George Leslie was not the only Leslie in Leslieville: other of Clan Leslie lived on McGee Street and built it. McGee was originally called Darcy Street and was laid out in the mid 1860s and named after D’Arcy Boulton, a rich member of the Family Compact. (Bolton Avenue) is also named for him. In 1877, to prevent confusion with another Darcy Avenue, the street was renamed McGee likely not after D’Arcy McGee (1825-1868) but the McGee family of grocers who lived at the corner of McGee and Queen.

This Father of Confederation was assassinated on April 7, 1868 by an Irish nationalist. So the street was named after a murder victim, but crime on McGee did not stop there. Robert Leslie had a business at Strange Street and Queen Street. And I will try to tell some very strange stories about this family of Leslies and others who lives (and died) on this short, but interesting, street.

The other Leslie of Leslieville

The other Leslie of Leslieville, Robert Leslie (1812-1886) came to Toronto with his brother George in 1826. He became a carpenter and worked as a builder in Streetsville where George and Robert’s mother and stepfather settled in the 1820s.

Robert stayed in Toronto until 1836, when he moved to New York City. He married Mary Ann House in New York City on March 22, 1837. (New York Evening Post, March 24, 1837) He remained in New York. Robert Leslie and Mary Ann House had twelve children: John Robert Leslie (1838–1899), James Edward Leslie (1841–1930), Philomela Margaret Leslie (1843–1917, George Henry Leslie (1846–1926), William Leslie (1847–1878), Frances Anna Leslie (1850–1914), Charles Leslie (1854–?), Alexander Chalmers Leslie (1854–1910), Norman Robert Leslie (1855–1939), Joseph Leslie (1859–?), Josephine (Josie) Montrose Leslie (1860–after 1938), and Emma Leslie (1862–1947).

In 1840 Robert and Mary Ann Leslie returned to Canada, going back to Streetsville, Peel County, where he became well known as a contractor and builder. Charles Dingwall and Robert Leslie had a business together as builders in Streetsville. But by 1865 the skilled and respected builders had overextended themselves and were in deep financial trouble. Their creditors called a meeting at the Telegraph Hotel in Streetsville on March 9, 1865. At the meeting Robert Leslie and Charles Caldwell presented their financial statements and an Assignee was appointed. (Globe, March 7, 1865) The well known builders and partners were bankrupt. Their machinery was sold at public auction on October 10, 1865, at their place of business in Streetsville. The machinery included:

1 Steam Engine, 10 horse-power, Planing, Sash, Mortice [illegible], Boring and other Machines, all in good working order, a large quantity of Bolting and Shafting, and a variety of other articles belonging to the above estate. (Globe, Oct. 9, 1865)

Robert Leslie “retired” immediately, moved to Toronto and after several years came to Leslieville where he worked as a builder and contractor. In his later years, he became a cabinet and furniture maker with a store at the south east corner of Strange Street and Queen Street.

It has always puzzled me why people don’t consider McGee Street in Leslieville because Robert Leslie family of six sons and six daughters living at 26 McGee Street (now demolished) must have stood out even at a time of large families. But Robert Leslie no doubt got a very sweet deal for his lot on McGee from brother George. It was no accident how Robert Leslie landed on McGee Street. His brother, George, owned the street!

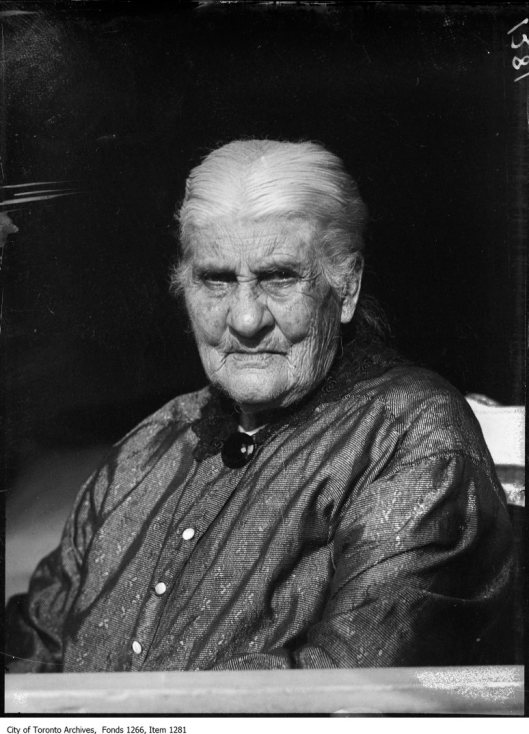

Courtesy of Leslie Sparks

George Leslie was a successful market gardener and tree nurseryman, but was also an astute investor, buying and selling real estate and amassing a fortune. George Leslie cut out the middlemen by being his own developer, subdividing land, building and selling the lots themselves. The land made him rich, not just trees. In the 1840s and 1850s he bought up significant blocks of land for little money, but later sold them for much more as the area developed. 1850s subdivisions in Leslieville included:

- a) from Kingston Road down to the lake on both sides of McGee and west from there to the GTR and Saulter Street;

- b) and east of what is now Winnifred to Caroline south from Kingston Road to the lake;

- c) land west of Curzon over to the western boundary of what is now Lesliegrove Park (including large buildings and what appears to be a greenhouse in what is now Lesliegrove Park);

- d) building lots on both sides of Curzon near Kingston Road, and along the north side of Kingston Road from Leslie to Curzon;

- e) the Post Office at the north west corner of Curzon and Kingston Road; and

- f) a large parcel of land on the north shore of Ashbridge’s Bay stretching westward from the foot of Leslie to what is now the foot of Pape.

His Toronto Nurseries occupies a large block of land from Caroline Avenue stretching eastward to Leslie and from Kingston Road on the north to Eastern Avenue on the south. Land speculators, like George Leslie, planned the first subdivisions including the first real subdivision in Leslieville. It was north of Kingston Road between Leslie and Curzon around the Roman Catholic Church and School. George Leslie was a singularly open-minded man who had no problems with selling to Irish Catholics. (The Protestant foreman of Leslie’s Nurseries married a Catholic and wasn’t fired or reprimanded in any way). The second subdivision, dominated by Protestants, was south of Kingston Road, between Leslie and Lake (Knox Avenue). The third was George Leslie’s second venture as a developer. He bought a triangular piece of land at the west end of Leslieville near Eastern and McGee and laid out streets and plots.

In the mid-1850s many would-be developers and land speculators planned housing subdivisions, in areas at the edge of town and even too far from town for immediate urban development. Subdivision plans combined large lots for country estates, market gardens, or later speculation with small urban lots located along the major roads. However at first Leslie’s subdivision lots on McGee did not sell. Sometimes subdivisions were too far from town and failed. Sometimes the location was poorly thought out and unattractive except to very poor people. The subdivision at the GTR and McGee did not have many houses until thirty years later when it filled with labourers. At that time there was no standard size or arrangements of lots, and no municipal planning, and developers only had to register their plans with municipalities like the City of Toronto or County of York. This allowed rendering plants, like William Harris’s on Pape’s Lane, to co-exist closely with churches and homes. The lots on McGee were uncomfortably close to George Gooderham’s cow barns with their stench, the train tracks and the marsh with its mosquitoes. For more info about the early days of Leslieville borrow my book “Pigs, Flowers and Bricks: A History of Leslieville”, from the public library or go to:

McGee Street was not a very desirable location. The street was in terrible shape, but for years Queen Street wasn’t much better.

The Kingston-road, or Queen-street east, is literally a river of mud. Since annexation to the city nothing has been done to put or keep the road in repair. It was torn up last winter for the construction of the sewer, and it has remained just as the contractors left it until the recent rains, which have broken it all up. The road is full of holes, which cannot be seen in consequence of their being filled with mud. The tramway is, if possible, in a worse condition than the rest of the road. While it keeps the water from running off on the south side…the space between the rails is over ankle deep, with water thickened with clay, and the car horses splash this mixture on the fronts of the stores at the roadside, and any goods that many be exposed for sale….The other streets leading north and south, except McGee-street, which has recently been block-paved, show similar signs of neglect, so that the whole neighbourhood is in a pretty pickle. Even on McGee-street the sidewalk has not been replaced… It is not safe to life and limb to travel these roads. (Globe, Nov. 10 1885)

Robert would have benefited from George’s generosity as well as his connections and influence as the biggest employer in the neighbourhood and Justice of the Peace. However, the relationship was mutually beneficial as Robert no doubt built George’s house at Jones and Queen (now sadly demolished) as well as the Leslie General Store and Post Office at Curzon and Queen (still standing and now a restaurant.) and the original Queen Street East Presbyterian (since rebuilt several times). (Globe, March 24, 1883)

In 1871 The City of Toronto extended South Park Street (now Eastern Avenue) east from Mill Street (Broadview Avenue) to D’Arcy Street (McGee Street) and opened D’Arcy Street from the Kingston Road (Queen Street East) to Front Street East. Within 30 years, Eastern Avenue would become one of the two great industrial streets of Leslieville; the other would be Carlaw Avenue.

George Leslie, for whom Leslieville is named, was instrumental in planting the first street trees in Toronto. According to the Globe, “Mr. Leslie did much to open up and develop the east end, planting many trees that now afford grateful shade to pedestrians.” (Globe, June 26, 1893)

He also donated the land for Eastern Avenue through Leslieville and lined it with one his favourite trees, horse chestnuts, as he did Kingston Road (now Queen Street East).

Desirous of making improvements in the east end of the city, Mr. Leslie proposed the opening up of a new street through his own lands, south of Queen street, and to his energy and liberality are largely due the creation of what was at first called South Park street, now Eastern avenue, he donating the right of way through his own grounds, a length of some 2,000 feet, equal to several acres. Under his supervision, and entirely at his own expense, this avenue was planted, as were other streets in the neighborhood, the rows of horse chestnut in front of the Queen street property being considered the finest in the Dominion. (Globe, May 6, 1893)

Squire George Leslie was also generous with his land, or perhaps, he simply wanted fire protection as some of his buildings had been destroyed in a fire. In 1883 George Leslie gave 50 feet of ground to build a fire hall at the corner of McGee Street and Kingston Road. He also donated “enough shade trees to plant along the front.” (Globe, March 24, 1883)

In the 1880s housing began to fill in the market gardens and brickyards along Queen Street. Ads enticed:

Buy a home for yourself at the immense sale of lots on Queen’s birthday on the grounds, Carlaw-Avenue, Kingston-Road. Geo. D. Morse & Co. (Globe,, May 19, 1881)

Leslie successfully sold some of his lots:

East End Lots, Remember the Great Sale of City Lots on Saturday Afternoon at 3 o’clock, on the grounds, part of Leslie’s Nursery, Kingston-Road. Gas and Water Supplied. Low assessment. Terms Easy. Apply for particulars to Morrison, Taylor, & Co. 77 Front-street East. (Globe, June 8, 1883)

An 1884 advertisement made clear who the target market was:

CHEAP BUILDING LOTS. We are selling Cheap Building Lots on Carlaw-avenue, Eastern-avenue, Morse-st., Blong-st., and Kingston-road on very easy terms of payment. NOW IS THE TIME FOR WORKING MEN TO SECURE A HOME. POSTLETHWAITE & GRAHAM, 34 King-st., East. (Globe, August 2, 1884)

Cheap houses filled in George Leslie’s unsuccessful subdivision on McGee. Like a lot of working class homes of the time most of these houses were rough-cast, just plaster over lathing. A typical ad for the neighbourhood offered “two rough-cast semi-detached cottages containing four rooms” that rented for $4 a month each. (Globe, January 31, 1883)

Today a single developer usually handles the whole process of developing a subdivision from buying agricultural land, laying it out in streets, assigning lots, building houses and selling them. But, back then, land owners usually sold their property to a land agent. The agent divided it into lots and sold five of the lots to this person, four to that, etc. Then the person with five lots put up houses himself or paid someone else, usually a local builder, such as Robert Leslie to build them. So it is quite likely that Robert Leslie and his sons built most of the housing along McGee and neighbouring streets.

Robert Leslie was a master builder, who built many smaller homes and buildings still standing on Leslieville’s streets, but his surviving masterpieces are in Peel Region. In 1857 Robert Leslie, Charles Caldwell and Robert Heron Leslie built the majestic Benares House for the Harris family in Clarkson. The house was donated to the Ontario heritage Foundation in 1968 and restored. It is owned and operated by the City of Mississauga.

The William Barber House is also attributed to Robert Leslie. The City of Mississauga designated this amazing Italianate house under the Ontario Heritage Act in 1982.

The Hammond House in Erindale was finished in 1866 but so was Robert Leslie’s building career in the area.

Market gardens, brickmaking and raising and slaughtering cattle and pigs were the pig industries in Leslieville making the largely Scottish and Scottish-Irish business class wealthy. The area on the south side of Queen Street, between George Leslie’s holdings at McGee and Logan Avenue, was completely devoted to cattle raising. The biggest families in this business were the Blongs who owned land from what was then called Blong Street [Logan] and Queen to Empire and the Clarkes west of what will be Empire. (Charles E. Goad, Goad’s Atlas, 1884, Plate 35) Therefore, the south side of Queen Street to Eastern Avenue, dominated by pasture land and orchards, is the only section of Leslieville not dug up for brickyards. (Globe, May 15, 1883)

Robert Leslie opened a furniture factory and retail business called Leslie & Co. at the corner of Strange Street and Kingston Road (now Queen Street East). When interviewed later in life, he said he had six sons and four daughters (all alive but one), but actually had another daughter Josephine or Josie that the family had disowned after she engaged in a scandalous love affair. (G. Mercer Adam, History of Toronto and The Township of York, 1885, pp. 461-462)

YOU CAN’T HAVE HIM! OH YES I CAN!

When Josephine Leslie ran off with her lover, Edmond J. Clarke, her family brought charges of abduction against the man. This was done by families of under aged girls in the Victorian era to protect the reputation of the family.

Edmond John Clarke was born in Toronto around 1851. His parents were English butcher, Edmund John Clarke, and his wife Charlotte. He was their only son. His father died young, leaving Mrs. Clarke very well off, but dependent in many ways on Edmund John Jr. The Leslies and the Clarkes had been neighbours for four years – since the Leslies moved onto McGee Street. The Leslies accused Clarke with “taking Josephine Leslie from the protection of her by fraudulent means”. “Fraudulent” because they alleged that he did not tell Josephine that he had married on Catharine Ann Snarr February 11, 1870 in the Township of York. But it quickly became apparent that Josephine or “Josie” knew that her boyfriend was married but didn’t care. This would have deeply shocked not only her staunch Presbyterian family, but their middle class neighbours and friends. (To the working class folks of Leslieville, “shacking up” was neither new or particularly shocking.)

The Presbyterian Leslies were deeply shocked when Josephine (Josie) Leslie, Robert and Mary Ann’s, 18 year old daughter, ran off with a married neighbour, ten years older than herself. The Leslie family made every effort to keep Josie and butcher Edmund John Clarke separate, including forcibly confining the teenager. She simply threatened to run off to Buffalo with her lover, get a divorce and get married. The family had Clarke charged with abduction and the trial titillated Toronto’s newspaper readers who gobbled up the private details of the love affair and the family’s angst. While George Taylor Denison, the judge in the case, was quite clear that he would imprison Clarke if he could. Denison was notorious:

Usually faced with an enormous caseload, and with little interest in the causes or prevention of crime, he had no use for legal technicalities or procedural niceties. His was “a court of justice, not a court of law,” he proudly asserted. By his own admission, he relied more on intuition than on evidence. Although he liked to boast that he judged impartially, some groups fared better than others: retired soldiers and members of Toronto’s respectable classes could expect leniency but striking workers, parvenus, Irishmen, and blacks invariably received harsh treatment. Denison nonetheless took a paternal interest in the unfortunate members of the lower classes who filed through his court. He championed legal aid, chastised the legal profession for profiting from people’s misfortunes and prolonging cases, and denounced moral reform groups that tried to impose their standards upon criminal elements “who offended their tender susceptibilities.” His unorthodox methods were notorious – his court even became something of a tourist attraction. (Norman Knowles, “DENISON, GEORGE TAYLOR,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 3, 2016)

THE ABDUCTION CASE was a Victorian melodrama played out in courtroom packed with titillated spectators who “appeared very eager to hear the case”.

John Leslie described how he refused to let Edmund Clarke into the Leslie house at 26 McGee Street when the man, ten years older than his sister and married, came a courting. John said, without a trace of irony, “I never abused my sister; I used forcible means to keep her away from prisoner; the night that she wanted to go…when I tried to take off her bonnet she dropped on the floor in a state of nervous prostration.” The family did everything they could to keep the couple apart, sending Josephine to live with her aunt at Bay and Gerrard. (Globe, Nov. 26. 1878)

Clarke called out from McGee Street to Josephine who her family kept under lock and key in her bedroom. When Clarke persisted, John Leslie beat him up; Clarke did not fight back. According to John Leslie’s own words, Clarke was cut about the face considerably, and had a black eye.” Clarke said (and very apparently Josephine agreed) that if he couldn’t get a divorce in Canada, they would run off to the States and get married there.

Robert Leslie seems absent in all of the proceedings, but Mary Ann Leslie testified in court, “We told her that if she associated with the prisoner she would never be respected.” That did not stop the couple from writing each other and seeing each other on the sly. Mary Ann Leslie went through her daughter’s dresser and found the love letters from Clarke. Josie was adamant, telling her mother, that “she would never give up”. Robert Leslie’s opinion was, according to his wife, that “he would rather go to the United States and see them married; in the meantime, if that could not be done, he [Clarke] must not come to see Josie.” According to Mrs. Leslie, Clarke said, “he could take her away in spite of me.” Mary Ann defended son John insisting that he had not physically abused Josie, but admitting that, “her brother James might have given her a little shaking”. (Globe, Nov. 26, 1878)

The Magistrate said he would say something now which might have the effect of causing the defence to alter their plans. He had considered the evidence very fully, and he had heard enough to enable him to form an idea of the facts of the case. he did not know how the evidence for the defence would affect his opinion; but his impression was that he would convict the prisoner unless something of a remarkable character came out.

…At this stage of the proceedings Miss Leslie burst out crying and did not recover herself until after the case had been adjourned and the prisoner removed. (Globe, Dec. 13, 1878)

Josephine was a healthy eighteen year old with a mind and heart of her own, and as determined as the Leslie clan motto, “Grip Fast”. She was not going to let Edmund Clarke go. The jury did not even get up from their seats to retire to the jury room. They immediately said, “Not guilty”, and true to their word, the lovers ran off to Buffalo where they had apparently lived happily ever after, raising children, and living to a ripe old age together. (Globe, Jan. 23 1879)

In perhaps the rest of the family could have used a vacation at the Hotel Calmo (see picture).

MURDER ON McGEE

The “Leslie abduction” shocked people, but there was a far more grisly case, a true crime, and the ghost of Willie Long may haunt McGee Street to this day.

On July 12th, 1882, on the Orange Lodge’s most important night, July 12th, a mob of drunken men attacked a young man outside a hotel near Queen and Leslie. The Orange men held a dance in their room at the back of the hotel. Fights were not unusual; it was a tough neighbourhood. The place had a reputation and brickmakers were notorious for kicking with their steel-toed boots: “…rowdyism and terrorism are predominant in the locality”. (Toronto Daily Mail, July 24, 1882)

William Long, nicknamed “Willie”, did not go to the dance, but drank with friends in the hotel bar. Some men started teasing about Lucy Wise, a young woman from a family on Laing Street nearby. She worked as a servant downtown, but was enjoying the holiday, perhaps too much. Fists started to fly and the bartender through the men out. They were very drunk. People said at the time, “that liquor was at the bottom of it, and that nearly all the parties who were fighting were muddled with beer.” (Globe, July 22, 1882)

The men tried to set up a fight between John Banks and James Ferguson for the next Sunday. Such bare knuckle fights were popular, and an accepted way to settle disputes. But negotiations failed. Willie and his friends started west for home along Queen Street. But the other men caught with Willie. The two groups of men began fighting near Ross Manson’s butcher store. James Ferguson climbed on top of Frank Peterson, and stomped on his leg until he broke it. (Did I mention kicking?)

Willie Long fled west along Kingston Road. Hot for retaliation, four men chased him down. One pulled a revolver and shot at Long, but missed. Long tried to escape by running his home on McGee Street near the railway crossing. He reached the back of his house, but the men cornered him in a narrow space between the house and the outhouse. There four men beat and kicked him into unconsciousness. Eliza Long, the victim’s mother, woke up and came to the back door with a light. There she heard a man say, “Now you’ve got him, give it to him” and her son cry out, “That will do boys, you have done for me.” She ran to her son. As the men were leaving, she heard one of them say, “Let us go back and finish him”. When she reached her son’s side Willie said to her, “Mother, they have murdered me, my face is smashed all to pieces; they must have had steel knuckles.” (Globe, July 21, 1882)

William Long had serious facial and skull fractures and died on July 19, 1882. Long was only 24. If anyone had a reason to haunt McGee Street looking for the murderers who never did time for the crime, it is poor Willie Long.

“SQUIRE” OF McGEE

Robert Leslie was the unofficial leader of McGee Street, just as his brother George fought for the rights of people in the village named after him.

In 1879 Robert Leslie took lead delegation that presented a petition to City Council. They wanted a sewer on McGee Street. (Globe, Dec. 8, 1879) This would have been a combined sanitary and storm sewer, carrying both rainwater and human waste into Ashbridge’s Bay. Their house was squeezed into a narrow plot of land between the railroad and McGee Street and on wet ground, close to Ashbridge’s Bay and the marsh at its west end. The water table was only a few feet from the surface. In 1882, Robert Leslie had “from four to five feet of water in his cellar” and, like other residents demanded that the City put in drains to prevent flooding. (Globe, April 4, 1882) He got what he wanted:

“The laying of the drains is now about completed on Saulter and McGee streets, and the property-owners on Lewis-street will petition to have one laid on that street.” (Globe, May 15, 1883)

Robert Leslie died in 1886. The Globe notes that he left “a wife and nine children, five sons and four daughters, all of whom were present during his last hour”, but he had one daughter who wasn’t there: the black sheep, Josie. Robert Leslie is buried in Toronto’s Necropolis Cemetery where his brother George would be buried a few years later. After his death Mary Ann House (1817-1907) continued to live in the family home, no doubt built by Robert with his sons, at 26 McGee Street.

The area became poorer in the 1890s and the industrialization intense. Smoke from Consumer Gas and other nearby industries made the earth thick, but people saw it differently. Smoke meant people had jobs.

Olwen Anderson was born on nearby Empire Avenue and grew up there in the 1930s. She spoke of her growing up at a meeting on April 24, 1999 at the Ralph Thornton Community Centre. They were poor and instead of coal bought coke at the Consumers’ Gas down the street on Eastern Avenue. They paid around 18 cents for a bushel. Rent was about $30 a month, however, most people bought their own home. It was more secure. If a family paid the interest on their mortgage, the landlord could not evict them. (Toronto Voice. “The Trials and Triumphs of a childhood on Empire Ave.” Toronto Voice, May 1999. In the Local History Collection of Toronto Public Library, Broadview-Gerrard Branch, p. 10.)

And so this story of marriage, murder and muddy McGee Street ends, but another will appear soon as I am researching another mystery related to Morse Street.