Craven — originally Erie Terrace.

The Ashbridge Estate stretches from Queen Street to Danforth Avenue with Ashbridges Creek flowing through it down to Ashbridge’s Bay. The east side of Greenwood Avenue and the land west of it to Danforth Avenue were incorporated into the City of Toronto in 1884 along with a narrow strip running along the north side of Queen Street to the Beach. The Ashbridges family passed down portions of the original estate to various descendents resulting in narrow strips of farm fields running north south from Queen Street, clearly visible on this map. They were east of Morley Avenue (later re-named Woodfield Road) to Coxwell Avenue. The farmers used deeply rutted, narrow farm lanes to drive their farm equipment onto these fields. The farm lanes ran beside the fences at the boundaries of the properties. When the properties were developed, a road network followed the pattern of the farm lanes and fences along the edges of these strips of farm field. Reid Avenue (now Rhodes Avenue), Erie Terrace (now Craven Road), Ashdale Avenue and Hiawatha Road. Redwood Avenue marked the eastern boundary of the 1884 extension of the City of Toronto. Glencoe Avenue (now Glenside) ran through a brickyard, later used as a garbage dump. It was not filled in and used for housing until after World War II.

Erie Terrace was developed as a “Shacktown”, outside of Toronto, in 1906, a year before the Ashbridge’s Estate was subdivided for housing. Now Craven Road, it has many tiny owner-built houses. Ashdale Avenue was not subdivided until later. No houses were built until later when its large lots were sold to more affluent buyers. This is why Craven Road only has houses on the east side. Ashdale Avenues bigger homes were built with their backs turned on disreputable Erie Terrace. The rowdy poor of Erie Terrace were often accused of trespassing. When the City of Toronto widened Erie Terrace in 1916, Ashdale’s home owners had nothing to gain. They lost some of their property and taxes went up to pay for the wider street. A deal was made. The City of Toronto put up a tall wooden fence was to keep the poor out of Ashdale yards and the . In 1923 the name was changed to “Craven Road” to eliminate some of the stigma attached to living there.

Shacktowns, like that on Erie Terrace, developed just outside the Toronto’s limits where municipal regulations did not reach. In York Township taxes were low and services non-existent. Speculators carved Erie Terrace up into tiny lots that even the very poor could afford. Edmund Henry Duggan owned four lots immediately east of the Ashbridge estate. Duggan was involved with the Toronto House Building Association which had developed Parkdale in 1875. One of the goals of the Association (later called the Land Security Company) was to allow low income families to own their own homes. Duggan’s holdings were laid out in tiny lots. Erie Terrace became a linear slum perched on a sandy gully. The east side of the street was densely inhabited while the west side, owned by the Ashbridges, remained undeveloped until later.

For many on Erie Terrace their first Canadian summers, 1906 and 1907, were the best of their lives, and the first winter was mild. Mostly young couples with children, they quickly got to know their neighbours. They had picnics; formed churches; enjoyed playing sports (especially soccer); and revelled in the woods and fresh air here. They co-operated to build each others houses.

Many of the houses in the neighbourhood had been built by the owners themselves when the area was outside the City limits. By the time of amalgamation, the area was well on its way to becoming a working class, low income street car suburb of Toronto. Some streets, particularly Erie Terrace, later called Craven Road, were densely packed with small houses, some mere huts, without running water or sewage, with contaminated wells and over-flowing outhouses, creating a public health nightmare. Some, including Toronto’s Medical Officer of Health Charles Hastings, saw these Shacktowns as epidemics waiting to happen.

But, in October 1907, a financial crisis smacked Shacktown down. Stock market players tried to corner the market on a copper company’s stock. When nervous people drew out all their savings, banks collapsed. The economy nose dived. Through no fault of their own, the Shackers were unemployed and broke. Unfamiliar with our weather, they began to freeze in unheated shacks as a fierce Canadian winter began.

In January, 1908, the Globe received a tip that people were starving. Their reporter was appalled by what he found: The sound of little children crying was yet in the wind that whimpers and blow over the land of tar-paper homes.

The Globe described Shacktown as having no government, no charities, men out of work, women worn out. Reporters found families without fuel or food, children with frost bite, and people critically ill without a doctor, medicine or even blankets. They launched the Shacktown Relief Fund on January 27, 1908. In the first day of the Globe’s appeal over $1,100 was sent. (Most factory male workers bought home about $7 a week.) There were eight Shacktowns so the Fund operated with eight districts. A manager in each district decided who received help. There was no welfare system to deliver relief except the churches. In most cases the district manager was an ordained Minister. The various denominations worked together, but Rev. Robert Gay of St. Monica’s Anglican Church was the manager here. (St. Monica’s Church was where the Gerrard-Ashdale Library is now.)

While other Shacktowns were receiving enough food donations to ensure no one was going hungry, in our neighbourhood the situation was initially forgotten until Robert Gay focused attention on Gerrard-Coxwell:

The weak spot in the situation is the east end shack district over the Don. A large part of it is within the limits and should be covered by the city organizations, but some part of it, several hundred houses in all, is in the township, and distress is said to be widespread there.

Women without winter clothes or boots, dressed in whatever they could find, trudged miles through snow banks downtown where they waited for hours in lines for food, fuel or clothing. Shacktown that winter changed how many thought about people in need. Many Shackers were quietly keeping “the stiff upper lip and suffering secretly behind tar paper walls. Robert Gay thought he knew what poor people were all about, but his preconceptions were shattered when he found people that he thought of as doing just fine now suffering from hunger without telling anyone. Some refused help. “What,” exclaimed on woman in sobs, “What would ma people in Scotlan’ think if they heard o’ this?”

They turned to each other. From the beginning, Shackers worked together, sharing the little they had. According to Gay:

I came across a case recently of a man and his wife who had scarcely any food and no money. The man was out of work, and the wife’s efforts to get work were of no avail. They were hard pressed, but were not so poor that they could not help those worse off than themselves. They took in two friends, a married couple from the city, who had been turned out by their landlord for failure to pay the rent, and together the household had been putting up a brave fight. It was a case of the poor helping the poor.

By February 11, 1908, the Relief fund had raised over $14,000.00. Toronto was generous. Most saw the Shackers as good people, thrown into poverty temporarily by a financial panic that they did not cause. And the new immigrants were British, white and Christian, at a time before multiculturalism when racism was open. Most of the people in our Shacktown were Scots, Ulster Irish or English. One charity administrator preferred Scots:

“We had more Scotch than any other nationality and they are known as a very thrifty people. We could tell you some awful tales about the English.” “What about the Irish?” asked Mr. Fred Dane, of the Irish Protestant Benevolent Society. “They are running the others very close,” replied Mrs. Grant.

By mid February 1908, the Relief Fund was meeting Shacktown’s basic needs. Spring would, bring not only flowers but work. The economy recovered as investors intervened to stabilize the stock market and banks. While jobs were one solution to the Shackers’ problems; annexation was another. Shacktown would get water, sewers, fire, police and paved streets if they joined Toronto. They voted to join the City. In 1909 the area became part of Toronto.

As the East End became urbanized, all too often Erie Terrace (Craven Road) was in the spotlight. Police caught Gladys Durant, a cross-dressing 15-year old girl, of 523 Erie Terrace trying to ride the rails to Texas. She was with two boys, Phillip Clare, aged 20, of 417 Erie Terrace and Chris James. A county constable arrested the trio in the rail yard in the west end. They were charged with vagrancy. Petty crime, like this with its hints of sexual misdeeds, occupied most of the journalistic attention at the time.

$7-THREE new; detached three-roomed houses, with hall, water, gas, Erie Terrace. Apply 664 Gerrard. Toronto Star, Dec. 17, 1910

Developers made fortunes selling lots, but when the City raised its standards for housing, requiring indoor plumbing and toilets connected to the City sewer system, many could not afford to comply and lost their homes. Some fought back. Frank Magauran appeared before the City Committee to protest against being charged $20.92 for sewage connection for his house on Erie Terrace. The work cost $11.89, but the City of Toronto charged everyone a flat fee of $18, plus a $2 connection charge, and 92 cents for overhead charges. Magauran claimed he should only pay $11.89, the actual cost. He lost. Globe, Oct. 23, 1911

LOST – Fox terrier, on Sunday morning, white with small black spots, dark ears, answers to name of Spot; tag number 1908, is a pet. Liberal reward No. 1 Erie Terrace, near Steele Briggs flower gardens, Queen east, phone Beach 596. Toronto Star, Oct. 23, 1911

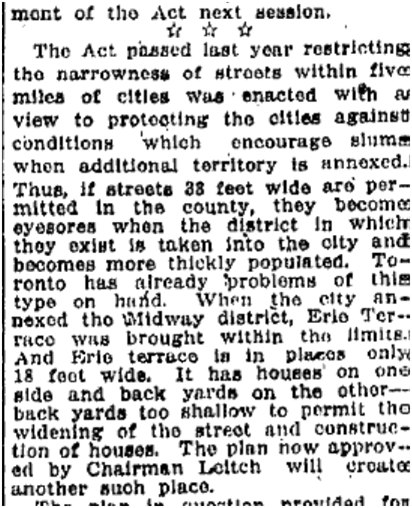

When Midway was annexed in 1909, Erie Terrace came into the City of Toronto. This narrow street, with houses on only the east side, stretched from Queen Street past the railway tracks. Unscrupulous developers cut this strip of land into tiny lots on which poor people built tar paper shacks and tiny houses, densely packed together, with no outhouses and no running water. This virtually guaranteed the contamination of their wells, the nearby creek and the ground water. Medical Officer of Health, Dr. Charles Hastings hated typhoid fever: it killed his little daughter. Pushed by Hastings, the City of Toronto passed a By-law requiring all houses in the newly annexed areas to have a flush toilet, a wash basin, a connection to City sewers and piped-in City water. Erie Terrace residents protested against being charged for sewage connections. They had no choice but to comply or leave. The Public Health Department closed their homes as unfit for human habitation if they failed to puts in “the modern conveniences”. Some protested, but other residents supported the City of Toronto.

The immigrants brought with them great dreams and great expectations, but, initially at least, their hopes were thwarted by the lack of amenities and services. These were services that these British urbanites took for granted. Their absence came as quite a shock. They demanded change as they met with their elected representatives in meeting after meeting. The records of one meeting in particular make clear their frustration. On December 2, 1911, the members of the Midway Ratepayers’ Association met with their aldermen in the Orange Hall on Rhodes Avenue.

It was a stormy, roily meeting of the members of the Midway Ratepayers’ Association who gathered last night in Rhodes Avenue Hall to batter with a load of complaints everyone aldermanic who had the courage to show himself within the doors, and at the same time it was a house divided against itself, between loyalty to and abuse of the reigning aldermen.” …”Half of those who live in that district’ he [local resident Mr. Gillespie] stated, “were too lazy to get out and work on a petition. They want water they want sewers, they want everything all at once, and they won’t work for it. I know of men on Erie Terrace who refused to pay the extra 37 ½ up to 75 cents taxes which would have entitled them to vote in the city, and yet they’re the ones who are doing the hollering because the aldermen don’t get them everything in a minute.

The residents wanted sewers, clean water piped in from the municipal waterworks, sidewalks, roads – in short, they wanted everything residents in older, downtown neighbourhoods had.

They wanted a subway built under the Grand Trunk Railway to improved road access from the neighbourhood to Danforth Avenue and Queen Street East. They wanted a walkway build under the railway track so that children could get safely from the streets north of the rail line to Roden School.

Alderman Sam McBride, who came down upon a special invitation, made an attempt to smooth the troubled waters, and explain to the Midway ratepayers just what position they occupied with respect to the rest of the city. Without censuring the district, he stated that the Midway should congratulate itself upon the city having taken it in considering the condition they were in when annexation was broached…

City politicians were not about to put up with ingratitude from Shacktown.

Alderman Chisholm responded: “You came here because this land was cheap. If you expect the city Council to put in waters, sewers, etc., and make your land valuable in a minute, you are mistaken, it can’t be done. Erie Terrace wants the city to bear the expense of its widening. Other streets don’t get such concessions, and as for your aldermen, we have far, far exceeded any promises we ever made to you.” (Toronto Star, Dec. 2, 1911)

In essence the politicians told the disgruntled ratepayers that they should be happy that the City of Toronto took the neighbourhood in at all given the bad shape it was end. Being told that they should be grateful for their lot and not complain did not go over well.

The Midway Ratepayers’ Association will take steps to have Erie Terrance improved. Globe, Jan. 6, 1912

The Works Department has a number of vexatious street problems on hand, and the committee made personal investigation into some of these yesterday. One is on Erie Terrace in the Midway. It runs north from Queen street to Danforth avenue and the width varies from 15 to 22 feet. There are small frame houses along one side and on the other are the backyards of houses which front on an adjoining street. It is proposed to add about ten feet to the width of Erie Terrace, taking the land from these yards.

But what then? Who will pay? The houses now built on the Terrace will have to pay their share, the city will have to pay its share, but what about the share which would ordinarily be paid by the properties on the opposite side of the street? The people whose back yards are taken get no benefit from the street improvement, for their residences front on another thoroughfare. Erie Terrace is their back lane and they don’t care whether it is ten feet wide or thirty-five. There is no room to build houses on both sides of the Terrace and the city will have to find some way out of the difficulty. Toronto Star, February 1, 1912

Cannot Get Sidewalk

Residents of Erie terrace want a permanent sidewalk on the east side of the street, but there has been no money reported for the work and it cannot go on. Toronto Star, March 26, 1915

Not everyone could afford to pay for the new improvements. But if they did not install a toilet, sink and bathtub, all connected the sewers, the Health Department would have them evicted and the Health Department did this — for the greater good.

When the City of Toronto widened Erie Terrace (Craven Road) in 1916, the municipality put up the fence. The people on Erie Terrace did not want the Ashdale Avenue people to use the widened road because the Erie Terrace people had paid for it and the Ashdale Avenue people had not. Back then if the City fixed your street up, paved it or put sidewalks in, the people living on the street were expected to pay for it. The charge was added to the property tax bill.

The people on Ashdale were only slightly more affluent than those on Erie Terrace, but Erie Terrace had a reputation much like Regent Park had until recently: crime, prostitutes, drinking, etc. So the people on Ashdale wanted the Erie Terrace people out of their back yards.

The City, meanwhile, did not want the Ashdale Avenue people using their now much smaller backyards for garages and sheds. The City had expropriated part of the Ashdale Avenue backyards to widen Erie Terrace. But what was left of those backyards didn’t have enough of a setback under Toronto Bylaws for building anything. So the fence is maintained by the City of Toronto despite periodic attempts to have it removed or partially dismantled.

I first started investigating Craven Road in 2002 when someone I knew from an America On Line birding board asked me if I could find out where Erie Terrace was, how his great grandfather died and why his great grandmother had to put the four boys in an orphanage and lose them. The solider who died was George Threlfall. He most likely died of influenza, in a precursor of the 1918-19 Spanish flu epidemic.

THRELFALL, Corporal, GEORGE, 6897, Royal Canadian Regiment. Died of sickness 1 December 1916. Husband of Emma E. Threlfall, of 283 Erie Terrace, Toronto, Ont. Grave Ref. S. F. G. 32.

The City of Toronto was now able to wring the money it wanted out of Erie Terrace and others in the East End now that virtually all of the men were working…most in the trenches.

LOCAL IMPROVEMENT NOTICE

Applegrove Avenue Extension Take notice that the Council of the Corporation of the City of Toronto intends to extend Applegrove Avenue at a width of 66 feet from Ashdale Avenue easterly to Coxwell Avenue, and intends to specially assess a part of the cost upon the land abutting directly on the said work, and upon certain other lands hereinafter mentioned, which will be immediately benefited by such extension. The estimated cost of the work is $27,000, of which…$7,103 is to be paid by the Corporation. [The rest of the cost was passed on to those living nearby on Applegrove Avenue, Erie Terrace, Morley Avenue, Hiawatha Road, Kent Road, Ashdale Avenue, Rhodes Avenue, and Coxwell Avenue.] Globe, March 29, 1918

While the War ground on, the Spanish flu hit, seemingly out of nowhere, spread from military base to military base and brought home by the returning soldiers. Older people seemed to have some resistance to it, but the young did not.

Dr. Hasting Forbids Conventions In City

Over 300 New “Flu” Cases are Reported at the City Hall.

List of the Deaths Increase Reported in the Schools – 50 Per Cent Absent From Some of Them

Dr. Hastings issued strict orders to-day that under no condition must conventions of any kind be held in Toronto until the present epidemic of influenza had died out.

There were forty new cases reported to the Department of Health this morning, while others will come in during the day. Up to date, 170 have been reported to the department. This, however, does not by any means represent the number of cases in the city, as there are over 300 cases in the hospitals alone….Up to noon to-day the following deaths from pneumonia and influenza had been reported since yesterday: … [Died of influenza] Walter J. H. Barber, 15 years, 206 Ashdale avenue. … Henry Hunter, 37 years, 589 Erie terrace. Martha Mitchell, 62 years, 4 Fairford street. …Rosie May Jones, age 37, of 19 Jones avenue. Agnes M. Ferguson, age 17, of 114 Logan avenue. Nellie McNelley, 201 Morley avenue…The epidemic of Spanish influenza in the Toronto schools is on the increase, according to information received by The Star this morning. In many of the larger schools as many as 50 per cent of the pupils are away, and in practically every school in the city, a large percentage is away sick. Toronto Star Oct. 11, 1918

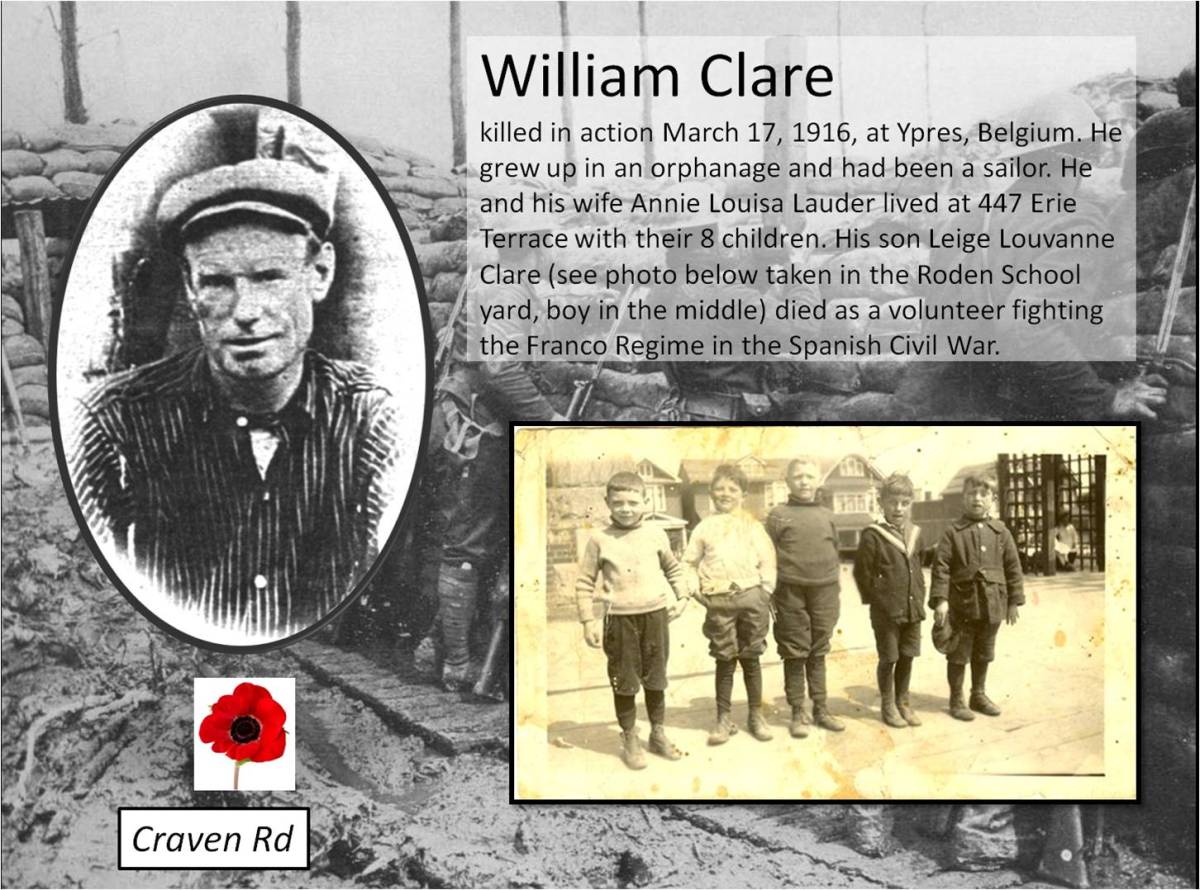

The First World War cut deep into the heart of Erie Terrace. World War I cost Toronto 10,000 lives. This odd, long street of tiny houses on only the east side contributed a disproportionate number of men to enlistment. Most were in the infantry and in the trenches of Belgium and France. Many did not come home or came home so wounded that they could not work. At the end of the Great War, Erie Terrace stood emptied of many of its men, a street of widows without adequate pensions or a way to make a living. Some had to give up their children, sending them to orphanages. Many women went into domestic service downtown or sought other jobs elsewhere and left. Some remarried. Some stayed. The emptied houses quickly filled with returning veterans desperate for homes in a post-war housing crisis.

Her neighbours built and paid for a new house at 617 Erie Terrace. Toronto Star, Jan. 16, 1919

It was indeed a sad home-coming for W. T. Smith, of 113 Erie terrace. While there was happiness on every hand – mothers, wives, sisters, sweethearts, and kiddies hanging on to their loved ones – Smith had nobody. He lost his five-year-old girl Gracie in January, 1917, from bronchitis, while he was overseas. It was his only child. Smith went out with Lieut.-Col. H. A. Genet’s battalion from Exhibition Camp in November, 1915, and was transferred to the A.S.C. in 1916. He broke down at the front, and was twice operated on for a serious illness last October, and after recovering was found to be unfit for active service. Toronto Star, Feb. 18, 1919

In 1919 there were plans to build an electric light rail line (a hydro radial) through Toronto from the east in the Morley Avenue area. Erie Terrace (Craven Road) was considered a likely route, but the plan fell through. Toronto Star, Sept. 25, 1919

Men and women turned to rebuilding their lives, having babies, raising their children and entering them in baby contests.

Building continued after the War, including on the much loathed Erie Terrace which now had a reputation for crime and filth similar to modern welfare ghettos. Builders constructed middle class housing, known as “villas”, but also many working men’s cottages in the “Swiss”style. Globe, April 12, 1921

The East End was heavily unionized, against prohibition, and voted left which did not prevent many from, at the same time, being active in the Orange Lodge. Here is a listing of some of the Unions based in the East End drawn from 1921 Might’s City Directory:

Boilermakers and Iron Ship Builders and Helpers International Brotherhood. Local No. 128, meets first and third Fridays, Labor Temple, J. V. Gormly, 84 Alton ave, secretary

Carpenters and Joiners U. B. Mill Hands and Cabinet Makers, Local No. 1820, meets every Tuesday, Labor Temple, T. Jackson, 529 Pape Ave, pres.; Chas. Jarvis, secretary

Carpenters and Joiners U. B., Local No. 2639. meets alternate Mondays, Labor Temple, E. Gregory, 431 Leslie, secretary

Engineers, Machinists, Millwrights, Smiths and Pattern Makers, Branch No. 1090, meets second and fourth Thursdays in Masonic Hall, Gerrard e, and Logan ave. J. Hobson, 407 Erie Terrace, secretary

Glass Workers (B. of P. & D. of A.). Local 575 meets first and third Friday it Labor Temple, B. J Bnb, 92 Jones at, secretary

Glass Worker American Flint, International Union Local No. 45, meets first Saturday, 793 Gerrard e W Phillips. 388 Carlaw ave, secretary

Glove Workers’ I. U.. Local No. 8, meets second and fourth Mondays, Labor Temple, C. Haddleton, 79 Empire ave, secretary

Mailers Int. Union. Local 5. meets first Sunday, Labor Temple, Robt. Gardiner, 11 Cherrynook Gdns.

Waiters and Cooks Local No. 300, meets second and third Thursdays 10.30 a.m., Club Boom, 301 Dineen Bldg., H. W. Brooker, secretary, 88 Prust ave.

Everyone in the neighbourhood wasn’t as saintly as Principal Craven. Petty theft and break-ins were perpetual in the East End. The poor usually stole from the poor. Often people stole clothing such as shoes or even underwear from the clothesline. Yet most people were hard working, when they could work, shared the little they had, and obeyed the law even when the law was unjust or indifferent to their situations.

CHARGED WITH THEFT William Huff, 617 Erie Terrace, was arrested Sunday afternoon by Detective Clarke on a charge of theft of automobile tires. On searching Huff’s home the detective claims to have found two stolen tires. A. Slighton, 175 Wolverleigh boulevard, and Charles Skeets, 130 Rhodes avenue, are the complainants. Globe, Oct. 15, 1923

Craven Roaders had a sense of their rights and supported each other. When an Member of Parliament made a casual racist remark, it was challenged.

But life on Craven Road in the Dirty Thirties was almost as bad as the winter of 1907 to 1908 when people actually did starve. The East End became associated with hard times, overcrowding and crime, an association that did not lift until the late 1990s.

Erie Terrace/Craven Road forever.