An interesting house from the outside, the Isaac Price House at 216 Greenwood is even more interesting in ways we cannot imagine as threads of history run through it, weaving into a larger tapestry that includes the Underground Railroad.

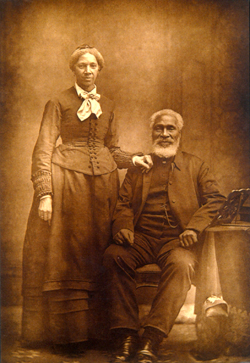

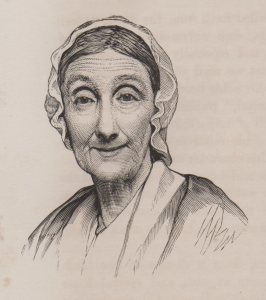

Isaac Price and Annie Margaret Price (nee Simpson) Toronto Star, Jan. 4, 1930

Isaac Price (Ike to his friends) was born on November 18, 1854 in Bridgwater, Somerset, England, into a family where the brickmaking trade was passed down through generations. John Price was the first brother to come to Canada, arriving in 1864, followed shortly by the rest of the family and many others from Bridgwater.

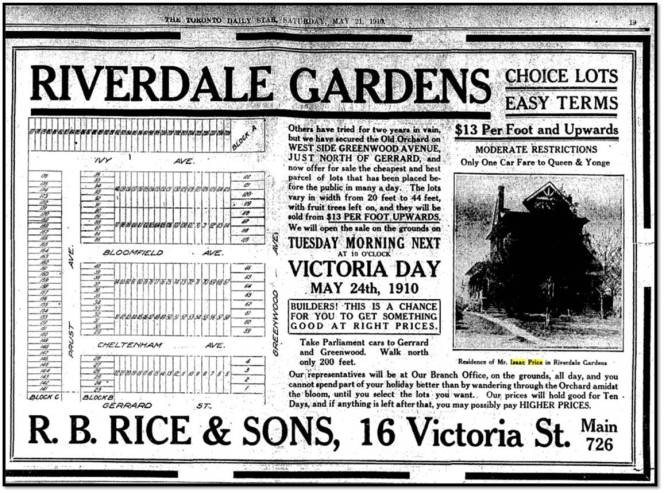

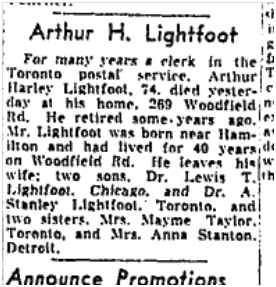

This large brick villa showcases the Price skill and their products. It is featured on this advertisement for Riverdale Gardens, the subdivision from Prust to Greenwood, north of Gerrard. William Prust (1847-1927), an English shoemaker turned carpenter and contractor, lived on the west side of Greenwood just north of Annie and Isaac Price. The area was then an old orchard. Prust wanted to save the trees as much as he could and it was a positive selling point. The real estate agents claimed that every new home had a fruit tree in the yard. (Toronto Star, May 21, 1910). Most of the people moving into the new area were immigrants from Britain, but not all. Men and women, like Luella Price on Redwood Avenue and the Lightfoots on Morley Avenue (now Woodfield Road) were the descendents of those who had lived under slavery. Some had come up the Underground Railroad to Canada and stayed after slavery ended.

The builder of 216 Greenwood Avenue, Isaac Price, had a strong connection to abolitionism. In a BBC interview, March 23, 2007, historian Roger Evans described how the town of Bridgwater, Somerset, England, the original home to the Prices and many other brickmakers along Greenwood Avenue, became so firmly set against slavery.

Slavery by the British began in the mid-17th century. By 1685, at the time of the Monmouth Rebellion, it was in full swing.

After the Battle of Sedgemoor and the ensuing Bloody Assizes, when hundreds were hung, drawn and quartered, the King granted permission for convicted rebels to be taken into slavery.

With hundreds of Somerset men being transported, local feeling against slavery ran high. These were not the wealthy landowners, but yeoman of strong religious convictions, condemned into slavery.

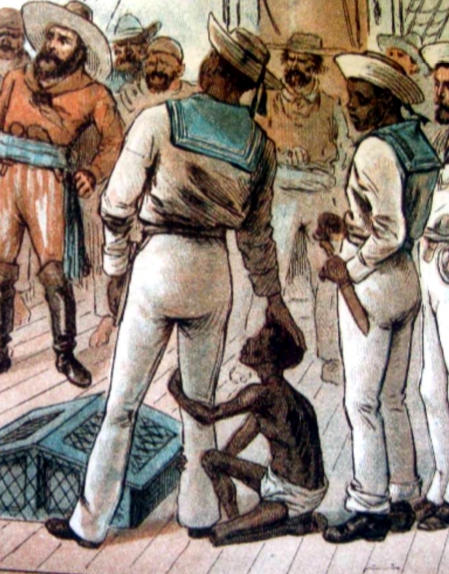

In total, 612 Somerset men were transported into slavery. They sailed in eight ships to the West Indies.

Many died during the voyage. Some died on the quayside awaiting their auction.

Within four years, the survivors were granted free pardons but most lacked the fare home.

Those who returned told their families and communities of life as a slave.

In 1785 the men and women of Bridgwater, Somerset, sent a petition to Parliament calling for the abolition of the slave trade. Parliament did nothing, until 1807 when it outlawed British involvement in the slave trade. Bridgwater was the first British town to ask the Crown to do away with slavery.

See more at: go to http://www.bbc.co.uk/somerset/content/articles/2007/02/19/abolition_somerset_and_slavery_feature.shtml

The white man’s happiness cannot be purchased by the black man’s misery.

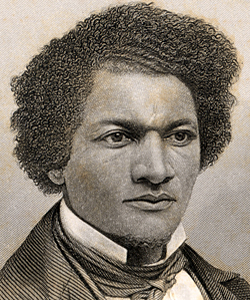

Britain’s involvement in the slave trade may have over and done with, but slavery was still going strong in America. Frederick Douglass, disguised as a “Black Jack” or free black sailor, escaped slavery and reached New York City. His became one of the strongest voices against slavery. Abraham Lincoln encouraged him to travel on tours in the United States but also in Canada and Europe. Douglass’ eloquent speeches helped build the abolition movement. He spoke in Bridgwater, Somerset on August 31, 1846 and asked his receptive audience to do everything they could to end slavery. The people of Bridgwater drew up another petition but this time they sent it to the town of Bridgewater, Massachusetts, asking the citizens to twin with them to fight slavery. More than 1,200 men and women of Bridgwater, England, signed that petition, ordinary men and women. Among them were a number of Prices, including the parents of Isaac and John Price and their other brothers, well known Leslieville brick manufacturers.

They came to a Leslieville that had a tradition of welcoming refugees who had escaped slavery.

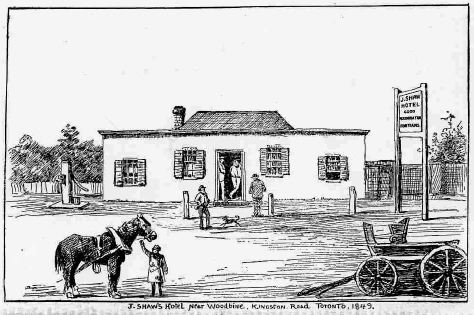

Some of the first black residents appeared in the 1830s in what was to become Leslieville. Around 1834 or 1835, an English settler named Charles Watkins built a tavern near the northwest corner of Boston Avenue and Queen Street East. Watkins liked farming more than running an inn so he rented the inn out. The first landlord, Sandy Watson, kept the inn until about 1847. Then James Shaw rented the place and it became known as Shaw’s Hotel. It was one of the first taverns in Leslieville. According to John Ross Robertson: Mr. Shaw was very fond of horses, and it was one of the sights of the neighbourhood to see the black hostler, an old escaped slave known as ‘Doc’, trot out Mr. Shaw’s team to water every morning. (John Ross Robertson , Landmarks, Vol. III, p. 320.) “Doc” was Lewis Doherty (or Dockerty), an American who escaped here with his family. The picture below shows Lewis Doherty holding a horse in front of Shaw’s Hotel (northwest corner of Queen Street and Boston Avenue). Descendents of Lewis Dockerty would continue the family tradition of being “horse whisperers”.

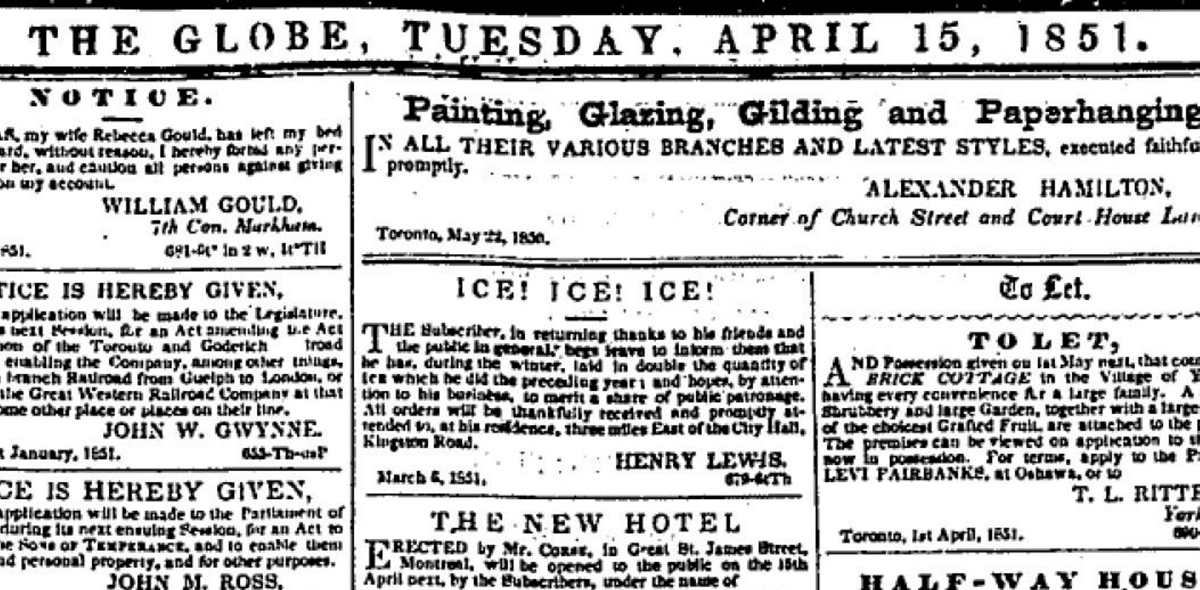

George Brown, with the Globe newspaper (now the Globe and Mail), with his father and brothers were leaders in the fight against slavery. George Leslie and George Brown were good friends and shared similar “Grit” beliefs.

The extinction of slavery would forever extinguish the slave trade, that scourge of a quarter of the globe, inflicting an amount of misery on the unoffending colored race which no pen can enumerate, and which will never be known on this side of Time. (Globe, Jan. 6 , 1846)

Yet both free blacks and former slaves were subject to racism here: discrimination and even assault. At that time the acceptable term for people of colour was “coloured”; “Negro” was far too close to “n—–” and the Globe objected to the use of “Negro”. (Globe, Jan. 6 , 1846) However, whatever the efforts of white men and women to fight slavery, the black community itself organized effectively both to welcome and support refugees from south of the Mason-Dixon line. The black churches, especially the Baptist and African Methodist Episcopal, organized for the “improvement” of their community.

Many refugees passed into Canada along the Niagara frontier, but also at Windsor and Sarnia. South-western Ontario had substantial communities of African Americans. There were efforts to prevent black people from buying and owning a home wherever they wanted, creating in effect segregated communities, keeping people separate and unequal. Black leaders responded, “such a power we believe to be dangerous to liberty, and if carried into effect would not only deprive us of our civil rights, but would eventually exclude us from settling in any part of Canada.” Col. John Prince of Sandwich (now Windsor) was appalled, stating, “…no person has witnessed with deepest regret than I have the prejudices which unfortunately exist in too many parts of Canada…” (Globe, Oct. 25, 1849). He hoped that with the passage of time the prejudice would die away and that African Canadians would enjoy all the rights and privileges of other Canadians.

Associations like the Elgin Association for the Social and Religious Improvement of the Coloured Population of Canada” formed to assist the refugees, but the Elgin Association also formed a separate community for people of colour where they could prove that black people were “moral and industrious” and worthy of full citizenship and equality. Toronto money and organizers supported this endeavour. (Globe, Nov. 24, 1849)

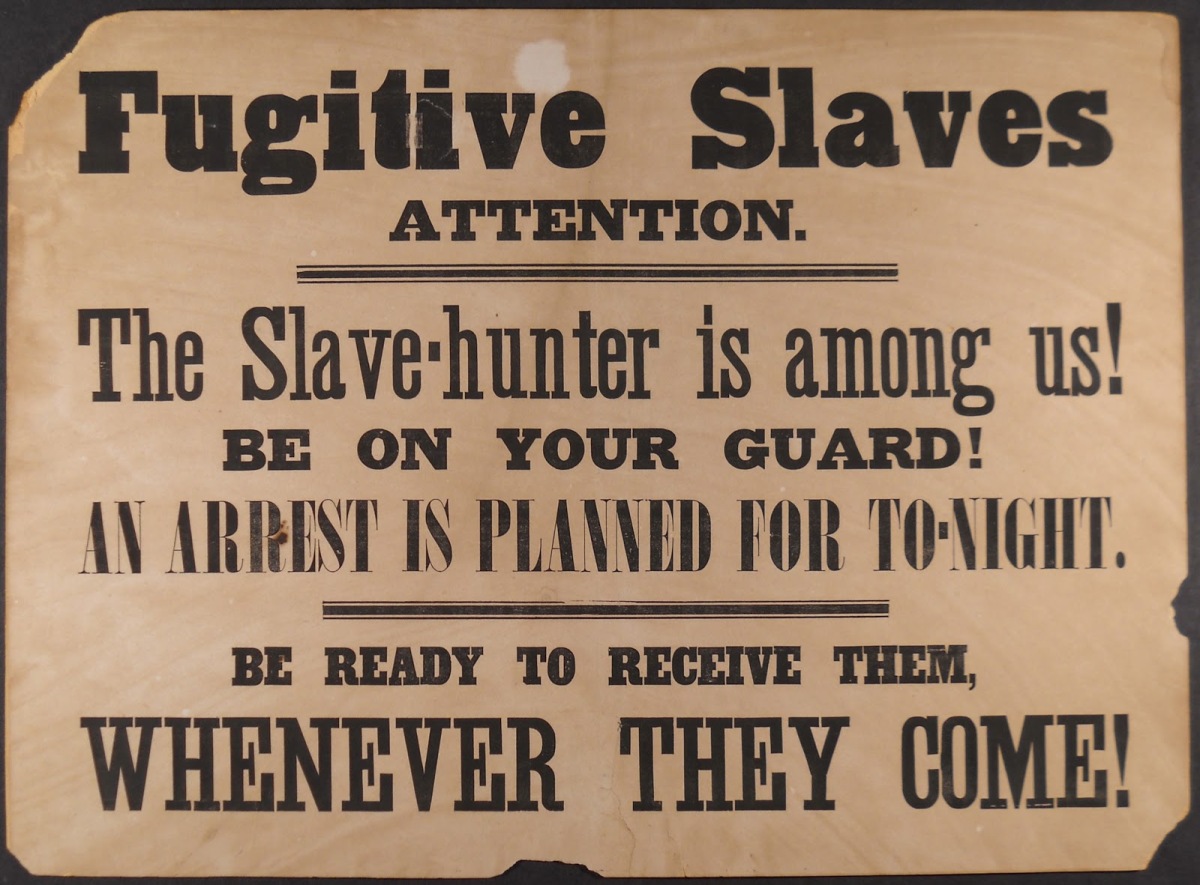

The passage of a law allowing slave catchers to go anywhere in the Northern US to capture refugees created a flood across the border into Ontario. Punitive measures were enacted against those who helped escapees along the Underground Railroad.

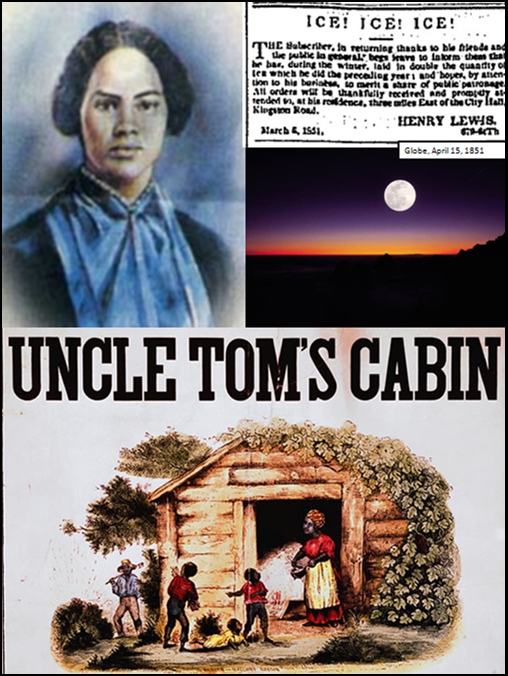

In 1847 George Smith and William Cook, local farmers and brickmakers, opened a tavern at the south east corner of Leslie Street and Queen Street East. George Smith and William Cook were the ex-owners of Shaw’s Hotel (at Boston Avenue and Queen Street East). In 1852 their new venture was named Uncle Tom’s Cabin in what was likely a reference to “Doc” and the bestseller. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s anti-slavery book was originally to have carried the subtitle, The Man that Was a Thing. Uncle Tom’s Cabin or Life Among the Lowly ran in the Era newspaper from June 1851 until April 1852. Uncle Tom‘s Cabin quickly became a smash hit in the USA, Canada and Great Britain. A Montreal monthly periodical, The Maple Leaf, serialized the book, with an abridged conclusion, from July 1852, until the following June. The Globe, owned by George Brown, well-known newspaperman and abolitionist, printed extracts and the whole fifth chapter: Hundreds of young boys who, less than ten years later, would enter the Northern armies, devoured it in the one-volume edition.

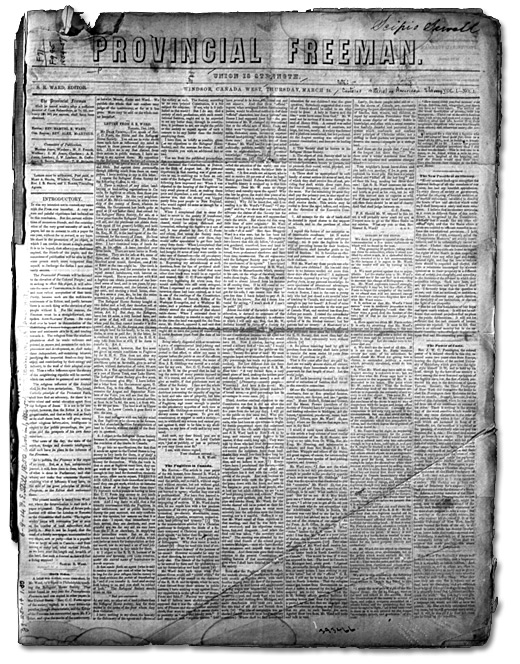

It is likely that the Uncle Tom’s Cabin was used by former black slaves who worked for Thomas Carey and Richard B. Richards, cutting ice on Ashbridge’s Bay. Certainly Henry Lewis, another black businessman, had an ice house on Ashbridge’s Bay. Thomas Carey married Mary Ann Shadd (depicted above) who became the first woman editor of a newspaper in Canada, The Provincial Freeman. Neither lived in this area, but both had a great influence here.

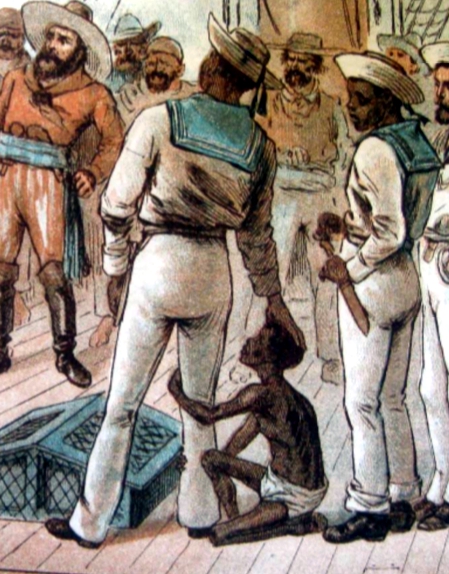

I have found that black sailors stayed at Leslieville hotels, as they did other hotels and taverns on the shores of the Great Lakes. Known as “Black Jacks”, many had been slaves.

There are many refugees who “go down to the lakes in ships, that do business on the great waters;” and these fresh water sailors earn good wages in summer.

No opportunity presented of seeing this class, but the general report about them was that they “loafed around all winter, and spent all their earnings.” This is proof that they do work and earn money; and if they spend it just as other tars do, the fact only proves that the vocation of sailor affects blacks as it does whites. (Charles Twitchell Davis, and Henry Louis Gates, editors. The Slave’s Narrative. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985, p. 121.)

Captain Averill, an experienced sailor, explained why white captains preferred black crews:

Colored men do very well for deck hands, and firemen, and the like of that. They are the best men we have. We have to pay them the same as white men, and I prefer them to some portion of our citizens. We have to keep them separate from white sailors. We cannot mix them. We always carry a black crew or a white one. We will take a crew of firemen, darkies, or a crew of deck hands, darkies. They are fully as good as white sailors, in regard to temperance. We can put more confidence in them than we can in white men. (Samuel Gridley Howe, The Refugees from Slavery in Canada West. Boston: Wright & Potter, 1864, pp. 76-77)

Many Black Jacks were deeply involved in the Underground Railway. At the risk of their lives, they distributed information about escape routes and pamphlets to blacks in southern ports. They also helped fugitives who stowed away on Great Lakes vessels to Canada.

By 1861, about 20 per cent of Leslieville’s population were black men, women and children (1861 Census).

Charles and Elizabeth Johnson lived near the Woodforks (or Woodforths). James and Jane Woodfork were Baptists, the other major denomination among those coming from the US. Their son Henry was born in Canada. Samuel and Susan Wilmore were also Baptist. Their son George was born in the US. Cecil Foster has observed that “[a]s long as there have been Blacks in Canada, there has been a church at the heart of the community” (Cecil Foster, A Place Called Heaven: The Meaning of Being Black in Canada, Harper Collins Publishers: Toronto, p. 54). Samuel Winder was born in the US, but his wife Susan and sons Lewis and Samuel were born in Ontario. They were Baptists too. After his wife died Samuel Winder married Maria Sewell.

The Davis family were Episcopal Methodist. John and Eliza Davis and their children Mary, William, John, Ezekiel and Jane were all born in the USA. Later William Davis became a music teacher, as did his daughter Eva (1891 Census). John and Mary Harmon had two sailor sons, Thomas and Edward. All were Wesleyan Methodists, born in the USA. George and Harriet Wilrous were born in the USA, but their children Sarah, Loreen and Martha were all born in Ontario.

Henry Lewis and his wife Louisa Carey were born in Ontario. Both were Baptists. The black families became closely linked through marriage. Louisa was the daughter of barber Isaac Carey who went into the ice business. Henry also became an ice dealer.

James and Elizabeth Whitley were born in the USA, but their son James was born in 1860 in Ontario. Some we know little about, like Darcy Wright, Aaron Finley, Robert Johnson, Daniel Harris (1861 Census) or William Browne (1871 Census) (sometimes the census keepers just recorded “Negro”). The Chorneys, William Browne and others lived closed to John and Elizabeth Logan which may suggest that these Scots Presbyterians, along with their Wesleyan Methodist neighbours shared George Brown’s hatred of slavery and open attitudes. (It seems that a child of one of these families was named “John Logan” while his brother was “George Washington”.) J. H. and M.A. Colbert, husband and wife, gardeners, also lived near the Logans in the 1851 Census.

Alfred Blackburn lived “across the Don” as did James Mink for a period. Alfred’s brother Thornton Blackburn began the first taxi service in Toronto. James Mink owned a livery stable in downtown Toronto. His wife Eliza was white and there were a number of so-called mixed marriages. Samuel Fitzhue, an African American aged 50 (Methodist), married Ellen, an Englishwoman (Anglican), 20 years younger. (There was a Fitzhue Street in Leslieville in the mid 19th century.) He was a labourer in Leslieville (1871 Census). John French was born in the U.S., but his children Jane and Mary were born in Canada. Their mother seems to have died.

Samuel and Rachel Sewell were gardeners near Logan and Queen. Their farm lane became known as “Sewell’s Lane”, and later “Logan Avenue”. Sons William and Isaac were born in the U.S. Son Samuel was born in Ontario. While Samuel Sewell Sr. claimed to have no religion in the 1851 Census, the rest of the Family was Baptist. Samuel Sewell Sr. was born in 1797 under slavery and died May 8 1873. He could be said to be the patriarch of Leslieville’s black community. He is buried in the Necropolis Cemetery with his family. His wife Rachel died in 1879 and is buried beside him. Son William died early at the age of 15 on Feb. 6, 1856, from scrofula or tuberculosis of the glands of the neck. Daughter Maria Sewell married Samuel Winder (Widower) on Jan. 21, 1847.

Leslieville’s black community in the mid-nineteenth century included P.H. Churney or Cheney, his wife Hannah, and their children Thomas, Augustus, Lora, Mary and Joseph. Like many of the black community they were Episcopal Methodists. Their family was marked by singular tragedy. On July 16, 1860, son William drowned in the Don River while swimming near the King Street bridge. He was only eight. (Globe, July 16, 1860)

While Mrs. Barry was attending William Churney’s funeral, a fire broke out in the provisions store of Henry Barry on Queen Street in Leslieville. A little boy aged four and a girl aged six died in the inferno. Their names were Rachel Barry and Sewell Barry. The Globe newspaper blamed Henry Barry for losing “all control over himself” and not rescuing the children. The fact that the only fire truck had to come all the way from near Parliament and King must have played a factory in the total destruction of the one story wooden building. There was also no water available to fight the fire. Being July and hot, the wells may have been dry. “An old coloured woman”…”somewhat addicted to liquor” was blamed for starting the fire.

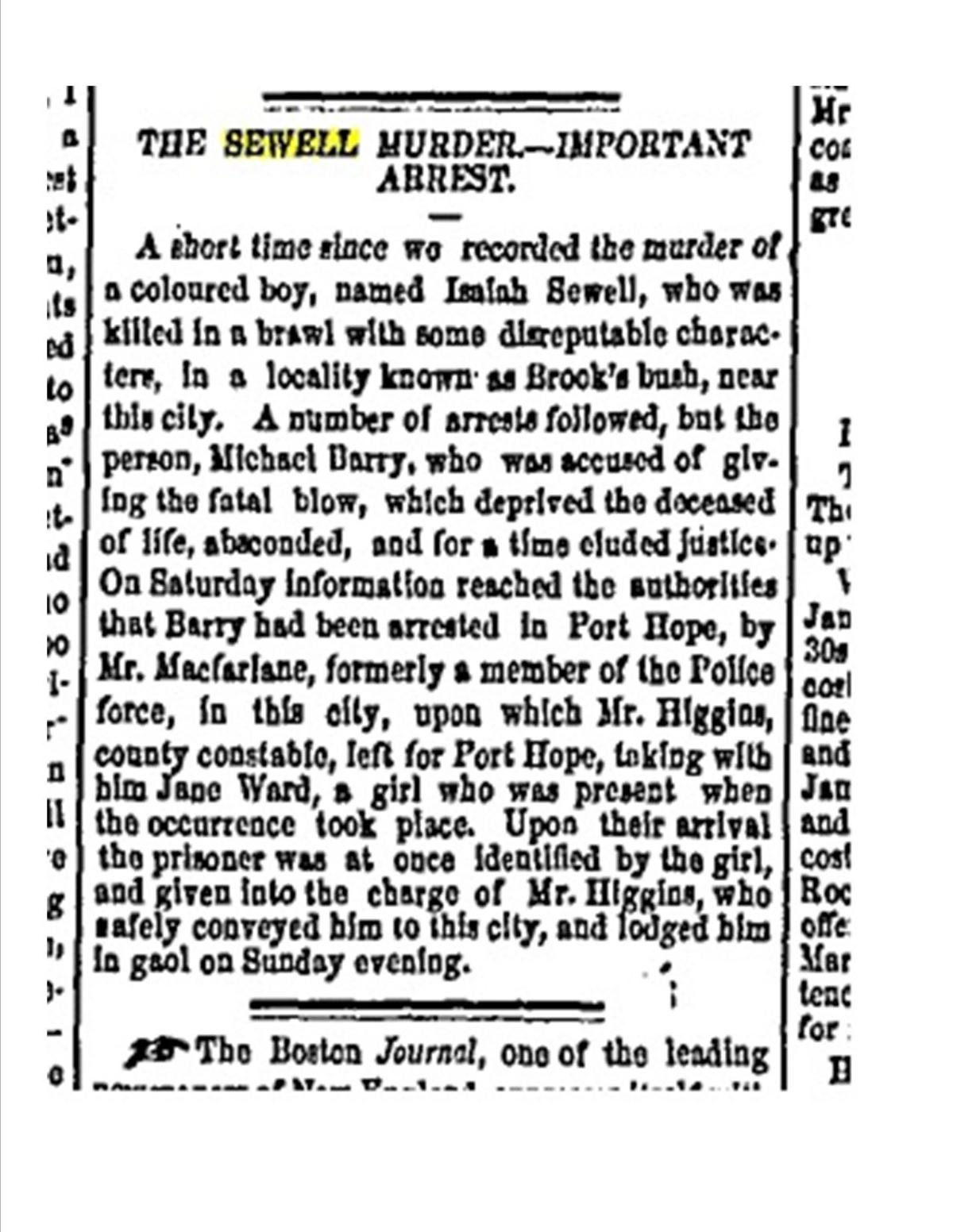

On July 21, 1856 Michael Barry (no relation to the black Barry family) and others of the Brook’s Bush gang murdered Isaiah Sewell by bashing him over the head. The Brook’s Bush gang was a collection of prostitutes, pickpockets, thieves and petty criminals whose headquarters was an old barn in what is now Withrow Park. They were all white, mostly Irish but lead by Jane Ward, a vicious English prostitute. Jane Ward, like most of those present, was conveniently looking the other way when Sewell was murdered. A prostitute named Catherine Cogan flirted with Isaiah Sewell. A witness said, “I heard someone say it was a shame for a white girl to be seen with a black man.” Samuel Sewell was a witness in the trial. He had sent his son to the mill road (Broadview Avenue) with money to buy hay. Isaiah was what we would call, “A good kid.” He never associated with the Brook’s Bush gang. It was part of their modus operandi to ply a victim with alcohol and lure him with sex, and then rob him. Another witness testified, “ [Michael Barry] never spoke to the coloured boy. The coloured boy was standing with his back to Barry. Barry never spoke when he struck the blow. The blow was given with a black glass bottle…He fell immediately, never got up, and never spoke…when the blow was struck, Barry called the deceased a black b—g—r…” The money disappeared. Michael Barry was convicted of manslaughter, probably taking the fall for the others as he himself was not a gang member, just a “newbie”. For years the Brook’s Bush gang members boasted of getting away with killing a black man. (Globe, Oct. 30, 1856)

The Sewell family plot in the Necropolis fairly shouts, “Research me! I am one of the most interesting historical sites around.”

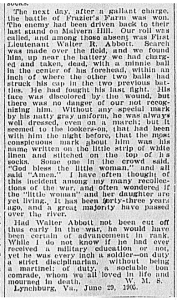

The Barrys lived next to the Bird family, a white family, whose young son, James Bird, died fighting for the Union at the Battle of Chattanooga. Other volunteers from “over the Don” included William Henry Doel (1827-1903), Toronto pharmacist and Justice of the Peace. Like many in this neighbourhood he was a devout Methodist. Another, more famous Canadian, also enlisted. Like them he has an interesting “back story”.

THE ABBOTTS

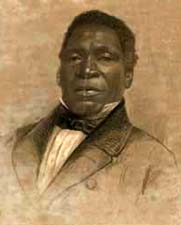

Wilson Ruffin Abbott (1801–1876) was an American free man of colour. Born to a white father and a free woman of colour in Richmond, Virginia, Abbott left home when he was aged 15 to work as a steward on a Mississippi River steamer. He married Ellen Toyer, and moved to Mobile, Alabama. There they opened a grocery store, but left in 1834 after friends warned them that hostile white Alabamans were going to attack their business. Forced to leave Mobile by the animosity and threat of violence, the Abbotts went north to Toronto in 1835.

Wilson Ruffin Abbott fought for the Crown in the 1837 Upper Canadian Rebellion. In 1838, he and others established the Colored Wesleyan Methodist Church of Toronto. He was prominent in the Anti-Slavery Society of Canada and elected as an Alderman for St. Patrick’s Ward on Toronto City Council. He was also a member of the Reform Central Committee. In 1840 Ellen Toyer Abbot organized the Queen Victoria Benevolent Society to help poor black women. She was known for her work for the British Methodist Episcopal Church.

According to Catherine Slaney, in Family Secrets: Crossing the Colour Line, (page 214), Josiah Bartlett Abbott (1793-1849) and Anne Wilson may have been Wilson Abbott’s father and mother. The Abbotts were a prominent New England family and Josiah was born in Connecticut. The couple married in Salem, New Jersey, but their faith, the Salem Society of Friend meeting, turned them away. (The Friends were also known as the Quakers.) They sold their farm and moved to Richmond, Virginia. In Richmond Josiah Bartlett Abbott began buying slaves. One of these women may also have been Wilson Abbott’s mother, but we do know that whoever she was, his mother was a “free woman of colour”.

Ironically, the very Quaker meeting in Salem, New Jersey, that rejected Josiah Bartlett Abbott and Anne Wilson became deeply involved in the Underground Railroad. The Goodwin sisters, Abigail (1793-1867) and Elizabeth (1789-1860), were conductors on the Underground Railroad and their house was a stop on a major route to freedom. Their home is the first New Jersey site to be accepted into the National Park Service’s National Underground railroad Network to Freedom Program. The Underground Railroad, painted by Charles T. Webber, shows Quaker women like the Goodwin sisters at work.

While many escaped up the Underground Railroad with the help of white people, including Quakers, most Conductors were black like the famous Josiah Henson and Harriet Tubman. Yet most fugitive slaves made their way north with no one’s help but their own two feet and the North Star — and those who escaped with them. You can read Josiah Henson’s autobiography,

The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave,

Now an Inhabitant of Canada,

as Narrated by Himself

on line at:

http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/henson49/henson49.html

Josiah Bartlett Abbot, owner of High Meadow in Henrico County, Virginia (just outside Richmond), a former hatter, became a prominent lawyer and financier. He was also the publisher of the Richmond Whig newspaper.

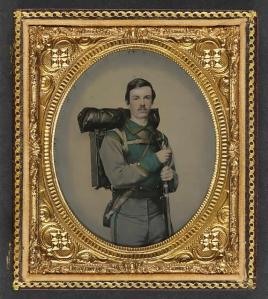

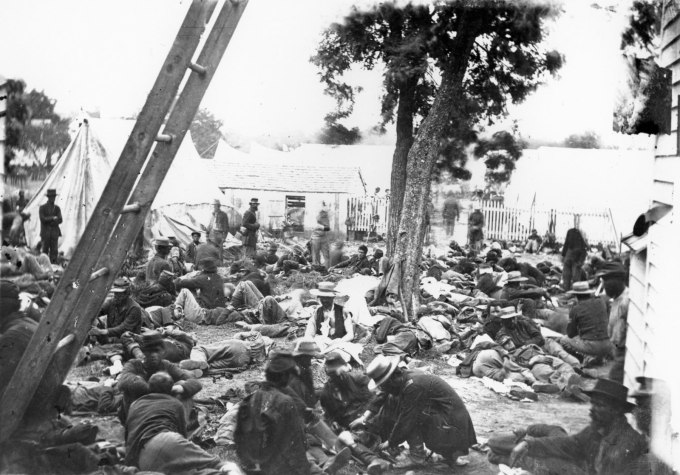

His son Lieutenant Walter Randolph Abbott (1838-1862) was killed in the battle known as Glendale to the Union soldiers and Frayser’s Farm to the Confederates. The Confederates, under General Longstreet, repeatedly charged the Union lines, in an effort to capture the Federal artillery. The fighting was incredibly savage. Confederate E. P. Alexander wrote:

No more desperate encounter took place in the war and nowhere else, to my knowledge, so much actual personal fighting with bayonet and butt of gun.

A Union bullet struck Walter Randolph Abbott in the head, killing him instantly, but “his natty gray uniform” was still impeccable. His wife had sewn his name on a strip of white cloth into the tops of socks, making his body identifiable on the battlefield (dog tags were not invented yet). The Union Army lose about 2,800 men but the Confederates lost 3,600. Both sides claimed it as a victory.

See more at: go to

http://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/civil_war_series/21/sec6.htm

While the Civil War was raging south of the border, Wilson Abbot was becoming a realtor, succeeding as a businessman in Toronto. By 1871 Wilson about owned 42 houses, 5 vacant lots and a warehouse. “With his wealth he was able to purchase the freedom of a number of escaped slaves, to keep his wife’s sister as a well-paid housekeeper, and to engage extensively in community affairs.” (Everett Jenkins, Pan-African Chronology II, p. 126).

See more at:

http://www.blackpast.org/perspectives/african-americans-medicine-civil-war-era#sthash.fdceXmrD.dpuf

Alonzo Chappel, 1828-1887

Oil on canvas, 52 x 98 in.

Chicago History Museum purchase

1971.177, ICHi-52425 – See more at: http://www.civilwarinart.org/items/show/49#sthash.ZM7woJZS.dpuf

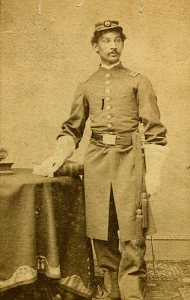

His son, Anderson Ruffin Abbott, was the first Canadian born African American surgeon. During the Civil War, he was one of the only eight black doctors involved with the Union Army, serving from 1863 to 1866. When he enlisted in 1863, the Union Army appointed Abbot as an acting assistant surgeon. This was before he got his medical degree although he did have a medical license. Dr. Abbott worked at the Contraband Hospital in Washington during the war and knew Abraham Lincoln well. He was one of the carefully chosen who were in the room, standing vigil, while Lincoln was dying. He is in the Alonzo Chappel painting below, but it takes a keen eye to find him. Later Mary Todd Lincoln gave Dr. Abbott with a shawl her husband had worn to the President’s first inauguration.

In 1866, after the war finished, Abbott returned to Toronto where, to supplement his medical license, he received a medical degree from the Toronto College of Medicine in 1867. Abbott practiced in Ontario until his death in 1913.

See more about Anderson Ruffin Abbott at:

http://www.blackpast.org/perspectives/african-americans-medicine-civil-war-era#sthash.fdceXmrD.dpuf

and

http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/abbott_anderson_ruffin_14E.html

It is hard to imagine the carnage that Anderson Ruffin Abbott, William Henry Doel and other medical men and women had to deal with in the Civil War.

Men from Bridgwater travelled even further to enlist to fight for the freedom of black Americans. Stonemason William Jolley Nicholls is buried in Bridgwater’s Bristol Road cemetery. His family engraved on his tomb: “fought in the American Civil War for the abolition of slavery”. He fought in a number of battles, including the Battle of Mobile Bay, and was wounded.

See more at:

http://www.experiencesomerset.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Nicholls-grave02.jpg

Not all white Canadians were anti-slavery. Some like the Denisons supported the South in the Civil War. But many white people here staunchly opposed slavery and poured a great deal of time, effort and money into welcoming refugees from slavery. Some of the early minstrel shows featured black men and women (born in the American South, not Ethiopia or Nubia as ads proclaimed with more than a little creative license).

Despite their contributions to society, black people were the object of everyday discrimination which sometimes escalated into violence. Black men and women travelling alone were vulnerable to assault. Racist attitudes are epitomized by the jokes and parody in the very popular minstrel shows. White musicians, professional and amateur, put on “black face”, singing songs, playing banjos, dancing and performing slapstick skits.

The Stanley Minstrels! Concert! The Stanley Minstrels in returning their sincere thanks for the very liberal patronage, approbation, and applause, which was bestowed upon them at their two last Concerts, beg leave to announce, that they will give their third concert at the Saint Lawrence Hall, on Monday Evening the 12th March, 1855, On which occasion they will introduce an entire new programme, consisting of New Ethiopian melodies, witty sayings, jokes, black blunders, dancing, &c. To conclude with the Burlesque Ball. (Globe, March 9, 1855)

As black people settled into life in Ontario, they organized their own churches and associations, including organizations to help those escaping from the USA. They also began to gain political power and white politicians solicited their votes. This is a rather back-handed appeal to black voters in Toronto to support George Brown:

“I know you can both reason and judge quite as well as your white neighbours.” “What did Mr. Brown’s paper say and what did Mr. Brown’s friends do, when the Fugitive Slave Bill was passed, making exiles of hundreds of your brethren, and exposing them to the cold charity of the world? He denounced the atrocious wrong, and gave his means to shelter and support its victims.”(Globe, December 12, 1857)

When the war was over, black Americans returned to the US though not to the South. Instead they moved to the large cities of the American north and mid-west: Detroit, Pittsburgh, Chicago, etc. While some stayed most black people in Leslieville joined the exodus. Leslieville and Toronto too became whiter and whiter and racism became more open, acceptable and obvious. Immigration laws and policy tightened to keep people of colour out. Between 1896 and 1907, one and a half million immigrants came to Canada, but less than a thousand were black.

Blacks were not welcome here. Canada’s Immigration Act of 1910 prohibited “any race deemed unsuited to the climate or requirements of Canada”.

On the other hand white immigrants from Britain received a financially incentive called the “British Bonus” for coming to Canada. Immigrants from Britain’s large cities like London, Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds, Birmingham, Glasgow and Belfast, poured into Leslieville from 1890 through to 1930 (with a gap in 1914-1918 when World War I was swallowing a generation). They populated the new streets like Ashdale, Woodfield Road, Craven Road, Hiawatha Avenue, Prust Avenue, Gerrard Street East, etc. Some of these streets became whiter than snow thanks to the use of restrictive covenants in mortgages that kept the property to “Anglo Saxon Protestants”. But, at the same time, a black man was one of Toronto’s most powerful municipal politicians and black people did live here.

THE HUBBARDS

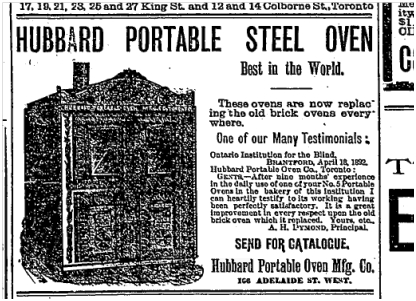

William Peyton Hubbard (1842 – April 13, 1935) was a successful baker who invented a new commercial stove the Hubbard Portable. He trained at the Toronto Normal School (the teachers’ college of the day located on the Ryerson Campus where its façade graces the Quadrangle).

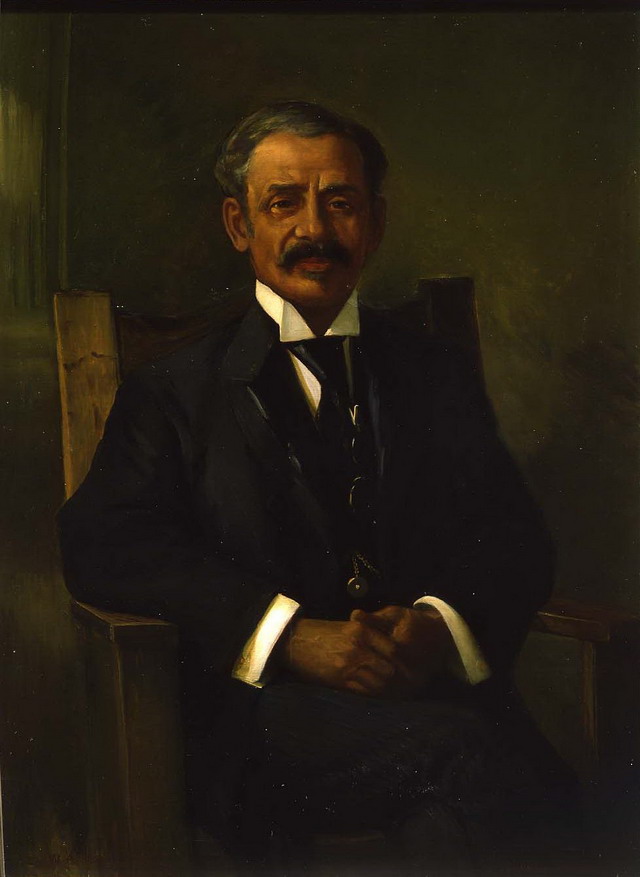

But he was much more than a simple baker. He served as a City of Toronto alderman from 1894 to 1914 for Ward 1, which included both parts of Riverdale: Riverside and Leslieville. He was the first black Canadian to be elected to office in this country. A dynamic speaker, skilled negotiator and popular man, he was Vice chair of the Toronto Board of Control in 1906 and served as acting Mayor when the Mayor was ill or away.

William Peyton Hubbard was a devout Anglican and sometimes the antics at City Hall offended his sense of right and wrong. Leslieville was still a place for city boys to have fun. Young men and men not so young drove their rigs out from downtown. Perhaps inspired by the nearby Woodbine Racetrack, they used the Leslieville’s streets, particularly Eastern Avenue, for racing. In 1896 Aldermen James. B. Boustead, William Peyton Hubbard, John Knox Leslie, J.J. Graham and Mayor Kennedy discussed the relationship of horse racing horses to Methodism at a City Council meeting. The Mayor, in his inaugural address, had suggested that “certain streets be set apart for speeding horses.” Alderman Hubbard was shocked that the Mayor, who was supposed to be a good Methodist, should even think of such a thing. Leslieville Aldermen John Knox Leslie and J.J. Graham moved that Eastern Avenue from the GTR crossing to the Woodbine Racetrack be set apart for speeding. Kennedy supported the motion: The Mayor admitted being fond of a fast horse himself and he believed that there were thousands of people, Methodists among them, who would take a pleasure in witnessing the speeding. (Toronto Star, January 28, 1896)

William Peyton Hubbard (1842-1935), the first African Canadian city councillor in Toronto (first elected in 1894). Painted by W.A. Sherwood (1859-1919)

Alderman Hubbard stood up for the interests of Torontonians preventing the Georgian Pay Ship Canal and Power Aqueduct Company from taking over ownership of the city’s water supply. He chaired the committee that promoting provincial legislation that would allow the city itself to generate and devlop power: the origins of Toronto Hydro. This portrait of William Peyton Hubbard by W.A. Sherwood was commissioned by Ward One voters and hung at City Hall on November 15, 1913. When his wife Julia became seriously ill, he retired from politics but stayed on as the City of Toronto representative to the House of Industry. It was commonly called The Poor House and was on Elm Street (now the old building is incorporated into a YWCA housing project). Julia Luckett died three years later, in 1917 from a stroke.

Courtesy of City of Toronto Art Collection, Museums & Heritage Services

How William Peyton Hubbard got into politics speaks of his character. After 16 years he got out of the baking business and became a taxi cab driver. (However, he loved baking up for the rest of his life.) Hubbard was:

…travelling on Don Mills Road when he noticed the cab in front of him was in danger of plunging into the icy Don River. Hubbard caught up to it and took control of the reins just in the nick of time.

The driver of the cab was drunk, and the grateful passenger who stepped out was George Brown

The driver of the cab was drunk, and the grateful passenger who stepped out was George Brown, the renowned politician, founder and publisher of The Globe. The short wiry youth had just spared the life of a future father of Confederation. Brown had been saved to fulfil his destiny by the man whose own destiny was to be “Toronto’s Grand Old Man,” “Cicero of Council” and the first black man to sit in the mayor’s chair.

John Brix Coleman, “Black Cicero”, Toronto Star, Aug. 27, 1983

It was George Brown who encouraged William Peyton Hubbard to go into politics. William Peyton knew his Ward One voters well, including the brickmakers on Greenwood Avenue, many from that staunch Somerset anti-slavery tradition that gave them minds and hearts that were opened wider than many others of the time.

Isaac and Margaret Ann (Simpson) Price

Isaac was a champion athlete as a young man, representing the Leslieville Rowing Club in numerous races, and winning most. Years later the Toronto Star recalled Isaac Price’s days as an athlete, “Fifty years ago the late Mr. Price was one of the outstanding amateur scullers of Toronto and Ontario.” (Toronto Star, Oct. 13, 1934)

Annie Margaret Simpson Price was the daughter of William Simpson and Catherine Doherty, brickmakers who lived at 55 Curzon Street, in the heart of Leslieville. Two Simpson daughters married two Price brothers Isaac married Margaret Annie and Joseph married Sarah Jane Simpson. Brickmaker families formed a tightly knit web linked by both ties of business and marriage, as well as of friendship. Thomas Sawden, for whom Sawden Avenue, is named, was a close friend despite being a brick manufacturer competing with the Prices.

In 1888 like many other brickmakers, Isaac and Annie Price were still living in their old home on Queen Street East. The brick business had its upside down and, in 1897, during a major economic downturn, Isaac Price’s property taxes were in arrears. With the return of prosperity the Prices grew rich. They built their new home at 216 Greenwood around 1897, at the same time John Price was putting up his home at 100 Greenwood Avenue.

By 1930, Isaac and Annie Price were living at their new home, 294 Strathmore Boulevard, a neat, compact brick bungalow, much smaller than the villa at 216 Greenwood Avenue. Like many seniors today, the Prices had downsized. To see their new home follow this link

At the beginning of January, 1930, they celebrated their golden wedding anniversary. Isaac Price was involved in brickmaking in Toronto for over 50 years. His plant on Greenwood Avenue closed around 1933, during the Great Depression, and Isaac Price retired, only to die just over a year later on October 18, 1934. Margaret Annie Simpson died on February 18, 1949, at Toronto East General Hospital. But the life of 216 Greenwood Avenue went on.

TIEING THE THREADS TOGETHER: ABBOTTS, HUBBARDS AND BINFORDS

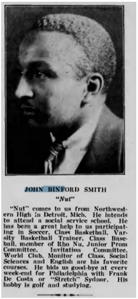

On September 26, 1936, Julia Margaret Hubbard (1910–1998) married John Binford Smith (1909-1974).

Julia Margaret’s father was Frederick Langdon Hubbard (1878-1953), another outstanding member of this interesting family. Hubbard worked for the Toronto Street Railway from 1906 to 1921, and served as the chair of the TTC from 1929 to 1930, vice-chair in 1931 and a commissioner from 1932 to 1939. He was the first African Canadian to serve in these roles on the TTC. Hubbard Avenue is named after him.

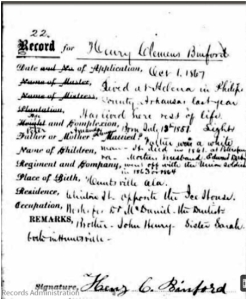

But Julia Margaret Hubbard was not only the granddaughter of William Peyton Hubbard, she was also the grandchild of Anderson Ruffin Abbott. Her wedding was an an evening affair held at the home of friend Cornell F. Milford, 216 Greenwood Avenue. The large drawing room of 216 Greenwood Avenue, with its big French stained glass windows, overlooked the well kept lawn and flower gardens that Annie and Isaac Price had planted and nurtured. The reception was held later in the Hubbard home at 662 Broadview Avenue. A historical plaque marks that Hubbard home. But her new husband has an interesting story as well. Researching the family history of black Canadians can be frustrating for many reasons. Often the sources are missing; sometimes the sources are racist and a researcher has to pick through a lot of garbage to find “a pearl”. But the ultimate wall is the way records were kept under slavery. On the long lists detailing each slaveholder’s human chattels, names rarely appear, just gender and age and sometimes a brief remark. So finding the thread of a family tree before the Civil War is rare. But in the case of John Binford Smith, I was able to trace his family further back.

Henry Claxton Binford, Educator, Newspaperman, and Mason Grand Master From The Afro American, Aug. 20, 1910, grandfather of John Binford Smith

Click to access Yearbook_1931.pdf

Smith’s original name was John Allen Binford Jr., but he changed it when his mother remarried to Alonzo Smith. John Binford Smith was born in the Deep South, at Huntsville, Alabama. His father was John Allen Binford Sr. (1882–1937). John Allen Binford Senior’s father was Henry Claxton (Clemens) Binford (1851–1911) born under slavery to a black mother, Amanda Clemens, and a white father, Peter Binford, whose names we know thanks to Freedman’s Bank Records. Peter Binford was from an illustrious Virginia Tidewater Family related to Robert E. Lee, the famous Confederate General.

The threads from Abraham Lincoln and Robert E. Lee, soldier and slave owner, meet in a house built by proud abolitionists and now the wedding place of descendents of enslaved men and women who had “made it” in “the land over Jordan”, Canada.

Peter Binford, the slave owner of Amanda Clemens, was born on January 31, 1817 in North Carolina. The family moved to the Huntsville area around 1826. This 44-year old lawyer enlisted in the Confederate army on April 26, to work as an assistant to the battlefield surgeons of the 4th Alabama Regiment. Perhaps he chose this non-combatant role because he still had a trace of the Quaker convictions he had been raised with. William Henry Doel and Anderson Ruffin Abbott would have known the work that Peter Binford did. Perhaps he worked himself to death caring for the wounded. In any case, Peter died of pneumonia on June 20, 1861 in Strasburg, Virginia. Dr. L. W. Shepherd said, “I shall always believe he died the victim of too high a sense of duty,” (Huntsville Democrat, May 19, 1961)

See more at

http://huntsvillehistorycollection.org/hh/hhpics/hhr/pdf/Volume_18_2_Jul-91.pdf

Peter Binford can be found in the 1850 U.S. Federal Census – Slave Schedules. As noted, he was originally a Quaker, a member of the same pacifist denomination, the Society of Friends, as others in this story and indeed the Ashbridges family. Some of his Quaker ancestors freed their slaves out of religious conviction as over time slavery became less and less acceptable to this group that believed that all human beings, men and women, all backgrounds and origins were equal under God. In fact, that’s how they got the name “Quaker” as they shook or quaked while they stood before royalty and refused to take their hats off. On March 17, 1792, Quakers Thomas Chappell, John Chappell, Benjamin Chappell, and Agnes Chappell of Prince George County and Aquila Binford of Dinwiddie County:

…being fully persuaded that freedom is the natural right…do unto others…under our care one Negro of the following name Charles Rivers aged 22 yrs, we do therefore emancipate and set free the said Negro.

See more at:

http://www.freeafricanamericans.com/virginiafreeafter1782.htm

The Hubbard-Smith marriage was a bright moment in a dreary decade as the Great Depression brought high unemployment and overcrowded housing to the area around Greenwood and Gerrard. Large houses were chopped up into flats. Families doubled up so that bungalows sometimes had a large number of inhabitants. The housing stock became run down. Although by all reports it was a good neighbourhood to live in and to grow up, it gained a reputation as a slum. By the early 1950s 216 Greenwood Avenue was a rooming house. It was no longer the “Little Britain” it had been called — although the presence of black families like the Lightfoots on Woodfield Road undermine the commonly held belief that the area was all white. The “East End” was now more varied, as Italian and Greek immigrants moved in.

216 Greenwood Avenue appeared again in the news in 1956 when John Michaelides, who lived there, wrote a Letter to the Editor calling for an end to the execution of Greek Cypriots who were trying to overthrow British rule on Cyprus. He wrote:

In case of war, how can he expect anyone to fight for the British again, since they see that they hand those who shed their blood for them in two world wars?

His poignant, but pointed question could apply to people across the crumbling British Empire. (Toronto Star, Sept 29 1956)

In 2003 216 Greenwood Avenue was in the news. David Nickle in The East York Mirror (Aug 1, 2003) described how two group homes one here and one on Simpson Avenue were facing a crisis. The homes were run by L’Arche Daybreak, an innovative program created by Jean Vanier, son of one of a Governor General of Canada, but were threatened with closure. The Ontario Ministry of Community and Social Services took them to task for not being in compliance with City of Toronto Bylaws. They were given a deadline of September 30, 2003, to get things in order. 216 Greenwood Avenue which had been a group home for four adults with disabilities for years. L’Arche provides supportive housing based on a model of community involvement and volunteerism, infused with a gentle spirituality. L’Arche’s problem was that, although they complied with fire code and building code requirements, they needed the City of Toronto to confirm that they were a legal group home. However, they needed a variance of the zoning bylaw because they are within 250 metres of another residential care facilities. The City of Toronto’s Committee of Adjustment refused to consider it because L’Arche had fulfilled the requirement that a sign be posted letting residents of Greenwood and Simpson Avenues know about the hearing. They eventually got their variance.

The thread woven by Ike and Annie Price (Ike to his friends), his brother John and the other Prices and their friends who made 216 Greenwood Avenue ring with music and laughter, still runs through the old house. The shades of all those Red Legs who perished in the West Indies, as well as countless Africans and their descendents also weave strands through the brick and mortar. A strong cord woven by Frederick Douglass would be here too. Somewhere the Black Jacks who ferried so many across the Greats Lakes would maybe be dancing hornpipes. The memory of Abraham Lincoln is netted into the fabric here too. And those of Canadian volunteers like William Henry Doel and James Bird. But stronger still is the cord woven by Wilson Ruffin Abbott and his son, Dr. Anderson Ruffin Abbott and the thousands of men and women who came to freedom in Canada and their descendents some of whom live in this neighbourhood today. Although we may not think about history, we move through it daily, not only in the built environment of houses, factories, bridges, shops, schools and roads, but in our deepest beliefs and aspirations. The house where Julia Margaret Hubbard and John Binford Smith said their wedding vows still stands at 216 Greenwood, a reminder that we are living, woven into history, creating it with our everyday lives in our neighbourhoods and of the courage and tenacity of those who were here before us.

To see more:

http://omeka.tplcs.ca/virtual-exhibits/exhibits/show/freedom-city/stories-of-freedom

Informative and very well researched. Positively written. Perhaps the next step should be a review of the progress made by subsequent blacks and whether they consciously used those written about in the article, as motivating elements in tneir own quest to be “successful”. How would one begin to trackand compare their progress? The 2oth and 21st Centuries would yield loads of information.

Thank you for a thoroughly researched segment of Canadian history of the black presence in Toronto. I was especially intrigued as my sister and I had traveled to Toronto in the mid 1980s to find information on a distant cousin Luella Price. Although our stay was cut short, we did find in the Archives of Canada her will and newspaper articles on her death. I cannot find information on the Eureka Club she was associated with and would love more information if you have any. Also, do you have any more information on William and Mary Cooper, her parents- we cannot establish their link to the Carter/Edwards connection that would explain the cousin relationship with Luella. Thank you for any additional help you can provide.

Regards,

Kathleen Dailey Driver

Gloucester, Virginia

Hi Kathleen, I’ve heard from another member of your extended family asking for information about Luella and Grandison. I’ve posted a call for help out on the Leslieville Historical Society Facebook page and am going to be going through different databases over the next few days. I do have a little “info” on William and Mary Cooper.

This is what I am working with right now for William. (See below.) I am not sure that all of it is accurate. If you could let me know please if any of this corresponds to what you know. The info I have on Luella is more solid with lots of documentation. I will post it on the Leslieville Historical Society Facebook page and the Leslieville Historical Society website later today or tomorrow.

A local reporter with ties to the black community here has offered to help in this search and the word has gone out. A number of historians and genealogists, both professional and self-taught, will likely respond.

Joanne

A WORK IN PROGRESS

When William Edward Cooper was born in September 1838 in Mecklenburg, Virginia, USA, his father, Edwin, was 23 and his mother, Martha, was 19. He married Mary Elizabeth Betty Moss in 1870. They had four children in 18 years. He died in 1900 in Chillicothe, Ohio, USA, at the age of 62.

William Edward Cooper was born in September 1838 in Mecklenburg, Virginia, USA, to Martha , age 19, and Edwin Cooper, age 23.

black

His sister Martha was born in 1842 in Virginia, USA, when William Edward was 4 years old.

His sister Nancy was born in 1844 in Virginia, USA, when William Edward was 6 years old.

His brother James was born in 1845 in Virginia, USA, when William Edward was 7 years old.

His sister Elizabeth was born in 1846 in Virginia, USA, when William Edward was 8 years old.

His sister Amanda was born in 1847 in Virginia, USA, when William Edward was 9 years old.

William Edward Cooper lived in Mecklenburg, Virginia, USA, in 1850.

Regiment 98, Mecklenburg, Virginia, USA

His daughter Luella was born on June 30, 1858, according to her death certificate.

Luella Cooper

1858 abt–1935

30 June 1858 • Caroline County, Virginia, USA

William Edward Cooper lived in Mecklenburg, Virginia, USA, in 1860. (Slave)1860 • Regiment 98, Mecklenburg, Virginia, USA

His son “Robert” Edward Lee was born on October 10, 1867, in Mecklenburg, Virginia, USA.

“Robert” Edward Lee Cooper

1867–1951

10 October 1867 • Mecklenburg County, Virginia, USA

His daughter Ann E was born in 1869 in Virginia, USA.

Ann E Cooper

William Edward Cooper lived in Boydton, Virginia, USA, in 1870.

Post Office: Boydton

William Edward Cooper married Mary Elizabeth Betty Moss in 1870 when he was 32 years old. (They probably had a church ceremony long before this but before Emancipation it was not legal to marry slaves.)

Mary Elizabeth Betty Moss

1850–

1870 • Washington, D.C.

His daughter Esta “Estie” Mae was born in 1878 in Ohio, USA.

Esta “Estie” Mae Cooper

1878–1953

William Edward Cooper lived in Washington, District of Columbia, USA, in 1880.

Marital Status: Married; Relation to Head of House: Self. Engineer.

William Edward Cooper died in 1900 in Chillicothe, Ohio, USA, when he was 62 years old.

Thank you so much for responding! I will wait and contact the other family member(s) who are on Facebook for future posts….again, your research has been most helpful.

Kathleen

This insight to the history of the area I grew up in (Hiltz) avenue is very interesting