Albert Henry Wagstaff came into this world on September 10, 1870, at the family home just west of Leslie Grove on Kingston Road in Leslieville, in the County of York. A handsome charmer, excellent public speaker, astute businessman and notorious womanizer, he also had a wicked sense of humor outlived him. Thinking on your feet and being good with your fists was a Wagstaff feature. They were tough men, not generally charmers, though Albert was an exception and he had a sense of humor was not always appreciated, as you shall see.

On the promise that the Government would give him a land grant, 40 year old Robert Wagstaff, still suffering injuries sustained in a number of battles, immigrated to Canada in May, 1834. One source says that he came to Toronto as a soldier. In any case, he was in Toronto by December 1834 and fought as a solider for the Crown in the Upper Canadian Rebellion of 1847. Elizabeth and his children joined him sometime around 1836.

Brickmaking was a family affair in the early days. Robert would have been the brickmaker while his gang of hands would have included the children. Robert, as moulder, would have stood at the moulding table. His children were the ones who carried the clay to the moulding area, sometimes on their heads. Robert made the bricks entirely by hand using wooden moulds. Elizabeth would have been the clot moulder. Her job was to cut the lumps into a brick-sized piece or clot. She then passed the clots to Robert. Robert would have stood, despite his wounds, at the moulding table from 12 to 15 hours a day, six days a week. He could make up to 25,000 bricks a year – by hand. The children often moved the finished bricks across the brickyard in a daisy chain, all the children spread in a line spanning the yard. One child would toss a brick to the next until all the bricks were moved, often tons. The children sang as the tossed the bricks.

Robert Wagstaff came from generations of brickmakers as Gamlingay, his birth place in Cambridgeshire, England, had an old brick making industry. He started working in a brick yard when he was a child. It dirty, wet, cold and back-breaking work. The family breathed in brick dust and the smoke from the kiln all day and usually all night as they lived near where they worked. Respiratory disease killed many men, woman and children in brick making families, but accidents also took a high toll. (For a description of early brick making see Sandra Garside-Neville, “Brickmaking in 19th century York: a preliminary survey” at http://www.tegula.freeserve.co.uk/BRICMAK.HTM)

Elizabeth Quince (1806–1873) gave birth to ten children. Three died in infancy. When Robert died she was left alone with seven children. (Robert had two children with Ann Whiston. His wife and two children died before 1823. In 1824 he married Elizabeth Quince.)

David Wagstaff was born on March 20, 1841, in Toronto, Ontario. His father, Robert, a brickmaker, was 48 and his mother, Elizabeth, was 36. His father was dying when David was born. An American bullet smashed into Robert’s neck at the Battle of New Orleans. (Regimental Registers of Pensioners Rifle Brigade and Miscellaneous Corps, 1806-1838) He served with The Rifle Brigade.

Robert Wagstaff passed away on August 12, 1843 when David was a toddler. (Regimental Registers of Pensioners Rifle Brigade and Miscellaneous Corps, 1806-1838) When he died, without the promised land grant, Elizabeth was left destitute. Two of her children were under three years old: William was only three, David was just two.The oldest Elizabeth Anne was 17. Mary was 15. Louisa was 12. The girls would likely have gone into service, working as maids in middle class households. Even Caroline at nine may have worked as a servant. One of my ancestors was working as “tweenie” or between stairs maid at that age. (A “tweenies” job was to carry things up and down stairs all day for 14 or hours a day, seven days a week.) Robert Wagstaff was 14 and had likely been working with his father in the brickyard since he was five or six years old, as the girls probably were too as well as Elizabeth Quince.

In December 1843, Elizabeth petitioned for a land grant. It was rejected. Seven months later, on July 29, 1844 she married another brickmaker, Robert Reid. The family later moved to Leslieville. Reid Street, now Rhodes Avenue, was named for this family. Her marriage to Robert Reid may have been arranged by Robert Wagstaff himself before he died. British soldiers often made such arrangements with bachelor friends so that their families would be looked after when they were killed or died of sickness or wounds. Sometimes these were last-minute arrangements before battle, but often they were long-standing pacts between soldiers with their wives’ knowledge and consent. In this case Robert Reid was a widower with five young children of his own. His wife, Harriet Sanders, had died in 1842. I think it very likely that Robert Reid was a veteran of the Napoleonic Wars as well, and perhaps of the Battle of New Orleans. A Robert Reid had fought in the War of 1812 in the US. He was with the 48th Regiment of Foot. A Robert Reid also served in the militia in Toronto during the Upper Canada Rebellion.

The Wagstaff boys had worked from a very early age in the brickyards. By 1851 David was living with his mother and stepfather in Leslieville and probably working in Robert Reid’s brickyard with his brothers. David and his brothers were tough men who occasionally got into trouble with the law for assaulting police and roughing up other people, as well as abusing their teams of horses. One brother, Robert, was part of the notorious Brook’s Bush Gang of thugs and murders that haunted Withrow Park’s area.

David Wagstaff married Matilda Sear (1848–1917) in 1864. She was also from a brickmaking family. They had a large family, but as was common at that time lost some in infancy. Life was tough. Infant mortality was high. In addition to Albert, their children included: Philip John Wagstaff (1867-1868), Elizabeth Ann Wagstaff (1868-1869), Dora Matilda Wagstaff (1872-after 1968), Charles Wagstaff (1874-1934), Ada Florence Wagstaff (1878-1951), and Evaline May Wagstaff (1884-1951). For more about the Wagstaff genealogy go to Jim Harris’s well researched and interesting website: http://harris-history.com/tree/1432.html

In 1883 David Wagstaff built a large home out of his own bricks at 1140 Queen Street East, next to his brickyard. He had a long career as a brick manufacturer and was highly successful.

Matilda Sear died in 1917. David Wagstaff married Annie Louisa Cruttenden on September 4, 1920. He died on September 13, 1928, in his new home at 650 Broadview Avenue. He was 86.

Albert went to Leslie Street Public School where he won a prize for the maps he drew and he became a member of the Leslie School Old Boys later. Albert began working as a boy in the brickyards, learning the trade at his father’s side. Albert married Frances Gertrude Buckland on November 18, 1892 in Toronto, Ontario. They only had ten years together and it is apparent that he loved her deeply. She died in February 3, 1902, aged 33 years from chronic septic meningitis related to nephritis or kidney disease. (Today she would like live with dialysis and a kidney transplant.) They had three children: David Henry, Vera Winifred, and Frances Irene who died at only nine months of age and on March 18, 1902. Within only about six weeks Albert lost both his wife and his baby daughter. He must have wondered if his little child would have survived with a mother.

On June 4, 1902, in Muskoka, David Wagstaff married Margaret Diemal, his housekeeper and nanny to his children, only four months after Frances Gertrude Buckland died. Perhaps he married her so quickly to have a mother for his three young children, but this certainly shocked Leslieville. Marrying a servant just wasn’t done. Class distinctions mattered.

That year David Wagstaff sold a 30 by 200 foot lot on the west side of Jones Avenue to Albert Henry Wagstaff, assessed at $800 an acre, for one dollar, for his new home at 40 Jones Avenue. That lot was 400 feet north of Queen. He sold the lot next door to his son Charles, also for a dollar. (Toronto Star, January 11, 1902)

Other brickmakers considered Bert Wagstaff a highly skilled craftsman as well as a shrewd businessman. With the introduction of new technology, better rail and road transportation, and competition, the brick making industry began to reorganize. It had been dominated by small family owned and run brickyards throughout the nineteenth century. Now the industry began to consolidate into larger and larger brickyards, hiring more workers. David Wagstaff owned several brickyards, including one on Greenwood Avenue, but in 1905 Albert H Wagstaff went into business for himself and built a large new modern plant at 348 Greenwood Avenue, next to the Grand Trunk Railway line. Here he had originally had only ten acres of brick clay about 75 feet deep. His operations soon moved north the railway lines. His brickworks specialized in purple and black brick. (Toronto Star, October 4, 1915). The plant and brickyard (long closed) remain on Wagstaff Road. His brickyard had “the latest and best machinery” including artificial dryers and down draft kilns. This allowed Wagstaff to make bricks all year round. He employed about 30 men. It was said that “few men being able to so thoroughly understand the mechanical part of the work, and at the same time successfully conduct the financial part of the business”. (Commemorative Biographical Record of The County Of York. Toronto: J H. Beers and Co., 1907)

Albert Wagstaff was not an armchair boss or a white-collar man. He had worked in his father’s brickyard from a very young age and continued to do hard physical labour through most of his life. In June 1906 he was working in his brickyard on Greenwood Avenue north of the railway line when he lost his balance and fell. The heavy post he was carrying toppled on top him causing internal injuries and damaging his shoulder. He was living at 40 Jones Avenue at the time, not far from his childhood home where Bertmount Avenue (named for him) is today. (Toronto Star, June 17, 1905)

Technology probably made the work more, not less, dangerous. Many men died in the brickyards of Leslieville. For example, in 1905, a ton of clay fell on William Broomsgrove, in Albert Wagstaff’s shale pit on Greenwood Avenue, north of the railway tracks, crushing him. (Globe, October 30, 1905) In 1908, another man died the same way in another Leslieville brickyard. Emerson Benns, was working in the Bell Brothers brickyard, at 301 Greenwood Avenue, digging clay from the side of the pit when a piece of hard clay fell on him from about 12 feet above, killing him instantly. Such deaths were common and the coroner Pickering decided that no inquest was needed. (Toronto Star, May 23, 1908) In 1907, a hurtling dinky loaded with clay smashed into David Chapman, in a brickyard on Dawes Road, east of Leslieville. It knocked him into a puddling machine where “a dozen rapidly rotating knives” mangled his body. In this case, David Chapman owned the brickyard. (Toronto Star, August 19, 1905) The year before another brickyard owner was knocked into a clay-mixing machine. (Toronto Star, July 7, 1906)

In 1906 Albert Wagstaff took over as head of the brick business founded by his father, David, in the 1860s. (Toronto Star, April 20, 1931) The family brick plant gradually became a thing of the past so that by the 1930s large plants using modern methods and machinery shipped bricks across the province from production centres. Brickmakers had to use modern dryers, steel trucks, automatic cutting tables, disintegrators, brick machines, mould sanders, etc. to compete. The kilns were fueled with wood or, sometimes, coal. Albert Wagstaff chose coal. The others used wood. (M. B. Baker, “Clay and the Clay Industry of Ontario”, Ontario Bureau of Mines, no. 5, 1906, pp. 109-110)

Four more yards lay north of the rail line on Greenwood Avenue. These yards were:

- John Logan,

- Albert Wagstaff,

- Isaac Price,

- and J. E. Webb.

These brickyards extracted shale from the deep deposits north of the Grand Trunk Railway by using a steam shovel set on a railroad car on a portable narrow-gauge rail line. The shovel and the locomotive were called “a Dinky”; the cars were “Dinky cars”. 20-ton saddle engines were often used. They dug the typical Leslieville clay but also shale. The brickyards sat at the top of the banks of a ravine over 100 feet deep. The shale was blasted out with dynamite, dumped into dinky cars and steam engines hauled the raw material up the steep on cables to the nearby brick plants. A.H. Wagstaff produced about three million bricks a year as well. In 1912 at the A.H. Wagstaff yard on Greenwood Avenue, a Martin brick machine could turn out 85,000 brick a day. (Toronto Star December 11, 1912) All four brickyards turned out “very excellent hard red brick”. (Baker, 110-111)

Tragedy struck the Wagstaffs in April, 1908, when their daughter Lila Alberta died from pneumonia at just under a year old. They were living at 40 Jones Avenue at the time in the house Albert built on land his father sold him for a dollar. (Toronto Star, April 29, 1908)

In 1912 five and half acres of land, the original David Wagstaff brickyard, on Queen Street, between Coady and Brooklyn Avenues, was sold to Charles Miller for $45,000 or about $8,000 an acre. (Globe, May 3, 1912) The brickyard was subdivided houses with a row of new stores on Queen Street, including what is now the Tango Palace. David Wagstaff lived at 1140 Queen Street East and then in 1913 he moved to a newer, much larger house at 650 Broadview Avenue (built 1912). 650 Broadview in Toronto was adopted by the Toronto City Council in 2006 and designated a historical home due to its unique architecture.

Meanwhile Bertmount Avenue was laid out north and south through the brickyard and named after Albert “Bert” Wagstaff. The 1912 Might’s City Directory shows two houses under construction on the west side of Bertmount and none on the east side. By 1914 Bertmount was almost completely built up with new houses.

LABORER INJURED.

While working in Wagstaff’s brick yards on Greenwood Avenue yesterday, Metro Rastich, a foreigner, living at 15 Percy street, had his left leg seriously crushed when it was caught in a clay mixer. He was taken to the General Hospital by the Shields emergency ambulance. It was stated that the leg would have to be amputated above the ankle.

(Globe, June 2, 1914)

Metro Rastich sued Wagstaff for $5,000 in damages for the loss of his leg, but settled out of court for $1,000. (Toronto Star, May 3, 1915)

He ran for election to City Council as an Alderman for Ward One. His literature promoted him as “A successful business man who will make a successful alderman.” (Toronto Star, December 19, 1914)

On March 12, 1915 swept through Albert Wagstaff’s brickyard at Greenwood Avenue, completely destroying the plant. None of the buildings survived the blaze and Wagstaff’s machinery was destroyed as well. About 40 men were laid as a result. The loss was worth $15,000 in the currency of the day. Fires were a common occurrence in brickyards due to the large piles of coal or wood used to fire the kilns, along with sparks from the kiln chimneys. Insurance was almost impossible to get and this brickyard was not insured.

“It was stated at Pape avenue police station yesterday that the police of that division have considerable trouble in keeping the brick yards on Greenwood avenue free from tramps and others who have no homes. The brick yards are accessible at all times to any of these wayfarers.”

Number 26 Fire Station was on the west side of Greenwood Avenue at northeast corner of the shale pit, conveniently placed near the brickyards with their frequent fires. Number 8 Police Station was on the west side of Pape north of Queen. It is now an ambulance station.

Albert Wagstaff wanted to get a building permit and rebuild right away, but he expected obstacles:

“There is so much red tape at the City Hall that I doubt whether we will be able to resume operations before the fall. It takes a great deal of time to obtain a permit for the erection of a factory.”

(Globe, March 15, 1915)

However Wagstaff was back in operation within days as the newspapers report that one of his employees, A. Jones, 27 Condor Avenue was killed on April 4 in his brickyard. (Globe, April 5, 1915)

I have included the official report on the accident verbatim except for putting in paragraph breaks to make it more accessible to the modern reader.

H. Wagstaff’s Brick Works George Jones, native of Sopham, England, aged 43, married, with wife and three children, was instantly killed by fall of clay from the working face at 10.30 a.m., April 4th, 1913.

Jones, in partnership with Chas. Treleving, held a contract from A. H. Wagstaff to supply his brick machines with clay at a price per 1,000 brick manufactured. They employed Jones’ son, George Jones, Jr., as helper, and these three men performed all the work in the clay pit. This contract or piece-work system appears to be almost universal in the brick business, as is also the method of working the pits, viz., boring stope and breast holes with auger and caving the whole face, after the top soil has been stripped.

On the morning of the 4th inst, Jones and Treleving shot a round of six holes along the face, which at the point they were working is about 40 feet high and 50 feet across. The clay is of a tough rubbery nature, and does not appear to shatter like a rock structure, but breaks in thin slices and large square blocks. As a result, there is generally, after each round of shots is fired, considerable overhanging left, which is scaled down at once, or if left for some hours will generally fall of its own weight.

On the morning of the accident the shots were fired at 8 a.m., and the face left for two hours to see if it would clean up. A large piece of overhanging was left in the middle of the face, and when it did not come down, Jones and Treleving decided to bore two holes to the bottom and right of it, in order to dislodge it completely. Jones was working nearest the dangerous portion, and they had just commenced their holes when the piece fell, and Jones was caught. Treleving got clear. George Jones, Jr., had been stationed farther back from the face to watch the overhanging and give warning if it showed signs of coming loose. He gave the signal, but Jones, Sr., apparently tripped while running over the broken clay and was jammed by a large piece, and the lower part of his body buried.

Death was instantaneous, for the post mortem showed that one bronchial tube was completely severed and several ribs broken, causing immediate suffocation.

Jones had been in the employ of Wagstaff since February 1st, 1913, but previous to this had worked several years in the clay pits of adjoining brick yards, and was considered a careful, competent man by his employers. His partner, Treleving, is also an experienced clay man.

The accident was caused by the carelessness and poor judgment shown by the partners in working so dangerously near the overhanging portion. That they were aware of the danger and were taking chances was clearly shown by the fact that the third man in the pit was taken from his regular work of loading the cars, and placed as a signal man to warn them of danger.

The body was examined at the pit by Dr. Parker, of Greenwood Avenue, within a few minutes after the accident. Dr. Watson, of Euclid Avenue, performed the post mortem examination, and the inquest was held at the Lombard Street morgue on Thursday, April 10th, at 8 p.m., by Dr. Wilmot Graham. The coroner’s jury returned the following verdict: “That Mr. George Jones came to his death on April 4th, 1913, in the brick yards of Mr. Albert Wagstaff while employed in his vocation as a brick yard man and excavating clay from the bank, and that death was purely accidental.”

(E. T. Corkill, Chief Inspector of Mines. Report on the Mining Accidents in Ontario for April, May and June, 1913. Bulletin No. 16. Department of Lands, Forest and Mines, Ontario, pp. 17-18)

Death on the job was accepted as one of the costs of working for a living at that time. Health and safety did not have the priority it has today. The high accident rate was not usually held against brickmakers, like Albert Wagstaff who was active in the Ward One Conservative Association and hoped for career in politics.

Albert Wagstaff had the backing of the County Orange Lodge in his run for City Council. He was not an Orangeman himself, but his father, David, was active in the Orange Lodge. The Orange Order put forth its own slate of candidates for municipal office, including Thomas (Tommy) Church for Mayor and for Alderman in Ward One (the Riverdale area: Robbins, Hiltz and Wagstaff. Orangemen were not only encouraged to vote them but to work actively on their behalf. (Toronto Star, Dec. 31, 1915)

Toronto Mayor

January 1924 – January 1925

William Wesley Hiltz, a man who stood for everything Albert didn’t, defeated Bert Wagstaff by 180 votes. “Bill” Hiltz was a contractor as Bert Wagstaff was (one of his many roles), but that and an interest in politics was all they hand in common. Bill Hiltz was a devote Christian, born again, strongly for prohibition of all alcohol and against vice of all kinds. The winning candidates for Alderman were William D. Robbins, Albert Walton and Bill Hiltz.

During the First World War, there was a labour shortage due to the number men who enlisted and went overseas. Most brick manufacturers still used teams of horses and wagons, driven by “teamsters”. By the middle of the War, teamsters were hard to find. Wagstaff had to close down his brickworks from time to time due to the shortage of teamsters. “He stated that he was offering the highest wages ever paid teamsters”. (Toronto Star, June 7, 1916)

He was a member of the Woodgreen United Church and apparently attended church regularly. Yet obviously he was not a strict Methodist in any sense. Albert H. Wagstaff’s reputation as a drinker was well established, but it didn’t prevent him from running for Alderman or from winning in the past. Prohibition didn’t stop him from drinking either. He had a sharp wit and was an excellent public speaker. At one election meeting in Ward One (this area) in December 1916 a heckler shouted, “Wouldn’t you like to have a drink?”

Wagstaff shot back, “Just had one, and if any of you boys want one I know where it’s kept.”

He promoted himself as someone who had lived all his life in Ward One. His previous experience as an Alderman fitted him for the post. He was an employer “interested in not only one section or subdivision, but in the whole east end.” Since he paid heavy taxes himself, he understood the need to reduce taxes and have a fairer assessment system. He wanted to bring more industry to Toronto and keep factories from moving out of the city. Finally, in a slogan seems somewhat odd to us today, but was understood at the time, he promised to, “Live and Let Live”. He said that he was “a consistent believer” in this at a time when the calls for complete prohibition of alcohol were mounting. (Toronto Star, Dec. 29, 1916) In 1916, the Ontario Temperance Act was passed in the Legislature virtually outlawing the sale and consumption of alcoholic beverages.

He lived fast and drove fast, getting speeding ticket after speeding ticket. He simply responded that “he would tack on another dollar or so on the prices of the bricks which he manufactures.” That way his constituents would pay his fines for him. Apparently everyone laughed. (Toronto Star, Dec. 30, 1916)

Aldermen Robbins and Hiltz won re-election, but Albert H. Wagstaff lost the 1917 municipal elections. Bill Hiltz again defeated Bert Wagstaff for Alderman by 1,900 votes. Over the year 1916 Wagstaff had hardly been active in City Council, often not showing up for Council meetings. As well, his position against public ownership of utilities alienated many of the working class voters in Ward One. (Globe, January 1, 1917)

By 1917 brickmakers like Albert Wagstaff could not get enough coal to operate. They now burned coal instead of wood in their modern kilns. No longer an Alderman, but with connections, Wagstaff used every contact he had to try to get fuel for his brickyard. Orders for bricks were coming in and he made an arrangement with coal mine owners in the US to get a delivery. The Globe reported, “In normal times Toronto brickyards east of the Don turn out 60,000,000 bricks early and employ 400 men and 90 teams.” (Globe, March 24, 1917)

When the economy was in a downturn and buildings weren’t being built, bricks didn’t sell. At other times, Wagstaff’s plant produced more bricks than the market could absorb. When he had overstocks of bricks he built low-rise apartment buildings and houses, including some near his Wagstaff Drive brick plant. In 1918 Wagstaff received a building permit to put an apartment house and garage at 320 Greenwood Avenue. They were worth about $10,000 in the money of the day. (Globe, July 16, 1918) He named the apartment building the Vera Apartments after his daughter Vera. This building is made with some of A. H. Wagstaff’s purple and black bricks and is a showcase for his specialized products. The apartment building turns away from the Greenwood Avenue. Its monumental front entrance faces the brick plant, not the major street nearby. The original Wagstaff home is buried behind factory additions, but can still be seen from the front steps of the Vera Apartments and from the east side of Greenwood Avenue.

Around this time he also built the Avalon Apartments at Gerrard and Woodfield Road, and the Louise and Alberta Apartments at the corner of Doel and Curzon. Some of the units had three rooms and a bath with oak floors and trims, as well as private garages at the rear. (Globe, Nov. 14, 1923) Doel Avenue is now part of Dundas Street East. The Louise is now listed at 1480 Dundas Street East and the Alberta is 1492 Dundas Street East. The garages still exist, but appear to have been converted into apartments. All Wagstaff’s buildings were sturdy and constructed with Wagstaff’s own bricks, built like the proverbial brick —-house.

He gained considerable rental income from the apartments and the sale of houses, but there were other advantages. Albert Wagstaff installed lady friends Margaret Paterson (in the Avalon) and Mrs. McCague (in the Louise Apartments) in apartments in his buildings.

Albert H. Wagstaff ran for City Council in 1919, but lost to William Wesley Hiltz again. He defeated Bert by 1,178 votes. The top three candidates, Frank Marsden Johnson, Richard Honeyford and Bill Hiltz took their seats in January, 1920, as Ward One’s aldermen.

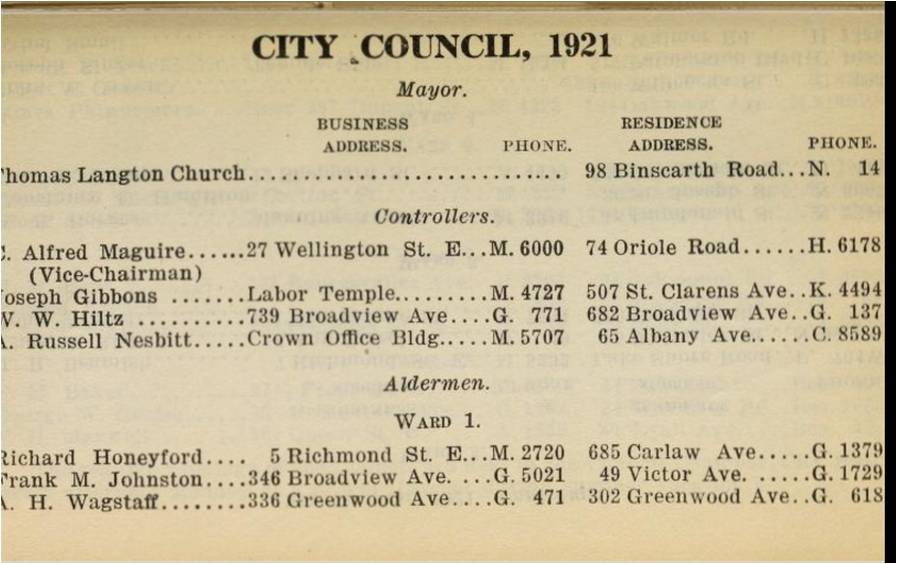

In the fall of 1920 Bill Hiltz didn’t run for Alderman in Ward One. Instead he ran for Controller and won. Without competition from his arch demise, Bert Wagstaff came in third and became a City Alderman again, this time for the last time. He won by 308 votes, taking his seat in January 1921. Despite his efforts Albert Henry Wagstaff only represented Ward One as Alderman for two years, in 1916 and 1921. I find no record of him running again. (Municipal Handbook City of Toronto. Compiled by the City Clerk. Toronto: Carswell Co., Limited, 1921.)

Bert Wagstaff demonstrated his sense of humour again when the 1921 Census taker came around to one of his properties in Scarborough. He had already been enumerated on Greenwood Avenue in York East as a brick manufacturer, but he had himself and Margaret enumerated again. He gave his occupation as “farmer” and with a specialty. He was a “brick farmer”. Later the Scarborough Census officials crossed out both Albert Wagstaff and Mrs. Wagstaff’s names.

By the 1920s, a combination of increased demand for bricks and mechanization of the brickmaking process depleted the East End brickfields. The success of the brickmaking industry spelled its own dooms as the spreading subdivisions of red brick houses buried the area’s remaining clay beds. Some of the contractors building those homes found themselves in a cash bind. Their cash flow did not allow them to purchase the bricks they needed to finish the houses they had started. Brick manufacturers did not offer credit. However, Albert Wagstaff let them place orders on the basis of a simple handshake. By such generosity he won the loyalty of his customers. His workers also, apparently, felt the same by and large.

However, suburbia did not want the brickmakers. From the building boom around 1912 and onwards, Leslieville residents began to complain of being trapped between the smells from the Morley Road sewer plant, the smoke from the garbage incinerator, the reek of filthy creeks and ponds (including Small’s Pond) and the constant smog and noise of the brickyards. These made some parts of the East End less than desirable for housing and brought down property values, allowing home-owners to appeal their tax assessment.

An astute businessman, Bert Wagstaff diversified his holdings even more. In 1922 he built a new factory on Greenwood Avenue next to his old brick plant to manufacture trucks, the motorized kind. A taxi depot occupies this site today. (Canadian Wood Products Industries, 1922)

These brickmakers had team tracks (their own CNR sidings) in 1926: J. Lucas & Co. 359 Greenwood Ave.; John Price Ltd., 395 Greenwood Ave.; Toronto Brick Co Ltd., Greenwood Ave.; and Albert H. Wagstaff, 348 Greenwood Ave. (R. L. Kennedy, “History of Private Sidings”) at http://www.trainweb.org/oldtimetrains/industrial/history/train_sidings.html

According to the 1921 Might’s Directory, Joseph Russell still remained in business at 40 Blake. He had sold his Greenwood Avenue brickyards for housing: Alton, Sawden, Stanton, etc. Along Greenwood Avenue there were: A. H. Wagstaff, 302 Greenwood Ave. and 336 Greenwood Ave.; Price & Smith, 386 – 436 Greenwood Ave.; John Price, Ltd., 395 Greenwood Ave.; Standard Brick Co., 460 Greenwood Ave.; and John Logan, 471 Greenwood Ave. (Might’s Directory 1921, 282 – 283) This was far fewer than ever before.

In 1926, according to the Might’s City Directory there were only four brickyards left on Greenwood: J. Lucas and Co. at 359 Greenwood Avenue; John Price Ltd. at 395 Greenwood Avenue; Toronto Brick Co Ltd.; and Albert H. Wagstaff at 348 Greenwood Avenue. Success spelled its own doom as the clay began to be used up. There were only 14 plants in all of York County in 1930 compared to 30 in 1906. (Robert J. Montgomery, “The Ceramic Industry of Ontario” in Thirty-Ninth Annual Report of the Ontario Department of Mines. Vol. XXIV, Part IV, 1930, 9)

“On both sides of Greenwood were brickyards, and we used to play there weekends. The west one is now T.T.C. yards, and the eastern section is now a subdivision of houses. I have sometimes wondered whether the eastern one (which is built on landfill), since it was a deep hole, extending nearly over to the fence at Monarch Park, would find any of the houses sinking. They had a narrow rail line going down into the hole, where they let down a small dump car [dinky] to haul up the clay for their bricks.”

(Ken Smith. The East End: Personal Recollections of Toronto, East of the Don River from 1915. Toronto: The East End Seniors’ Educational Volunteer Organization, n.d. Brochure, 8.)

Albert Wagstaff owned a farm in Scarborough where he raised prize-winning shorthorn cattle. (Globe, June 16, 1927) His farm was near Wexford. His barn burned in 1925 and he rebuilt it shortly afterwards. It was reported in the newspapers as it was one of the few barn fires that fall and also, probably, because it was the notorious Bert Wagstaff’s barn. (Globe, Oct. 12, 1925).

On May 14, 1928, some workmen found an overturned car in flames in a ditch near Birch Cliff in Scarborough, but the driver and occupants had left the scene. There was blood and scattered clothing around the wreck. The workmen had seen a man with two women pass by them in the car. The workmen saw the car disappear out of sight, but then heard two loud explosions. The car burst into flames, hit a concrete culvert and rolled over in the ditch. Some unidentified person called the police. Although someone was probably seriously hurt, none of the hospitals nearby had any patients that fit the picture and none of the nearby physicians had treated any injured man or women that night.

Albert Wagstaff owned the car, according to the police. (Globe, May 15, 1928)

The Toronto Star in a brief article “Former Alderman Turns Up Safely”, solved the mystery of how Albert Wagstaff got medical help after leaving the scene of his accident. He went to his own family physician Dr. H. R. Holme on Gerrard St. E. and was taken care of privately. (Toronto Star, May 15, 1928)

On May 16, The Globe reported that they had interviewed Albert Wagstaff’s son. His son confirmed that it was Albert Wagstaff driving the car that wrecked on Kennedy road near the Pine Hill Cemetery. Bert Wagstaff had sustained serious head and back injuries. The two passengers were also injured. However, his son claimed that they were men, farmer laborers, that Wagstaff was bringing back to Toronto from his farm in Scarborough. He also claimed that an automobile that just happened to be passing picked up the injured Wagstaff and his passengers. He gave no reason why the crash was not reported to the police even though the newspapers and radio were broadcasting that the police were seeking information. The accident was supposedly caused by a tire blowing out, not alcohol. The police were still investigating and refused to release Wagstaff’s badly damaged car. (Globe, May 16, 1928)

Wagstaff liked fast cars, fast boats, work and women. Not long before his death he advertised in The Globe:

WANTED – MOTOR BOAT, ABOUT A 35-footer, for Lake Simcoe; must be in first-class condition; speed not less than 25 miles per hour. Apply A. H. Wagstaff, 348 Greenwood Avenue, Toronto.

(Globe, Feb. 11, 1930)

As time passed the control of the brick industry became more and more concentrated. There were only 14 plants in York County in 1930 compared to 30 in 1906. (Montgomery, 4.) Albert was involved in the brickyard up until his last illness.

Albert H. Wagstaff died on April 19, 1931 in Toronto Western Hospital after an operation to help his chronic bronchitis. Wagstaff suffered from ascites, an abnormal accumulation of fluid around his lungs due to years of heavy drinking. Cirrhosis of the liver was a contributing factor. At the time of his death he was separated from his second wife, Margaret Diemal. She was living at the big new family home at 320 Greenwood Avenue near the brickyards. He was living in one of the twin apartments he owned on Doel Avenue. The Toronto newspapers published his obituary (see The Globe, April 21, 1931), but a lot more printer’s ink would soon be spilled over Bert Wagstaff.

At the time of his death he owned a lot of property in the East End. He was a Mason, a member of the King Solomon Chapter of Royal Arch Masons, the Knight Templar and Ramses Temple of Mystic Shriners. ()

Albert Henry Wagstaff’s sense of humour went beyond his grave. A heavy drinker and known “womanizer”, he left a contentious estate. His assets totaled almost $260,000, a huge amount during the Great Depression of the 1930s. He owned the Louise and had equity in the Alberta Apartments and equity as well in the Avalon Apartments on Woodfield Road. He owned land, houses and warehouses at 302 Greenwood Ave, as well as equity in the land and brickworks north of the railway line. He also had mortgages, stocks and very little cash.

He left the Wagstaff brick works, including all the land and machinery, to Albert Harper, a drinking buddy. Normally businesses were passed down to the sons and that is certainly what one his sons expected. He left his wife Margaret Diemal the property at 302 Greenwood Avenue. The rest of his property was divided among his children: David Henry, Vera, Lulu and James – and two female friends Margaret Paterson, no relation, and Mrs. McCague, no relation, both local women much younger than Albert. The residue of his estate was left to the Old Boys’ Association of the Leslie Street School. (Toronto Star, May 15, 1931)

His body had barely settled in his grave when his family began contesting his highly controversial will. Many things about the will ticked his wife and son off, but one of them was the fact that Wagstaff left his ownership of part of that huge brick pit and the brick plant on Wagstaff Drive to his drinking buddy, Albert Harper, not the family.

PROBATE IS GRANTED FOR WAGSTAFF WILL

Estate of $259,084 To Be Divided as Sustained by Court

Probate of the will of Albert Henry Wagstaff, brick manufacturer, who died April 19, 1931, leaving an estate valued at $259.084.47, has been granted on the application of Albert Harper. The will was the subject of a supreme court action, being contested by the widow, Margaret Wagstaff, on the ground that it had been obtained by fraud and undue influence, but after a lengthy hearing Mr. Justice Kelly found that it had been well proved.

The estate is comprised mostly of apartment and dwelling houses, and Margaret Wagstaff, widow, is left five houses in rear of Wagstaff Dr. and 302 Greenwood Ave. Vera Sparks, daughter, receives the Vera Apartment, Greenwood Ave., property on Gerrard and Curzon Sts., and Elm St., Oshawa; James Wagstaff, son, a farm containing 100 acres on Kennedy Rd; David Wagstaff, son, Alberta Apartments, Doel Ave.; Lulu Wagstaff, daughter, eight houses on Ivy Ave. and vacant lot; Margaret Paterson, no relation, Avalon Apartments, Gerrard St.; Mrs. H. D. McGue [McCague], no relation the Louise Apartments, Doel Ave.; Albert Harper, no relation, all land, buildings and equipment in connection with brick works on Greenwood Ave.; Richard H. Greer, K. C., large diamond ring; Old Boys’ Association, Leslie St. school, residue.

Assets are real estate, $244,094.62; mortgages, $2,425.93; promissory notes, $7,536.78; cash, $27.14; personalty, $4,000, and bricks unsold, $1,000.

(Toronto Star, March 28, 1933)

Back then a man’s home was his castle and he could do with his property what he wanted, but Margaret Diemal (Bert’s wife) and David Henry Wagstaff, son contested the will. They alleged Bert Wagstaff that he was unduly influenced by Margaret Paterson and Mrs. McCague. Essentially his wife and son told the court that these two scheming women had zombified Albert to the point where he, “had no will of his own but acted under their instructions.”

The Judge doubted that very much. He stressed the evidence given by J. R. Cartwright, one of Albert’s lawyers, and ruled that “he had no reason to think Mr. Wagstaff, although he knew he drank considerably, was not competent to make a will.” Justice Kelly found that “the relationship between the testator and his wife was and continued to be, strained and unhappy, due, I have no doubt, partly, at least to his friendship with other women and to some extent his mode of providing for her support. The result was a separation, he leaving his own residence in which his wife continued to live.” The family lost. And even though Wagstaff drank more than the proverbial fish, the judge deemed of “sound mind” when Bert made his will.

It is believed that two other women mentioned in the will were the mistresses of Albert Wagstaff, alderman and prominent manufacturer. He is rumoured to have “kept women” in each of the apartment houses he built, including the Louise and Albert on Dundas Street and the Avalon at Gerrard and Woodfield, but not the Vera at Wagstaff and Greenwood named for his daughter Vera.

David Wagstaff and his father did not get along, but that’s easy to tell even after all these years. Justice Kelly did not approve of David Henry Wagstaff because this son did not visit his dying father in the hospital until the very last. Given that Albert didn’t like the way his son worked in the brickyards and had fired him a number of times, the father-son relationship was on the rocks. The Judge found that this son was disrespectful : “David was so wanting in filial regard towards his father that he never called upon him of met until the Sunday, March 1931.”and had been threatening to his father. (Toronto Star, November 12, 1932)

Albert left the Alberta Apartments to his undutiful son David, but, in a mischievous move, he left the twin apartment building, the Louise, to a woman who was apparently his mistress. Margaret Paterson apparently got the Louise Apartments. If the relationship between Bert and Margaret Paterson was anything like the rumours said and his wife suspected (or knew), Albert was laughing from his grave.

The Avalon Apartments at Woodfield and Gerrard were left to Mrs. McCague, like Margaret Paterson another much younger woman (also no relation). An Islamic bookstore is there today, but one wonders if it is haunted by the ghost of Bert.

The Vera Apartments at Wagstaff and Greenwood were left to daughter Vera Sparks.

The brick pits on the west and east side of Greenwood park are clearly visible as well as a smaller brick pit on Coxwell Avenue north of the CNR line. Monarch Park is sandwiched between two former brick pits. The areas at the tops of all the streets east of Greenwood(Redwood, Highfield, Woodfield, Hiawatha, Craven and Rhodes) and south of the rail line were also brick pits, small but deep. Glenside Road was also a brick pit. Other small brick pits were scattered through the immediate area. The Devil’s Hollow from the rail line south to Gerrard was one big brick pit. Greenwood Park is built on a southern extension of the Devil’s Hollow brick pit.

With the Great Depression in the 1930s, the bottom dropped out of the brick industry. With little demand, only the Price brickyard remained at 395 Greenwood Avenue on the east side. It was now called the Toronto Brick Company. By that time the family brick plant was a thing of the past. After World War Two, when returning veterans married and needed housing, the demand for brick was unprecedented. Large plants using modern methods and machinery shipped bricks across the province from production centres, such as the Don Valley Brickyard on Bayview Avenue in Toronto.

Some photos of the brickyards on Greenwood Avenue follow:

But, as the saying goes it’s not over until it’s over and, in the Wagstaff, it wasn’t over until 1941. The Province of Ontario wanted succession duties out of the Wagstaff Estate that had not been paid when the will was settled on December 4, 1934. . The case went to the Supreme Court of Ontario (Re Wagstaff [1941] O.R. 71-79 ONTARIO [SUPREME COURT OF ONTARIO] ROACH, J. 18th FEBRUARY 1941).

The Succession Duty Act, R.S.O. 1927, ch. 26, secs. 8, 12 and 19, determined that the claims of those owed money by an estate (the creditors) should be paid before any succession duties were paid. But, in this case, the Wagstaff Estate was insolvent and there wasn’t enough money to pay everyone, including the Royal Bank. There was nothing left to pay the succession fees.

In 1934 the succession duties owed were $17,834.24, but over the intervening seven years interest had compounded and $25,395.46 was now owed. Most of the Wagstaff estate consisted of real estate. However, with the Great Depression, the value of that real estate had fallen from $244,094.62 to only $72,200.00. The valuable working brickyard was now the city dump and the apartment buildings were now in an East End that had become a slum in most people’s eyes. As the saying goes, “Location, location, location!”

The Province of Ontario did not get its money. Presumably the Royal Bank was able to put a lien on at least some of the property and get all or part of the money owed to it back.

http://caselaw.canada.globe24h.com/0/0/ontario/superior-court-of-justice/1941/1941onsc88.shtml

Albert Henry Wagstaff is gone and may be largely forgotten, but he left many clues behind him. Wagstaff Drive is named after as well as Bertmount Avenue near Queen and Jones. His father David Wagstaff had a brickyard there. Bertmount runs right through were Bert’s childhood home was. Albert Henry Wagstaff’s brick plant still stands on Wagstaff Drive. Part of it is home to the Left Field Brewery. Many of the houses in the neighbourhood were built with Wagstaff brick and some of Toronto’s well-known buildings such as The Distillery and Old City Hall (in part).