In 1866 one guidebook spoke of Toronto:

There is a total absence…of any beautiful scenery around the city.

(H. Beaumont Small, The Canadian Handbook & Tourist’s Guide. M. Longmoore & Co., 1866, 134) Most Victorian tourists looked for the picturesque – alps, not a flat, tilted plain by a wetland. They wanted to see grandeur – big rivers like the St. Lawrence not brooks.

Yet those small creeks were important.

It must be remembered in connection with the use of these rivers, and others even smaller, than the streams of today have much less water than they had in the days of the fur trade and early settlement. The clearing of the forests has led to the quick evaporation and drainage of the surface water, and many a noble river has shrunk to a mere creek, with insufficient depth to float a boat except in the season of spring floods.

(Edwin C. Guillet. Pioneer Travel. Toronto: The Ontario Publishing Co. Ltd., 1939, 7)

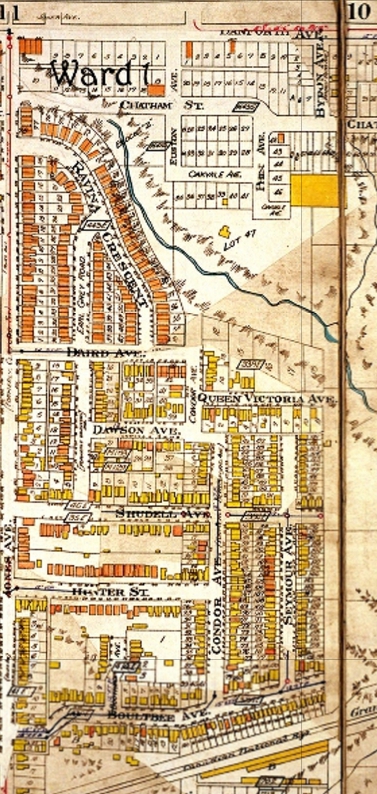

Hastings Creek began in springs just north of Danforth Avenue and flowed down between Jones and Greenwood Avenue to empty into Ashbridge’s Bay.

Detail, from Goad’s Atlas, 1903.

- One branch ran south across Danforth Road just west of Jones Avenue (the Pocket lies within the pink area on the 1903 map) and carved a ravine where Ravina Crescent is;

- Another branch crossed the Danforth just east of Jones;

- And another brook (not shown on most maps) crossed Jones Avenue itself to join Hastings Creek.

Mr. Stephens showed me a small stream runing through his farm, which I could easily jump over. He told me that one afternoon he was watering his horses, when he perceived a shoal of salmon swimming up the creek. He had no spear at home, having lent it to a neighbour. He, however, succeeded with a pitchfork in capturing fifty-six fine fish.

(Samuel Strickland, 75-77)

Hastings Creek exposed clay beds along its routes and brickmakers exploited these in some of the largest brickyards in Canada in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

Directly west of 456 Jones was a ravine, carved by this little tributary to Hastings Creek.

Crossing the Danforth

At Jones and Danforth was an eight foot wide stream with a wooden bridge over it.

(Interview with Harry Clark, c. 1977 in Local History Collection, Broadview & Gerrard Branch, Toronto Public Library)

…to cross the Danforth at Jones one had to go down a set of stairs, cross the road, then climb four more steps on the other side.…further down, on Jones, there was a bridge that crossed a creek which started at Langton, went underground in the direction of Ravina.

(Interview with Mrs. Cooper, 456 Jones Ave c. 1997 in Local History Collection, Broadview & Gerrard Branch, Toronto Public Library)

Brickmaking and How It Changed The Neigbhourhood

From 1830 to 1840 (and earlier) brick making was by hand, using the “slop-mud” method. A home industry supplemented their brick yard profits with farming, tavern-keeping or ice-cutting in the winter. Some small yards operated along Jones Avenue near Hunter Street. Brick making was virtually unchanged from the 1700s, but by the end of the nineteenth century, change swept through the brickyards. (Robert J. Montgomery, “The Ceramic Industry of Ontario” in Thirty-Ninth Annual Report of the Ontario Department of Mines. Vol. XXIV, Part IV, 1930, 4)

By 1900 the brick industry was changing, industrialized and was no longer craft, family-oriented, small scale. Brick clay was running out and brick manufacturers turned to a soft sedimentary rock, shale, to make “shale brick”. By 1905 four brickyards lay north of the rail line on Greenwood Avenue. They extracted blue clay and shale from deep quarries here by blasting with dynamite. It was dangerous and noisy and the neighbours in the Pocket hated it. A steam shovel set on a railroad car on a portable narrow-gauge rail line hauled the broken rock up from the deep quarries to the brick plants at surface level along Greenwood Avenue. The shovel and the locomotive were called “a Dinky”; the cars were “Dinky cars”.

The number of brick manufacturers on Greenwood quickly multiplied and the shale pits grew wider and deeper. By World War One the pit on the west side of Greenwood stretched almost to Danforth Avenue as did the quarry on the east side of the road. Each pit had more than one brick manufacturer working in it, each owning a piece of the valuable property in the hole. Originally each brick manufacturer dug their own hole but soon the holes merged together.

Ken Smith remembered in an interview in the Toronto Public Library’s local history collection:

On both sides of Greenwood were brickyards, and we used to play there weekends. The west one is now T.T.C. yards, and the eastern section is now a subdivision of houses. I have sometimes wondered whether the eastern one (which is built on landfill), since it was a deep hole, extending nearly over to the fence at Monarch Park, would find any of the houses sinking. They had a narrow rail line going down into the hole, where they let down a small dump car [dinky] to haul up the clay for their bricks.

(Ken Smith. The East End: Personal Recollections of Toronto, East of the Don River from 1915. Toronto: The East End Seniors’ Educational Volunteer Organization, n.d. Brochure, 8.)

Just as the good blue brick clay was being used up, houses built of the very same brick spread over the East End, making remaining clay deposits inaccessible. Only shale was left and the shale pits, hemmed in by housing, could not expand. They could go down deeper. Once a property had been subjected to the digging, blasting, scraping and general mayhem of brickmaking it was pockmarked, denuded vegetation, with a hard clay surface. In a delightful nineteenth term, it was “as bald as a brickyard” (Toronto Star, August 4, 1911) Ugly gaping holes were left in the landscape but neighbours welcomed the closing of the brick yards. The constant smog and noise of the brickyards made life difficult and brought down property values.

But it got much worse for the neighbourhood. Albert H. Wagstaff was a very successful brick manufacturer and would-be politician who diversified into building houses and apartments, manufacturing trucks and other ventures. When he died in 1931 he left his extensive brickyard to his drinking budy, Albert Harper. After the arguing over Wagstaff’s will was settled in court, Harper turned the brickyard into a garbage dump. With the huge dump, property values fell and many people left for less smelly pastures and poorer people moved in.

THE ONCE AND FUTURE POCKET

The Pocket lies between Danforth Avenue on the north, the Greenwood TTC yard on the east, Jones Avenue on the west, and the CNR train tracks on the south. The Pocket was originally developed as a subdivision called Eastmount, but that name has been lost in time.

Toronto grew by almost 700 % from 1851 to 1901. The 1880s and 1890s were decades of great population growth “over the Don” also nicknamed “The Goose Flats”. Reliable, efficient and inexpensive public transit, in the form of the streetcar, was the key to suburban living.

People complained: “The residents in the north-eastern section are displeased atnot having a street car service either along to Jones Avenue on Gerrard street or up Pape Avenue to Danforth from the present terminus on Gerrard Street.” (Toronto Star, November 20, 1894)

Letter to The Editor

The Street Car service in the East End is a disgrace to the city, and most discreditable to the Street Railway, and the aldermen in Ward One should have some regard for their constituents and make this fact known to the authorities, for they know it themselves. The people over the Don are supposed to have an eight-minute service, and the people east of the Woodbine get only half as good a service. A man who misses the car often has time to walk up town before another one overtakes him.

EAST ENDER

(Toronto Star, January 29, 1895)

Toronto Public Library, 1900

A 1903 Letter to the Editor from Resident complained:

…the lack of street-car accommodation stands as a barrier to its more rapid development in the district bounded by Broadview Avenue, Danforth road, Greenwood Avenue and Gerrard street. Prospective builders … are waiting for an indication of car extension in this locality. Property has changed hands to quite an extent recently. A general increased value is apparent, and all that is necessary to a rapid growth in this locality is an extension of the Broadview line east along the Danforth road and down Pape Avenue to the Gerrard street line, or east on the Danforth road to Jones Avenue, thence south to Queen street.” …”Distance makes it imperative to take c car, and popular following would soon tend to increased traffic of the female portion of the home.

(Globe, May 21, 1903)

In 1903 The York County Council considered the state of the roads and whether they should be improved. “Councillor Baird stated that he was very much opposed to paying out money for good roads and then have “the automobile fellow” come out on them from Toronto. He stated that these machines went at a terrific rate, and were very dangerous.” (Toronto Star, November 27, 1903)

1903 Letter to Editor from G. Vennell

It is a mistake to suppose that all this land is used as market gardens, brick yards and cattle ranches. There are hundreds of acres of some of the best residential sites in the city unoccupied, and only waiting street-car facilities to be taken up and built upon. As it is, houses are going up in every direction. There are a number of streets well laid out, with water and gas mains, and school and church accommodation equal to any portion of this city.

(Globe, June 13, 1903)

In 1906 the city began building the street car lines along Danforth Avenue. To build the street car lines, two gangs of approximately 50 men each dug up the roadway. A substructure was then laid and the roadbed paved. A lot of grading was required and a steam shovel was used. Gerrard Street was extended east Greenwood Avenue. An 18-foot allowance was for the car tracks and the roadway was 54 feet wide.

In 1912 the City began building the street car lines along Danforth Avenue. To build the street car lines, two gangs of approximately 50 men each dug up the roadway. A substructure was then laid and the roadbed paved. They laid double tracks from Broadview to Greenwood. A lot of grading was required and a steam shovel was used. Gerrard Street was extended east Greenwood Avenue. An 18 foot allowance was for the car tracks and the roadway was 54 feet wide. In December, 1912, street cars began operating along Gerrard Street east of Pape. Mayor Hocken and City Controllers inaugurated the new Civic Streetcar line on Gerrard Street East, December 16. The Mayor, Controllers, Alderman and city officials were in the first car. Ordinary citizens were in the others, free of charge for just that day. “No smoking will be allowed on the cars any day.” (Globe, Dec. 14, 1912)

And then people could see that this part of the east-end was being brought very, very near to downtown, and that it was a beautifully wooded stretch of land. The cars discovered Gerrard street. They have taken hundreds of home-site buyers and builders down there.

(Toronto Sunday World, December 22, 1912)

Development followed creating “streetcar suburbs” of very similar houses.

A typical 1912 house had six-room bungalow: living room, dining room, and kitchen, downstairs; and three bedrooms upstairs:

$2,400 – Last one of 6 comfortable homes, East End, brick front, 6 rooms and bathroom, beautifully decorated, concrete cellar and Pease furnace, verandah, $200 down, balance equal to rent; don’t miss this please.

(Toronto Star, April 23, 1909)

In 1909 Gustav Stickley published the first catalogue of Craftsman homes, complete with floor plans, popularizing the bungalow and the Arts and Crafts style. At this time, not only could a young couple buy a pre-fabricated house or build their own, they could also buy a complete suite of furniture to fill the house:

Real estate agents began subividing the east side of Jones Avenue south of the Danforth in 1911, promoting it to speculators hoping to buy up lots cheap and sell them later for a profit. Ravinia Crescent was completely built up by 1912.

An Immigrant Story

The Richardson family landed in Quebec, Canada on the SS Bavarian on 5 or 4 August 1904, (the SS Bavarian landed at Quebec on 4 August 1904). By 1910 they were residing at 17 Dorean Avenue, Toronto. In 1910 Arthur traveled to Fort Worth, Texas and he wrote on 12 January 1964 “I went there in 1910. ….. at that time it was a wild place then I worked on a large Building in Fort Worth it is an inland Country there is no ocean or sea beaches, around Fort Worth so I took a Trip to Dallas there was ocean around there. But I did not stay there long I had a family of five Children”. At the start of World War One they left Canada. Arthur said that he tried to volunteer for the war effort in Canada but was not accepted as he was married. In 1913 when daughter Ivy was born, they were living at 7 Baird Avenue, Toronto in a two story house that Art had built. When they first arrived in Canada they had been living in a tar paper shack. On 28 May 1915 the family immigrated to the United States through Niagara Falls, New York with cash assets of $1077.00, which was a tidy sum in those days. (Aunt Ivy says they came through the Port of Huron at Sault Saint Marie.) The money was probably from the sale of the house on Baird Avenue, as Ivy said they sold it just before leaving Canada. (Soundex Index to Canadian Border Entries 1895-1924, Roll 323 Manifests of Passengers Arriving in St. Albans, VT Dist. 1895-1954, Roll 284, National Archives, Washington; remembrances of Arthur James Richardson, Edward J. Richardson, Lillian Via Richardson and Florence Richardson Heming). for more info http://members.cox.net/barneykin/rich/RICn03.htm

Restrictions in the Mceachren & Sons ad refers to the brick limits. The City of Toronto had passed bylaws to prevent diastrous fires. These had devastated a mostly wooden city from time to time in the nineteenth century. The bylaws set boundaries within which all new buildings had to made of brick. These were the brick limits and buildings within them were restricted to bricks only. The location was high but it was no “Rosedale of the East” being situated next to large brickyards with constant smoke and, even more, disconcerting, constant blasting with dynamite.

McEachern did provide us with something rare: a before and after photograph.

The Toronto World has a much clearer picture. We are loking east towards the brickyards behind the orchard.

September 26, 1913

Eastmount Park was developed just as World War One broke out and the streets there had their share of heartache and hope.

While the war in Europe was going, Toronto was booming as people migrated to the city to work in munitions plants. The East End had a number of munitions plants as well as many factories along Carlaw and Eastern Avenue, as well as Dunlop Rubber on Queen Street at Booth Avenue.

Roy Vincent Harman was on Jones Avenue and was a sheet metal worker when he joined the army on February 25, 1916. His wife, Mary Sophia Gardiner, known as “May” and their four-year old daughter, moved to 95 Ravinia Crescent after he went overseas. He went missing during an an attack near Cherisy on the morning of August 30, 1918. His body was found two weeks later and he is buried in the Quebec Cemetery, Cherisy, Departement du Pas-de-Calais, France.

Many men from Eastmount Park served and a number never came home. Londoner Alfred James Cook returned to 81 Ravinia Crescent and his wife, Jennie Elizabeth. He was older than more men when he joined up in 1915, but was a veteran, having already served 20 years in the British Army. He immigrated to Canada in 1894. Like many of the volunteers, he was married with children.

The neighbourhood was beginning to fill with neat brick houses although prices rose significantly as there was a post-war housing shortage in Toronto.

The City of Toronto was already beginning to dump garbage into parts of the brick pit where quarrying had finished. Neighbours on Shudell, Hunter, Baird and other streets complained of the smell, flies and rats attracted by the trash. The dump would only get bigger.

In 1923 John Cook of 166 Concord Ave objected to his assessment claiming that the smoke and smell of the brickyards drove down the value of his property. Ida May Lennox of 80 Shudell Avenue also objected to her tax assessment on the same grounds. Alex Ewing, 42 Hunter Street; E. F. Whynot, 40 Hunter Street; Charles H. Burk, 38 Hunter Street, and Thomas Smith, 36 Hunter Street also asked for lower taxes. They argued that the smoke from the brickyards and the poor condition of their street entitled them to pay less. The noise and smoke from the rail line was also detrimental. Other home owners on Frizzell complained about the nearby brickyards.

Despite the difficult environment people lived in, there doesn’t seem to have been much crime in the Pocket of the 1920s, certainly very little compared to some streets such as Rhodes or Craven Road. Those in the Pocket were more likely, it seems, to be victims of crime, usually break-ins or muggings than perpetrators. But neighbours then, as now, looked out for neighbours.

Globe, Nov. 28, 1923

People then, as now, were not happy with the TTC service.

A new high school was built to serve the neighbourhood. The Pocket was full of white collar workers as well as lots of blue collar workers too. The high school trained those who were going into business.

Eastern Commercial School

Photo between 1926 and 1946

Eastern Commercial School, now Eastern Commerece. Photo in the 1930s.

The brick pit was causing more problems as children got into through breaks in the fence and the sides of the cliff eroded.

The area had many people who spoke up for their rights, including the right to margarine.

1963 Public Domain, National Archives, USA

James Earl Ray

The area was rough and tough in the old days. Some joke that it was the “Least End” not “the East End.”

6 Condor Avenue was a brothel where James Earl Ray is reputed to have hid out in Toronto after assassinating Martin Luther King (April 4, 1968). But some say was never here, including the assassin himself. Instead, Ray claimed that he stayed in rooming houses on Ossington Avenue. and Dundas Street West for nearly a month.

In 1993 journalists from the Ottawa Sun, and Robert Benzie interviewed Ray at Nashville’s Riverbend Maximum Security Institution to mark the 25th anniversary of King’s death. One day, Ray told the journalists, he was stopped by a police officer. “He said I was jaywalking and asked for my name and address,” Ray said. “I’d got an address from a lonely hearts club … to use as a cover. So I gave him this address from … Condor Avenue. I’d never contacted this woman or anything, but I guessed the police wouldn’t check it.”

However, reputable local people insist that he was there, in the house and he was just trying to cover for the woman so she would not face arrest as an accomplice. Ray was a seasoned professional criminal who was a practice liar. He used multiple identities to escape capture. On May 6, 1968, Ray boarded a flight to London. What was then considered the biggest manhunt in history ended on June 8, 1968, when officers arrested him at Heathrow Airport.

James Earl Ray insisted he was not a run-of-the-mill assassin and different from Sirhan Sirhan who killed Robert Kennedy and Lee Harvey Oswald who shot John F. Kennedy:

“I don’t think I have much in common with these others,” Ray told me. “I mean, Sirhan, he’s Arab from Jordan or wherever and Oswald, he was in politics. Here I am, I’m just involved in criminal activity. I just did dumb things like coming back to the United States from Canada.”

(Robert Benzie, “How Toronto concealed King’s killer”, Toronto Star, April 05, 2008)

The Pocket has always been home to big personalities.

To remember these big-hearted adventurers, the friends and family set up a registered charity the Seltzer-Chan Pond Inlet Foundation.

- The Seltzer-Chan Pond Inlet Foundation aims to help the community of Pond Inlet by:

- helping to preserve Inuit traditions, culture and language

- assisting Inuit students with education or training programs

- relieving poverty

For more information about the Seltzer-Chan Pond Inlet Foundation go to http://pondinletfoundation.org/aboutscpif.html

Susan McMurray, co-founder and co-editor of The Pocket newsletter, and her neighbours made up the name, the Pocket. . They launched the newsletter in 2003. In the 1990s young urban professionals, nicknamed “Yuppies” somewhat unkindly, began buying houses in the Pocket. Many were rundown and were often completely gutted and recreated from top to bottom. At that time, many decorated their walls austerely with white paint so they were also called “white painters”. An older resident recalled, “a ravine that cut through the area before it was turned into a landfill, then covered with buildings and greenery”. Ravina Crescent, a winding street south of Danforth Ave. follows the route of that branch of Hastings Creek, which in the Pocket is known as “Ravina Creek.”

Susan McMurray, co-founder and co-editor of The Pocket newsletter, and her neighbours made up the name, the Pocket. . They launched the newsletter in 2003. In the 1990s young urban professionals, nicknamed “Yuppies” somewhat unkindly, began buying houses in the Pocket. Many were rundown and were often completely gutted and recreated from top to bottom. At that time, many decorated their walls austerely with white paint so they were also called “white painters”. An older resident recalled, “a ravine that cut through the area before it was turned into a landfill, then covered with buildings and greenery”. Ravina Crescent, a winding street south of Danforth Ave. follows the route of that branch of Hastings Creek, which in the Pocket is known as “Ravina Creek.”

In 2006 some 3,000 people, most between the ages of 15 and 65, according to a Statistics Canada report commissioned by the newsletter. More than a third were first-generation immigrants, and nearly 40 per cent identified themselves as visible minorities. Pocket residents work hard at improving their neighbourhood with events such as annual litter-pickups, tree-planting drives and a volunteer-built ice rink in the park. (Toronto Star, March 14, 2009)

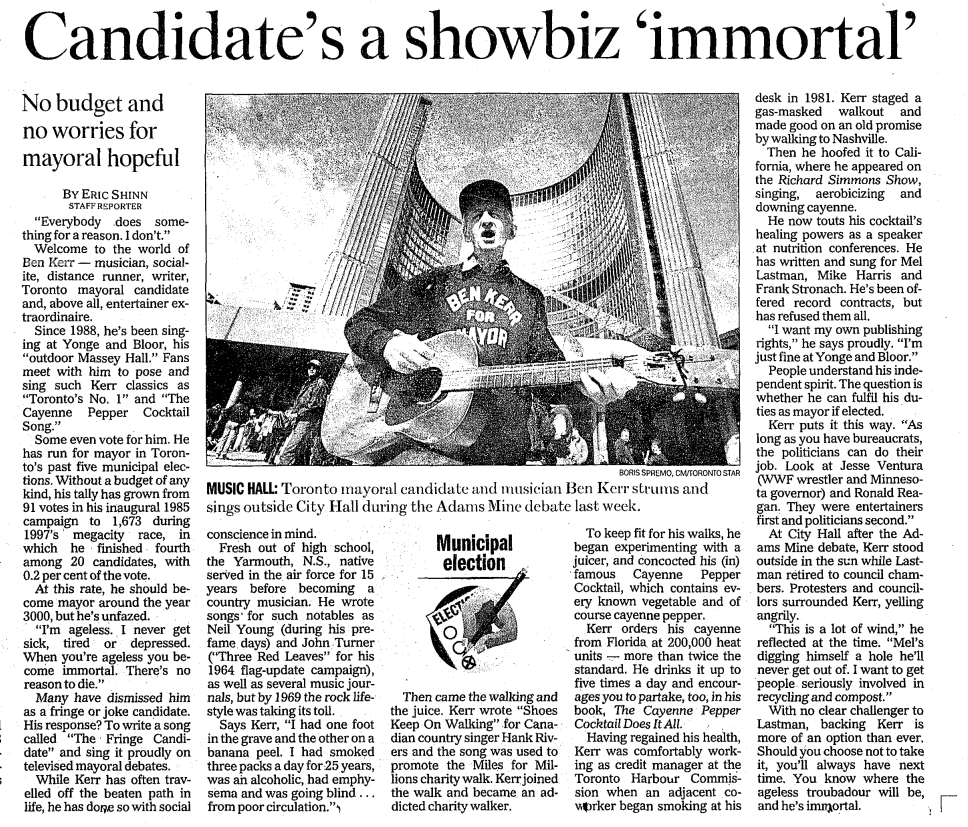

Ben Kerr

Ben Kerr, a busker and perpetual mayoral candidate, was probably the most famous Pocket resident. Ben Kerr Lane is named for him.

The Ravina Project: 75 Ravina Crescent

Gordon Fraser and Susan Laffier created the Ravina Project to transform their 1925 brick house into a state-of-the-art, energy efficient home. Their goal was also to educate others about energy conservation.

They insulated and upgraded their windows to reduce heat loss. Replacing their oil furnace and electric hot heater with an on-demand, 95 percent efficient, computer controlled boiler significantly cut heating costs. They installed a solar array on part of the roof. An interlocking tetrahedral structure designed by Ben Rodgers of the North American Board of Certified Energy Practitioners (NABCEP) supports the array. Their basement houses big batteries that can hold up to 14 kilowatt hours of power. This is more than enough for their house. Left over energy feeds back into Toronto Hydro’s power grid so that their hydro meter then runs backwards. The house has electrical panels that allow them to go off-grid if necessary. They also a wind turbine that runs quietly and is unobtrusive. (Dave LeBlanc, Globe and Mail, Oct. 12, 2007) See http://www.theravinaproject.org

This is not the only environmental initiative to come out of the Pocket.

The Railroad through the East End

But now we will step back in time as we discuss the railroad. From 1846 to 1849 Irish navvies built Ontario’s first railroad, the Ontario, Simcoe and Huron Union Railroad. 1847 about 105,000 Irish emigrants left for British North America, many landing at the Simcoe Street docks.

Larrat Smith lamented:

They arrive here to the extent of about 300 to 600 by any steamer. The sick are immediately sent to the hospital which has been given up to them entirely and the healthy are fed and allowed to occupy the Immigrant Sheds for 24 hours; at the expiration of this time, they are obliged to keep moving, their rations are stopped and if they are found begging are imprisoned at once. Means of conveyance are provided by the Corporation to take them off sat once to the country, and they are accordingly carried off “willy nilly” some 16 or 20 miles, North, South, East and West and quickly put down, leaving the country to support them by giving them employment….It is a great pity we have not some railroads going on, if only to give employment to these thousands of destitute Irish swarming among us. The hospitals contain over 600 and besides the sick and convalescent, we have hundreds of widows and orphans to provide for.

(Larrat Smith in Careless, 71)

In 1852 the Canadian Government announced plans to build a railway from Montreal to Toronto. The Grand Trunk (GTR) formally and won the charter to build a railway through Canada East and Canada West. Navvies built the line as quickly as possible. In 1856 the Grand Trunk Railway advertised that it was opened “Throughout to Toronto on Monday October 27”. The chief freight was grain, tan-bark, timber and cordwood — most of it still the produce of the forest. Irish backs and Irish brawn built the railroads of Ontario. The GTR ran through and local trains.

GRAND TRUNK RAILWAY

NEW SUBURBAN TRAIN SERVICE

….Suburban trains are run between York and Weston, calling at Greenwood’s Ave, Kingston road, Don, Berkeley street, Church street, Yonge street, Union station, Queen’s wharf…

(Globe, May 6, 1887)

The Grand Trunk Railway (GTR) trains stopped at the level crossing Kingston Road (now Queen Street), on the south side of the road, east of the tracks. The crossings through Leslieville were only protected by a sign. Rail crossings were simple flat and dangerous.

In 1883 the GTR double tracked its line across Toronto and, as the brick industry grew, the number of sidings grew with it. In 1884 the GTR built an iron railway bridge was built over the Don south of Queen. The GTR opened a large freight assorting yard south of the Danforth and west of Dawes Road. The next year the railway opened a roundhouse and the York Station. As a result, the nearby hamlet of Coleman’s Corners grew into the village of Little York.

In 1889 a streetcar line opened on Broadview Avenue to take local residents south to downtown. This brought more growth to the area and some properties near Doncaster and Todmorden were subdivided. By 1889 Gerrard Street (formerly Rembler’s or Rambler’s Road) had been extended to Greenwood’s Lane. In 1895 the Grand Trunk Railway began stopping the local trains to pick up passengers at Queen Street East, “at the old Kingston road crossing hear Leslieville”. This was in addition to the suburban trains that already stopped there. A railway station was planned. It was not long before there were complaints about “the lack of shelter of some kind at the crossing of Queen street at the Don. In wet weather passengers become drenched wile waiting for the train if they are ahead of time or the train is behind, and in the cold weather people are half perished, there being no shelter of any kind.”[1] (Toronto Star, April 13, 1895)

In 1900 the GTR built a new station north of Queen Street on DiGrassi Street. Sadly it was demolished in the 1970s). Traffic along the GTR lines grew and grew. However, despite this, in 1918 the GTR was in financial trouble. It was nationalized as the Canadian National Railway.

From 1921 – 1923 William W. Hiltz was city controller, later Mayor. He was instrumental in getting the new Union Station built, along with the Toronto Viaduct, long-promised by the Federal Government. Construction began June 17, 1925 on the Toronto Grade Separation project (a.k.a. Viaduct). It was completed on January 31, 1930 that it was completed. The Viaduct extends between John, York, Bay, Yonge, Jarvis, Parliament, Sherbourne and Cherry Streets a distance of over 2 miles with approaches reaching farther beyond at both ends. For more info go to http://www.trainweb.org

As we leave the Pocket and go through the underpass on Jones Avenue we turn east and here the creek is known as “Hastings Creek” today.

Here is a slide show of Jones Avenue. All photos were taken in 1952 and are from the City of Toronto Archives.