Welcome to Alton Avenue in Toronto’s old East End, once farm fields in Leslieville and now part of a rediscovered Leslieville. Consider this an aide to assist you in your enjoyment of this street. I hope you love it as much as I have over the years as I’ve walked up from Queen to Gerrard, or down from Gerrard to the dog park with Ley the Border Terrier. This short history of Alton Avenue tells of its development, growth and another dog, from 1919, that was too smart for his own good.

Alton Avenue only makes sense if you know a little about the Devil’s Hole or Devil’s Hollow because it slowed the subdivision of the property between Hastings and Greenwood long enough to allow Greenwood Park to be born. It determined the streetscape and why some houses were built ten years later than most and have a different architecture. It made Alton unique when it could have been just another street of old duplexes, triplexes and single family homes from that great period of Toronto’s expansion before World War One.

This Goad’s Atlas map of 1884 shows two creeks running through the heart of Leslieville as thin winding lines. The western creek was Leslie Creek and the eastern creek was Hastings Creek.

Here is another map of Hastings Creek as it ran through a deep ravine from springs north of the Danforth, cutting a 90 foot deep ravine known as the Devil’s Hollow from the railway track across Gerrard Street and through what is now Greenwood Park.

Its course south of Dundas Street meandered through the field between Alton and Hiltz, crossed Queen Street East where the Beer Store is today. It flowed through Maple Leaf Park (west of Maple Cottage on Laing Street). It flowed at a slower, more sedate pace, become shallower as it approached Ashbridge’s Bay. It entered the Bay at the cove known as “The Gut” at Eastern and Leslie where the Loblaw’s Superstore is today.

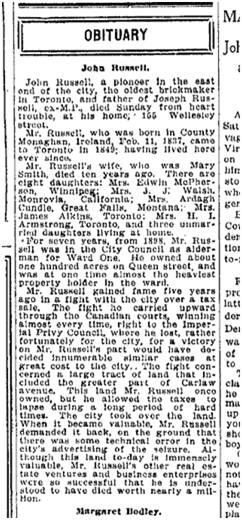

In 1906 there was no Alton Avenue, Hiltz Avenue or Dorothy Street. Instead there was a massive brick plant, the largest in Canada, with a brick pit that stretched from Queen Street almost to Gerrard Street in the north and from just east of Hastings Avenue in the west to Greenwood Avenue in the east. Clay, sand and water are needed to make bricks. Joseph Russell Jr., brick manufacturer, widened and deepened the Devil’s Hollow both north of Gerrard and south of Gerrard to extract clay to make high quality bricks and his fortune. The photo of Joseph Russell below is from The Toronto Star, June 17, 1914.

The Russell family was large and influential. Joseph Russell Sr. (1808-1892) was an Irish brick manufacturer who came to Canada in 1849 and settled in Leslieville. He opened a brickyard between Logan and Verral north of Queen where the Value Village is today. He developed brick yards throughout the area. At the time of his death his home was at 910 Queen Street East, on the north-east corner of Logan and Queen. He and his wife Martha had four sons:

- John Russell (1837-1912)

- William Russell (1844-1910)

- James Russell (1845-1912)

- Thomas Russell (1847-1886)

John Russell married Mary Smith. They had ten children: nine girls and one boy. Their son, Joseph (1868-1925) was the brick manufacturer, politician and dog fancier who ran the brickyard where Alton, Hiltz, Dorothy, Parkfield, Stanton, and Sawden are today. The death of John Russell in 1912 triggered the sale of the brickyard at Greenwood and Queen. Real estate had to be liquidated in order to divide the Estate amongst his ten children.

William Russell married Jane Sample. They had eight children: four girls and four boys. One of their sons, John Edward Russell (1872-1934) was a major contractor responsible for much of the Toronto Harbor Commission’s sea wall and other waterfront construction. He was also a major ship owner.

This 1908 map shows the Devil’s Hollow and the course of Hastings Creek, perhaps now straightened a little by the brick yard workers as they dug out clay along its course.

In 1908 there were still no streets through the muddy, barren brick pit. It would be a formidable challenge to anyone hoping to develop it as a subdivision. The surface, was basically flat with steep cliffs on the north, west and east sides. The bottom was pitted and uneven, but most of all it was wet, soaked, even in dry summers. Rainwater and groundwater from springs and seeps in the brick pit had nowhere to go except the creek. The hard-packed clay at the bottom of the brick pit was hard, cement-like and almost impervious. Water ponded in the craters dug by the brick workers. This map also shows the deep ravine that was the Devil’s Hollow. Because of the ravine and the brick pits Hastings only ran up about half way to Gerrard at this point.

1908’s City Directory shows no Alton Avenue or Hiltz — yet.

This 1909 map shows in pink the area to the east of Greenwood Avenue that was in the Township of York and became part of the City of Toronto that year. The deep ravines were cut by Hastings Creek on the left and Ashbridges Creek on the right. Both significantly delayed or prevented development of part of the area for housing.

Goad’s Atlas of 1910 shows that the area was subdivided into fairly large lots, these being more wishful thinking than reality. Goad’s Atlas often does not show creeks, but Hastings Creek was still running through the Devil’s Hollow. The large yellow buildings are Russell’s brick plant. There are a few houses (some owned by brick makers like the Morleys) and a few stores on the north side of Queen Street. Goad’s Atlas is very accurate for buildings but doesn’t attempt to deal with natural features or topography. Creeks, hills, swamps, etc. often are not shown.

1910

This is a view from Hastings Avenue looking east along Queen Street. The bridge over the creek is clearly visible and large trees are growing in the ravine. Local people also called Hastings Creek after William Laing the boat builder whose workshop was on “Laing Creek” or “crik”.

This is the same view. Photo by Julia Patterson. The Beer Store is where the bridge was. The Creek and (probably the bridge too) is buried under Queen Street.

In 1912 John Russell died. The Estate of John Russell, Joseph Russell’s father, offered to sell 15 acres on the east side of Greenwood to the City of Toronto for a park, along with 25 acres from Queen Street. The City sold some its property on the south side of Gerrard Street in 1912. Builders put up new stores and some houses there including the one that is now the Brickyard Grounds.

In 1912 John Russell died. The Estate of John Russell, Joseph Russell’s father, offered to sell 15 acres on the east side of Greenwood to the City of Toronto for a park, along with 25 acres from Queen Street. The City sold some its property on the south side of Gerrard Street in 1912. Builders put up new stores and some houses there including the one that is now the Brickyard Grounds.

Joseph Russell tore the brick plant down in 1912, but the parks did not happen. The Parks Committee wanted to go ahead with at least one park, but City Council did not agree, yet.

Joseph Russell, sold 55 acres on Gerrard Street East from Hastings to Greenwood Avenue and from Gerrard south to what is now Dundas Street on behalf of his father’s Estate. He moved his brick making operations to Blake Street. Monarch Realty Company and Tanner and Gates laid out a subdivision on the land, including new streets even streets where Greenwood Park is today.

January 14, 1913

They had to do considerable grading and levelling and even then the centre part of the property was too poorly drained and too costly to improve for housing. According to Joseph Russell:

The land on all sides has been built up and the property became too valuable for brickyard purposes.

Tanner & Gates (the owners of Monarch Realty) developed the Ashbridges estate north of Greenwood. The brickmakers had not got their hands (or steam shovels) on this property. It was Ashbridge’s Bush or Greenwood’s Bush, a forest, part of which became Monarch Park, the park, and part, Monarch Park, the subdivision. It was far easier to sell, being high and dry than low muddy Alton.

Tanner and Gates began building in 1913 on Alton Avenue (officially “Alton Street”). However, Alton Avenue was just a short dead end street north of Doel Avenue (which later became part of Dundas Street East). The brickyard’s steep cliff at the north allowed no connection to Gerrard Street East.

The soggy conditions of the ground along Alton Avenue south of Doel (Dundas) to Queen perhaps encouraged Monarch Realty to sell its property there to another realty company, Meen & Meen (Benjamin and John Meen). They had better sites to sell.

Toronto Star, June 21, 1913

Meen & Meen marketed their new subdivision as “Queensvale” referring to both Queen Street and the gully through the area. “Queensvale” has a more attractive ring than “Devil’s Hollow” or “Devil’s Hole”. Their first target audience were builders who would buy up lots cheaply and either hold them as an investment or build on them and hope to sell them as soon as possible for quicker money. Only solid brick or stone houses could be built, no shacks or flimsy do-it-yourself jobs. Alton Avenue was never a “Shacktown” like some of the streets further north and east such as my own street, Woodfield Road. This made Alton distinctive, as well as the uniform 15 foot set back from the street. This is so unlike many older Leslieville streets where the streetscape is more “higgledy piggledy” with some houses sitting ten feet back, the neighbour 15 feet and another neighbour 13 feet, all by whim but without design.

This advertisement of Aug. 8, 1913 exaggerates. The City of Toronto planned to extend Wilton Wilton through the East End, but it didn’t happen until Dundas Street was built in the mid-1950s. There never was a Wilton east of the Don though Fairford Avenue is a remnant of the planned right-of-way. . And there was a reason Alton Avenue was “the closest-in undeveloped building land on the market”: it was a soggy, messy brick pit with a creek through it. The area was growing rapidly, but Alton Avenue with its drainage problems was not the choicest site.

Housing gobbled up the better sites, the land that was not brickyard, as British immigrants poured in, reinforcing its Britishness. The area along Gerrard between Greenwood and Coxwell became known as a “Little Britain”.

The Creek still flowed and Queensvale was still soggy. The H on the map at left is the Duke of York Hotel. Hastings still does not reach Gerrard although it is built up. The little black dots are houses. Where there is red, it means that the area is solidly built up with blocks of buildings. Hastings Creek is the creek on the right where it says “YARDS”. Greenwood and Gerrard is where the “300” is in red. The “C” marks the Holy Blossom Cemetery just to the south of the Maddy Eckler Community Centre at Pape and Gerrard.

There are bridges at Queen west of Laing and on Gerrard east of Hastings over Hastings Creek. There are no Alton Avenue and no Hiltz Avenue but Meen & Meen had great dreams of Queensvale.

Once more, Meen & Meen take some liberties with the truth. “Wilton Avnue is at the present time being extended directly through the property” is simply not true” and the Gerrard streetcar crossed where Alton would be — but at a 20 to 30 foot cliff face.

None the less, some saw a future in Queensvale. Some of the builders were:

- Jacob Kritzer (who moved onto Alton Avenue)

- A. Hill

- M. Crocker

- Hale and McMaster

- A. Moss

- Livingstone

- And J. Kerr

Houses would cost from $3,500 to $4,000. They planned on starting construction in spring, 1914. The Subdivision on Alton was developed as Plan 381 filed in the office of the Land Tiles at Toronto.

April 16, 1914

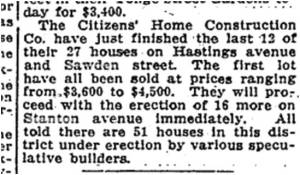

Citizens’ Home Construction Co. built 27 houses on Hastings and Sawden and 16 more on Stanton in the spring of 1914. Another 11 houses were underway for a total of 51 houses in that part of the Queensvale subdivision.

Meen & Meen advertised that Queensvale was:

The cheapest good building land within the city limits.

On April 22, 1914, Meen reported that E. M. Croker (Crocker) had sold one Alton Avenue house to a Mrs. Foulston. Elk Realty Co. had sold 100 feet on Alton Avenue to builders Morrison and Kingborn.

On May 9, 1914 the City of Toronto announced that it intended to extend Hastings Avenue from Doel (Dundas Street) to Gerrard. This would have completed the street all the way from Queen to the railway line north of Gerrard. Sawden, Sproatt (renamed Parkfield east of Leslie) and Stanton home owners were expected to pay part of the costs.

April 22, 1914

On May 22, 1914 Meen and Meen reported that they had sold 300 feet of small lots on Alton Avenue north of Queen for $14,100.

As well Meen and Meen acted as agents for the property immediately east of their Queensvale subdivision on Alton. In 1914 new streets Dorothy and Hiltz were built but had no houses on them. Alton Avenue had already been built. By April, 1914 40 pairs of houses were being built on Alton Avenue and most of the lots had been sold.

On Saturday, May 23, 1914, the Motordrome, a quarter-mile board track raceway opened. It lay between the two Meen & Meen subdivisions: Alton on the west and Hiltz on the East, making for a very, noisy smelly situation. House sales and prces on Alton would be negatively impacted for several years after the Motordrome was closed. On good nights 10,000 or more people would crowd in along Dorothy Street, through a tunnel in the wooden saucer and take their seats to watch races. 1,000 candlepower nitrogen bulbs flood lit the racetrack. Motorcycles roared far into the summer nights, two to three nights a week all summer. In the winter, the owners built a skating rink inside the wooden oval and live bands played late into the night. However, to the relief of those on Alton Avenue, by the fall of 1915 the Motordrome Company was bankrupt. It closed its doors and workers tore the huge wooden saucer down. The wet soggy ground where it had sat stayed a vacant lot until the late 1940s. Where the Motordrome used to be there are now two apartment buildings. Greenwood Court at 1328 to 1338 Queen Street East is a Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) building. It was built after World War Two as housing for returning veterans. See

http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/dfrp-rbif/pn-nb/73012-eng.aspx

The northern building, 1615 Dundas Street East, is a Toronto Community Housing Project. See

http://www.rpei.ca/taxonomy/term/188/all?page=19

For more about the Motordrome, please see my page “Devil wagons and the Murderdrome” on this website.

In the summer and fall of 1914, City of Toronto crews laid sewers, water mains and concrete sidewalks on Alton Avenue. This was the infrastructure the street needed to support housing development. In the fall of 1914 the Bell Telephone Company also worked on Alton Avenue to Doel (Dundas) so that they could install telephone poles and wires on the west side of the street. This was one of the first streets in the neighbourhood to be built wired for phones.

The men of the street, like George Southam of 45 Alton, enlisted to go overseas and fight in Belgium and France. Life was precarious not just for soldiers but for the very young too. Infant mortality was still high. On Feb. 24, 1916, for example, little baby Ralph Townley of 116 Alton Avenue died. He was only four months old.

By 1917 the east side of Alton Avenue had less than a dozen houses on it, some near Queen and some near Doel (Dundas) with a big gap between 49 Alton and 89 Alton. From 48 Alton there are houses solidly to just north of Sawden by 1917 although some were under construction. There were no houses from 48 Alton to Queen. This is not surprising as this is where Hastings Creek flowing diagonally across Alton Avenue to Queen Street. The houses on the west south of 48 Alton and on the east between 49 and 89 Alton could not be built until the Creek was put underground.

While builders were putting their homes up, war was tearing the families in those houses apart. The East End casualties were among the highest of any Canadian neighbourhood in World War One. Alton Avenue was no exception. I have chosen just several examples of many from this street. I am old enough to remember veterans from the Great War and I listened intently to their stories of the trenches. They played cribbage in our kitchen with my Dad while I sat in the corner by the coal stove. I was an invisible little girl, listening to stories of rotting hands poking out of trench walls, of endless shelling and horrible grey-green clouds of gas rolling across No-Man’s-Land. The men forgot I was there, but I haven’t forgotten them.

Canada has a Virtual War Memorial on line. To search this go to:

http://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/memorials/canadian-virtual-war-memorial

Toronto Star, May 9, 1917

Pte. George Alexander Riddell died on May 9, 1917. His brother was killed in action on October 25, 1916. Their brother John survived the war.

In early October, 1917, four, perhaps not completely sober, occupants of a car were nearly killed closer to home.

Riverdale, Oct. 3 – One dark night an auto, with two ladies and two gentlemen aboard, came speeding down Prust avenue on to Gerrard street. Unfamiliar with the locality and seeing the street lights glimmering southward across the Greenwood flats, the driver steered straight ahead, believing the street continued in that direction. When he finally realized his mistake and swung his car sideways, he was half way down a hole 20 feet deep, just south of Gerrard. From midnight until morning, in a ceaseless rain, the chauffeur and the police stood guard over his property. Finally a big truck was secured to haul it back to safety, bending an axle in the process.

(Toronto Star, Oct. 3, 1917)

Accident after accident occurred at that spot on Gerrard. This is perhaps the most dramatic argument for extending Alton Avenue through to Gerrard despite the cost.

Meanwhile sales were not going as well as expected. The Motordrome had dragged the street’s reputation down. Meen & Meen’s statement that it was only 15 minutes on the streetcar to King and Yonge was probably another example of exaggeration in the name of sales.

$2,500 – REDUCED FROM Thirty-three hundred, Alton avenue, brick semi-detached, six good rooms, three-piece bath, good furnace, gas and electric, mantel, balcony, rear porch, side entrance. Five hundred cash, fifteen minutes on cars from King and Yonge Sts.

(Toronto Star, Nov. 19, 1917)

In 1918 there was still a big gap on the east side of Alton Avenue from 49 (Charles Smith) to 89 (Edward Marriott) just as there was from Queen Street to Numbers 48 and 50 which were vacant. Nothing much had changed in a year, at least on the surface.

$3,450 – CHEAPER TO BUY THAN pay rent. Best construction, solid brick, eight rooms, almost new, newly decorated throughout, two mantels, laundry, stone foundation, all latest improvements, Alton avenue, close King cars.

(Toronto Star, Feb. 25, 1918)

Look at the upper right hand corner to get an idea of how deep the Devil’s Hollow was at the top of Alton Avenue. We are looking east towards Prust and Alton Avenue. They reach Gerrard at the top of the hill in the distance. Note the bridge over Hastings Creek. No houses were built between Hastings and Prust or Alton until the Creek was buried.

Looking south-east towards Alton Avenue in the distance, along the ravine of Hastings Creek. The backs of the houses on the north side of Stanton are clearly visible in the middle behind the lamp-post and the boy with a white shirt and tie and the man with the umbrella and brief case. The houses on the right are on the east side of Hastings Avenue and are still there, quite recognizable.

Looking south-east towards Alton Avenue in the distance, along the ravine of Hastings Creek. The backs of the houses on the north side of Stanton are clearly visible in the middle behind the lamp-post and the boy with a white shirt and tie and the man with the umbrella and brief case. The houses on the right are on the east side of Hastings Avenue and are still there, quite recognizable.

In 1918 just as the Great War was coming to an end, one of the most deadly pandemics the world has ever known struck, taking the young and healthy while leaving the elderly — the opposite of what influenza usually does. Older people had some immunity to the virus that caused what was known as “The Spanish Flu”; young people had none. These are some of those who died on Alton Avenue; there may be more. Aletha M. Payne died of heart failure at the age of 22 from influenza which caused pneumonia. She had been sick 10 days before she died. Another death on Alton, Minnie Lennard, aged 27, ill seven days. She was a servant from London, England. Florence C. H. Gardiner, 25, 80 Alton Avenue, sick 7 days. Alton doesn’t seem to have changed much on the surface by 1919, but a World War and an influenza pandemic must have changed everything.

$3,100 – ALTON AVENUE, SOLID brick, six rooms, through hall, mantel.

(Toronto Star, Oct. 19, 1918)

Monarch Realty had bought most of the Russell Estate for $115,000 in 1912. In 1913 it sold the property to Meen & Meen for $155,000. In 1919 Meen & Meen went out of business. Benjamin Meen, stock broker and realtor, had enlisted, but was in no shape for business when he came back from overseas. He went to the trenches as an officer in the Queen’s Own Rifles and was badly wounded. (His business partner was his brother John Meen.) Witthout Meen & Meen, the Queensvale property passed back to Monarch Realty. Monarch Realty built 11 detached houses on Doel (Dundas) near Alton, in the spring of 1919 just as the troops were trickling back from Europe and a housing shortage began.

Donald McCuish, 156 Alton Avenue, returned on the Baltic, May 8, 1919. Born Aug. 17, 1893 in Edinburgh, Scotland. He was a butcher. His next-of-kin was his mother Elizabeth McCuish. Private G. P. Pine, 18 Alton Ave., returned on the Caronia, 1919. Another soldier returns, G. Burke, 86 Alton Avenue, on the Metagama. And more and more came home.

$3,300 – 89 ALTON AVENUE, Bargain, solid brick, six rooms, every convenience, easy payments.

(Toronto Star, Aug. 2, 1919)

The telephone was a positive draw for those seeking to rent a flat or rooms, just as Internet service is today.

2 UNFURNISHED ROOMS AND Balcony, all conveniences, use of phone. Gerrard 2770. 150 Alton avenue.

(Toronto Star, Aug. 26, 1919)

Dogs were big news on Alton Avenue just as they are today with the busy dog park at the south-west corner of Greenwood Park.

COLLIE DOG WINNERS

Judging at C.N.E.

“Bellfield Bucklyvie,” owned by Donaldson and Gray, 47 Alton avenue, captured the breeders dogs, and color class.

Parks Commissioner Chambers was pushing hard to get Greenwood Park approved by City Council. Mayor Thomas Church was firmly against this, as were some other Council members who objected to spending money on the East End and who felt that parks for working class families would encourage the men to loaf around.

CITY TO GET NEW PARK AT COST OF $125,000

Fourteen Acres near Alton Avenue Proposed for Purchase.

The city will get a new park, which will probably be used as an athletic field, if the recommendations of the Assessment Commissioner, which will come before the Parks and Exhibition Committee to-morrow, is finally adopted by the City Council. The commissioner has recommended the purchase from the Monarch Realty Company of 13.67 acres east of Alton avenue, south of Gerrard street, formerly the site of a brick yard, at a cost of $125,000.

(Toronto Star, Sept. 15, 1919)

It is only a dump – a hole in the ground. The earth has been taken out for brick-making. It will cost $100,000 to fill in. Alderman Baker

Before Greenwood Park was created, Sproatt Avenue extended through Greenwood Park and there were two new streets as well: Glen Dhu Road and Earlham Road. They can be seen on some maps. Glen Dhu is a valley and sea loch in north-western Scotland. It also sounds better than “The Devil’s Hole.”

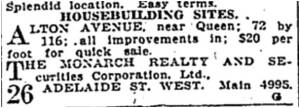

The “adjoining park” is more spin. The park had not been built yet.

Local men and boys (and a few girls) used a corner of the abandoned brick quarry as a baseball diamond, as empty lots were often used. People called on the City to buy that land to make a park since there were no parks in the neighbourhood. Parks Commissioner Charles Chambers wanted to oblige. Mayor Thomas (Tommy) Church opposed this new park, clearly feeling the money could and should be spent elsewhere than on a large park for the East End. Mayor Church and Park Commissioner Chambers were locked into a hot-worded rivalry. The Commissioner wanted to issue debentures to raise money for Parks, including the athletic field on Greenwood Avenue and Willowvale Park (now Christie Pits). The Mayor felt that the $650,000 could be spent better elsewhere than on parks for poorer people. He did not want to see the mill rate go up to pay for playgrounds and athletic fields. “…the present was no time for purchasing parks and some which had been bought were nothing but brick yards.” (Toronto World, Oct. 29, 1919)

One local hit back in a Letter to the Editor:

Mayor Church for some reason or other seems “dead set” against giving the residents in the neighborhood of Greenwood avenue a playground and apparently the only thing he is able to say against it is that it’s “an old brickyard.” I fail to see why in the world this enters into the question at all—would his Worship desire to have it remain so or would it be to the interest of the city at large to have the spot improved and at the same time prove a great benefit to the health and welfare of the community. Look out, Mr. Mayor. Your treatment of the East End in this matter is very poorly camouflaged by “economy” talk at this time. The East End is coming into its own. EAST ENDER

(Toronto Star, Nov. 1, 1919)

Some City Hall opponents fought tenaciously to prevent Greenwood Park from happening, arguing that the City was paying too much money , hinting that the City was getting “ripped off”. E. Murphy , the President of Monarch realty, denied offering the Greenwood Park property to Lewis M. Wood for only $70,000 during the war.

While the park issue was taking up some media attention, another story caught the sympathy of dog owners.

On March 7th, champion collie, Alstead Aeroplane, went missing from his new home on Alton Avenue. In December he was found roaming in High Park.

www.chelsea-collies.com/alstead.html

accessed Feb. 26, 2016

Photo from http://www.pedigreedatabase.com accessed Feb. 26, 2016

C. H. Macdonald,

Toronto at a Glance,

1920

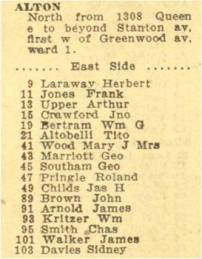

In this 1920 map, Stanton, Sproatt, Glen Dhu and Earlham are shown where Greenwood Park is – even though they did not exist there. Alton his shown now as continuing all the way up to Queen while Hastings has not yet been extended to Doel (Dundas). Hiltz does not yet reach either Doel (Dundas) or Queen but can only be reached by Dorothy.

Might Directories’ 1920 official street guides of the City of Toronto and suburbs

Might’s map shows Glen Dhu, Sproatt, Stanton and Earlham where Greenwood Park was being created. It also shows Doel Avenue as continuous through Greenwood (which it wasn’t). Hiltz and Dorothy are not shown.

In these photos Alton Avenue runs horizontally across the photo from left to right . Sawden is the street running westward towards the Leslie Street School in the distance. On the right is Parkfield (then known as Sproatt).

City of Toronto Archives. Series 372, s0372_ss0052_it0805

Alton Avenue a few days later. The spires in the distance are St. Joseph’s Church and School which was then just north of Doel (Dundas) on the east side of Curzon. Both were torn down many years ago.

This photo from June 7, 1920, shows children playing in the make-shift baseball diamond at the north-east corner of the brick pit between Greenwood and Alton. The City of Toronto has not begun work here yet.

Toronto World, July 1, 1920

July 3, 1920, Greenwood Opening

Mayor Tommy Church, with his straw hat in hand, while Parks Commissioner Charles E. Chambers tosses the coin to decide which team will go to bat first: the Simcoes on the left or the Classics on the right. In a few minutes a classic Toronto thunderstorm broke, drenching everyone including the Mayor who loathed the idea of Greenwood Park. The Park was now complete and Alton Avenue’s day was about to come.

This 1921 map shows that Hastings Creek has now been buried in the sewer system. The ravine on lower Alton has been filled in and Hiltz has been laid out. The dashed lines indicate streets that are planned but not built. A lattice of streets occupies Greenwood Park but none have been built or would be built now that the Park was open. Doel is a dashed line between Alton and Greenwood and east of Greenwood as well. Dundas Street will not be built until the 1950s. Government of Canada topographical maps and City Engineering maps are the most accurate that I have found. Many maps show streets that only existed in a realtor’s or planner’s mind.

Now that the “Devil’s Hole” is tamed, Monarch Realty wants to sell those lots fast.

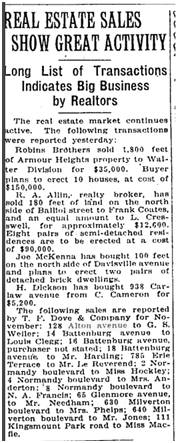

In 1921 and 1922 newer-style bungalows, mostly detached or duplexes, filled in the empty lots on Alton. Builders put up most of the newer houses in the spring of 1922. Back then real estate companies aimed to have their houses on the market by the long weekend near the end of May. Victoria Day was the traditional day for real estate open houses.

Things were looking good. A beautiful park was near by. The street was improved. Alton now reached Gerrard. That part of the ravine, so hazardous to unwary drivers, has also been filled in. The Devil’s Hollow was now the much shallower Devil’s Dip, the monster buried.

In 1922 The Monarch Realty Company dissolved having developed Alton, Hiltz, Dorothy, Sawden, Parkfield, and Stanton as well as many other parts of the old East End. It also was active in other Toronto neighbourhoods.

1923 Changes in Street Names Come Before City Council

Toronto has one thing in common with post-war Europe—its map is continually changing. City Council on Monday will have before it a by-law to authorize changes in the names of several streets. This will undoubtedly be passed and the following changes will come into effect …Morley avenue to Woodfield road, Alton street to Alton Avenue.

(Globe, January 20, 1923)

In 1923 “Alton Street” officially became “Alton Avenue” which is the name local people had been using since 1913 as well as the real estate agents.

In this map from the 1924 Goad’s Atlas, Alton Avenue has taken the form that it has to this day. Neat rows of duplexes and some single family homes line both sides of Alton’s south end. North of what will become Dundas, brick homes line the west side of the street. Earlham Road was part of the Greenwood Park of the day. The houses on the west side of Greenwood were expropriated later and that area incorporated into the park along with some other buildings.

March 1, 1928 Details from a larger photo. City of Toronto Archives. Series 372, s0372_ss0001_it0764

Remembering Our Fallen

THREE names on the Honour Roll are of firefighters that died at the En-Ar-Co boat explosion on July 23, 1934. Another FOUR names were added from deaths subsequently attributed to the disaster. Sadly, some of those that perished were working for other firefighters that were attending an annual family picnic in Niagra Falls.

From

For more information about the Enarco disaster read:

Robert Kirkpatrick. Their Last Alarm: Honouring Ontario’s Firefighters. General Store Publishing House, 2002.

Toronto Star, Sept. 15, 1934

By Unknown

http://www.naval-museum.mb.ca/battle_atlantic/ottawa/hmcs%20ottawa%20photos.htm

HMCS OTTAWA began life in 1931 as HMS CRUSADER before her commissioning into the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) on the 15th of June 1938 in Chatham, England. Originally stationed on the west coast, OTTAWA was transferred to Halifax, Nova Scotia following the outbreak of the Second World War where she escorted convoys between Great Britain and Canada.

In the first year of the war, OTTAWA conducted convoy escort duties in the western Atlantic. In the fall of 1940, OTTAWA deployed to Scotland to assist in local escort operations until her return to Canada in the spring of 1941. OTTAWA then joined the Newfoundland Escort Force where she continued her service off the coast of Newfoundland until her loss 15 months later.

On September 13th 1942, 500 nautical miles east of St. John’s, Newfoundland, OTTAWA was torpedoed. Less than 30 minutes later, unable to maneuver, she was hit a second time. This time the torpedo broke her in half, sinking her. Only 65 survivors were rescued from the freezing Atlantic waters.

http://www.naval-museum.mb.ca/battle_atlantic/ottawa/

Toronto Star, Aug. 21, 1985

Below from Google: the Meen & Meen office at the corner of Alton and Queen.

https://www.google.ca/maps/@43.6637769,-79.3279252,3a,75y,18.98h,89.41t/data=!3m7!1e1!3m5!1stysUOhVmi41ytDU6JWpeiw!2e0!6s%2F%2Fgeo2.ggpht.com%2Fcbk%3Fpanoid%3DtysUOhVmi41ytDU6JWpeiw%26output%3Dthumbnail%26cb_client%3Dsearch.TACTILE.gps%26thumb%3D2%26w%3D392%26h%3D106%26yaw%3D72.8617%26pitch%3D0!7i13312!8i6656?hl=en