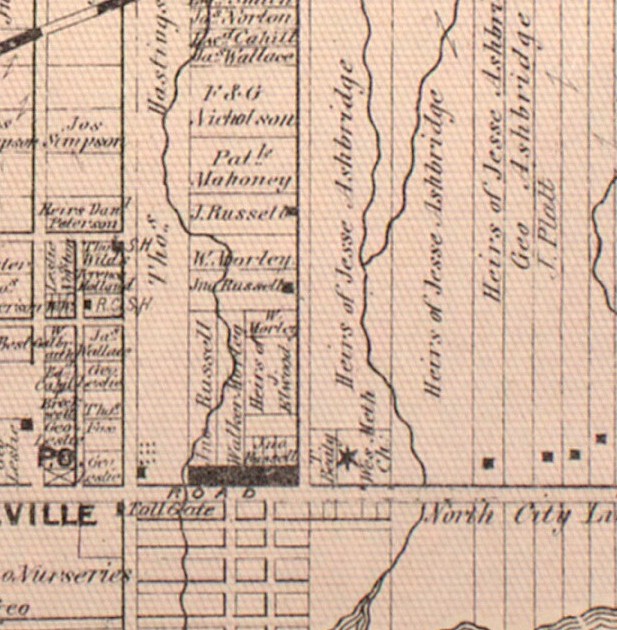

The first 200 feet east of Greenwood Avenue and the land west of it to Danforth Avenue were incorporated into the City of Toronto in 1884 along with a narrow strip 200 feet north of Queen to the Beach. The Ashbridges family passed down portions of the original estate to various descendents resulting in narrow strips of farm fields running north south from Queen Street, bounded by more fences. By 1861 Lot 8 was divided into five smaller farms as each heir got a piece. From east to west the lots belonged to:

- Samuel Hill,

- Levis Ashbridge,

- Samuel Ashbridge,

- John Ashbridge,

- and George Ashbridge.

West of that, Jesse Ashbridge and west of Vancouver Avenue, Captain Neville (part of this was later purchased by Jesse Ashbridge).

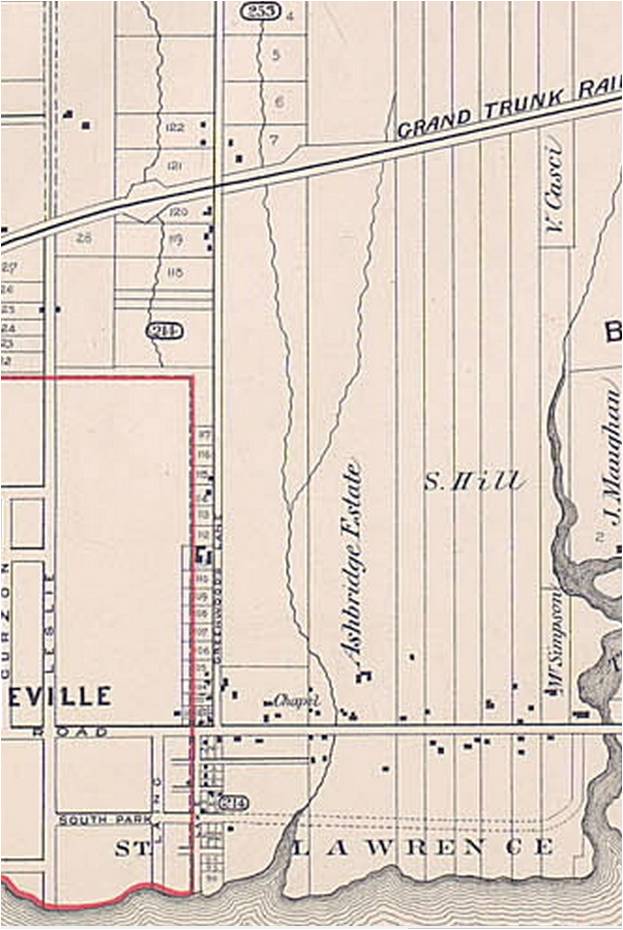

The farmers used deeply rutted, narrow farm lanes to drive their farm equipment onto these fields. The average cart road was 18 feet wide, but the average country road was 33 feet wide. The farm lanes ran beside the fences at the boundaries of the properties. When the properties were developed, a road network followed the pattern of the farm lanes and fences along the edges of these strips of farm field. These farm lanes became Coxwell Avenue, Rhodes Avenue, Craven Road, Ashdale Avenue, Hiawatha and Woodfield Road. An 1868 map shows Lot 8 as farm fields with sand and clay and as thickly wooded north of the railway line. The 1878 County Atlas map shows from east to west first lot Sam Hill, next two lots, no name, then J. Platt, George Ashbridge and west of that Heirs of Jesse Ashbridge.

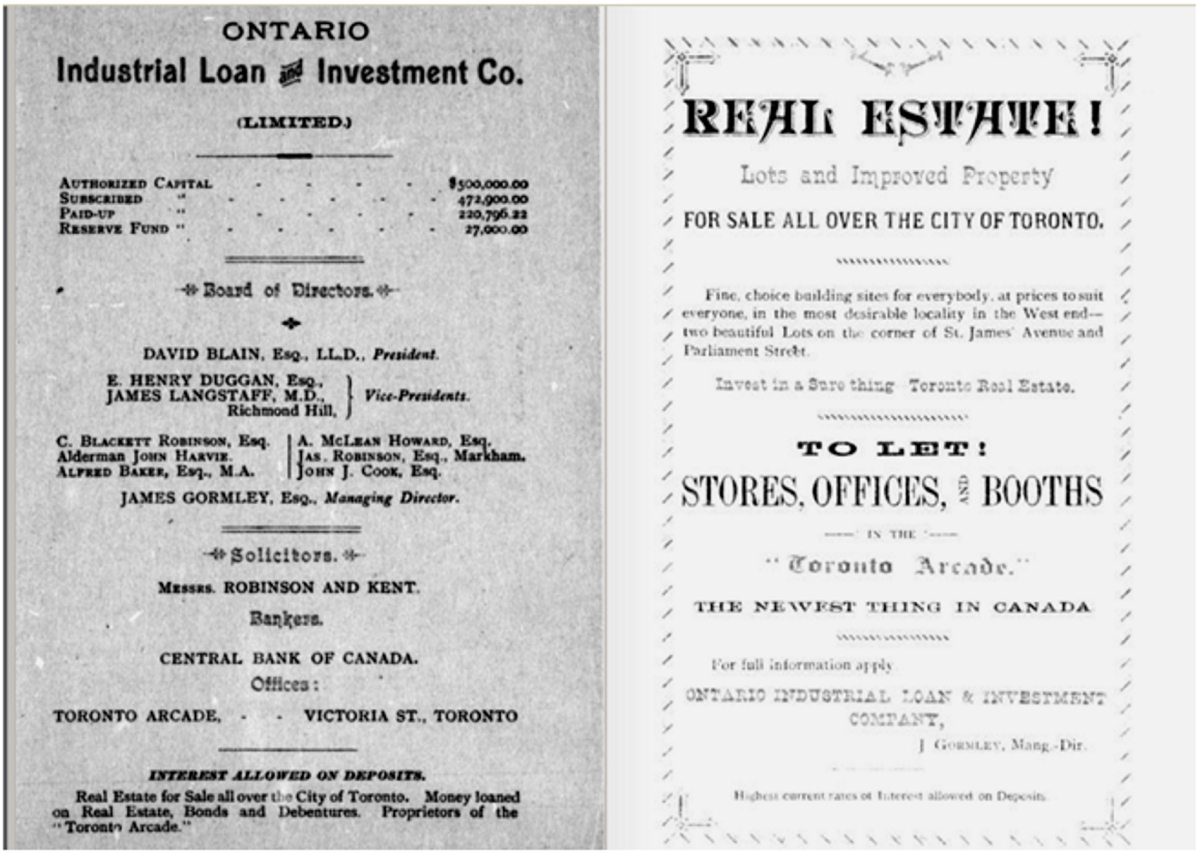

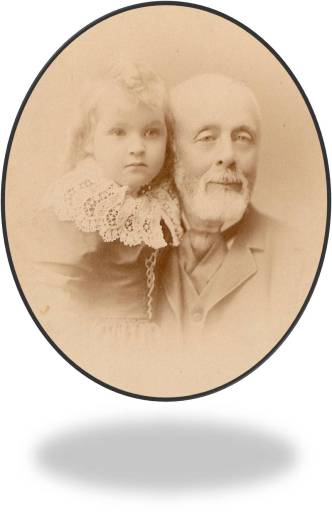

Speculators were counting on the expansion of Toronto to make their fortunes. One was Edward Henry Duggan, Vice President of The Ontario Industrial Loan and Investment Co.

Arcade Guide and Record, 1884

Arcade Guide and Record, 1884

Redwood Avenue marked the eastern boundary of the 1884 extension of the City of Toronto. Glencoe Avenue (now Glenside) ran through a brickyard, later used as a garbage dump. It was not filled in and used for housing until after World War II. In 1884 Goad’s Map shows everything east of the Ashbridge Estate to Coxwell as belonging to S. Hill (5 narrow farm fields formerly from east to west: Samuel Hill, Levi Ashbridge, Samuel Ashbridge, John Ashbridge, George Ashbridge.).

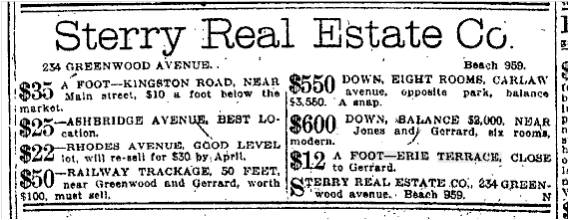

Goad’s Atlas, 1890 shows E H Duggan as the owner of the 5 narrow fields between Woodfield Road and Coxwell Avenue. The field immediately to the west of Coxwell Avenue had already been subdivided by E H Duggan into small lots and registered as Subdivision Plan 655 but not built upon. The lane on the west side will become Rhodes Avenue. The lane on west side of the lot adjacent will become Craven Road.

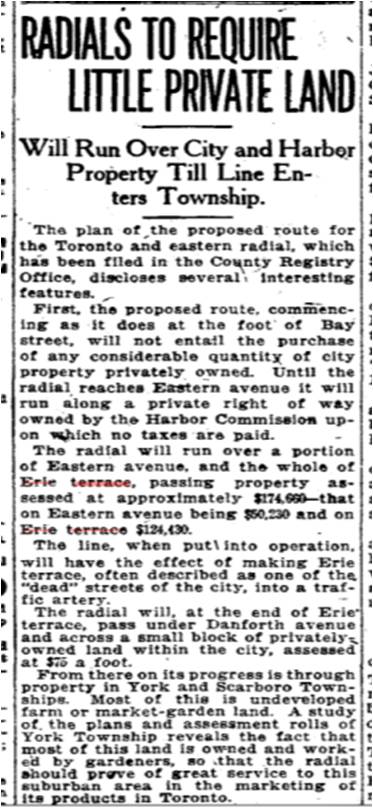

E. H. Duggan, real estate speculator and promoter, could be called the founding father of Erie Terrace. As a case before the Supreme Court of Canada in 1891 (Duggan v. London & Canadian Loan Co.) indicates, he was a bit of a “wheeler-dealer”. He was sued in 1891 for using trust funds to back real estate deals. Duggan was involved with the Toronto House Building Association which had developed Parkdale in 1875. One of the goals of the Association (later called the “Land Security Company”) was to allow low income families to own their own homes or perhaps more accurately to sell as many lots as quickly as possible to poor immigrants and make a lot of quick money. It made money by selling the lots but also because it held the mortgages on the lots.The Goad’s Atlas, of 1893 still shows that E H. Duggan had laid out Coxwell Avenue and Rhodes Avenue (Reid Avenue), but the lots had not been put on the market yet. The 1890s was a time of economic depression and he waited for better days and higher real estate prices even for this land outside of the City of Toronto. The City of Toronto’s boundary was east-west 200 feet north of Queen and 200 feet north-south east of Greenwood Avenue. He owned the land from the Ashbridge Estate over to Coxwell Avenue all the way to Danforth Avenue. But he had more freedom to develop them as he wished without the constraints of City Bylaws since Duggan’s holdings were in the Township of York (East).

In 1896 May 7 Cranford Craven died. He was very probably the source of the name “Craven Road”, although it could also have been named for a “Craven Road” in London, England.

The 1903 Goad’s Atlas shows a right of way across the Ashbridges Estate and E. H. Duggan’s five lots. Gerrard Street has been opened a short distance east of Greenwood (200 feet to the City limit) and a short distance west of a new lane running north south off of Queen. This new lane or road opened along the edge of the old farm fields to Gerrard. This would become Reid and then renamed as Rhodes Avenue.

They Were All As Happy As Clams

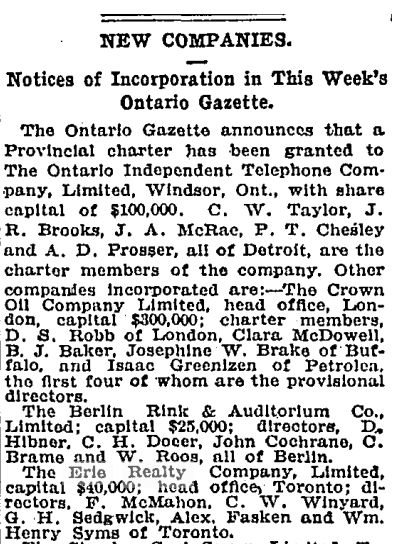

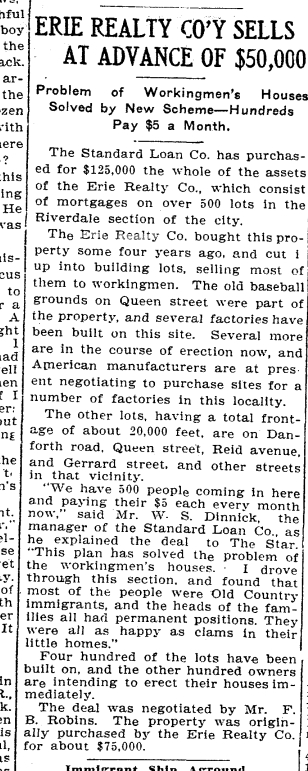

In 1904 the Erie Realty Company, Limited, was incorporated with capital of $40,000; Head office, Toronto and Directors, F. McMahon, C. W. Winyard, G. H. Sedgwick, Alex. Fasken and Wm. Henry Syms of Toronto. Around this time E. H. Duggan sold his holdings for $75,000 to the new Erie Realty Company.

In 1905 the Erie Realty Company launched what was their first big project, the Sunlight Park industrial subdivision between Eastern Avenue and Queen Street. They wanted a rail siding and fought for it against the objections of the Sunlight Soap Company. They won the siding into their property in 1906. Their next big project was the Reid Avenue and Erie Terrace subdivision which went on the market in 1906.

Toronto Star, May 29, 1906

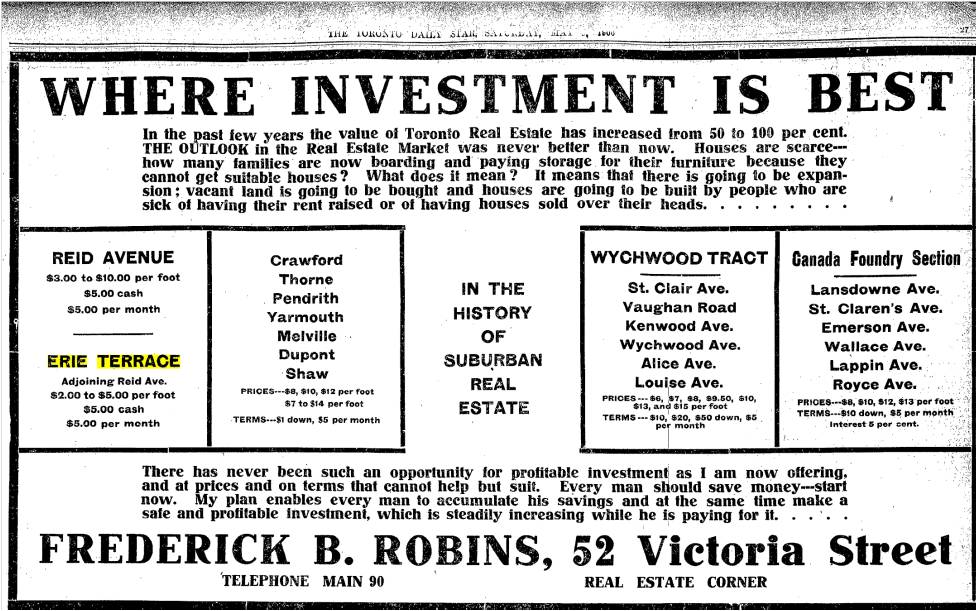

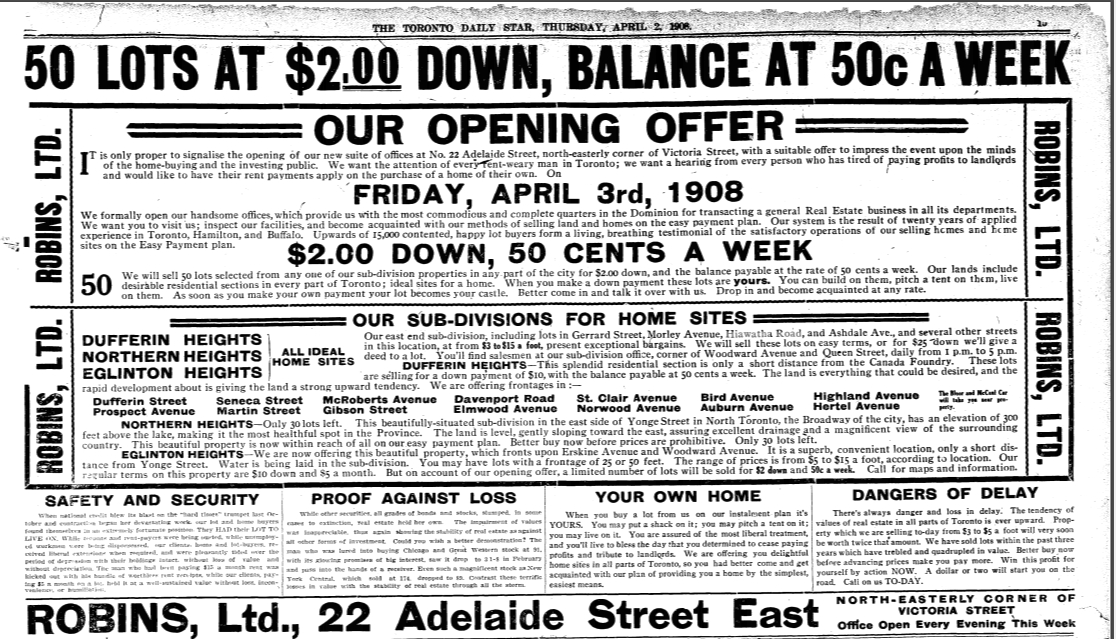

Frederick B. Robins and his real estate company acted as agent in the sales. Their target market in 1906 was not potential home owners but smaller investors. His advertisement of May 5, 1906 states “Where Investment is Best”

WHERE INVESTMENT IS BEST

In the past few years the value of Toronto Real Estate has increased from 50 to 100 per cent. THE OUTLOOK in the Real Estate Market was never better than now. Houses are scarce – how many families are now boarding and paying storage for their furniture because they cannot get suitable houses? What does it mean? It means that there is going to be expansion; vacant land is going to be bought and houses are going to be built by people who are sick of having their rent raised or of having houses sold over their heads. (Toronto Star, May 5, 1906)

Land on Reid Avenue was sold for $3.00 to $10.00 per foot of frontage with $5.00 cash down and a mortgage offered at $5.00 per month. The interest rate is not mentioned, but was probably around six per cent. Most mortgages at the time had a term of only three to five years.

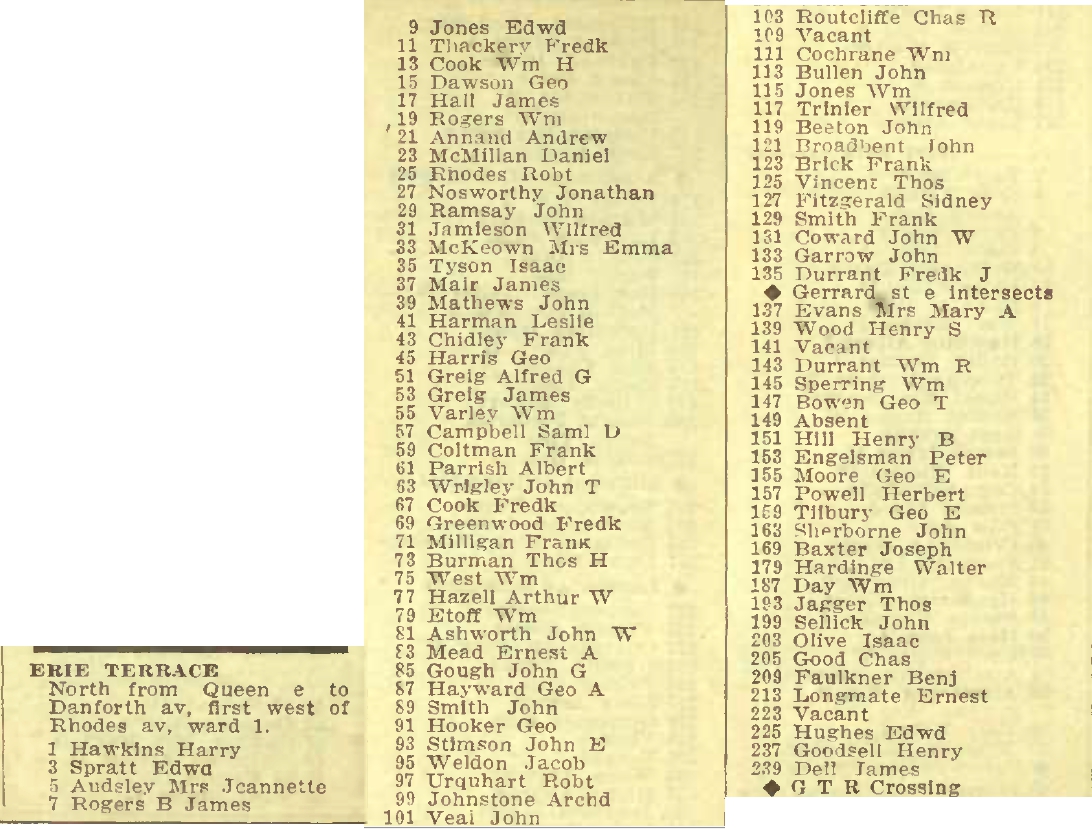

Erie Terrace was only 18 feet wide, the width of the original cart way, not the full 33-feet of a country road. At about the same time or a little later, Jesse Ashbridge and his brother Wellington Ashbridge decided to sell most of the estate that been in their family since the 1790s. While real estate agents handled much of the business, the Ashbridges brothers kept a close watch on developments. Jesse Ashbridge opened up Ashdale Avenue in April 1906 and named it after the valley or “dale” and his own last name.

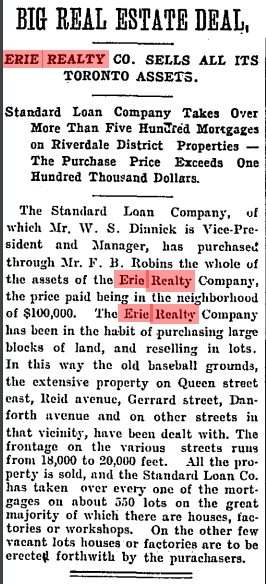

In August, 1910, the Standard Loan Company (later becoming the Standard Loan and Mortgage Corporation) purchased Erie Realty Company. W. S. Dinnick was Vice President and General Manager of the new bigger development company.

Globe, Aug. 10, 1906

The Erie Realty Company has been in the habit of purchasing large blocks of land, and reselling in lots. In this way the old baseball grounds, the extensive property on Queen street east, Reid avenue, Gerrard street, Danforth avenue and on other streets in that vicinity have been dealt with. The frontage on the various streets runs from 18,000 to 20,000 feet. All the property is sold, and the Standard Loan Co. has taken over every one of the mortgages… (Globe, Aug. 10, 1906)

The developers felt that they were meeting a real social need at a time of an acute housing crisis:

“We have 500 people coming in here and paying their $5 each every month now,” said Mr. W. S. Dinnick, the manager of the Standard Loan Co., as he explained the deal to The Star. “This plan has solved the problem of the workingmen’s houses. I drove through this section, and found that most of the people were Old Country immigrants, and the heads of the families all had permanent positions. They were all as happy as clams in their little homes.”

Four hundred of the lots have been built on, and the other hundred owners are intending to erect their houses immediately.

The deal was negotiated by Mr. F. B. Robins. The property was originally purchased by the Erie Realty Co. for about $75,000. (Toronto Star, Aug. 10, 1906)

Robins was also involved in The Dovercourt Land Company, in which E. H. Duggan had interests. Eventually both The Dovercourt Land Company and Erie Realty Company would be subsidiaries of the Standard Reliance Mortgage Corporation. Frederick. B. Robins acted as the real estate agent for both the Ashbridges and the Erie Land Company. Robins was instrumental in selling lots and houses from Greenwood to Coxwell and from Queen Street to Danforth Avenue.

In this way Erie Terrace and Rhodes Avenue was intentionally developed as a “Shacktown”, outside of Toronto, in 1906, at virtually the same time as the Ashbridge’s Estate further west was subdivided for housing. Shacktown also developed on the newly-opened Ashbridge’s Estate subdivision to the west, but not to the density of Erie Terrace. Now Craven Road, it has many tiny owner-built houses, most of them the original shacks put up by the “Shackers”. The developers maximized their profits by subdividing Erie Terrace into as many small lots (some only 10 feet wide) as possible and selling them quickly to poor people desperate for housing even though that housing came with none of the amenities necessary to support a densely populated subdivision. The development offered no water mains, no sewers or drains, no paved roads or sidewalks and almost non-existent police or fire services. It appeared as if the Township was happy to collect the taxes but reluctant to provide any services beyond a four-roomed school.

However, in York Township taxes were low and the Township Bylaws seemed non-existent. Even the very poor could afford to buy lots at mortgages that cost less than monthly rent.

Ashdale Avenue was subdivided into larger lots and the Ashbridge brothers had a different strategy. They sold larger lots at a higher price to slightly more affluent buyers. Those larger lots backed onto the west side of Erie Terrace. How the Jesse and Wellington Ashbridge, brothers, controlled the Sam Hill Estate and how they were involved with the Erie Realty Company requires further investigation, but it is clear that the brothers acted as trustees of the Samuel Hill Estate, on behalf of their close relative, Sam Hill’s heir, William Hill.

Shacktown

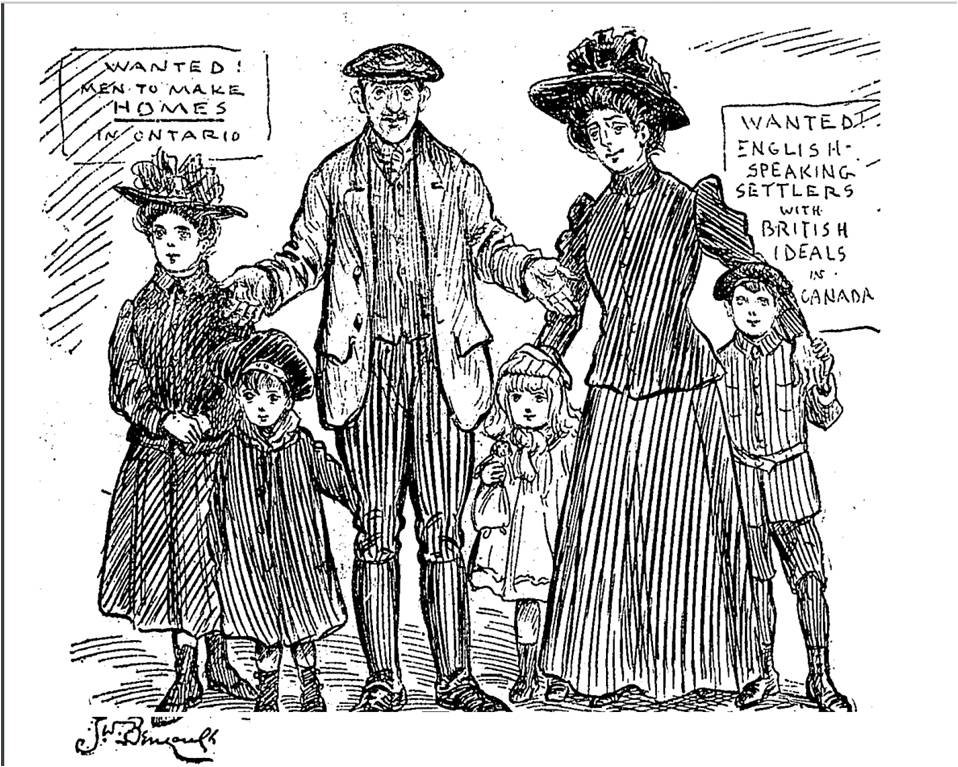

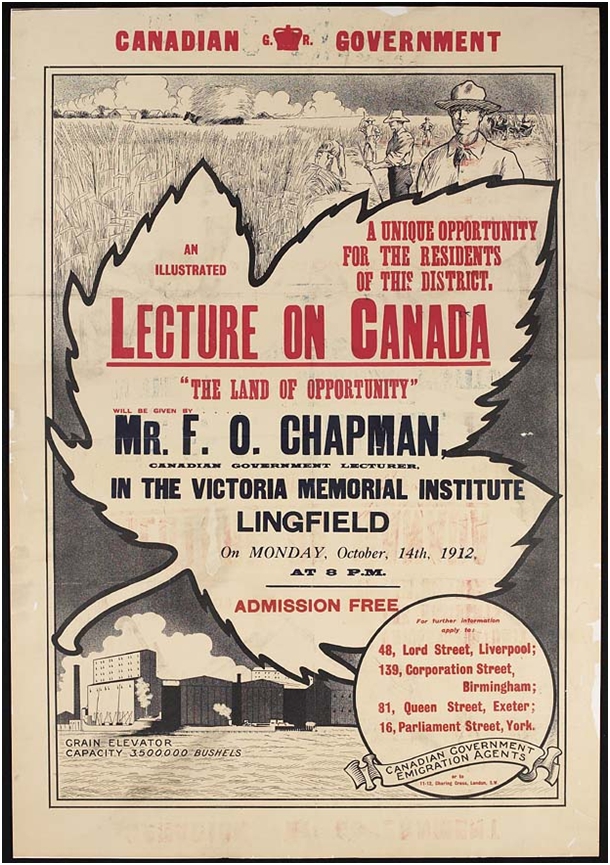

Eight Shacktowns, like that on Erie Terrace, developed just outside the Toronto’s limits where City of Toronto, regulations did not reach. They formed a horseshoe of poverty just outside the City limits. Erie Terrace became a linear slum perched in sand on the edge of a deep a ravine called the Ashdale Ravine. Shacktowns were full of young couples, new immigrants from Britain. In many cases they were very poor. Their ship passage to Canada was subsidized by “the British Bonus”. York Township, just outside Toronto provided cheap building lots where they could build their own homes from whatever they could scavenge or scourge:

This shacktown is that part of the town where the building of shacks and shanty residences goes on in a mushroom-like style, and is where the latest arrivals of the English immigrants are striving to get a habitation for the winter. (Toronto Star, Nov. 1, 1907)

For many on Erie Terrace their first Canadian summers, those of 1906 and 1907, were the best of their lives, and the first winter was mild. Mostly young couples with children, they quickly got to know their neighbours. They had picnics; formed churches; enjoyed playing sports (especially soccer); and revelled in the woods and fresh air here. They co-operated to build each other’s houses in house-building bees. Many were tradesmen such as carpenters, plumbers and electricians, with the skills to do the work.

Thanksgiving Day was the busiest of the year in Shacktown…the outer fringe of the east and the northwest district. (Globe, Nov. 1, 1907)

There was one last holiday before winter to get work together to put up each other’s homes.

Brick, roughcast, clapboard, plain board, cement blocks, shingles, tar-paper fronts and roofs, glorified packing cases, are all to be seen in the streets of Shacktown. The work seems to be done largely on holidays, on the “bee” principle. A group of bricklayers can be seen here and there rushing up a brick front, while around frame structures that rise while you wait carpenters are swarming—quite properly, if it is a bee.

…The settlement is the newly-arrived Britishers’ answer to the demand for $18 and $10 a month for working-class houses. With a couple of thousand feet of lumber, two or three lengths of stove-pipe and the help of his chums on such a holiday as yesterday the shacker becomes his own landlord. (Globe, Nov. 1, 1907)

But storms lay ahead, both literally and figuratively. In October 1907, a financial crisis struck as stock market players tried to corner the market on a copper company’s stock. When nervous people drew out all their savings, banks began to collapse. The economy nose dived and soon the Shackers would find themselves “last hired, first fired”. Whiles the Shackers had high hopes for themselves, their children, their neighbours and their tarpaper houses, most would soon become unemployed, without food, fuel and proper clothes for the first hard Canadian winter. The British immigrants began to suffer intensely.Through no fault of their own the Shackers were unemployed and broke. Unfamiliar with our weather, they began to freeze in unheated shacks as a fierce Canadian winter began.

Some clearly saw the suffering that lay ahead and wanted out. A Toronto Star classified ad of Nov. 2, 1907, indicates this:

FOR exchange, 100 feet, on Armadale avenue, 50 feet on Erie terrace , for house not over $2,000, balance cash, 42 Blake street.

Small contractors and builders were in trouble as well. Most houses were either built by the Shackers themselves or by builders who put up houses cheaply using kits or plans. They usually only bought five to six lots and put up a hand full of houses at a time. Prices fell lower as builders tried to sell in December.

Some of the smaller investors who had hoped to make a quick buck on their half dozen lots, even offered free lumber:

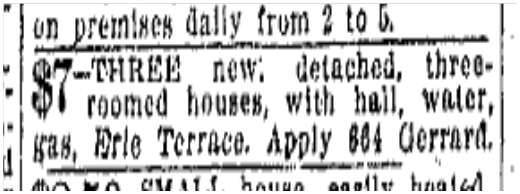

$10 A FOOT – Erie Terrace, 100 feet north of Gerrard street cars, no money down, lumber supplied to build. Davis, 75 Adelaide east. (Toronto Star, Dec. 21, 1907)

But by that time, the worst winter in living memory swallowed up the wonderful summers of 1907. In late January, 1908, the Globe received a tip that people were starving. The Globe described Shacktown as having no government, no charities, men out of work, women worn out. Reporters found families without fuel or food, children with frost bite, and people critically ill without a doctor, medicine or even blankets. They launched the Shacktown Relief Fund on January 27, 1908. In the first day of the Globe’s appeal over $1,100 was sent. (Most factory male workers bought home about $7 a week.)

One reporter describes the desolation:

The sound of little children crying was yet in the wind that whimpers and blow over the land of tar-paper homes when The Globe reporter visited it last night. (Globe, Feb. 1, 1908)

The Globe’s campaign was successful from its inception. Donations began pouring in from across the Province within a week of the Fund’s birth. The Globe promised that, “None will go without food in Shacktown District”. On its first day the fund received $1,138.

St. George’s Hall was the headquarters for the Shacktown Relief Fund where donations were received, sorted and distributed. The depot acted like “a wholesale dry goods establishment” with clothing pouring in and volunteers sorting the food and clothing. Warm winter clothes were as welcome as cash. The early courier companies (called “Express Companies”) offered to pick up and deliver donations from across Canada “for the purpose of affording relief to the immigrants.” All someone had to do was mark on the parcel “Shacktown Relief Fund” and call either Canadian or Dominion Express Companies and it would be delivered to Toronto and quickly distributed to where, “The cry is for more”. (Globe, Feb. 6, 1908)

Shacktown that winter shocked even experienced social workers (known as “relief workers” then). It changed how they thought about people in need. People were quietly keeping “the stiff upper lip” the British were known for and suffering intensely behind their tarpaper walls.

A clergyman [Rev. Robert Gay, St. Monica’s Anglican Church] in an east end division, who is an untiring worker in the campaign of relief, told The Globe yesterday that he once thought he had had all the experiences that could come to anyone engaged in that kind of work. His conclusion had, he said, been rudely shattered when on the previous evening he found five families of his own parish who he believed to be independent of any charity in dire distress. The thought of taking relief to them was almost embarrassing to him, and it was only with the greatest difficulty that he could induce them to tell their circumstances. In two cases his offer of orders on the grocer was refused. “What,” exclaimed one woman in sobs, “What would ma people in Scotlan’ think if they heard o’ this?”

The Poor Divide Up With the Poor.

Rev. Robert Gay, who is in charge of district 7, in the eastern territory, writes: — “I came across a case recently of a man and his wife who had scarcely any food and no money. The man was out of work, and the wife’s efforts to get work were of no avail. They were hard pressed, but were not so poor that they could not help those worse off than themselves. They took in two friends, a married couple from the city, who had been turned out by their landlord for failure to pay the rent, and together the household had been putting up a brave fight. It was a case of the poor helping the poor. (Globe, Feb. 7, 1908)

The children of Shacktown risked life and limb to obtain fuel for their stoves. The kitchen stove was usually the only source of heat in the tarpaper shacks. They scavenged along the railway tracks where bits of coal fell off the trains. The fireman shovelled coal into the furnace on the locomotive, creating the stem that powered the engine. Sometimes unburned chunks flew off, but half-burned pieces called “clinkers” also flew through the air. The first children on the scene when a train passed were the most likely to get some free fuel. This created a rush of boys and girls along the tracks north of Erie Terrace and Rhodes Avenue, a dangerous situation. A number of children met gruesome deaths, mangled by trains.

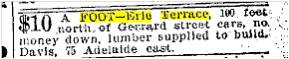

Robert Gay, the minister of St. Monica’s Church on Gerrard at Ashdale, was deeply distressed by the condition of his parishioners. This Anglican mission church sat where the Toronto Public Library’s Gerrard-Ashdale Branch is today and most of the people in that Shacktown were Anglican though there were a number of Presbyterian Scots and Irish who attended Rhodes Avenue Presbyterian Church. As well there were a few Methodists who went down Morley Avenue (Woodfield Road) to the old Leslieville Methodist Church at Vancouver and Queen. Robert Gay described his experience:

“I visited a home yesterday and found a man with his wife and eight children, living on what the oldest girl, aged eighteen years, could earn. The husband was out of work, as was also the oldest boy, a lad of sixteen years. I had great difficulty in eliciting any information from the family. I found them lacking bed clothing, food and fuel. So cold had the house been that there had been ice on the walls of the bedrooms. With the assistance of a neighbor we moved the solitary stove, so that its heat would be evenly distributed. Stovepipes were bought and blankets and food supplied. The coal was delivered later.” (Globe, Feb. 7, 1908)

The Globe visited another Coxwell-Gerrard area house where the father of the family had been out of work for 11 weeks. There four little kids in that family. The mother was pregnant with one more and there was no food or fuel in the house. The Relief Fund supplied food and coal, as well as calling in a doctor and nurse for the expectant mother.

By mid February, 1908, Shacktown or “the Tar Paper Region” was beginning to feel the impact of the Shacktown Relief Fund. Contributions of both goods and cash were flowing in. With just under a thousand dollars a day coming in, the cash fund was at over $13,000.00. The welfare state as we know it today simply did not exist. Thousands of families were dependent entirely on the Shacktown Relief Fund for food, clothing and fuel.

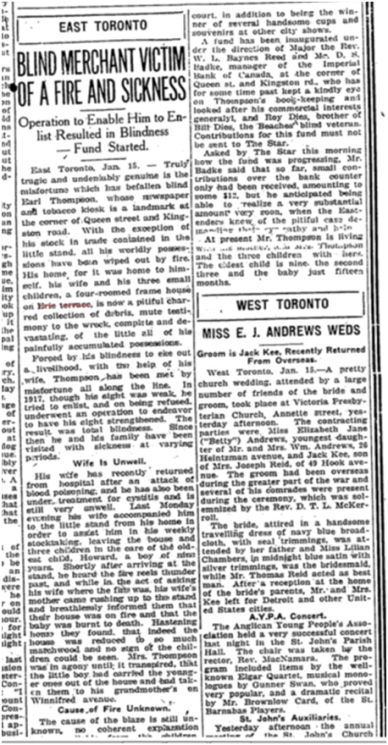

Shackers like those on Erie Terrace were vulnerable not only to the cold, but to fire. This house on Reid Avenue (now Rhodes Avenue) illustrates the danger of living in Shacktown where there was no fire department to put fires out. Fire fighters from the City of Toronto would, if they were available, come out to fight Shacktown fires, but they were not always free to do so. The Shacktown streets had no water mains and no water hydrants. Water to fight the fire had to come from the small creeks such as Ashbridge’s Creek and ponds in brickyards.

Most houses were not as well constructed and most Shackers had no fire insurance.

BLAZE ATE UP THE INTERIOR OF HOUSE

Fierce Fire in Reid Avenue – Woman Outside When Fire Started, Couldn’t Get In.

A fierce blaze, which wiped out the contents and badly damaged the home of Robert Kenmare, 2 Reid avenue, broke out at 10.20 this morning. It burned for less than an hour, and when the flames were extinguished the walls, floors, ceilings, and furnishings were about burned away.

The house is a four-roomed, two-storey one, of frame, built by Mr. Kenmare during the year. When the fire broke out, Mrs. Kenmare was hanging clothes in the yard, and although the smoke attracter her attention at once, she found that the fire was too hot to allow her to enter her home.

A coal stove, placed temporarily beneath a staircase in the hall, on the first floor, is believed to have overheated.

Mr. Kenmare, who is employed as an engineer by the Quaker Candy company, Jarvis street, was notified by telephone.

“Fortunately, both children were at school,” he said, in discussing the occurrence, with The Star. “I intended to build an addition in the spring, but I don’t know how badly the joists are burned.” (Toronto Star, Feb. 26, 1908)

By mid-February 1908, the Relief Fund was meeting Shacktown’s basic needs. Spring would, bring not only flowers but work. The economy recovered as investors intervened to stabilize the stock market and banks. While jobs were one solution to the Shackers’ problems; annexation was another.

The people of Erie Terrace and the neighbouring Shacktown began to ask to be annexed to the City of Toronto. They stood to gain social welfare benefits, meagre as they were. In the Township of York, they were without water mains, sanitary sewers, decent fire and police services and good roads. While technically they were not in Toronto, culturally they were city folk, far more “of Toronto” than rural-dominated York Township. They overwhelming supported amalgamation with the City of Toronto despite the higher taxes entailed. Shacktown would get water, sewers, fire, police and paved streets if they joined Toronto. They voted to join the City.

In the spring of 1908 the economy bounced back quickly and with it came jobs. The Shackers stayed and many more joined them, enticed by Robins ads like the one below. Robins was acting on the Ashbridge brothers’ behalf, selling lots, but also giving the credit to buy those lots, with mortgages held by the Ashbridges, at least initially.

Toronto Star, April 2, 1908

Our Sub-Divisions For Home Sites.

Our east end sub-division, including lots in Gerrard Street, Morley Avenue, Hiawatha Road, and Ashdale Ave., and several other streets in this location, at from $3 to $15 a foot, present exceptional bargains. We will sell the lots on easy terms, or for $15 down we’ll give a deed to a lot. You will find salesman at our sub-division office, corner of Woodward Avenue and Queen Street, daily from 1 p.m. to 5p.m.

Credit was cheap and the immigrants had little choice. There simply wasn’t enough housing available. Their solution to the housing shortage was to buy cheap in Shacktown, on streets like Ashdale, and build their own.

SAFETY AND SECURITY

When national credit blew its blast on the “hard times” trumpet last October and contraction began her devastating work, our lot and home buyers found themselves in an extremely fortunate position. They HAD their LOT TO LIVE ON, While tenants and rent-payers were being ousted, while unemployed workmen were being dispossessed, our clients, home and lot-buyers, received liberal extensions when required, and were pleasantly tided over the period of depression with their holdings intact, without loss of value and without depreciation. The man who had been paying $16 a month rent was kicked out with his bundle of worthless rent receipts, while our clients, paying $6 a month on a lot, held it at a well-sustained value without loss, inconvenience or humiliation.

During the hard winter of 1907-08, the Ashbridges did not foreclose on people who could pay, hoping that when the economy picked up they would get their money. So while others were being evicted from their rented houses and apartments downtown, the Shackers were still housed, however inadequately.

YOUR OWN HOME

When you buy a lot from us on our instalment plan it’s YOURS. You may put a shack on it; you may pitch a tent on it; you may live on it. You are assured of the most liberal treatment, and you’ll live to bless the day that you determined to cease paying profits and tributes to landlords. We are offering you delightful home sites in all parts of Toronto, so you had better come and get acquainted with our plan of providing you a home by the simplest, easiest means.

Robins, Ltd. 22 Adelaide Street East North-easterly corner of Victoria Street. Office Open Every Evening This Week.

Shackers found jobs picking fruit or berries. Many men travelled to Western Canada to work in the harvest. With the winter of 1908 inevitably drawing nearer, there was concern about another crisis in Shacktown. Officials from the major charities and City of Toronto Controllers and Aldermen made up the Special Civic Committee for the Relief of the Unemployed. In the summer of 1908, “the worst was feared” by some. However others were less concerned because the summer of 1908 had produced a bountiful harvest and factory work had picked up.

On February 27, 1909, the Globe reported on the final audit of the account of the Relief Fund. Almost $19,000 had been donated, not including donations in kind. The Globe congratulated the Fund’s workers for creating an effective relief system that avoided welfare fraud while delivering relief quietly and quickly at minimal cost. The Committee which had come together “on a few days’ notice” could now wind down. After the Shacktown fund was closed, money raised in fundraisers for Shacktown was donated to other charities such as the Children’s Aid Society. (Globe, Feb. 27, 1909)

The Shackers Stand Together and Demand Better Service From the City

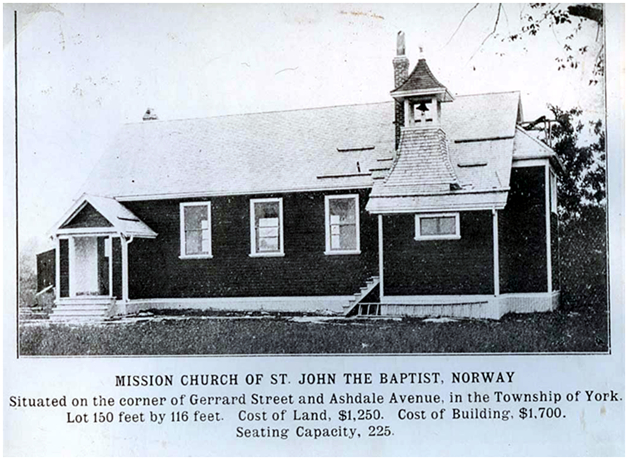

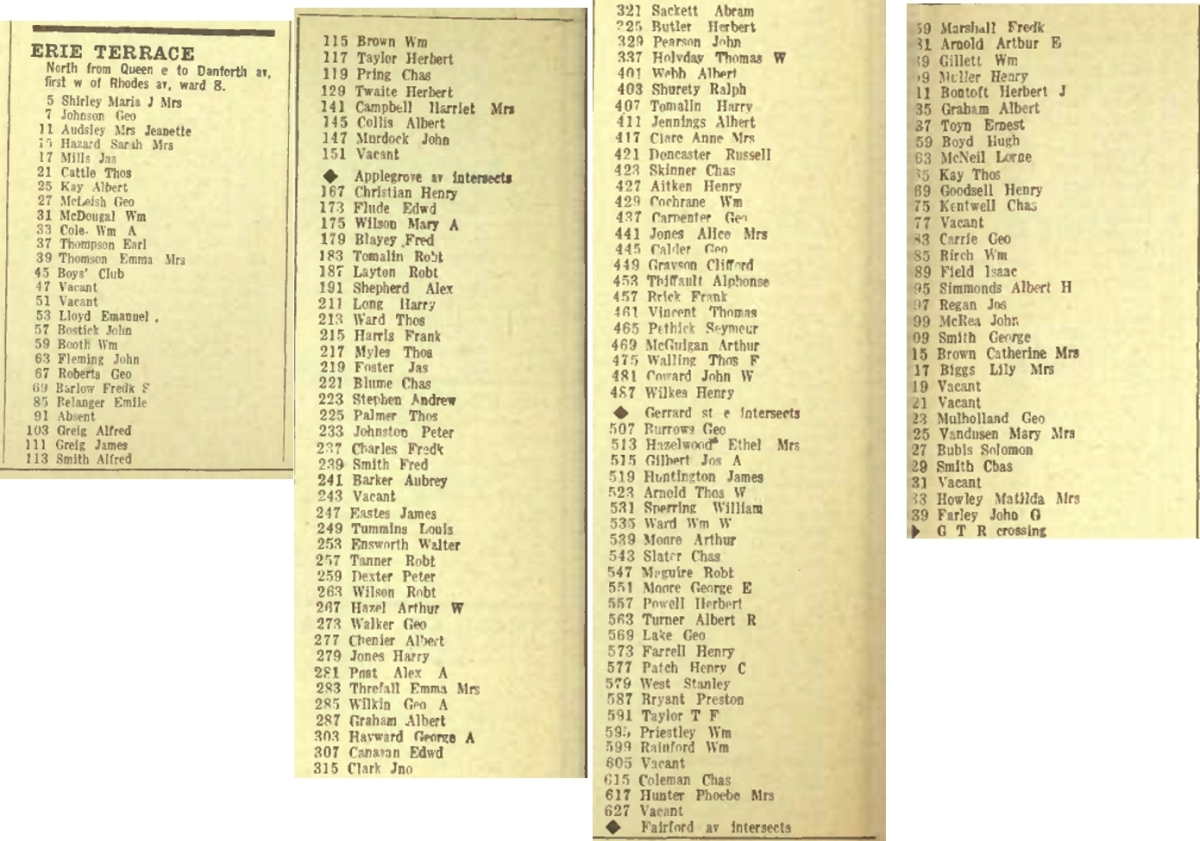

In 1909 Erie Terrace and the Shacktown around it became part of Toronto. Might’s Directory of 1909 reflects the growth in 1908. Houses began to go up again as sales picked up.

$7-THREE new; detached three-roomed houses, with hall, water, gas, Erie Terrace. Apply 664 Gerrard. (Toronto Star, Dec. 17, 1910)

$800 – COSY three-roomed cottage in Erie terrace, just north of Gerrard street, $50 down, balance like rent. Interest only 6 per cent, North 71 Adelaide. (Toronto Star, June 8, 1911)

Life went on. The circus came to town and little Tommy Beeton, of 119 Erie Terrace, fell out of a tree where he could see the goings-on behind the canvas circus fence. He landed on his head but, after a night in the hospital, seemed just fine. Spot, the fox terrier, of 1 Erie Terrace was lost somewhere near the Steele Briggs greenhouses and gardens at Kent and Queen.

LOST – Fox terrier, on Sunday morning, white with small black spots, dark ears, answers to name of Spot; tag number 1908, is a pet. Liberal reward No. 1 Erie Terrace, near Steele Briggs flower gardens, Queen east, phone Beach 596. (Toronto Star, Oct. 23, 1911)

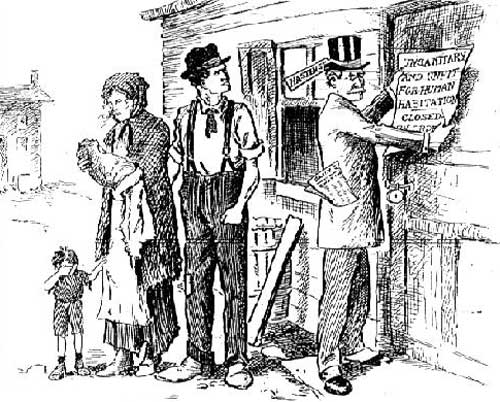

The Erie Land Company and made fortunes selling lots while the Standard Loan Company collected the mortgage money. This company, like some others, did not generally foreclose on mortgages during the crisis of 1907-08, hoping to get it’s money when the economy recovered. It did. All seemed well in Shacktown, but when the City of Toronto, pushed by Chief Officer Dr. Charles Hastings, raised its standards for housing, many were evicted. Medical Officer of Health, Dr. Charles Hastings hated typhoid fever (a waterborne bacterial disease): it killed his little daughter. Pushed by Hastings, the City of Toronto passed a By-law requiring all houses in the newly annexed areas to have a flush toilet, a wash basin, a connection to City sewers and piped-in City water. Erie Terrace residents protested against being charged for sewage connections. They had no choice but to comply or leave. The Public Health Department closed their homes as unfit for human habitation if they failed to puts in “the modern conveniences”.

Some fought back. Frank Magauran appeared before the City Committee to protest against being charged $20.92 for sewage connection for his house on Erie Terrace. The work cost $11.89, but the City of Toronto charged everyone a flat fee of $18, plus a $2 connection charge, and 92 cents for overhead charges. Magauran claimed he should only pay $11.89, the actual cost. He lost. (Globe, Oct. 23, 1911)

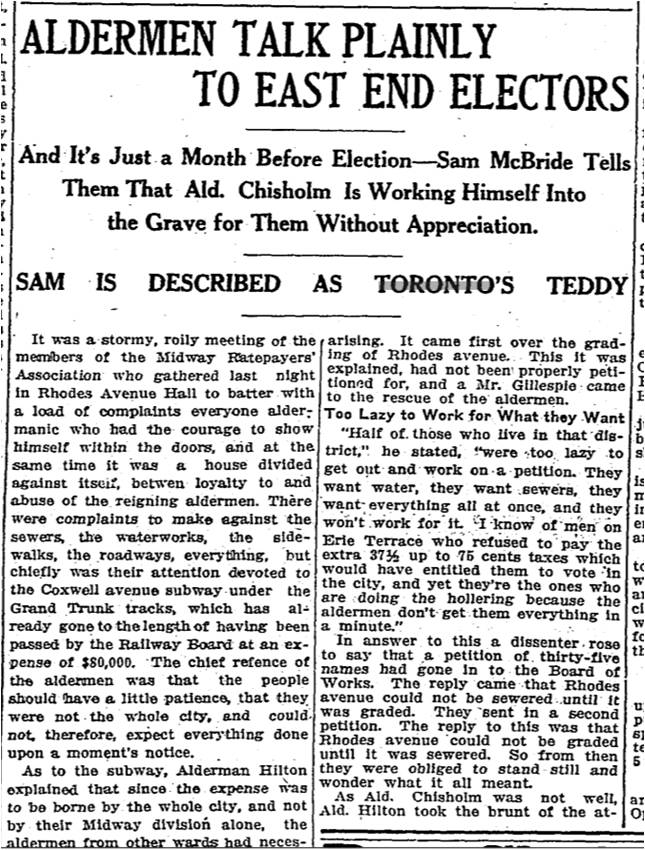

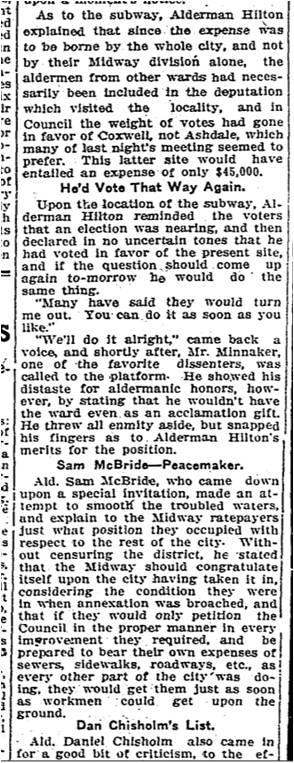

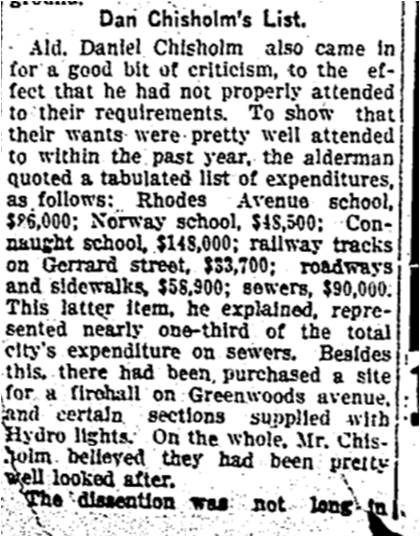

The immigrants brought with them great dreams and great expectations, but, initially at least, their hopes were thwarted by the lack of amenities and services. These were services that these British urbanites took for granted and hoped to get quickly now that Erie Terrace and other streets were officially part of Toronto. The prolonged delay in getting basic services came as quite a shock. They demanded change as they met with their elected representatives in meeting after meeting. The records of one meeting in particular make clear their frustration. On December 2, 1911, the members of the Midway Ratepayers’ Association met with their aldermen in the Orange Hall on Rhodes Avenue.

It was a stormy, roily meeting of the members of the Midway Ratepayers’ Association who gathered last night in Rhodes Avenue Hall to batter with a load of complaints everyone aldermanic who had the courage to show himself within the doors, and at the same time it was a house divided against itself, between loyalty to and abuse of the reigning aldermen.” …”Half of those who live in that district’ he [local resident Mr. Gillespie] stated, “were too lazy to get out and work on a petition. They want water they want sewers, they want everything all at once, and they won’t work for it. I know of men on Erie Terrace who refused to pay the extra 37 ½ up to 75 cents taxes which would have entitled them to vote in the city, and yet they’re the ones who are doing the hollering because the aldermen don’t get them everything in a minute. (Toronto Star, Dec. 2, 1911)

They wanted a subway built under the Grand Trunk Railway to improved road access from the neighbourhood to Danforth Avenue and Queen Street East. They wanted a walkway build under the railway track so that children could get safely from the streets north of the rail line to Roden School.

Alderman Sam McBride, who came down upon a special invitation, made an attempt to smooth the troubled waters, and explain to the Midway ratepayers just what position they occupied with respect to the rest of the city. Without censuring the district, he stated that the Midway should congratulate itself upon the city having taken it in considering the condition they were in when annexation was broached… (Toronto Star, Dec. 2, 1911)

City politicians were not about to put up with ingratitude from Shacktown.

Alderman Chisholm responded: “You came here because this land was cheap. If you expect the city Council to put in waters, sewers, etc., and make your land valuable in a minute, you are mistaken, it can’t be done. Erie Terrace wants the city to bear the expense of its widening. Other streets don’t get such concessions, and as for your aldermen, we have far, far exceeded any promises we ever made to you.” (Toronto Star, Dec. 2, 1911)

In essence the politicians told the disgruntled ratepayers that they should be happy that the City of Toronto took the neighbourhood in at all given the bad shape it was end. Being told that they should be grateful for their lot and not complain did not go over well. Erie Terrace was getting a reputation like Regent Park or Jane Finch has today. The poor, apparently, can only be seen as deserving for a limited period of time. Pity quickly slides over into disdain and gratitude at hand-outs becomes anger at dispossession. How quickly brave and courageous Britishers could become good-for-nothing, dirty immigrants with juvenile delinquents for children – at least in the minds of money! The very lay-out of Erie Terrace was blamed for the poverty there not the fact that it was laid out for people who were poor.

The Great War: Father of The Fence

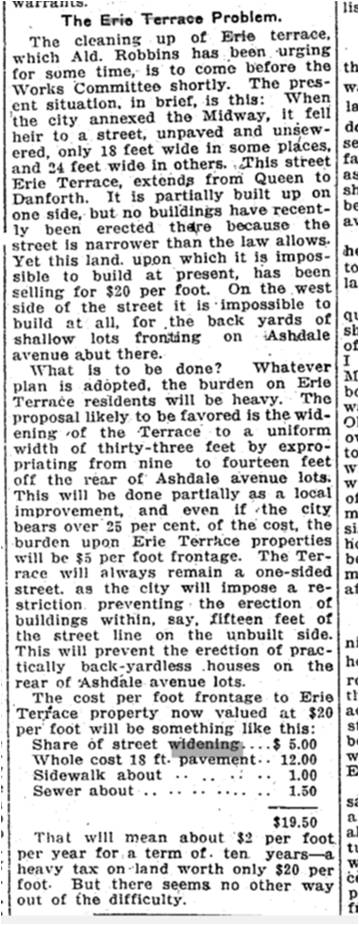

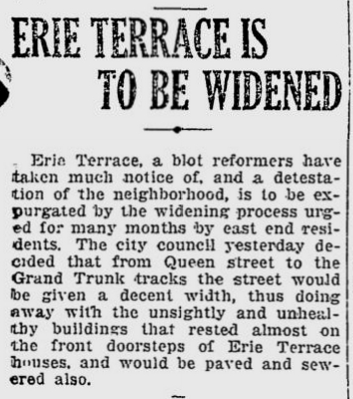

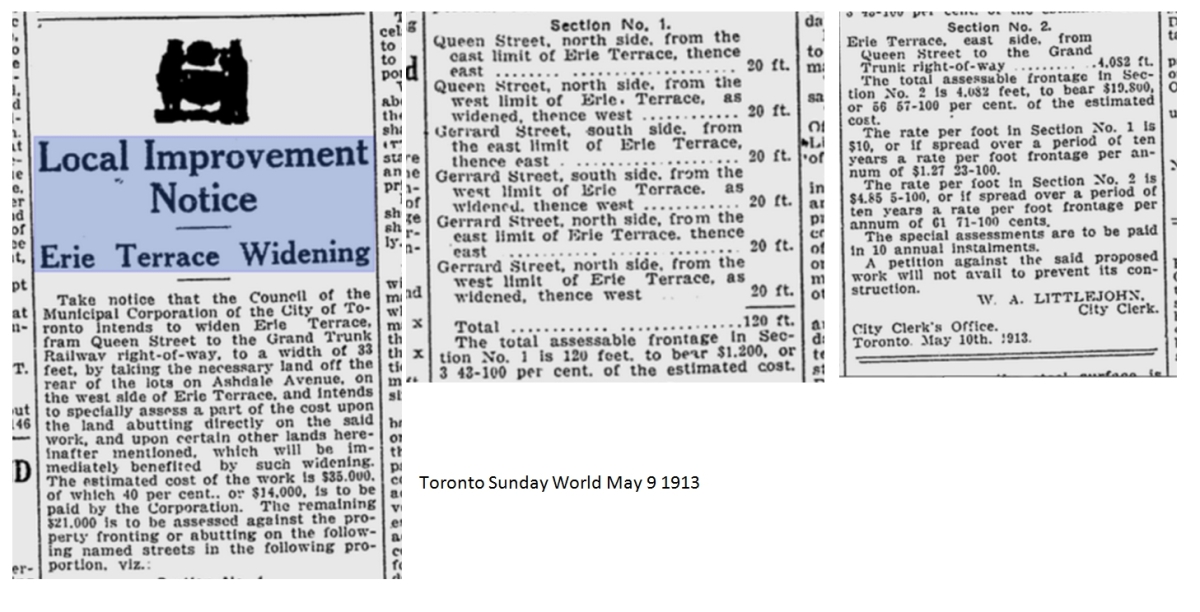

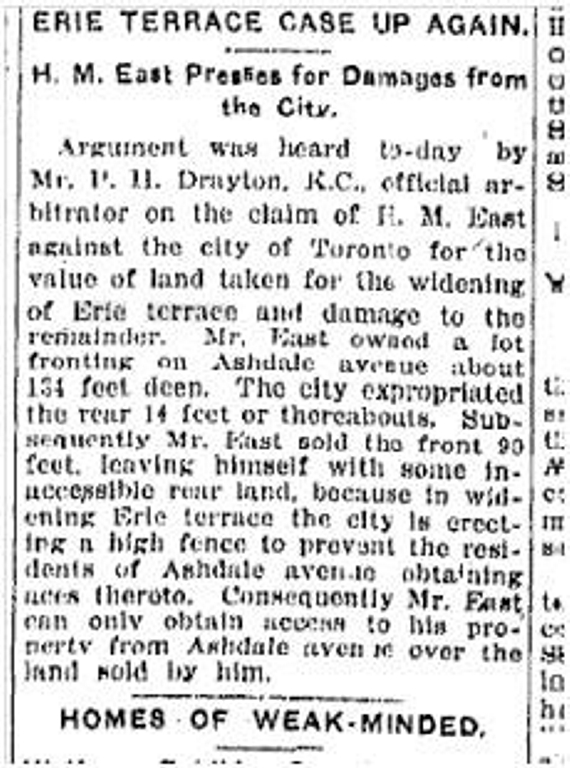

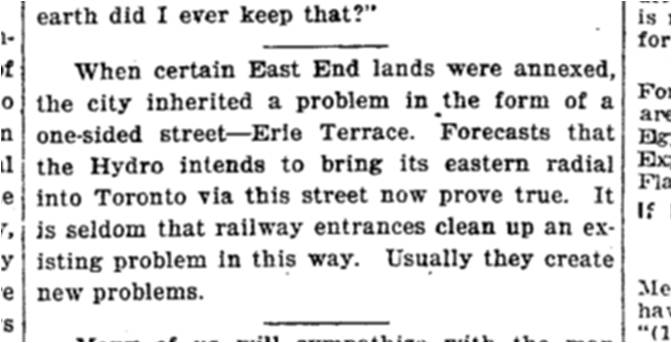

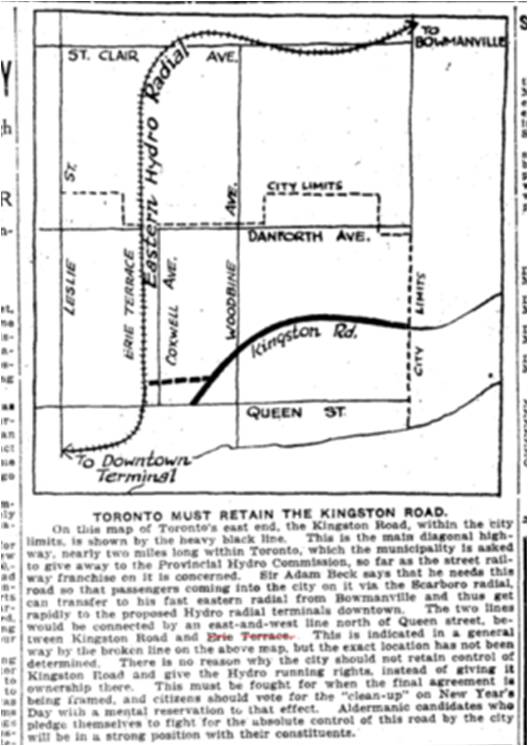

In December, 1911 the Board of Control for the City of Toronto authorized the widening of Erie terrace. This would cost $6,000 and the city would pay $2,400 of that but the residents of the street were expected to pay $3,600: money they didn’t have. (Toronto Star, Dec. 16, 1911) They may have authorized it, but no one on Erie Terrace could pay for it. The Midway Ratepayers’ Association tried to push both residents and the City to improve conditions on Erie Terrace (Globe, Jan. 6, 1912), but the problems seemed insoluble.

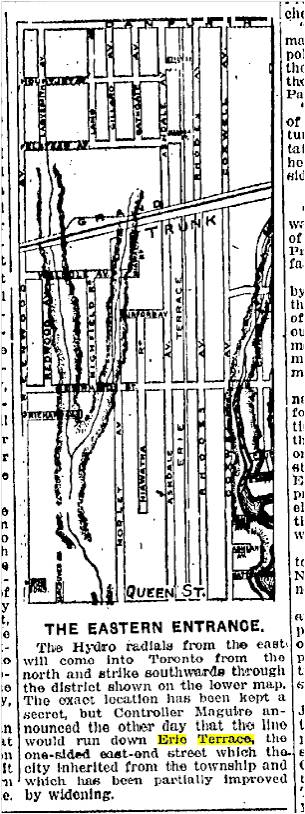

The Works Department has a number of vexatious street problems on hand, and the committee made personal investigation into some of these yesterday. One is on Erie Terrace in the Midway. It runs north from Queen street to Danforth avenue and the width varies from 15 to 22 feet. There are small frame houses along one side and on the other are the backyards of houses which front on an adjoining street. It is proposed to add about ten feet to the width of Erie Terrace, taking the land from these yards.

But what then? Who will pay? The houses now built on the Terrace will have to pay their share, the city will have to pay its share, but what about the share which would ordinarily be paid by the properties on the opposite side of the street? The people whose back yards are taken get no benefit from the street improvement, for their residences front on another thoroughfare. Erie Terrace is their back lane and they don’t care whether it is ten feet wide or thirty-five. There is no room to build houses on both sides of the Terrace and the city will have to find some way out of the difficulty. (Toronto Star, February 1, 1912)

George R. Geary, Mayor of Toronto from 1910 to 1912, even suggested that the City buy up Erie Terrace, presumably to clear it of houses and residents. (Toronto Star, Sept. 25, 1912) This strange little laneway with houses on one side only and backyards on the other bewildered City politicians and bureaucrats:

The City Fathers have decided to put Erie Terrace in better shape, but the problem which confronts them on that street is difficult of solution. It came into the city with the “Midway” district, and has puzzled municipal authorities ever since. Although it extends from Queen street to Danforth avenue, and is thickly built up on from Queen to Gerrard, it is only from 18 to 23 feet side, and the houses, mostly wooden shacks, are built on only one side of it. On the other side are backyards of properties fronting on Ashdale avenue. A two-plank sidewalk was laid on Erie Terrace, but the road is so bad that wagons have been driven with two wheels on the walk, which has become badly smashed in consequence. There is no sewer. It is thought inadvisable to put a pavement on a street only 20 feet wide, yet if it were widened, the residents along the one side would have to pay for the widening and for the whole of the pavement. The other side cannot be built upon, as there are nothing but backyards on it, and 20 feet taken off these would not leave room for houses. What will the city do with Erie terrace, which threatens to become a permanently undesirable street a mile and a half long? (Toronto Star, Oct. 2, 1912)

Meanwhile more houses were going up as the first water and gas mains were laid south of Gerrard:

$200 CASH, new cottage, water, gas, south Gerrard, Erie Terrace, balance eight hundred, ten monthly. One hundred cash, cottage, three nice rooms and hall; houses rented ten dollars monthly. 168 Morley. (Toronto Star, Aug. 28, 1912)

The Province, meanwhile, had passed an Act to prevent more Erie Terraces:

The Act passed last year restricting the narrowness of streets within five miles of cities was enacted with a view to protecting the cities against conditions which encourage slums when additional territory is annexed. Thus, if streets 33 feet wide are permitted in the county, they become eyesores when the district in which they exist is taken into the city and becomes more thickly populated. Toronto has already problems of this type on hand. When the city annexed the Midway district, Erie Terrace was brought within the limits. And Erie terrace is in places only 18 feet side. It has houses on one side and back yards on the other – back yards too shallow to permit the widening of the street and construction of houses. (Toronto Star, Oct. 2, 1912)

While City Council pondered the problem and even visited Erie Terrace to see for themselves (Toronto Star, Oct 15, 1912) new houses were going up and the sanitary conditions, with polluted wells from over-flowing outhouses and large numbers living in close quarters.

$150 – NEW house, three large rooms, hall, water and gas, balance $825, at $12 monthly. 62 Erie terrace (Toronto Star, Nov. 16, 1912)

No one should have surprised when typhoid visited from time to time and even smallpox.

Toronto Star, April 1, 1911

Case of Smallpox.

A smallpox case has been discovered at a house in Erie terrace. The patient is a young woman 20 years of age. Three inmates of the house have been quarantined and the patient is now in the Swiss Cottage Hospital. (Toronto Star, Dec. 7, 1912)

More Smallpox.

Another case of smallpox has been taken from the house in Erie terrace which has been under quarantine since December 6, when a woman was taken to the Swiss Cottage. Her husband has contracted the disease and was removed on Saturday night. A woman and a baby are left in the house. There are now four smallpox patients in the hospital. (Toronto Star, Dec. 16, 1912)

Smallpox Quarantine Lifted.

The quarantine has been lifted from the Erie terrace house from which two smallpox cases were taken. The house was closed for three weeks and one day. Providing no other cases develop in the Booth avenue house, the quarantine will be raised on New Year’s afternoon. (Toronto Star, Dec. 30, 1912)

The calls to clean up slums, both in the inner city and in the suburbs, grew louder and louder. The infamous Ward downtown was a prime target, but so was Erie Terrace. Some residents hoped to escape the stigma by changing the name to Erie Avenue, but that got nowhere as the City Street Naming Committee could not have been fooled. (Toronto Star, Nov. 11, 1911)

Widening the street was seen as a magic wand, but unfortunately there were obstacles, namely the inability of Erie Terrace residents to pay for the work and the reluctance of Ashdale Avenue residents who would lose a significant portion of their backyards in the process. Erie Terrace residents supported the widening and were willing to pay both the costs that would normally be assigned to those home owners on the west side as well as the costs they faced as home owners on the east side. Given the poverty they faced, this would entail considerable sacrifices by those families.

Cleaning Up Erie Terrace.

Erie Terrace, with 6,000 feet of frontage exclusive of street intersections, is the biggest problem the city has to face in the shape of a narrow street. It was taken in with the Midway, and its present condition is no fault of Toronto’s. At some places it is only 15 feet wide, at others it is 30. But there are houses on only one side of it, the other side being back yards of houses which front on Ashdale avenue.

What is the city to do with the place? No building permits have been issued there during the past two years, and city conveniences cannot be put in until the street is put in some kind of shape. city Hall officials groan whenever they hear the name.

Ald. Robbins had had the courage to undertake a solution. He wishes the city to buy 15 feet or thereabouts off the back yards in question, so that Erie terrace can be made 45 feet wide. It will be a street with houses on one side, and the owners of these will have to pay the share of local improvements which would be borne by neighbors across the street in ordinary cases. It is said, however, that they would rather do this than have the place remain as at present.

Some people on Ashdale avenue are said to be willing to sell the piece off their back yards for $3 per pruning foot. In that event, the city could get rid of the problem for about $18,000. It remains to be seen what the Council will do with Ald. Robbins’ proposal. Certainly a solution along some line or other should be forthcoming and that without delay. Toronto Star, Jan. 15, 1913

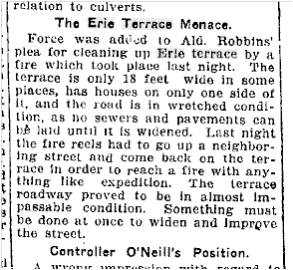

Erie Terrace now ran all the way from Queen to the railway tracks and north to Danforth Avenue. It was graded, but still too narrow for the City’s fire trucks to get up the street. Since the houses were wooden and tarpaper (notoriously inflammable), if one house went up, a whole neighbourhood could burn which is why it was considered not just disgraceful, but a menace to others.

Force was added to Ald. Robbins’ pleas for cleaning up Erie terrace by a fire which took place last night. The terrace is only 18 feet wide in some places, has houses on only one side of it, and the road is in wretched condition, as no sewers and pavements can be laid until it is widened. Last night the fire reels had to come up a neighboring street and come back on the terrace in order to reach a fire with anything like expedition. The terrace roadway proved to be in almost impassable condition. Something must be done at once to widen and improve the street. (Toronto Star, Jan. 21, 1913)

Alderman William Dullam Robbins, who represented the area, pressed his solution.

And still Shacktown’s population grew while the problem of the strait and narrow street did not go away. From $3.00 a foot in 1906 frontage was now selling at $12 a foot.

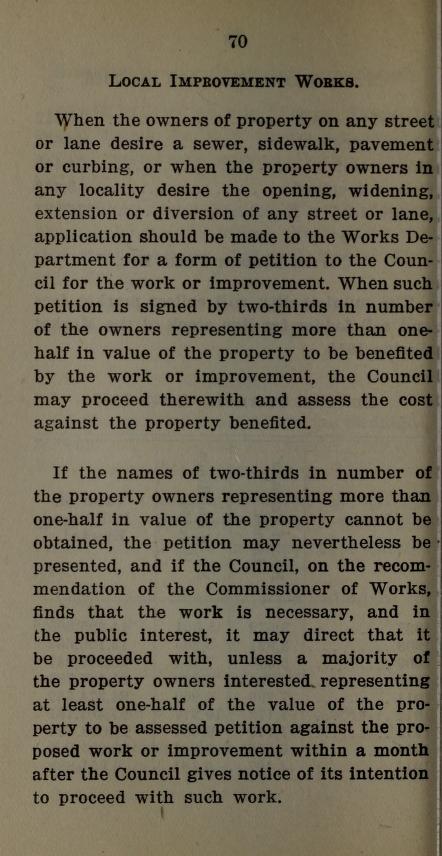

While City Council did approve widening the street, progress was slow due to the inability of those on Erie Terrace to pay for the work. Works Commissioner R. C. Harris was reported to have said that “the conditions of life on Erie terrace were anything but satisfactory, and that the widening of the street was a necessity”, unfortunately, the City couldn’t wring blood or money out of the stone that was Erie Terrace. Here is the process as described in The Municipal Handbook: City of Toronto, 1916:

The street was now almost full as Goad’s Atlas of 1912 shows. What it doesn’t show is the large numbers of children in each family. With a war time housing crisis, families doubled up in those tiny houses and many took in roomers or boarders to make ends meet.

Goad’s Atlas, 1912

In 1913 it seemed the solution to “The Erie Terrace Problem” was near. The City meant business. “A petition against the said proposed work will not avail to prevent its construction.”

The problem could be summed up as a question of rights. If the Erie Terrace people were to pay double the normal cost for widening the street, why should those people on Ashdale Avenue gain the benefit of better access to their backyards? The street was widened but a reserve strip would be kept so that the Ashdale avenue owners could not build any new structures, especially houses, in their truncated backyards. Meanwhile those with bigger and better houses on Ashdale Avenue developed a seething resentment at those living in the squalor of Erie Terrace, especially when those unwelcome neighbours trespassed by taking short cuts through the Ashdale backyards. (Toronto Star, Oct. 7, 1913)

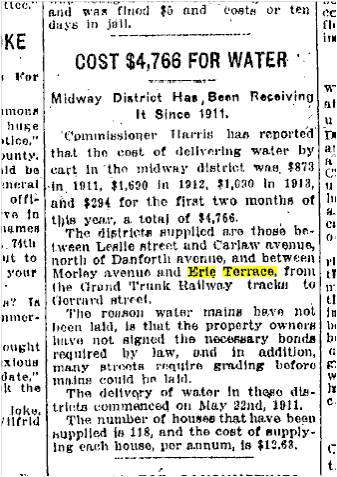

Meanwhile, none of the streets between Morley Avenue and Erie Terrace from Gerrard to the rail lines had water mains. No one could use the wells since they were so badly contaminated. The City of Toronto trucked in drinking water until the streets were improved enough to lay mains and the residents had signed the necessary documents agreeing to pay for the work. 118 houses had water supplied to them and the cost of delivering the water was climbing rapidly as the population increased. The City had little choice. The groundwater was contaminated by hundreds of outhouses and typhoid was a constant threat…one that would not confine itself to Erie Terrace. Even more affluent people could catch it from poorer people. (Toronto Star, March 12, 1914)

Toronto’s one and only sewage plant was now operating at the foot of Morley Avenue (Woodfield Road) and the City called for tenders to lay the sewers on the easiest part of Erie Terrace: from the rail line to Danforth Avenue. (Toronto World, July 1, 1914).

Seemingly little things began to rankle. Horses and wagons and even cars continually drove up Erie Terrace with one wheel on the road and the other on the sidewalk. This avoided getting stuck in the deep ruts and the quicksand the area was notorious for, especially after rains. But it smashed the wooden sidewalk (just two planks on cross beams). Erie Terrace residents asked for a permanent or cement sidewalk, but could not get it because they couldn’t pay for it. (Toronto Star, March 26, 1915) However, the City did agree to grade and widen Erie Terrace at a cost of $9,300 of which the City would pay $4,800 and the residents would be on the hook for $4,500. The work would begin in the spring of 1916. (Toronto Star, October 23, 1915).

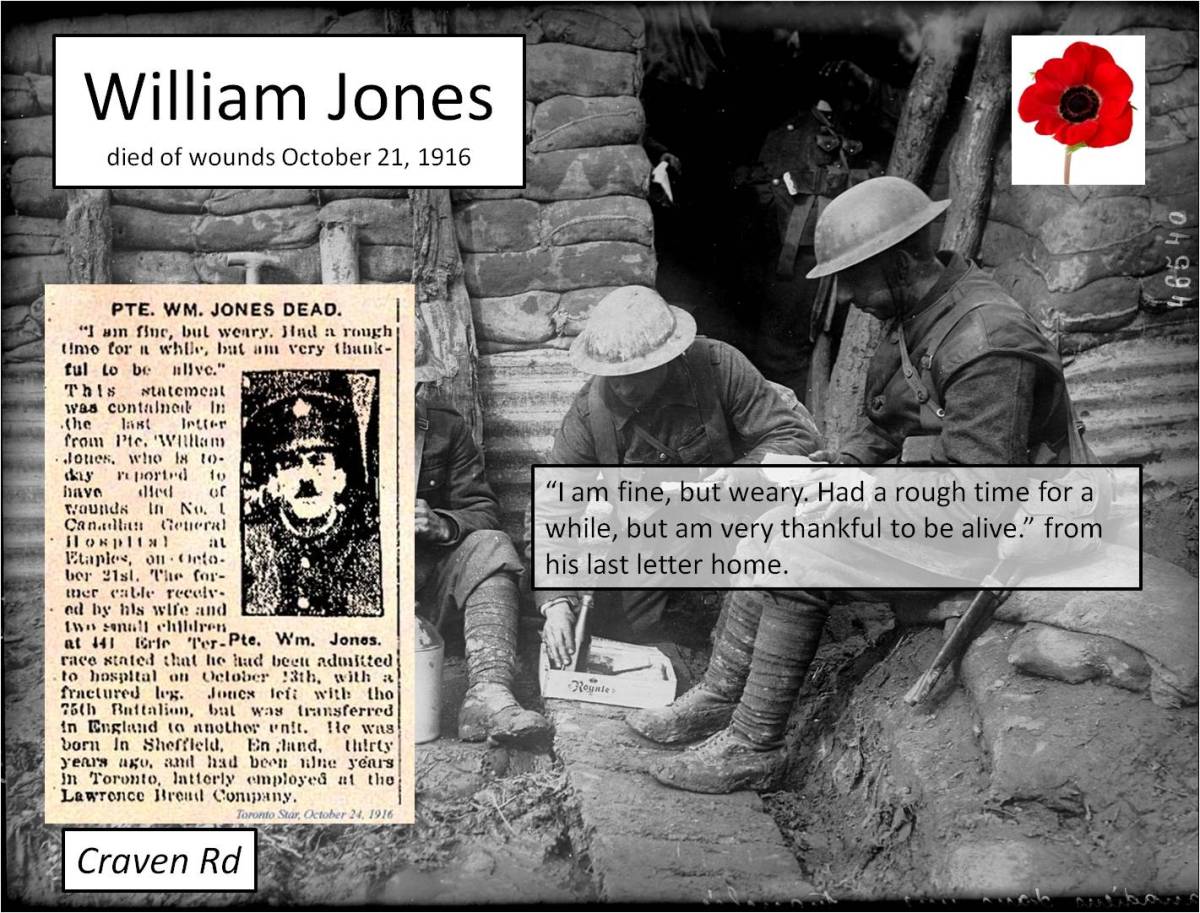

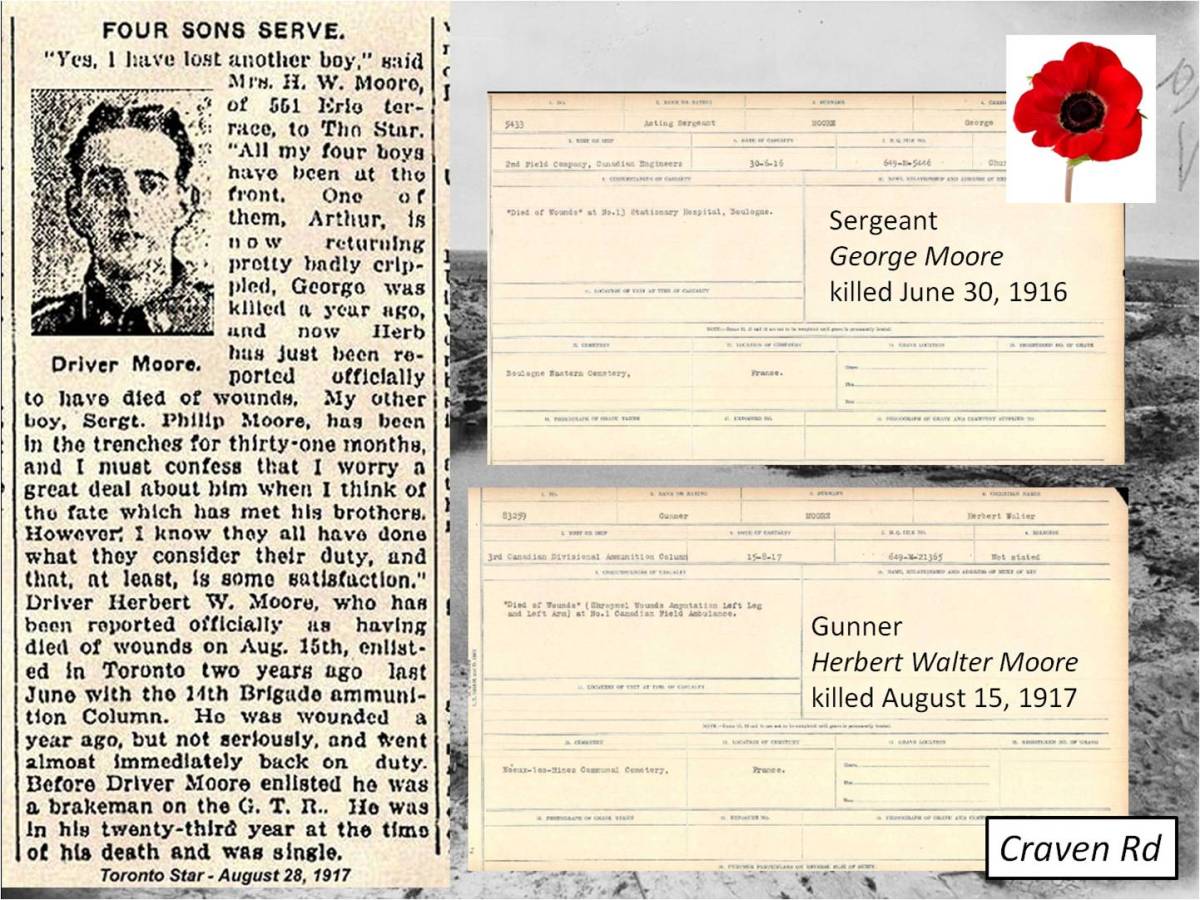

It was until 1916 that most of the men were finally employed — as soldiers. (Toronto Star, March 1, 1913) Though army pay was low ($1.00 a day for privates — the lowest rank), many men sent most of their pay home through automatic deductions from their pay as well as through the mail. The added separation bonus of $25 a month for married men, added to their pay, added up to far more than many had earned before the Great War. Not surprisingly, after years of unemployment, the enlistment rate on Erie Terrace was incredibly high, as were the casualties. Patriotism was one motivation, economic necessity was another.

It was until 1916 that most of the men were finally employed — as soldiers. (Toronto Star, March 1, 1913) Though army pay was low ($1.00 a day for privates — the lowest rank), many men sent most of their pay home through automatic deductions from their pay as well as through the mail. The added separation bonus of $25 a month for married men, added to their pay, added up to far more than many had earned before the Great War. Not surprisingly, after years of unemployment, the enlistment rate on Erie Terrace was incredibly high, as were the casualties. Patriotism was one motivation, economic necessity was another.

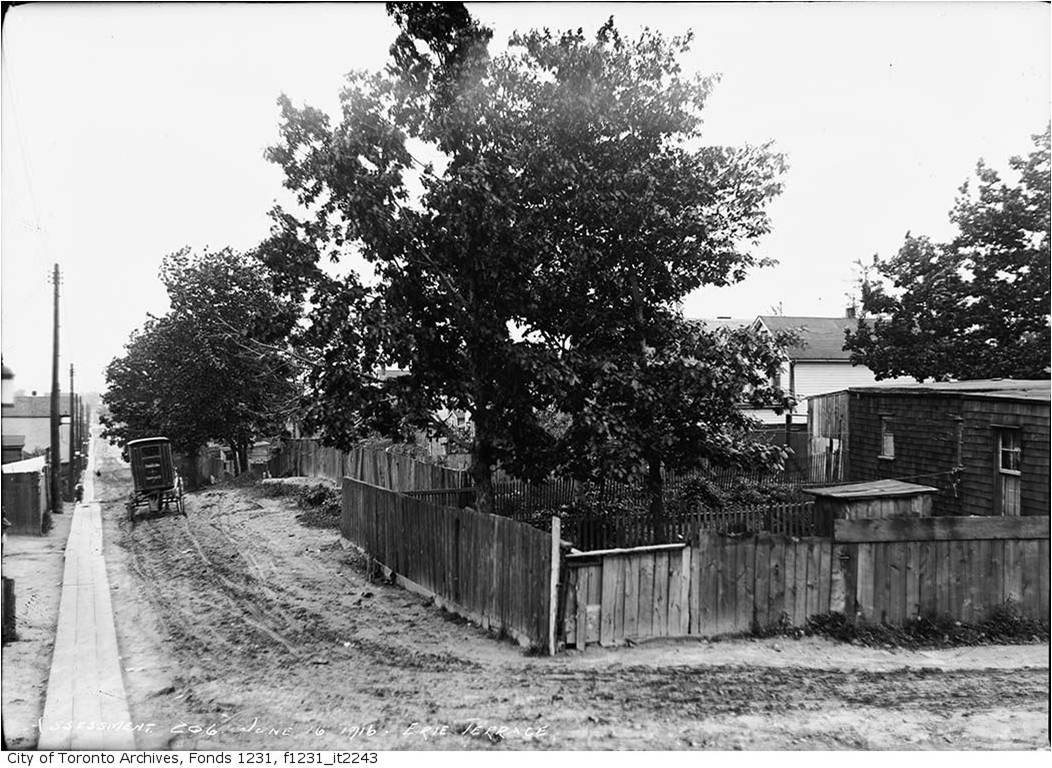

By 1916, the City of Toronto had resolved to move forward on the engineering problem of widening and improving the road bed of Erie Terrace. They would put up a fence on the west side of Erie Terrace from Queen to the rail line and maintain it perpetuity. The City fathers now felt that they could engineer a solution to the menace that was Erie Terrace, a complicated problem made simple with a fence.

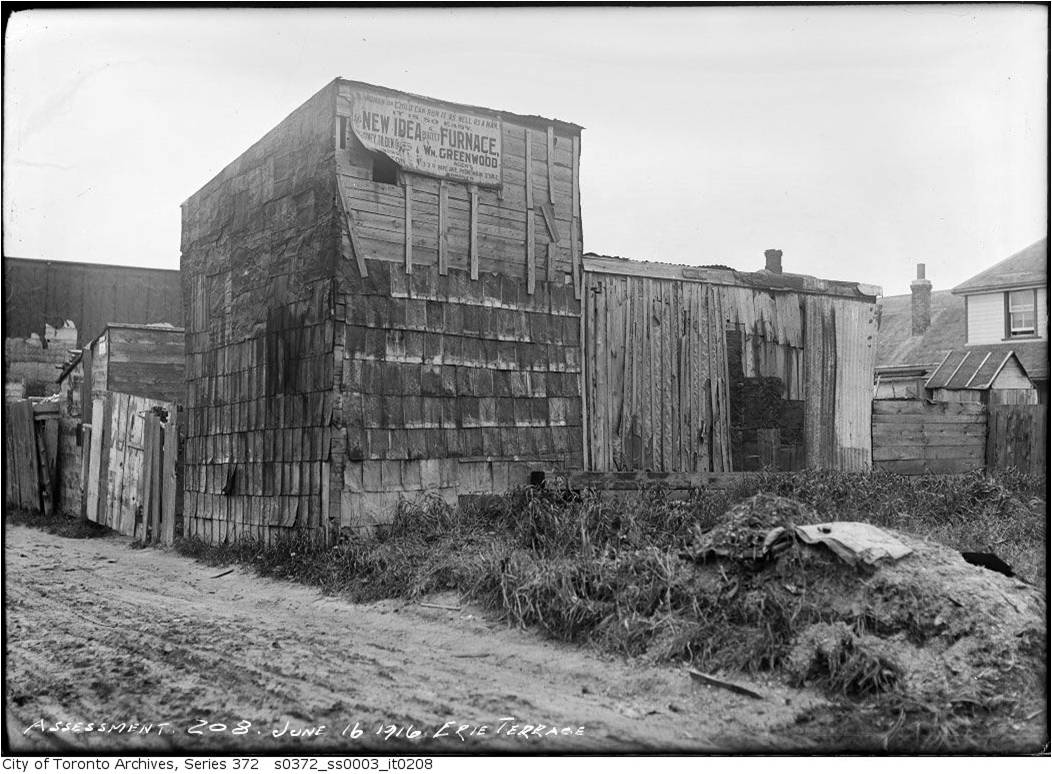

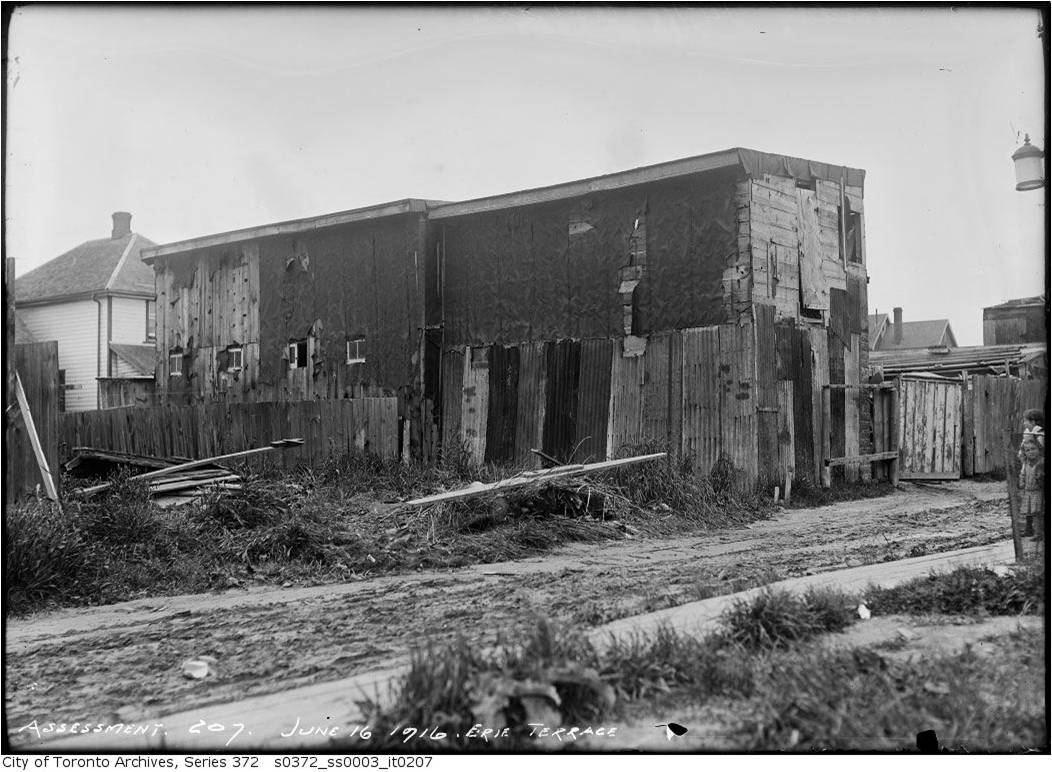

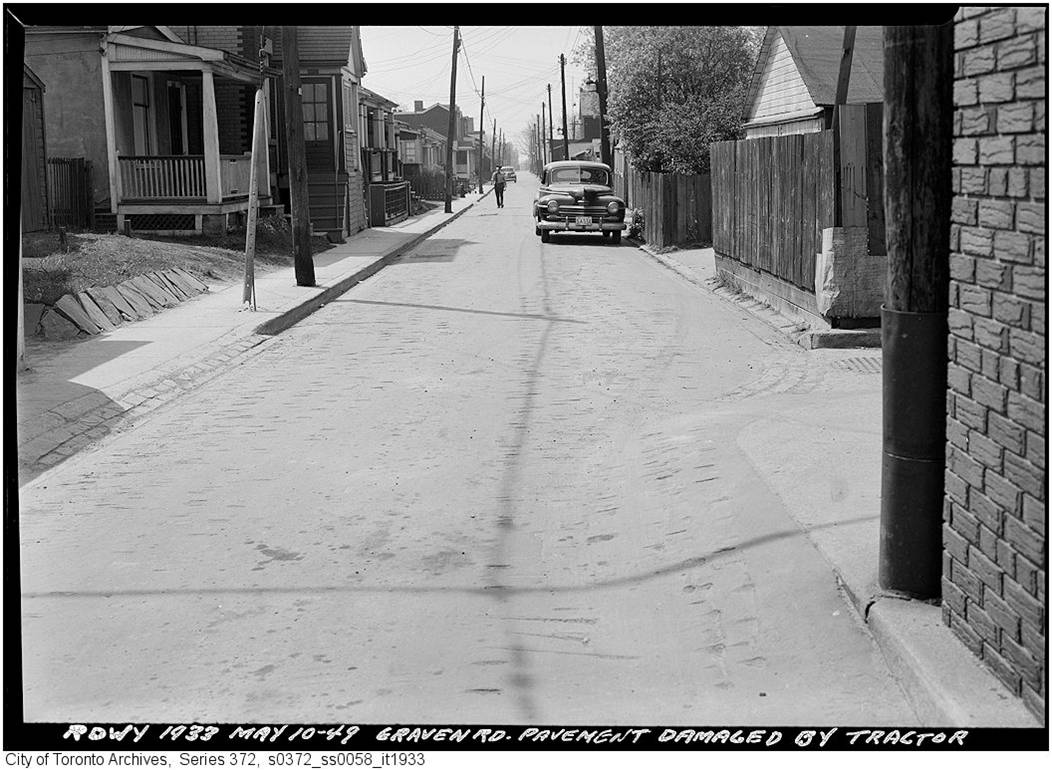

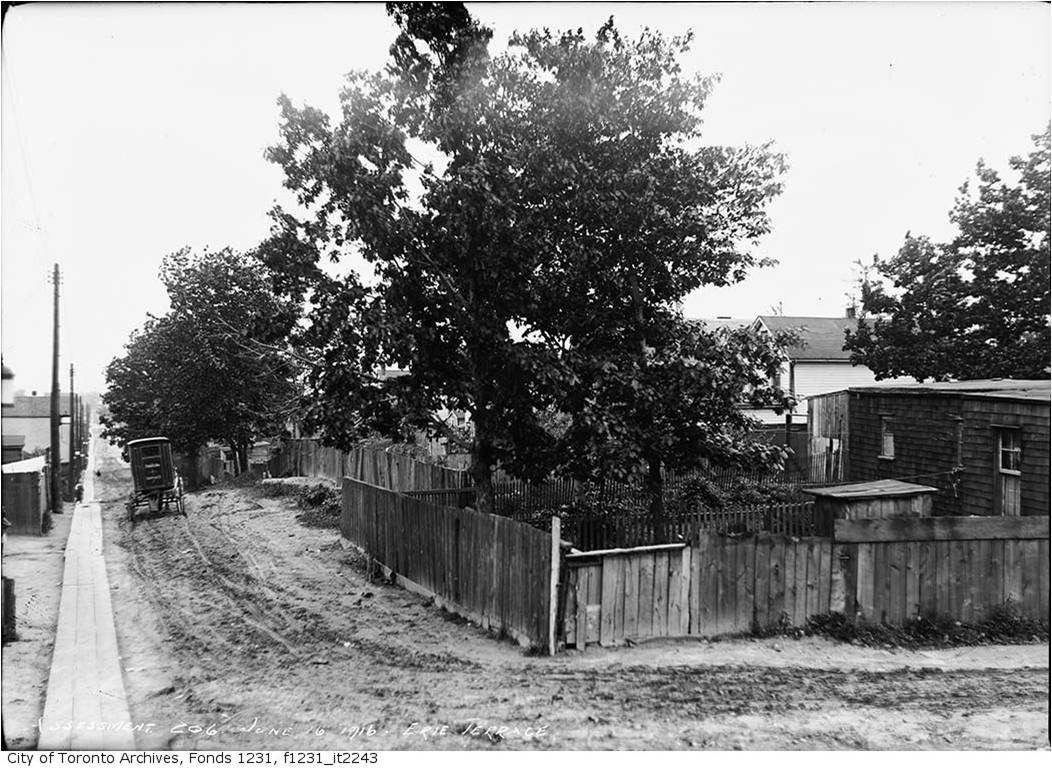

These photographs were taken by the City of Toronto Assessment Department after the expropriation of the back yards of Ashdale residents to widen Erie Terrace, but before the City put the fence up. Unfortunately we have no “after pictures” to go with these “before” shots.

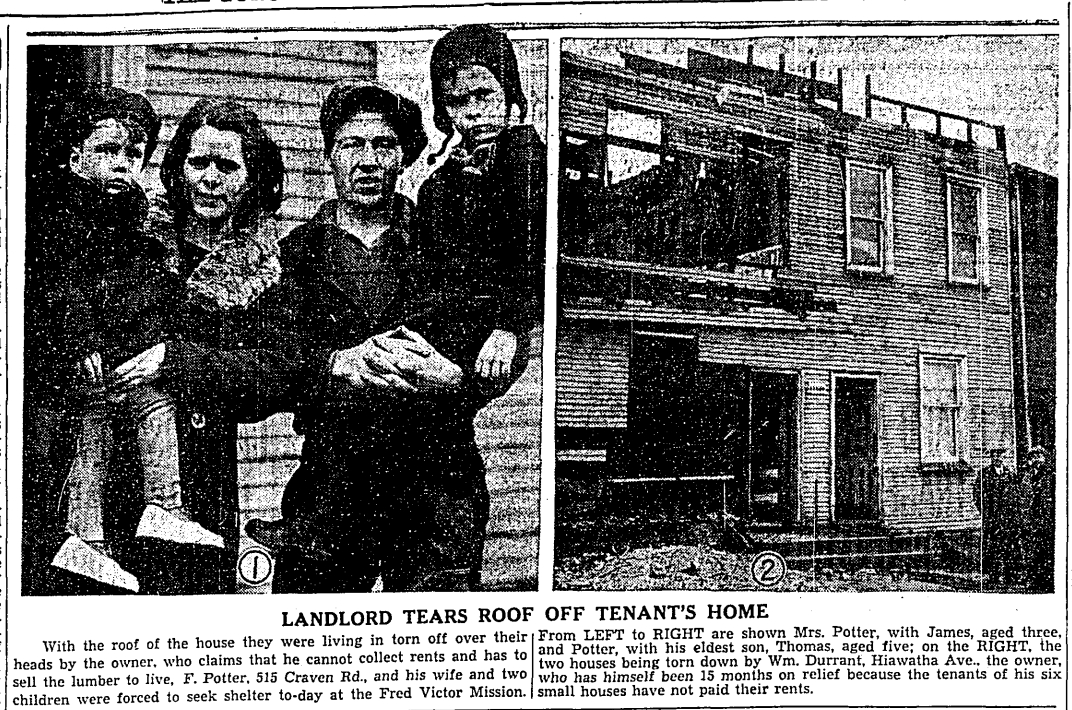

The people on Erie Terrace did not want the Ashdale Avenue people to use the widened road because the Erie Terrace people had paid double for it and the Ashdale Avenue people had not paid anything. The people on Ashdale were only slightly more affluent than those on Erie Terrace, but Erie Terrace had a reputation for squalor, crime, prostitutes, drinking, etc. So the people on Ashdale wanted the Erie Terrace people out of their back yards. In the days before cars and the need for backyard parking spots, this solution, the Fence, suited both the Erie Terrace folks and their slightly more well-heeled neighbours on Ashdale Avenue.

The people on Erie Terrace did not want the Ashdale Avenue people to use the widened road because the Erie Terrace people had paid double for it and the Ashdale Avenue people had not paid anything. The people on Ashdale were only slightly more affluent than those on Erie Terrace, but Erie Terrace had a reputation for squalor, crime, prostitutes, drinking, etc. So the people on Ashdale wanted the Erie Terrace people out of their back yards. In the days before cars and the need for backyard parking spots, this solution, the Fence, suited both the Erie Terrace folks and their slightly more well-heeled neighbours on Ashdale Avenue.

The City, meanwhile, did not want the Ashdale Avenue people using their now much smaller backyards for garages and sheds. (The dilapidated sheds were used for horses, in most cases, as few had cars in this “streetcar” suburb.) The City had expropriated part of the Ashdale Avenue backyards to widen Erie Terrace. But what was left of those backyards didn’t have enough of a setback under Toronto Bylaws for building anything. Therefore, the fence is maintained by the City of Toronto despite periodic attempts to have it removed or partially dismantled. Not everyone liked the fence then and not everyone likes it now. (Toronto Star, March 23, 1916)

The City, meanwhile, did not want the Ashdale Avenue people using their now much smaller backyards for garages and sheds. (The dilapidated sheds were used for horses, in most cases, as few had cars in this “streetcar” suburb.) The City had expropriated part of the Ashdale Avenue backyards to widen Erie Terrace. But what was left of those backyards didn’t have enough of a setback under Toronto Bylaws for building anything. Therefore, the fence is maintained by the City of Toronto despite periodic attempts to have it removed or partially dismantled. Not everyone liked the fence then and not everyone likes it now. (Toronto Star, March 23, 1916)

That summer the City of Toronto expropriated the Ashdale Avenue backyard property it needed to widen the road and took pictures of Erie Terrace before it did the work.

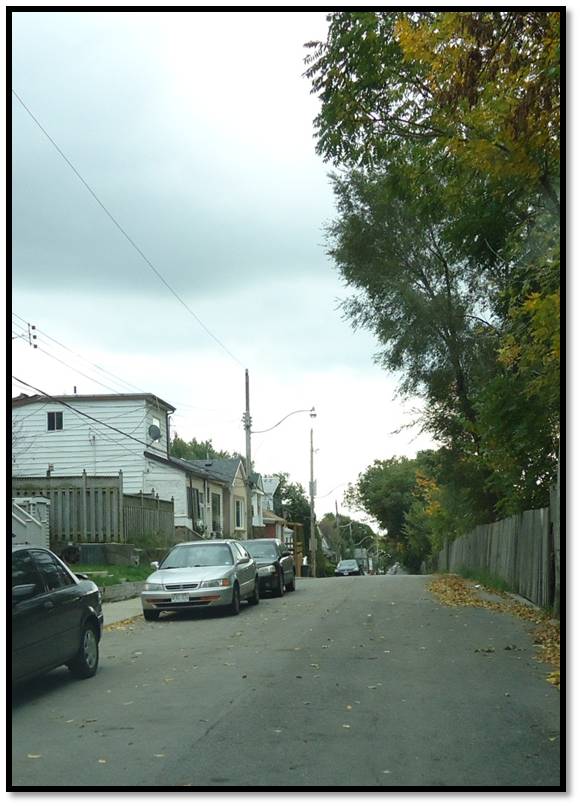

Erie Terrace, June 16, 1916

Erie Terrace, June 16, 1916

I first started investigating Craven Road in 2002 when someone I knew from an America On Line birding board asked me if I could find out where Erie Terrace was, how his great grandfather died and why his great grandmother had to put her three little boys in an orphanage and risk losing them. The soldier was George Threlfall and his wife was Emma Elizabeth McDonald. He died on December 1, 1916 most likely died of influenza, in a precursor of the 1918-19 Spanish flu epidemic. Because he did not die in action overseas, his wife did not get the full pension she needed to house, feed and clothe her sons.

But he was just one of many who died on Erie Terrace during the Great War To End All Wars. The City of Toronto was now able to wring the money it wanted out of Erie Terrace and others in the East End now that virtually all of the men were working…most in the trenches. Some might say that the War built that fence.

But he was just one of many who died on Erie Terrace during the Great War To End All Wars. The City of Toronto was now able to wring the money it wanted out of Erie Terrace and others in the East End now that virtually all of the men were working…most in the trenches. Some might say that the War built that fence.

More improvements followed.

More improvements followed.

LOCAL IMPROVEMENT NOTICE

Applegrove Avenue Extension Take notice that the Council of the Corporation of the City of Toronto intends to extend Applegrove Avenue at a width of 66 feet from Ashdale Avenue easterly to Coxwell Avenue, and intends to specially assess a part of the cost upon the land abutting directly on the said work, and upon certain other lands hereinafter mentioned, which will be immediately benefited by such extension. The estimated cost of the work is $27,000, of which…$7,103 is to be paid by the Corporation. (Globe, March 29, 1918)

The rest of the cost was passed on to those living nearby on Applegrove Avenue, Morley Avenue, Hiawatha Road, Kent Road, Ashdale Avenue, Rhodes Avenue, Coxwell Avenue and Erie Terrace.

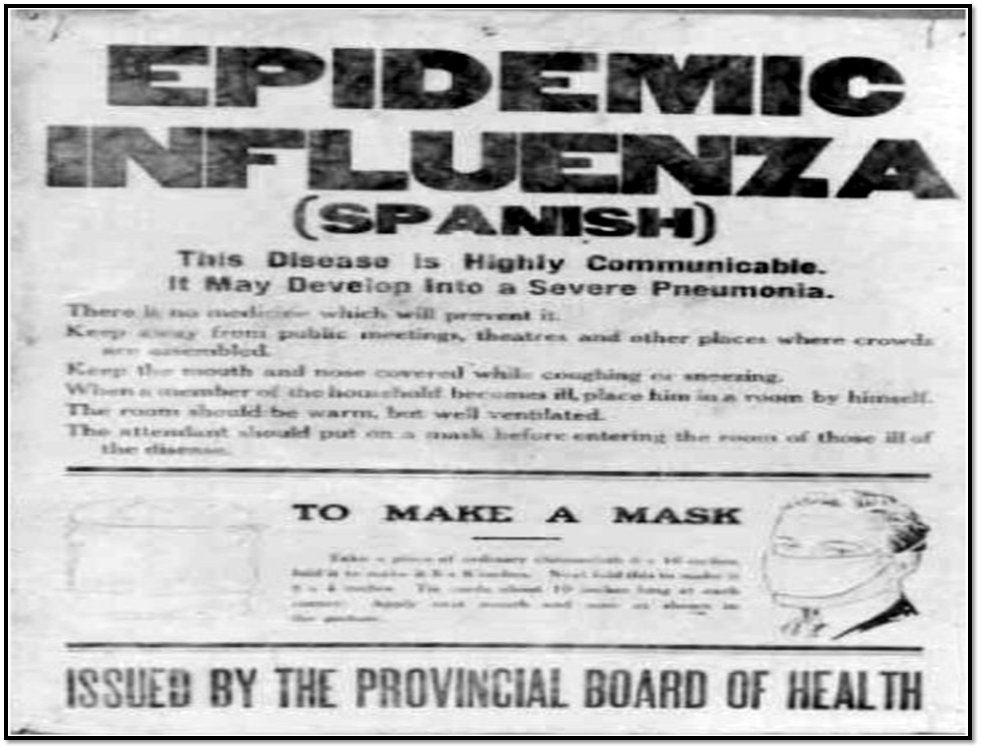

While the War ground on, the Spanish flu hit, seemingly out of nowhere, spread from military base to military base and brought home by the returning soldiers. Older people seemed to have some resistance to it, but the young did not.

While the War ground on, the Spanish flu hit, seemingly out of nowhere, spread from military base to military base and brought home by the returning soldiers. Older people seemed to have some resistance to it, but the young did not.

Dr. Hasting Forbids Conventions In City

Over 300 New “Flu” Cases are Reported at the City Hall.

List of the Deaths Increase Reported in the Schools – 50 Per Cent Absent From Some of Them

Dr. Hastings issued strict orders to-day that under no condition must conventions of any kind be held in Toronto until the present epidemic of influenza had died out.

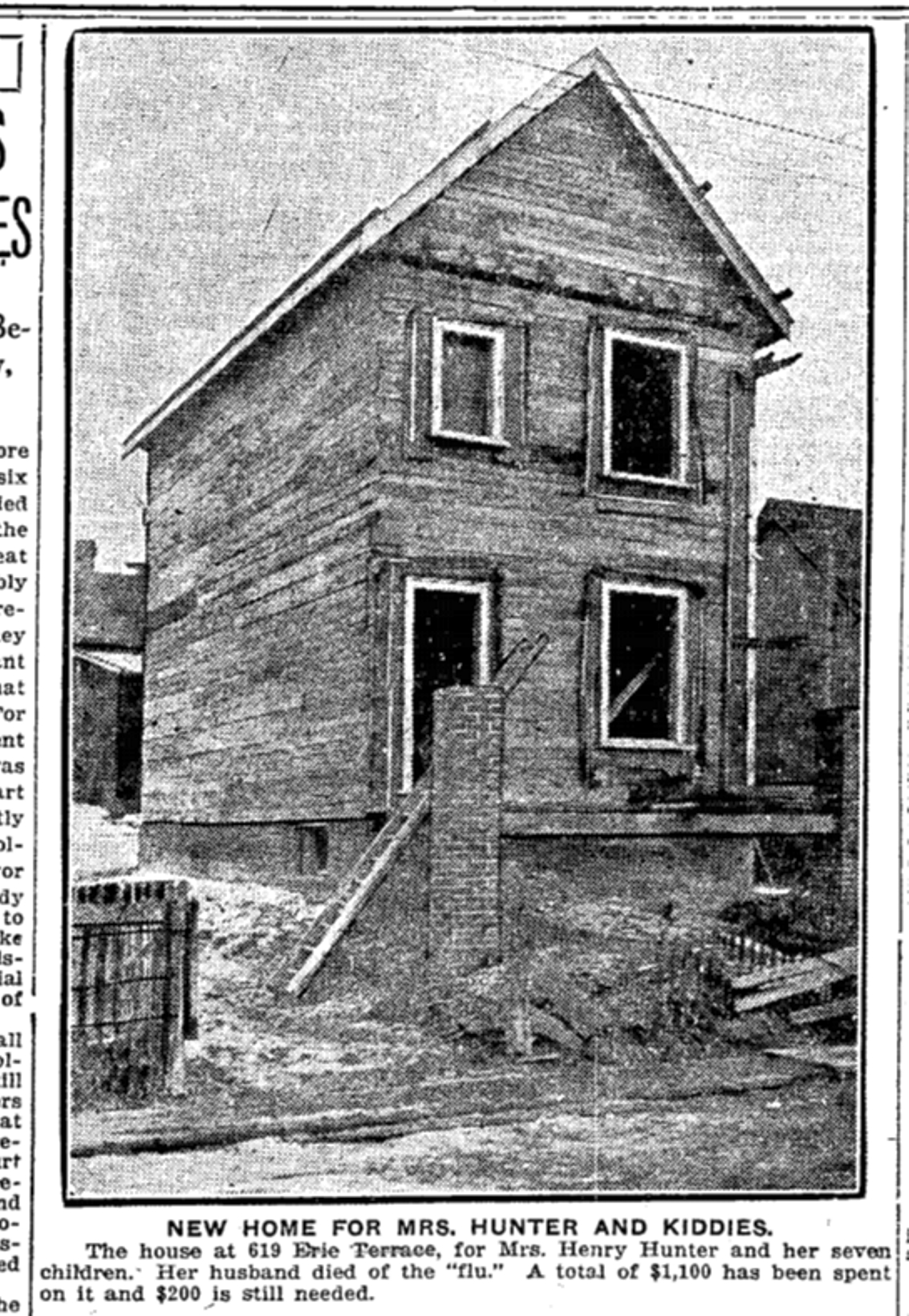

There were forty new cases reported to the Department of Health this morning, while others will come in during the day. Up to date, 170 have been reported to the department. This, however, does not by any means represent the number of cases in the city, as there are over 300 cases in the hospitals alone….Up to noon to-day the following deaths from pneumonia and influenza had been reported since yesterday: … [Died of influenza] Walter J. H. Barber, 15 years, 206 Ashdale avenue. … Henry Hunter, 37 years, 589 Erie terrace. Martha Mitchell, 62 years, 4 Fairford street. …Rosie May Jones, age 37, of 19 Jones avenue. Agnes M. Ferguson, age 17, of 114 Logan avenue. Nellie McNelley, 201 Morley avenue…The epidemic of Spanish influenza in the Toronto schools is on the increase, according to information received by The Star this morning. In many of the larger schools as many as 50 per cent of the pupils are away, and in practically every school in the city, a large percentage is away sick. (Toronto Star, Oct. 11, 1918)

The street was coming back to life.

In 1913 the Reliance Loan and Savings Company of Ontario was amalgamated with the Standard Loan Company under the name “The Standard Reliance Mortgage Corporation.”

In July, 1919, a financial scandal made the news as the Standard Reliance Mortgage Corporation, with its subsidiaries, including the Dovercourt Land Company, went under and an investigation followed. Improper transactions shocked investors. A number of other companies were involved including the Investors’ Land Company, Kendal Hill Company, and Robins Real Estate.

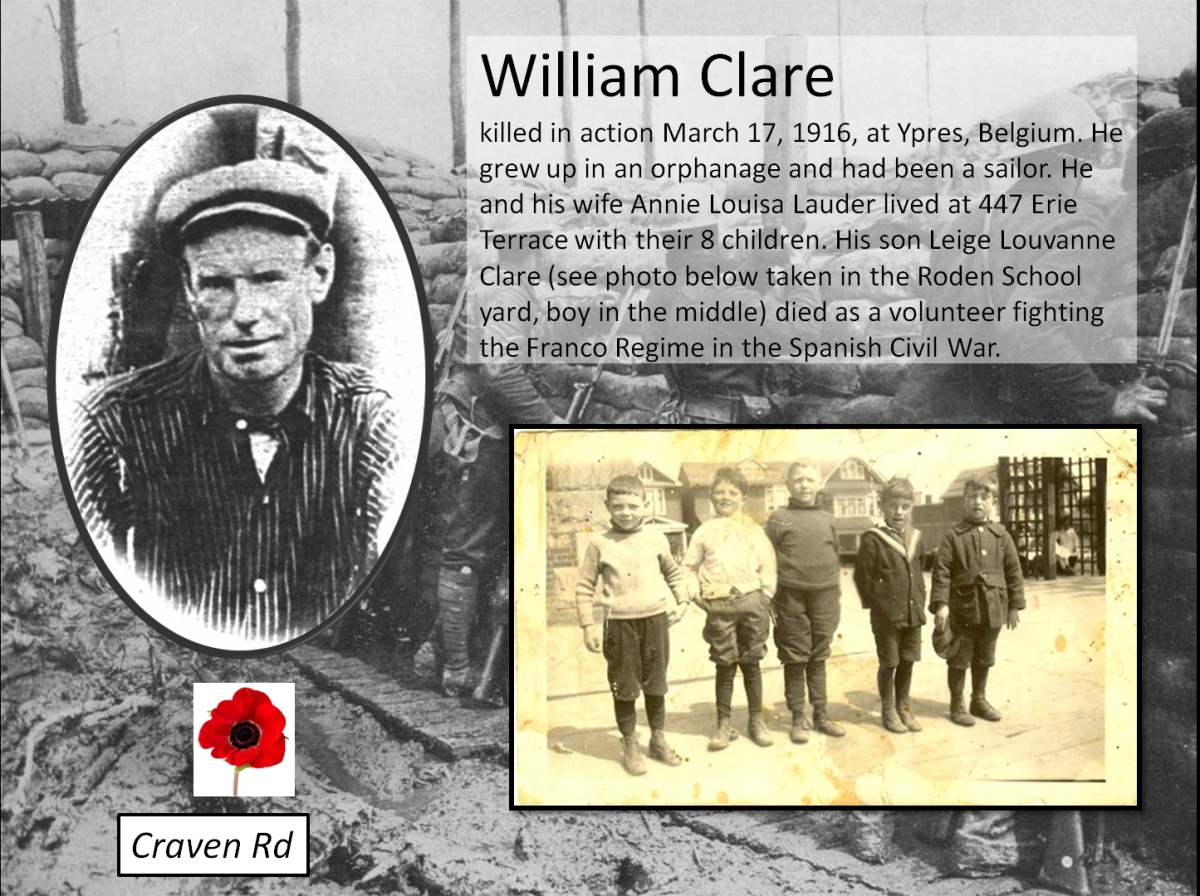

The First World War cut deep into the heart of Erie Terrace. World War I cost Toronto 10,000 lives. This odd, long street of tiny houses on only the east side contributed a disproportionate number of men to enlistment. Most were in the infantry and in the trenches of Belgium and France. Many did not come home or came home so wounded that they could not work. At the end of the Great War, Erie Terrace stood emptied of many of its men, a street of widows without adequate pensions or a way to make a living. Some had to give up their children, sending them to orphanages. Many women went into domestic service downtown or sought other jobs elsewhere and left. Some remarried. Some stayed. The spirit of Erie Terrace remained strong and neighbours, though poor themselves, continued to help neighbours out.

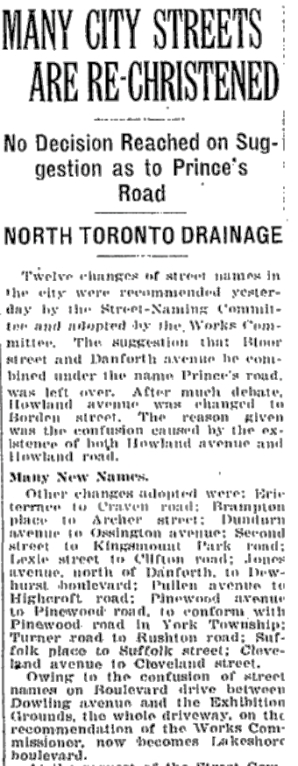

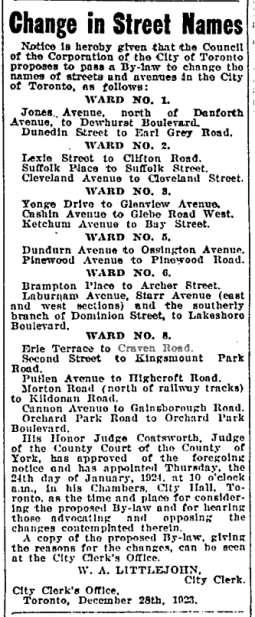

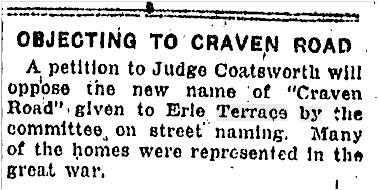

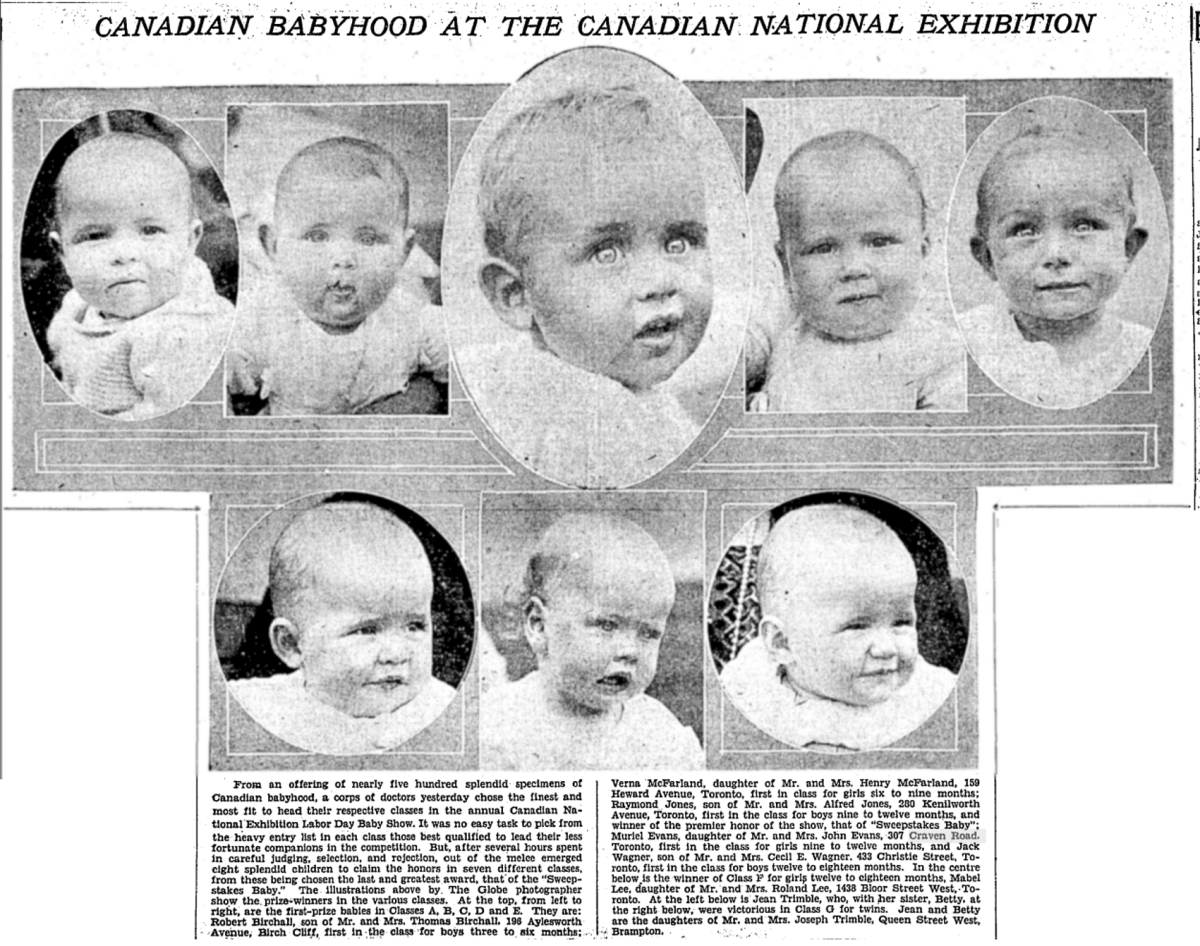

In 1923, Erie Terrace was renamed Craven Road, despite objections that the men of Erie Terrace were brave and “had done their bit” overseas. Craven Road was supposed to take away the stigma of the street, but the stink of the glue factory at Coxwell and Gerrard and the foul “Morley Avenue perfume” from the sewer plant echoed the phrase, “A Rose by any other name smells as sweet”.

“Craven” also means “cowardly, lily-livered, faint-hearted, chicken-hearted, spineless…” and even gutless. A simple Google search will bring up even more bad things about “Craven”. Given the street’s record of enlistment and the casualties sustained in World War One, many were outraged at the name change.

Globe, Dec. 28, 1926

The emptied houses quickly filled with returning veterans desperate for homes in a post-war housing crisis. New homes filled in any vacant lots on Erie Terrace and brick bungalow replaced many shacks. If a family could not afford a brick house, they often had the front of the house faced with brick and covered the sides with tarpaper or Insulbrick, a kind of artificial brick still made today.

Goad’s Atlas, 1921 – There are many more “Mrs.” than before. Only “heads of household” were listed. If a woman had a living husband, she was not listed. These were not old women, but young women, widows of soldiers (e.g. Mrs. Anne Clare, Mrs. Mary Vandusen) and men who died of the flu (e.g. Mrs. Phoebe Hunter).

Men and women turned to rebuilding their lives, having babies, raising their children and watching over their fence.

Enter a caption

One thought on “The Fence”