Everything changes, nothing remains the same. The Gerrard-Ashdale neighbourhood grew up on the farm fields to the north and east of Leslieville just before the Great War. It was very different from the neighbourhood of today with the Indian Bazaar, the Tea N’ Bannock cafe with its native food, and the eclectic mix of old and new. However, it was also very different from the old Leslieville that grew up around George Leslie’s nursery at Queen and Jones Avenue. We are different too, different in our standard of living, our beliefs, our thoughts, from our grandparents and great-grandparents, but we are the same too. Let’s explore the difference and think about how our neighbourhood of 2017 came to be through the great tragedy that was World War One or “The Great War”.

This new neighbourhood was no longer based on the old industries: pigs, flowers and bricks or in other words, livestock and abattoirs, market gardening and florists, and brickmaking. This new neighbourhood was booming. I call it the “Gerrard-Ashdale neighbourhood”, but it had many names, none of which really seemed to stick. It was called “Shacktown” by those who looked down at poor immigrants who built their own little houses out of whatever they could scrounge. Some called it Midway because it was mid way between the City of Toronto and the Village of East Toronto and was part of York Township until Toronto annexed it. Others called it the Roden Neighbourhood after the Roden School. The Roden School, first called the Ashdale School, was here before other services and even before the area joined the City of Toronto. It was a focus for the community. After the neighbourhood joined Toronto, some people called it East Riverdale.

Whatever it was called, it was overwhelming British, composed of immigrants from the big urban centres: London, Manchester, Liverpool, Leicester, Birmingham, Glasgow, Belfast, etc. It was so very British that some referred to it as a “Little England” even though many of the immigrants were Scots or Ulster Irish with a handful of Welsh. It was overwhelmingly Protestant, mostly Anglican or Presbyterian, by faith and working class through and through.

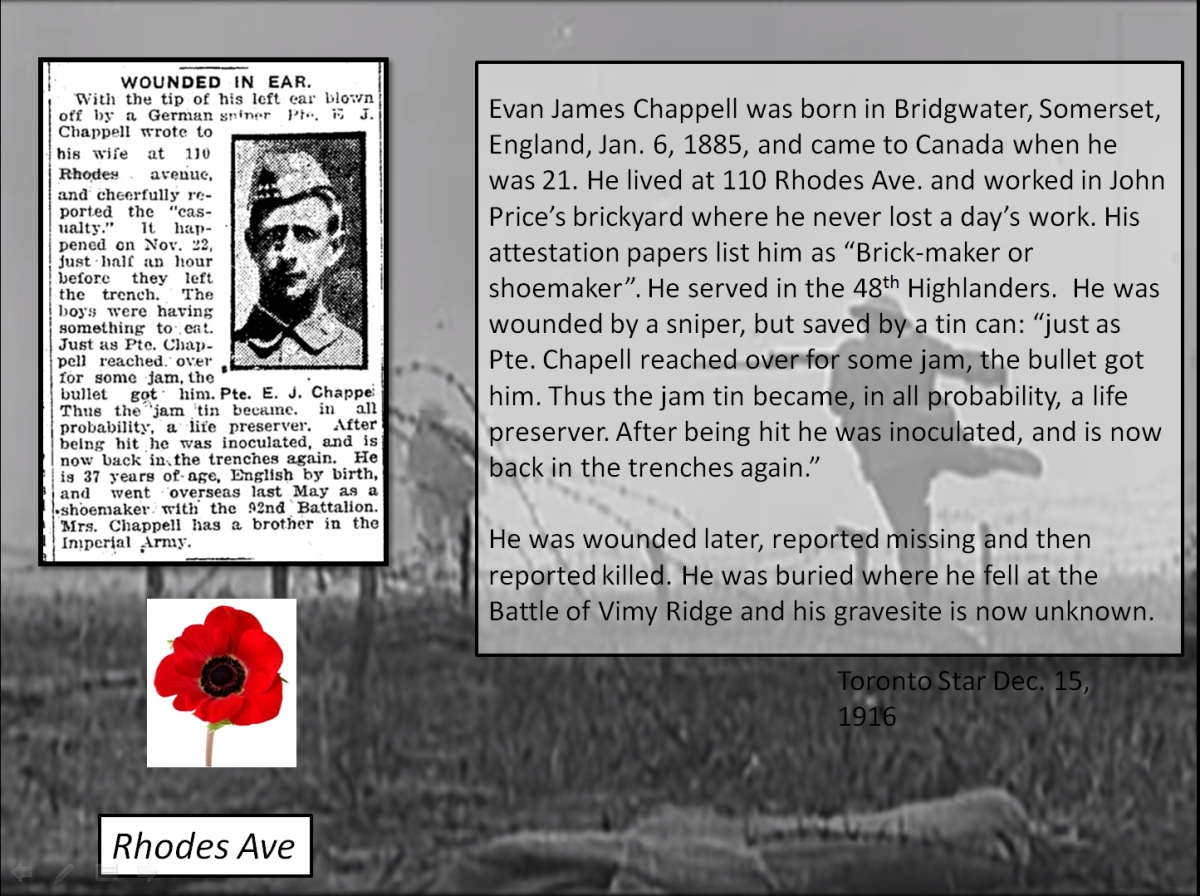

Many of the women had been servants; the men, factory workers. But there was a pattern to settling the flat, empty farm fields after the Ashbridges sold it for development. Even while the streets were being laid out, tradesmen came, knowing that their skills as carpenters, electricians, plumbers, plasters, painters and jacks-of-all-trades would be in high demand. Brickmakers came too, drawn by the brickyards on Greenwood Avenue. Many were from Somerset lured here by the Price brothers, brickmakers, who themselves came from Bridgwater. Their houses, mostly built by themselves, sprung up, scattered here and there, like signposts of things to come on the empty pastures. Along with them came entrepreneurs: butchers, bakers and above all, corner grocers. Grocery stores were often built at four corners like Coxwell and Gerrard or Greenwood and Gerrard before any other buildings.

Then came the factory workers and the streets filled up with five-room houses, mostly bungalows, affordable. Many of the men belonged to unions and voted Labour. Unions. They came to better their lives, not die on the fields of Flanders or France.

The area grew up higgledy-piggledy. There was no town planning. This flood of urban immigrants found no services: no water, no sewers, no fire department and virtually no police. The schools were schools inadequate, soon overcrowded with pupils forced into portables. There was no library. Government at all levels was reactive, not proactive, bringing 19th century thinking into the 20th century. Taxes were low but City Hall only reluctantly moved to offer services. People had to “go it alone” or rely on their families. Most did come as families. Usually a father, son or brother came first and a year or two later the rest of the family, often sponsored with their passage over the Atlantic paid for by “the British Bonus”. The nucleus of the typical family was a young couple in their early twenties with several children, but often relatives joined them. For them, the saying, “Blood is thicker than water” was all important. They had to rely on their family because family was the only safety net. Many had endured “the Poor House” in Britain and they wanted so much more. That’s why they came and soon built a community that reflected their dreams. Gerrard was lined with butchers, bakers, confectioners, greengrocers, tobaccionists and cinemas. They even had a vaudeville hall, the Classic Theatre, now the Centre of Gravity, at Highfield and Gerrard.

It was British. It was working class. It was Protestant and it was very different from today. But the Great War undermined the very Empire they believed in and the hierarchical social order they came from. It shattered dreams, wiped out old ways and in its suffering were the seeds of the neighbourhood we know today.

I am asking you to approach this with binocular vision. One lens of the binoculars captures Then, that is 1914 (the map on the right is the neighbourhood in 1914), and the other captures, Now, the neighbourhood in 2014. Together they bring a focused view that enables us to look forward to something else: the Future. History, to be meaningful, is about how we got from then to now and can stimulate thought. The writing of history is not a neutral, deadening drudgery but an adventure in thought. Solid historical writing explores who we are and how we came to be. Implicit in this is how we might come to be.

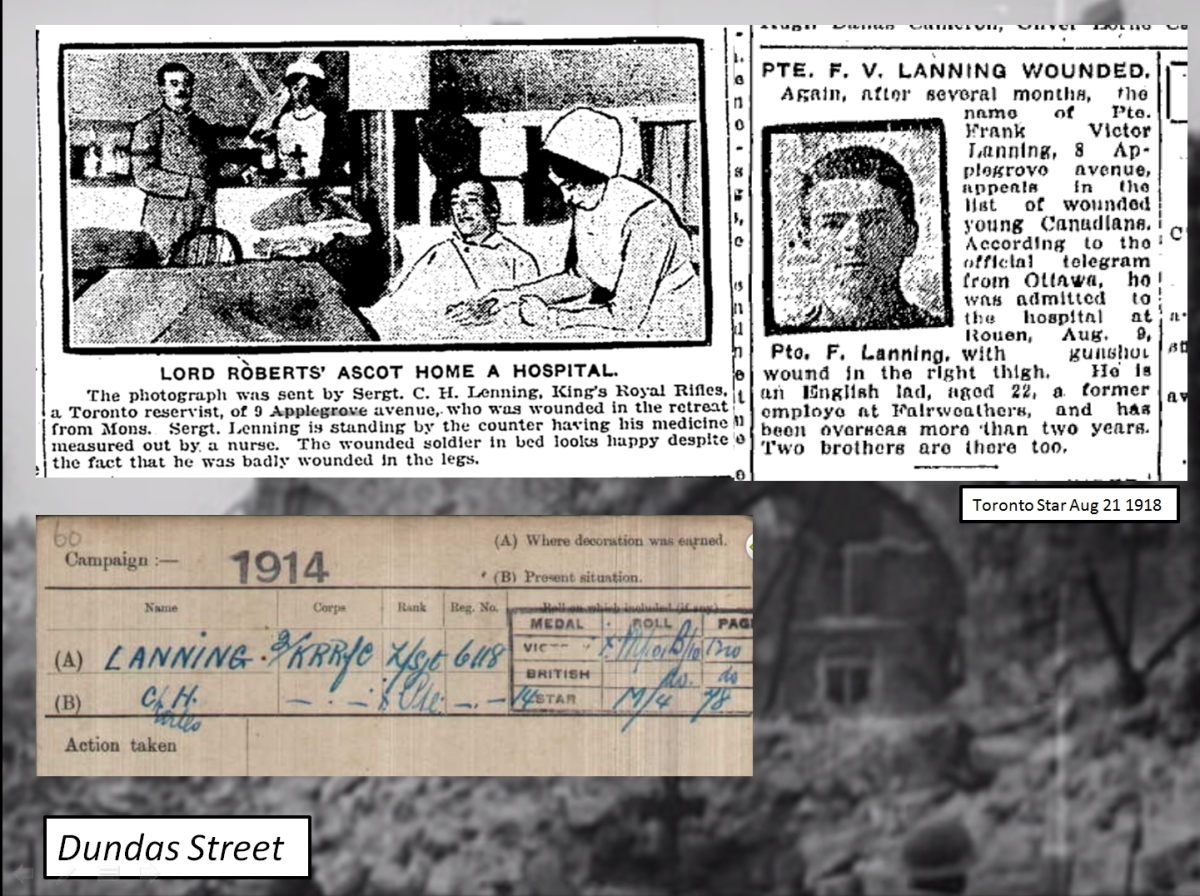

When looking at the map, note that the names of the streets have often changed. Woodfield Road was Morley Avenue. Craven Road was Erie Terrace. Rhodes Avenue was formerly Reid Avenue. Gainsborough was Eighth Ave and Cannon. Eastwood was Small Street, etc. Dundas Street East did not even exist until the 1950s when it absorbed a number of smaller streets like Doel Ave. and Applegrove Ave. Glenside was a garbage dump that didn’t get built on until the 1940s.

World War One changed life here forever. While historians usually paint with broad strokes as if only governments, generals and industrialists mattered, in the end it all came down to individuals, families, friends. This neighbourhood is a microcosm of the country, except that this neighbourhood and Earlscourt had exceptionally high enlistment and casualty rates, almost as high as First Nations reserves. Men and women settled here because of the proximity to industrial jobs. This working class neighbourhood was created in a real estate boom that began in 1900 and collapsed with economic recession in 1913. Just before the war many men lost their jobs and factories idled with no demand for their goods. Toronto had been building a substantial industrial base that by 1913 included a large iron and steel industry.

The First World War rescued Toronto from a depression. During the War plants along Carlaw Avenue and in the new industrial lands on the waterfront and Eastern Avenue focused on producing war materials, especially explosives and artillery shells. To keep up, factories were forced to hire women. World War One gave women jobs and the vote.

So, I would argue, that while we live in the same physical spaces, we live in a very different social space.

- They had relatively low taxes, but few services. We have higher taxes, but enjoy many more services. There were much lower expectations of government then. Canada had no income tax until World War I. Most Canadians had a very limited view of the responsibilities of City government (police, schools, roads, fire, nuisances,) but this was changing rapidly and the new urban British immigrants expected more. Public health, town planning, social work, sewers, water filtration, electricity, building permits, housing, and parks all came to be expected from government. In this neighbourhood, intervention at even the most basic level was crucial as the ground water was polluted by the privies or outhouses. At first, the City had water trucked in, but sanitary sewers and piped in, clean water were essential to avoid epidemics of typhoid fever and other water-borne illnesses.

- Transportation was based on the street car. These were even called “street car suburbs”. There were few private cars and most houses did not have driveways. Just after the Great War, the Toronto Transportation Commission (today’s TTC) took over the private streetcar companies to provide cheap transportation. Before that (and even afterwards) many people walked to their jobs in factories on Carlaw and Eastern Avenues. When the neighbourhood began there were still horses and wagons or buggies. But the demand for more and better transit was constant.

- People’s standard of living was much lower than now. Today the neighbours are increasingly, affluent middle-income professionals with young families. The price of housing is putting the neighbourhood out of reach of many as “Location, Location, Location!” works its magic. But then it was working class, blue-collar and even very poor. Even chicken once a week was a treat, giving meaning to the politician’s promise of, “A chicken in every pot”. There was a lot of poverty and, for some, hunger. People feared the Poor House or Work House where unemployed men and women, orphans and pensioners were warehoused in degrading conditions. During the Great War many widows lost their children as they were no longer able to feed them. There was no effective strategy to deal with the huge loss of life. Widows were left with totally inadequate pensions or no pensions at all and had to rely on the Patriotic Fund, which was not government-run but a private charity. Those needing held were vulnerable to the whims of the first social workers, the so-called “friendly visitors”. Relief was haphazard and discriminatory. World War One brought higher taxes and high unemployment when it ended in 1918 and “the Boys” came home, leading to social unrest and strikes. But other differences were less dramatic. More people lived in smaller spaces as they doubled up in the housing shortage of the Great War. There was less privacy and less expectation of privacy.

- Development costs downloaded on homeowner: Costs of development shared between homeowners on a street at the city. The City of Toronto expected homeowners living on a particular street to pay for improvements on that street: sewers, paving streets, sidewalks, etc. Although some residents were renters, most were home owners. But home ownership declined later over time as neighbourhood declined. By the 1930s the neighbourhood, after the stock market crash of 1929 and throughout the Great Depression, was in desperate shape as industries shut down and unemployment soared.

- This was a Little Britain not the Little India it became in the 1970s. Many men and women here belong to the Loyal Orange Order. People really did believe in the superiority of “the Anglo-Saxon race” and took the inferiority of others for granted. They believed in the King and Empire and, at least in 1914, most people in this neighbourhood identified more with Britain than Canada and even people born here thought of themselves as British. Society was religious, and specifically, Christian not secular. It was certainly not tolerant of other faiths. There was a great deal of missionary zeal, sending men and women to Africa, India and China to convert the pagans. At home, anti-Catholicism and anti-Semitism were typical. This was not a multi-cultural society by any means. Immigration policies were overtly racist and exclusionist.

- There were more immigrants here than native-born Canadians. The skills of these British immigrants were in demand. Tradesmen (carpenters, plumbers, electricians, plasterers, etc.) poured into the new suburbs on the edges of Toronto, pioneering settlement on the newly laid out side streets. These workers were heavily unionized and working class.

- The role of women was changing. Working class women, especially those from Britain’s big cities, had always worked outside home. They had never been ladies, though some aspired to being “lady-like”. Instead many of them were servants or worked in factories, particularly in the garment trades. Their labour outside the home helped maintain the family as working men and women were vulnerable to of seasonal unemployment and lay-offs, as well as periodic downturns in the economy. Having a strong family was key to survival. There was no real safety net so everyone worked, even kids. While women had worked outside the home, they had no direct voice in politics and no vote until World War One. The War opened up many opportunities for women in new roles as the men were away fighting.

Reid family, photographer unknown (Morley Ave. now Woodfield Road). Percy Reid in back, in Canadian army uniform. Though older men did enlist, this army was by and large made up of young men, teenagers and men in their early twenties.

The world of 1914 was one of great hopes, dreams. Working class people had good, affordable housing. The bungalow, often built from kits or pre-fabricated, was designed specifically for working class families. Land in Gerrard-Ashdale was cheap. People had a chance to buy their own homes, work hard, get ahead and educate themselves and their children. Many had good jobs in a growing economy. Their hopes were the immigrant dream: a chance to get ahead for yourself, but, if not yourself, your kids. The same dream held true after World War Two when Italian and Greek immigrants came to the Danforth and settled along Gerrard and its side streets. The dream was still with us in the Sixties when men and women began to come from the Caribbean in larger numbers to live and work here. When the first South Asian people came to Gerrard-Ashdale in the 1970s, the dream burned bright here.

In early August 1914, the Great War began after the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo. Families, like the Loves of Ashdale Avenue or the Reids of Woodfield Road, expected their husbands, sons or brothers to be home by Christmas.

World War One blew families apart literally. The dream became a nightmare for many as this neighbourhood, full of young immigrant men and their families, lost disproportionately heavily in the trenches. The majority of recruits went into the infantry where the losses were very high due to the combination of outdated military tactics and deadly new technology like machine guns and gas. The armies fought a war of attrition, hoping to kill so many of the enemy’s soldiers that the opposing army could no longer fight. German machine gun fire cut down lines of British, Canadian, Indian and other soldiers as if they were blades of grass under a mower. Soldiers’ lives were cheap. They were “cannon fodder”. The generals in 1915 did not trust the relatively untrained and undisciplined recruits not to break under fire. So they ordered them to walk slowly in lines into overwhelming gunfire. These tactics were to change by the end of the war when the Canadian army reorganized and the generals recognized the need for small groups (platoons) and lower ranks (non-commissioned officers and privates) to both know what was going on and to take initiative. By the time of Vimy Ridge, every soldier knew what his and his unit’s goals were, how to achieve them, and what to do if he faced an obstacle such as a machine gun nest or a bunker. They worked closely together, living in dreadful conditions with rats, mud and rotting corpses of the unburied dead and grew close together as chums or pals.

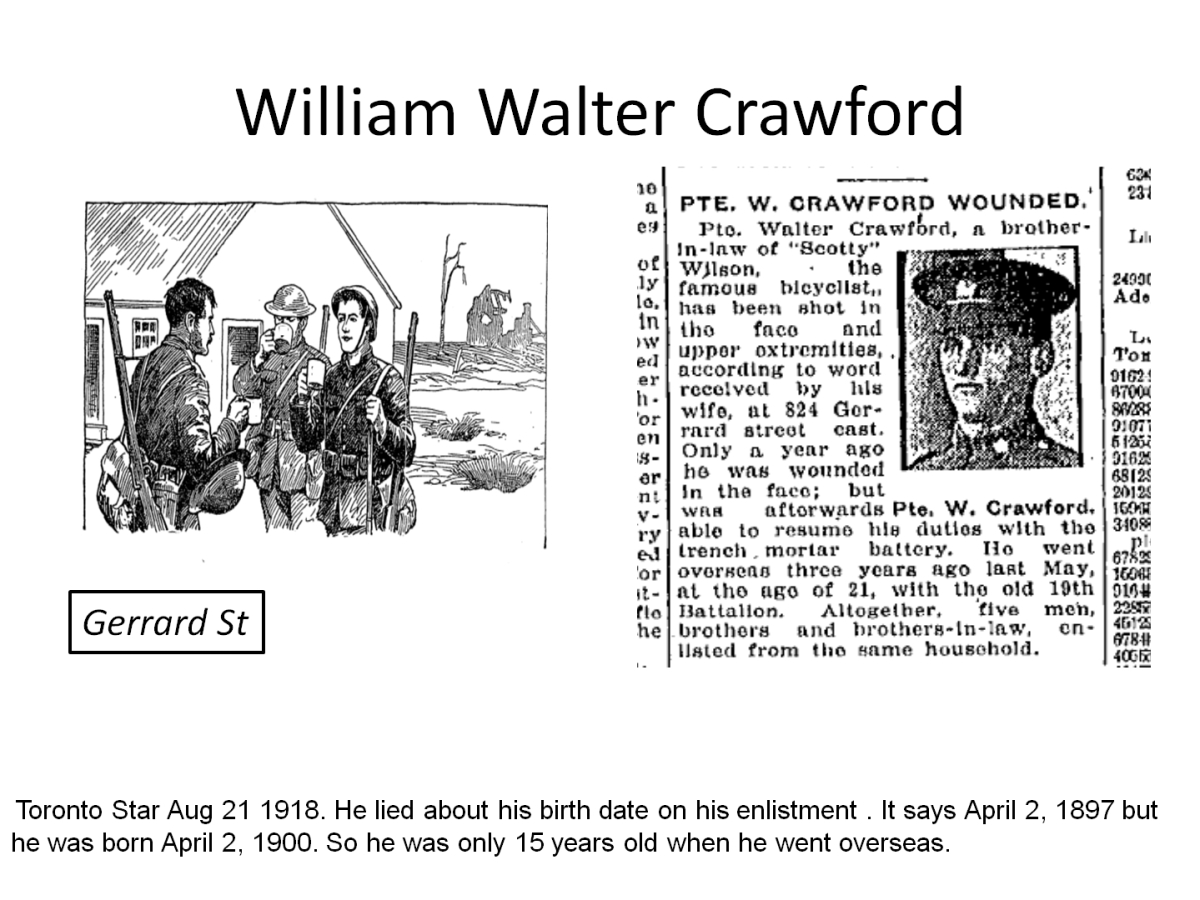

John King is at left with his wife and children. The First Contingent of Canadian soldiers to go overseas were poorly equipped with webbing/equipment belts that fell apart when they got wet, shoddy boots and Ross Rifles that jammed when muddy. They were even more poorly trained and ill-equipped for war in every way but courage and enthusiasm.

There were then more than 2,000 Canadian Lodges. Toronto World, June 10, 1918.

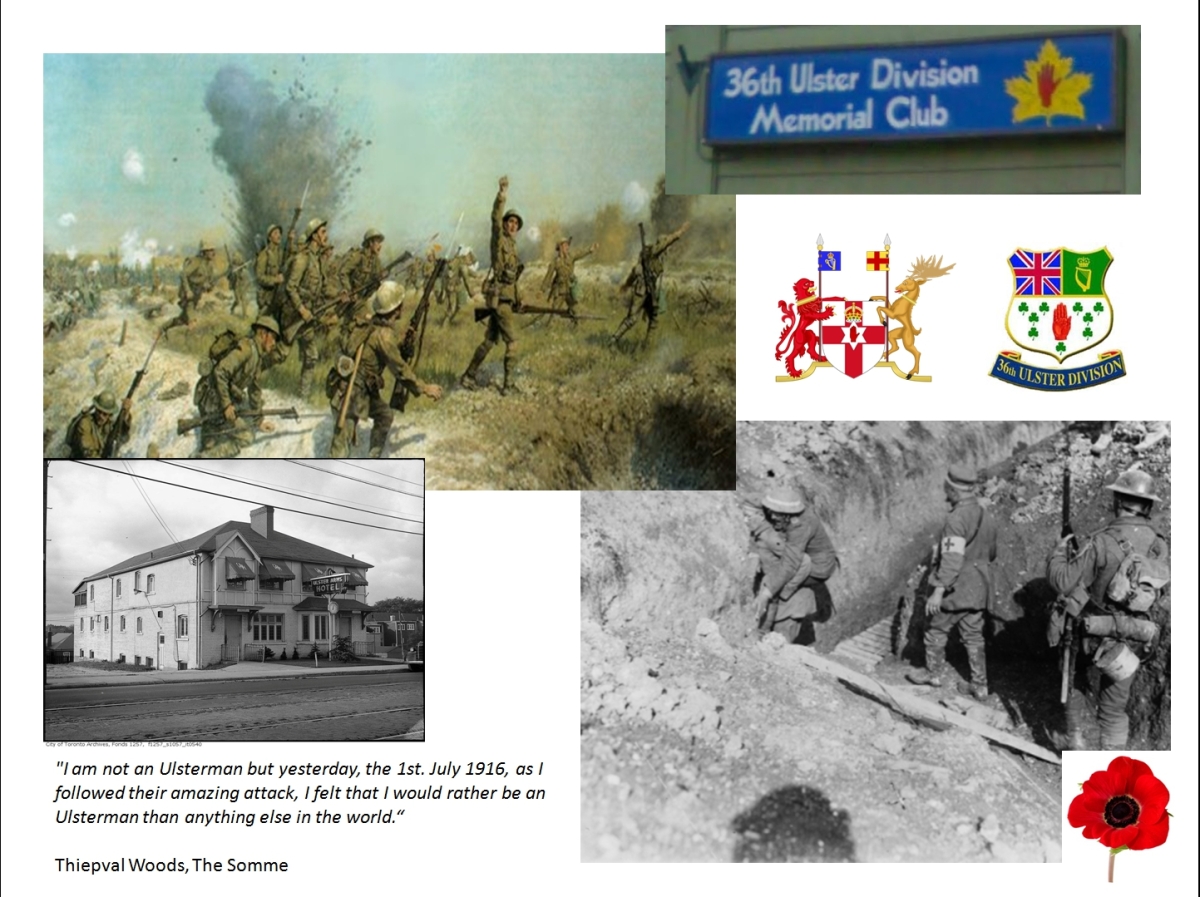

Leslieville’s social life was dominated by Orange Order during the Great War and for many years to come. Ulster, the northern most provinces of northern Ireland, were inhabited by a strong Protestant majority and stayed part of the United Kingdom when Ireland became independent. Dian Hall on Rhodes Avenue, now a mosque, was an Orange-owned building that served the area as a community centre throughout the 1920s and onwards while the Orange Order remained a strong presence.

The Ulster Division, composed primarily of Orange Order members, distinguished themselves in World War I, particularly in the Battle of Thiepval (part of the Battle of the Somme). To their left flank was the 29th Division, which included the Newfoundlanders. (Newfoundland was not a part of Canada until 1949). For the Newfoundlanders at Thiepval it was a disaster. In less than 30 minutes they were mowed down. 801 men went “over the top” into action. The next morning at roll call only 68 men were left unwounded. The 36th Ulster Division fared far better, largely in part because their commanding officer ignored the order to march slowly in long lines into battle.

On 1 July, the Ulstermen ran quickly forward, taking cover where they found it, darting from shelter to shelter, firing at will. They achieved their objectives, but had to fall back in the evening because they were far ahead of the other units of the British army, without support and vulnerable to enfilading fire. They were running out of ammunition and supplies. Their bravery was outstanding and their battlefield tactics were singularly successful.

The battle of the Somme ended in mid-November. The British had 420,000 casualties, the French 195,000, and the Germans 650,000. It was a bloodbath.

James Laughlin Hughes, educator, author, elder brother of Sir Sam Hughes. Throughout his life James Hughes was active in the Orange Lodge. He wrote a number of educational books, plus several volumes of poetry, including Songs of Gladness and Growth (1915) and In Nature’s Temple Shrines (1921). Sir Sam Hughes was the Minister in charge of Canada’s war effort. He was eccentric, bombastic and even the King of England is reported to have said that Sam Hughes was “off his horse”. He is credited, however, with keeping the Canadian Army together as a fighting unit and not allowing the Battalions of Canadians to broken up and sent to British army units as reinforcements. This was to be crucial to Canada and an important part of our heritage. Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden eventually sacked Sam Hughes. Sam Hughes had become very unpopular due in large part for his refusal to replace the Ross Rifle. The Ross Rifle, though excellent for sharp-shooting, jammed so easily that soldiers literally threw it away and picked up Lee-Enfield rifles from the bodies of dead English soldiers.

Gerrard-Ashdale’s Orangemen enlisted eagerly in 1914 to fight for King and Country. Orange enlistment was far out of proportion to their numbers in the population and Orange Lodges suffered dreadful casualties, losing many members. Nevertheless, the Orange Order reached its highest point in the 1920s with more immigrants from Britain. Those lodges included:

Eastern District.

1.Dian. No. 2054, meets Dian Orange Hall, 182 Rhodes Ave., second & fourth Fridays.

2.Maple Leaf, No. 455, meets at Oddfellows’ Hall, Queen & Broadview Ave., fourth Friday.

3.Prince of Orange, No. Ill, meets at Masonic Hall, Gerrard & Logan, third Tuesday.

4.Torbay, No. 361, meets at Playter’s Hall, Danforth Ave., second & fourth Thursday.

5.Riverdale, No. 2097, meets Armstrong’s Hall, Pape & Badgerow Avenues, first Friday.

6.Sproule, No. 2253, meets first & third Thursday at Dion Orange Hall, 182 Rhodes Ave..

7.Lt. Col. J. H. Scott, No. 2416, meets second Monday, Masonic Hall, corner Gerrard & Logan Avenues.

Despite racism, explicit and covert, the Government felt no hesitation to call on all peoples to fight in what some called “a white man’s war”. First Nations responded wholeheartedly. Many communities sent a third or more of military-aged men to fight overseas. The 114 Battalion was made up of recruits drawn from the Haldimand-Norfolk area of Southern Ontario, including hundreds of men from the Six Nations at Brantford and the Mississaugas of the New Credit at Hagersville.

Black people lived in the Gerrard Ashdale neighbourhood in 1914 and contributed to the war effort in many ways even though some recruiters refused to allow them to enlist, saying that, “It was a White Man’s War”. They have been rendered invisible in many histories. As it was, black soldiers were often considered too unintelligent to be allowed to fight and were consigned to construction units. Jazz, however, was the popular music of the time and good bands were always welcome.

Historiography, the study of history, requires a critical eye and an open mind. Jones should have been awarded a Distinguished Conduct Medal. There is no doubt that if he had been an Anglo-Saxon Canadian, he would have become a celebrated hero.

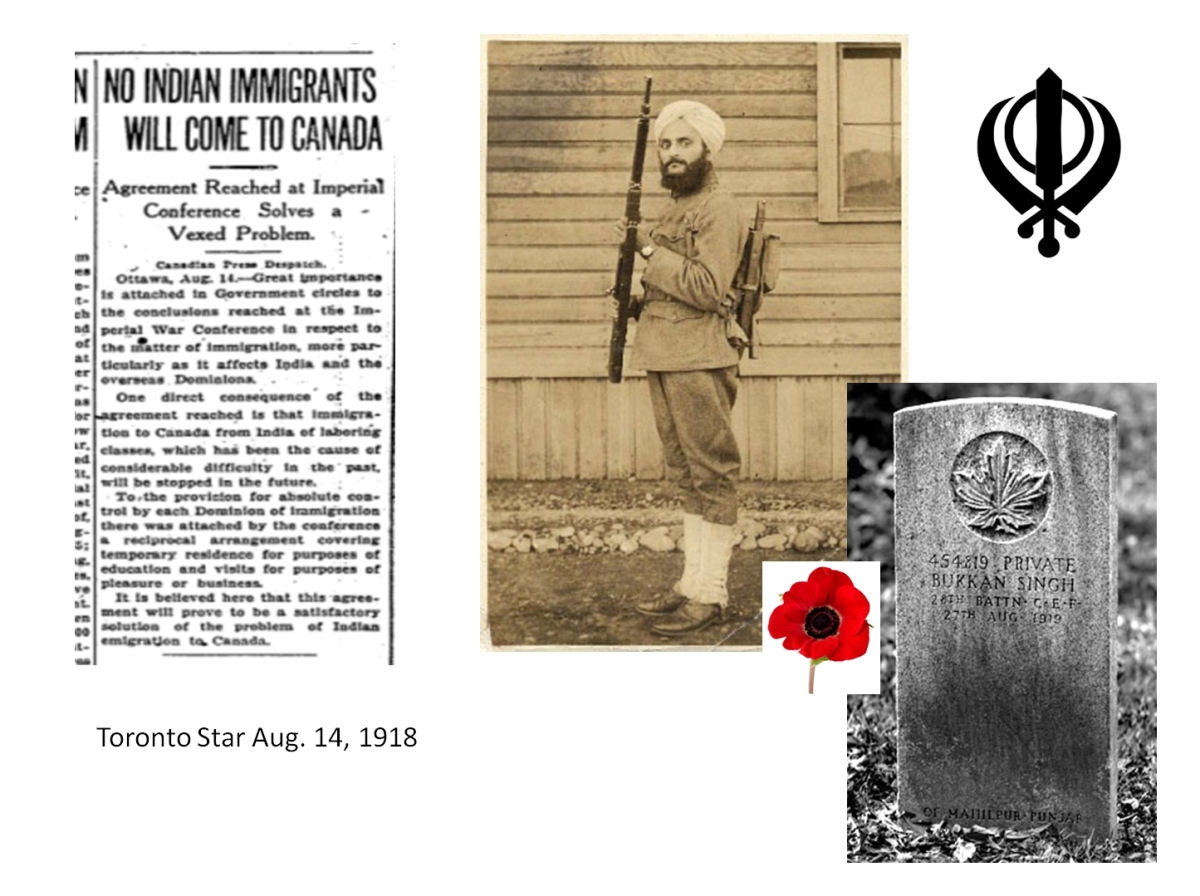

Britain drew on the Empire to fight in the trenches. Men poured in by the hundreds of thousands from what are now the countries of India and Pakistan… though they were not welcome as immigrants in Britain or the Dominions of Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Sikhs, Muslims and Hindus fought and died on the fields of France and Flanders.

They fought but not welcome to live here or become citizens. Private Bukkan Singh is buried in Kitchener/Waterloo. Canadians rioted against South Asians who landed in Vancouver and a deal was made with the British government to keep South Asian immigrants out of Canada. Similarly while Chinese Canadians fought, they were not welcome either. Though many of our houses were built in this period and the street network laid out then still exists today, social attitudes were very different. Though the same physical or geographic space, it was a different social space. The Canada of 2014, it goes without saying but must be said, is not the Canada of 1914. But the seeds of 2014 were there in the First World War which wrecked the very Empires it was fought to save and fed the hunger for human rights, dignity and independence around the world.

Leslieville had three gum factories. Soldiers were particularly fond of Wrigley’s chewing gum. Chewing gum as “a tonic bracer for nerves”. Smoking cigarettes or drinking whiskey before “going over the top” into battle also helped relieve tension. Airplanes never dropped gum to soldiers like this, but soldiers did value gum for a peculiar reason or so I have been told. Gum came in nice sterile little packages that could be softened by hand and used as an emergency plaster to plug a wound.

The first casualties from Canada were not in the Canadian Army. They were immigrants from Britain who had served in the British Army before the War. When Britain declared war on Germany and Austria, these men were part of Britain’s reserve army. Reservists returned to Britain, often at their own expense, to rejoin their regiments. The Grenadier Guards were an elite unit and suffered heavy casualties as the tiny British Expeditionary Force (BEF) retreated before the huge German Army flooding into neutral Belgium. The BEF was a highly trained force of professional soldiers but was decimated in 1914. Britain had to rely after that on an unprofessional volunteer army. Recruiting stations were overwhelmed by volunteers — so much so that in the first week of August 1914 the lines of men waiting to join up were sometimes over a mile long.

Toronto Star Nov. 7, 1914. Such open reporting did not last long. Censorship soon prevented such graphic descriptions of casualties, not wanting to demoralize people at home or discourage recruiting.

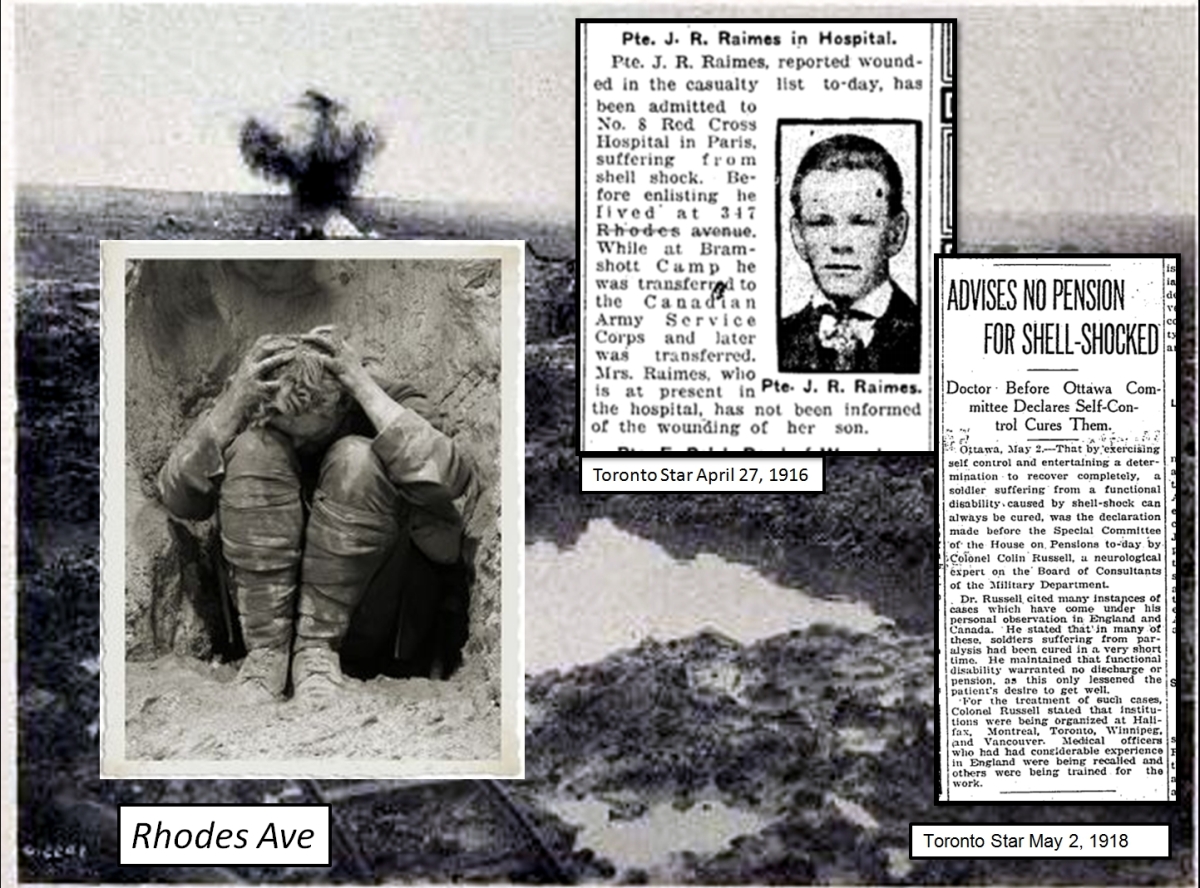

In a nation of 8 million people, more than 620 000 served in the armed forces. Of those, about 67 000 died and another 180 000 were wounded, shot, cut to pieces shrapnel, poisoned by gas, bayoneted, bombed, blinded. Some were sent back after severe wounds, sometimes again and again. This does not include the mental and emotional casualties, the shell-shocked, maddened, suicidal, alcoholic.

People here and in Britain enlisted in “Pal’s Battalions” made up from men of the same neighbourhood or the same social circles. Athletes like the Dibble brothers joined the Sportsman’s Battalion from Toronto. It was as if the greatest hockey legends of today went off to fight. The Dibbles were stars.

The Battle of Neuve-Chapelle is aptly named as it provided a new role for Canadian troops who had just arrived from Salisbury Plain, England, where they had been training. While not a large battle, it was not without significance from a Canadian perspective, in that it was the first time that the Canadian Expeditionary Force had been fully involved in action with the enemy.

http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/firstworldwar/025005-1100-e.html

As the War ground on their was great pressure to enlist. The initial naivety did not last long. Throughout the war ordinary people had a very good idea of just what was going on in the trenches. Letters from the Front slipped through. Wounded men returning from Europe spoke to family and friends. The word got around, but men still enlisted.

However, as time passed, the need for replacements to go overseas mounted and the supply diminished. Pressure mounted. Military recruiters went door-to-door demanding to know why an able-bodied man was not in uniform and “encouraging” him to join up. Even strangers approached men on the street and gave them a white feather symbolizing cowardice if they were not in uniform.

Statistics from Global Firepower.com

An average of over 60 men were killed for each day of the Great War. This had a profound impact on this neighbourhood where approximately every third house lost a man. The widows left behind were often hard pressed to feed their children and pay their rent or mortgage. Many had to sell their homes and move to smaller quarters, including to the tiny houses on Erie Terrace (now Craven Road). The desperately poor women of Erie Terrace sometimes lost their children to orphanages as they were unable to look after them on the meager widow’s pension. Young widows, women in their late teens and early twenties, moved into few apartment buildings in the Gerrard-Ashdale neighbourhood. By 1919, Morley Court, at the corner of Gerrard and Woodfield Road, was full of young war widows.

To many the sacrifice in the trenches was anything but glorious. The soldiers themselves became deeply cynical about the war propaganda. In 1914 they cheerfully marched off singing, Pack up your troubles in your old kit bag and smile, boy, smile but the grim We’re here because we’re here because we’re here because we’re here… expressed the stolid fatalism of many. Ironically, that sad, repetitive song is now a favourite at children’s summer camps; its origins are lost.

Ottawa stopped counting the deaths to due to old injuries, mental trauma and exposure to gas as war deaths in 1922. The Great War Veterans Association and later the Canadian Legion (formed in 1925) fought throughout the 1920s and onwards for recognition of these deaths and the injuries of survivors. Sunnybrook Hospital was founded to care for injured veterans. So many men were blinded, particularly by gas, that the men themselves founded the Canadian National Institute for the Blind, and obtained the right for blind people to ride free of charge on the Toronto Transportation Commission (TTC). When I was a child, it was not uncommon to see legless veterans of the Great War selling pencils on downtown Toronto streets to raise a few pennies to augment their pensions.

The Great War taught the men in the trenches to think for themselves and to trust only each other. There was a profound loss of faith in the elites of society, especially politicians. The First World War sounded the death knell for the Empires as returning veterans brought back to India, Africa and other countries definite ideas about democracy, a loss of faith in Crown and Country (especially since the Country was not their own) and a great grief at the loss of so many. Pre-existing independence movements were invigorated. The Empires of Europe had sowed dragon’s seeds that sprang up as armed men in generations to come.

This was the first true World War. Virtually no country was untouched. While the unravelling of the British Empire took some time, the writing was on the wall. The Raj was doomed.

In Toronto there was great bitterness, anger and resentment. In elections, men wanted “soldier candidates” saying “We only trust our own”. Often those candidates were the officers and sergeants who had led them into battle. When they came home to high unemployment with others in the jobs they considered theirs by right, violence broke out on the streets.

In the Great War, about 41% of Canada’s men of military age were in the armed forces. Statistics from Global Firepower.com

Statistics from Global Firepower.com

In the fall of 1918 the Great War in Europe was winding down and peace was on the horizon. Canadian troops were coming home. Deep within the trenches men had endured “hell without a lid”. Now veterans returned to reap the rewards of peace: jobs, families, children, homes, health and happiness. All too often, there were no jobs, just the dole. They lost their homes or had to take in lodgers.

The World War One veterans were politicized. They wanted their rights and they were not prepared to wait as they elected their own soldier candidates, often their sergeants, and formed potent lobby groups.

Nov. 27, 1918 The Toronto Star reported:

The churches of the middle-east district of the city held a torchlight procession and open-air thanksgiving service last night, proceeding to the old golf grounds at Small street, east of Coxwell avenue.

Among those who took part in the celebration were: Rev. Dr. Long, Rev. H. A. Berlis, Rev. (Capt.) Jones, Rev. S. A. Madill, Rev. J. Bushell, and Mayor Church. Controller Robbins put the first torch to the bonfire.

The procession was accompanied by bands of the Salvation Army and the Boys’ Naval Brigade. The churches represented were: St. Joseph’s, St. Clement’s, Riverdale Methodist, Hobbs Memorial, Rhodes Avenue Baptist, St. John’s, St. Monica’s, Rhodes Presbyterian, and the Salvation Army.

The War was over — finally. It hurt Toronto in many ways. Businesses were disrupted with skilled workers away at war, some killed and some seriously wounded. Business owners and entrepreneurs suffered the same fate. The work force shrank with so many men away. Businesses lost profits because of lack of demand for their products or because they were unable – as a result of a reduced work force – to meet the demand. Many families lost their primary bread winner and sank into poverty. Widows lost their houses. Some, desperate to keep their homes, broke them into flats or rooming houses. Some gave up their children, no longer able to care for them. Many children were orphaned, some raised by family, others disappearing into institutions. Many widows remarried quickly as it was virtually impossible for them to hold onto their home and family without a man, verifying an old saying, “That every woman is one man away from poverty.”

Newspaper Report Toronto Star, Oct. 11, 1918

1918 Dr. Hastings Forbids Conventions In City

Over 300 New “Flu” Cases are Reported at the City Hall.

List of the Deaths Increase Reported in the Schools – 50 Per Cent Absent From Some of Them

Dr. Hastings issued strict orders to-day that under no condition must conventions of any kind be held in Toronto until the present epidemic of influenza had died out.

There were forty new cases reported to the Department of Health this morning, while others will come in during the day. Up to date, 170 have been reported to the department. This, however, does not by any means represent the number of cases in the city, as there are over 300 cases in the hospitals alone….Up to noon to-day the following deaths from pneumonia and influenza had been reported since yesterday: … [Died of influenza] Walter J. H. Barber, 15 years, 206 Ashdale avenue. … Henry Hunter, 37 years, 589 Erie terrace. Martha Mitchell, 62 years, 4 Fairford street. …Rosie May Jones, age 37, of 19 Jones avenue. Agnes M. Ferguson, age 17, of 114 Logan avenue. Nellie McNelley, 201 Morley avenue…The epidemic of Spanish influenza in the Toronto schools is on the increase, according to information received by The Star this morning. In many of the larger schools as many as 50 per cent of the pupils are away, and in practically every school in the city, a large percentage is away sick.

Returning veterans were changed by the trenches. Angry at profiteers who had sold shoddy supplies and defective Ross rifles, they harbored a deep resentment of politicians, foreigners and those men, including Quebecers, who had not enlisted in high numbers compared to Ontario. Moreover, they came back in 1918 and 1919 only to face a recession and high unemployment.

: The blood of the men overseas was also on the large war-time profits going into the pockets of many Canadian manufacturers… Sixty thousand members of the L.O.L. had gone overseas with the Canadian army and 7,000 went from the City of Toronto alone.

Those of us who are now seniors are the last to remember the men and women who fought in the First World War. All of the veterans themselves have now passed away. Thomas Leo Doucette and his war bride, Lucy Agnes Devenish. Alfred Stevens, Royal Navy, aged 15 when this photograph was taken. (I am their grandchild.) The war diary of the First Canadian tunnelling division recording the award of the Distinguished Service Medal to Sapper James Doucette, brother of Thomas Leo Doucette, for gallantry in fighting in a mine under No-Man’s Land.

The Recessional below by Rudyard Kipling was often sung on Remembrance Day but is rarely heard now.

God of our fathers, known of old,

Lord of our far-flung battle-line,

Beneath whose awful Hand we hold

Dominion over palm and pine—

Lord God of Hosts, be with us yet,

Lest we forget—lest we forget!

If, drunk with sight of power, we looseWild tongues that have not Thee in awe,

Such boastings as the Gentiles use,

Or lesser breeds without the Law—

Lord God of Hosts, be with us yet,

Lest we forget—lest we forget!

For heathen heart that puts her trustIn reeking tube and iron shard,

All valiant dust that builds on dust,

And guarding, calls not Thee to guard,

For frantic boast and foolish word—

Thy mercy on Thy People, Lord!

James Laughlin Hughes, leading educator and prominent Orangeman, published a book of poetry, Rainbows on War Clouds, in 1919. His opinons about Roman Catholics had changed radically over the war. His only son, Chester Hughes, was killed in action on November 15, 1915, in Belgium. It’s not known when Hughes first began to form opinions which were the exact opposite of his earlier convictions, but the killing in action of Chester grieved him deeply. James L. Hughes was removed from the office of Grand Master because of his new ideas, but he persisted in going against popular Orange thought. “His views on the Orange war effort must have meant some lively lodge meetings.“ He had completely reversed his earlier stands on bilingualism and separate schools. He now went against the current Grand Master of Canada in 1918, H. C. Hocken, M.P., and openly supported bilingual schools. James Hughes never again had any real influence on Orange political policies. Canadianorangehistoricalsite.com

Toronto Star, Sept. 28, 1918. Ad for donations to Catholic Army Huts Campaign. Illustration from Toronto Star, Oct. 3, 1918. Army huts were recreational spaces where soldiers could relax, meet or participate in religious service such as the Roman Catholic Mass.