by Joanne Doucette This is a follow up to: https://leslievillehistory.com/austin-avenue-subdivision-549-by-joanne-doucette/

Part 1: Austin Avenue blocked by A Creek

Did you know that there was a creek at the east end of Austin Avenue?

In 1918, the foreman of George Leslie’s nursery recalled Leslie Creek:

a creek … also started near the sandpit and ran through the gardens of Cooper’s, Bests and Hunters, crossed the road by the Leslie Postoffice. Here it joined a small creek that drained the nursery, and both crossed Leslie street under a bridge that has since been filled up by intersecting sewers.

John McPherson Ross (1859-1924), Globe, January 18, 1918

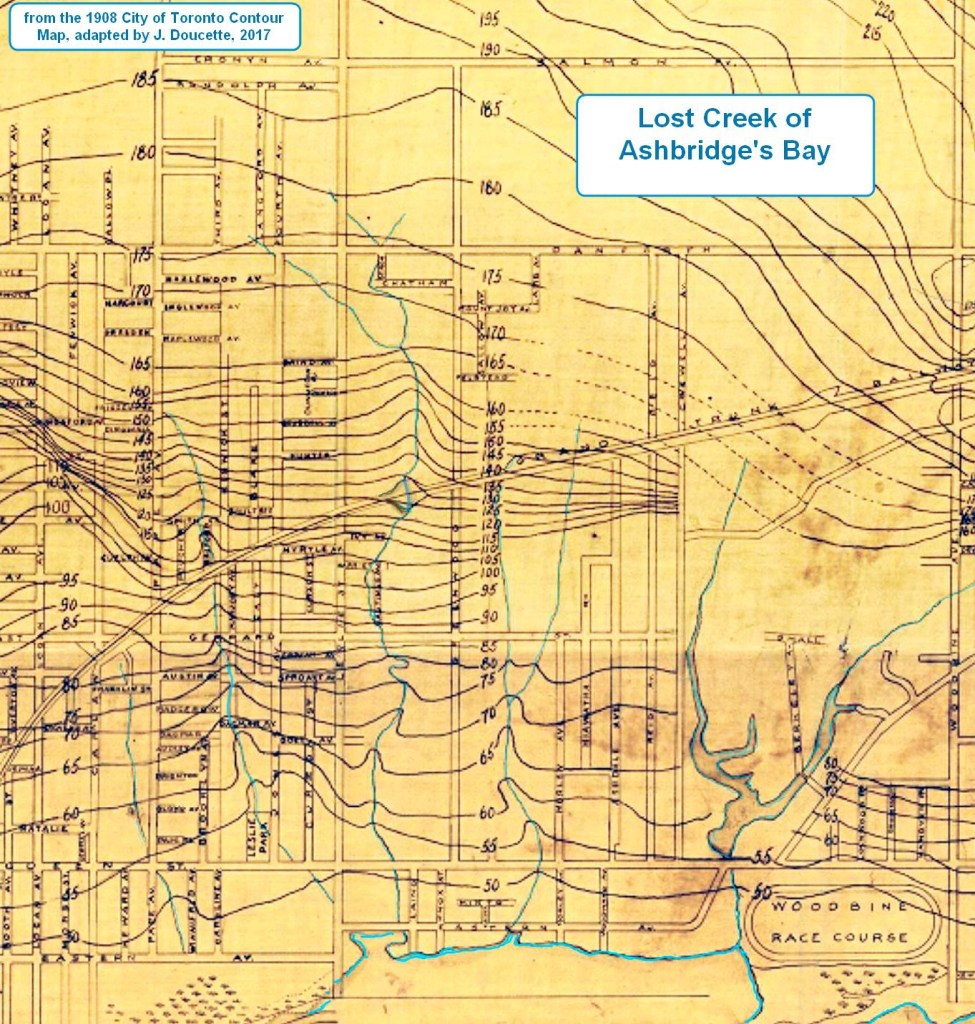

Leslie Creek originated in the area of Strathcona Avenue and Eastview Park from springs on the slope of a sandbar from the last Ice Age.

Over ten thousand years ago, the melting ice dumped sand, clay and gravel (“glacial drift”) on southern Ontario. It is about 26 meters thick over most of Toronto. As the ice melted, a lobe of the glacier filled the basin where Lake Ontario is now. This ice blocked the melt water from draining to the sea down the Saint Lawrence River. The ice was like a plug in a bathtub and a deep, cold melt water lake, Lake Iroquois, formed behind it. This lake was 55 meters (180 feet) deeper than Lake Ontario. All of Leslieville was under water. The Lake Iroquois shore-cliffs form a steep rise or escarpment north of Leslieville. The shore cliff can be seen clearly along Davenport Road and near Variety Village on Kingston Road. It is the long hill on Yonge Street south of St. Clair Avenue, known as “Gallows Hill”. South of this cliff lies a plain of sand deposited on Lake Iroquois’ bottom. Leslieville sits on the Lake Iroquois Sand Plain. The Plain, though tilted is still relatively flat, but far from featureless. Great rivers poured off the melting glacier, carrying huge amounts of sand and gravel into the Lake. There wave action and strong east-west offshore currents carried the sand and gravel westward, piling it up in bay-mouth bars. Behind the sandbars at the mouth of what are now the Humber in the west and the Don River in the east, large bays formed.

In the East End, these sand bars form a ridge that stretches from Scarborough, west from the foot of Kennedy Road for about five kilometers (three miles). The sandbar diverted the flow of Taylor Creek westward into the Don. To the south of it more sandbars formed offshore under water, creating the long hill south of Danforth Avenue from Broadview through Leslieville to the Beach and the sand plain of Leslieville. The settlers mined these glacial beaches for sand and gravel. The sandy loam was the basis of Leslieville’s market garden industry. With compost and manure, it was fertile and easy to till, ideal for carrots, potatoes, turnips and other root vegetables.

Leslie Creek was deeper and faster flowing before settlers deforested the flat, but tilted, sandy plain south of Danforth Avenue. Streams like this cut deep ravines into the loose Lake Iroquois sand plain that made market gardening so lucrative in Leslieville. Erosion exposed clay deposits from an earlier Ice Age, providing the raw material for brickmaking. Some families of market gardeners became brickmakers, like the Logans, while others, like the Papes, remained gardeners, florists and nurserymen.

Part 2: A Skating Rink and Park

According to Elsie Hays, an elderly resident that I interviewed 40 years ago, it was a small brook that ran through an orchard where she used to play with her sister, catching minnows and tadpoles. It crossed Gerrard where there is a shallow dip in the road to mark it. Entrepreneurs dammed the creek in the late nineteenth century to create Maple Leaf Skating Rink at Pape and Gerrard.

Part 3: A Cemetery by a Creek

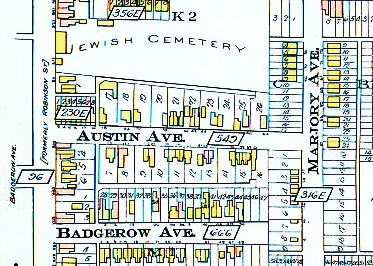

In 1849 Toronto’s Jewish community opened the first Jewish graveyard west of Montreal on the west bank of Leslie Creek. It must have been an idyllic situation.

There is no synagogue in Leslieville but there has been a definite Jewish presence here from the mid-nineteenth century. In 1847 Judah G. Joseph was an optician and jeweler, with a store at 56 King Street East, Toronto. In 1849 his young son, Samuel, was dying and there was no Jewish cemetery nearer than Buffalo or Montreal in which to bury his boy. Abraham Nordheimer, a successful piano manufacturer, and Judah Joseph sought land on behalf of the Jewish community for a graveyard. At the time there were only 35 Jews living in Toronto.

They bought land 60 feet wide and 400 feet deep (about 18 by 12 meters) for £20 through the Chief Justice, John Beverly Robinson. The Robinson family, prominent members of the Family Compact, owned land in the neighborhood. (Part of Pape Avenue was called Robinson Street for some time.) For more about John Beverley Robinson to to: http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/robinson_john_beverley_9E.html

They buried Judah Joseph’s son, Samuel, in 1850, probably near the cemetery gate where the gravestones are all under grass. The grave of Catherine, the wife of Alfred Braham, also buried in 1850, was the earliest Jewish grave in Toronto marked by a tombstone. After 1930 there were few interments, although the cemetery remained in use through the late 1940’s.

The Pape Avenue Cemetery (now known as the Holy Blossom Cemetery) still lies behind high walls, just south of the Matty Eckler Community Centre. This is the oldest Jewish cemetery in Ontario and indeed the oldest in Canada west of Montreal. It is inactive and permission is needed from Holy Blossom Temple to enter. Seven years after the cemetery was founded, the Jewish community established the first synagogue in Ontario in rented premises above Coombe’s drug store at Yonge and Richmond streets. It later became Holy Blossom Temple. In 1919 a new Jewish Cemetery on Jones Avenue, just north of Leslieville, was consecrated, fulfilling an old Toronto Jewish proverb: “Live in the west; buried in the east.”

Part 4: Leslie Creek: from Austin Avenue to the Bay

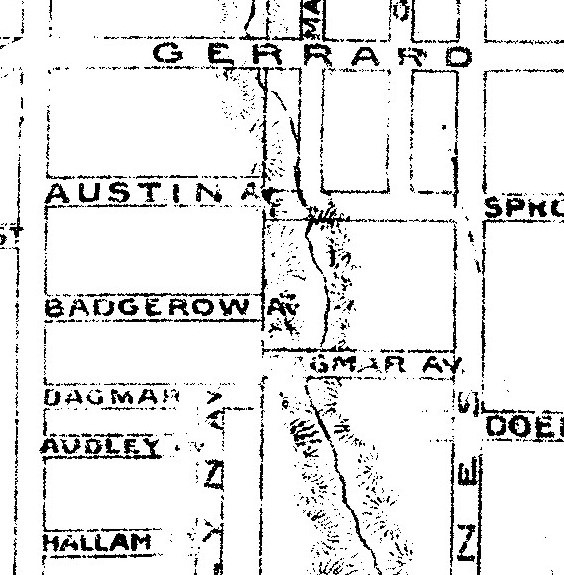

South of Austin Avenue, the creek flowed west of Marjory Avenue to diagonally south east to cross Dundas Street at Dagmar. It crossed at 61 Jones Avenue where there was heavy basement flooding. It ran behind the store front block on the north side of Queen Street (George Leslie’s house and selling grounds) and crossed Queen Street just west of his general store at the northwest corner of Queen and Curzon. It flowed through George Leslie’s nursery to cross Leslie Street and Eastern Avenue to enter Ashbridge’s Bay at the foot of Laing – the Gut. The Gut is where the City of Toronto Works Yard is now.

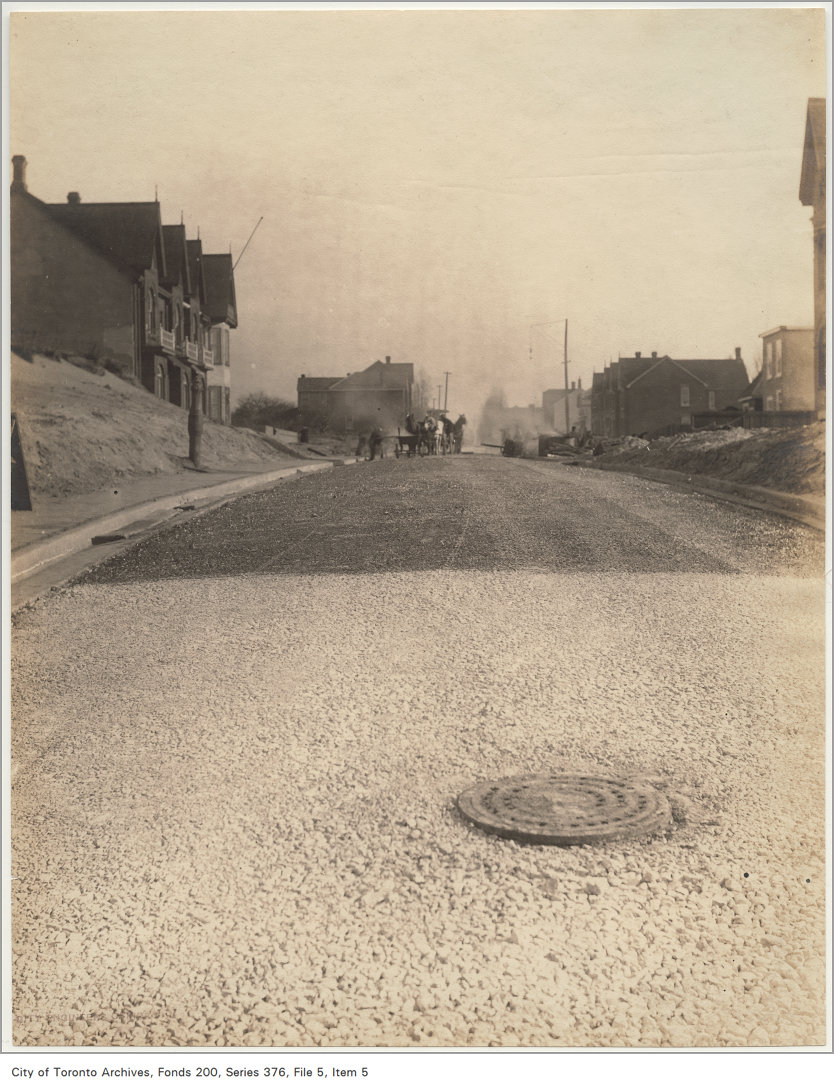

In 1910 city work crews buried Leslie Creek diverting its water into the municipal storm sewer system so that Austin Avenue could be extended. But the creek didn’t die. While water from rain and snow pours into the storm sewers, precipitation also sinks into the soil of gardens, lawns and parks, flowing as groundwater along the course of the old creek. Gone and totally forgotten, wet basements and faulty foundations along its way tell their own story.

Today there’s not much left to see of Leslie Creek, but if you look closely traces of the ravine remain. The dip in the lane way north of Austin Avenue is the old creek bed. If you look into backyards, remnants of the ravine west of Marjory Avenue south of Gerrard. The creek itself can still be heard running underground after a rainfall or in a spring thaw.

Part 5: The Street is Extended

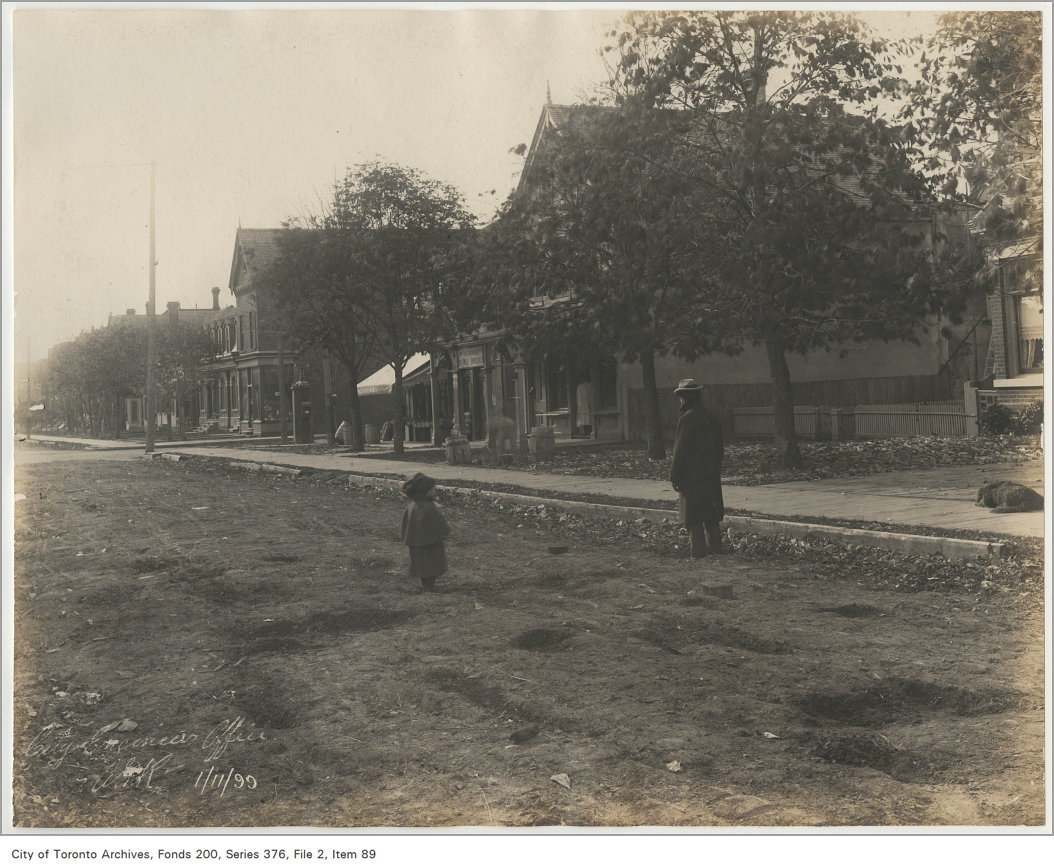

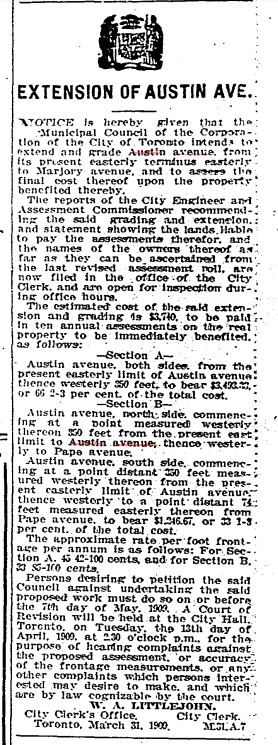

Public infrastructure, which in those days meant sewers, paved streets and sidewalks, was essential to the success of any new subdivision, then and now. George Washington Badgerow believed the East End would become an important and prosperous part of Toronto. Even before he began Subdivision #549 where Austin Avenue is today, he pushed the City of Toronto to improve road access to his subdivision. He succeeded.

Brickmakers deepened and widened the ravine when they dug down to extract clay and sand for bricks. Leslie Creek blocked the extension of Austin Avenue eastward to Marjory until 1910.

New transportation technology demanded new streets.

When Austin Avenue was extended in 1910, the area was a streetcar suburb of Toronto. Under heavy pressure from the City of Toronto, the Toronto Street Railway Company extended its Gerrard line east from Pape Avenue to Leslie Street and, after that to Greenwood Avenue, but no further.

The private streetcar company’s line was extended from Pape to Leslie in 1906 and to Greenwood in 1909 The City of Toronto built its own Civic Car line from Greenwood Avenue to Main Street. In December 1912, the new line opened. Soon after the City built a streetcar line from Broadview to Main along Danforth Avenue. Like Badgerow, others could see a bright future for the East End.

And then people could see that this part of the east-end was being brought very, very near to downtown, and that it was a beautifully wooded stretch of land. The cars discovered Gerrard street. They have taken hundreds of home-site buyers and builders down there. Toronto Sunday World, December 22, 1912

But by the time Austin Avenue reached Marjory Avenue, there were over 2,000 automobiles registered in Canada – a mere handful, but by the outbreak of World War One there were over 50,000. Cars, the new technology, demanded the developed of a different kind of city street, one that could accommodate the wear and tear of mechanized transport.

Not everyone was in favour of improving roads. Some rural residents resented Torontonians and their noisy automobiles. In 1903 York County Council considered improving the roads, but:

Councillor Baird stated that he was very much opposed to paying out money for good roads and then have “the automobile fellow” come out on them from Toronto. He stated that these machines went at a terrific rate, and were very dangerous.” Toronto Star, November 27, 1903

The automobile revolutionized Toronto’s cityscape, transforming the gravel and sand roads of the earlier rural Leslieville and even the more recent “streetcar suburbs” created by the extension of the streetcar system, especially the Civic Car line along Gerrard. It is not coincidence that people in the East End stopped thinking of their community as “Leslieville” around this time.

Sheet asphalt placed on a concrete base was first used in Paris, France in 1858 and first used in the U.S. in 1870. Thirty years later bitulithic pavements, a mixture of aggregate (crushed rock or gravel) and crude oil, began to be laid in Toronto. At first the binder was produced using naturally occurring crude oil (mostly from Trinidad), but in 1907 manufacturers began producing asphalt binders synthesized from petroleum. By the 1920’s many of Toronto’s streets were paved with asphalt. Portland cement (a mixture of cement, sand and gravel) was also being used in road construction, as a base to support wooden block paving, bricks, cobble stones, granite blocks, etc.

Local improvements could get expensive, especially when streets were extended. The ravine of Leslie Creek cut across the east end of Austin Avenue severing it from Marjory Avenue until 1909. The Russell family of brickmakers mined the banks of Leslie Creek for clay. Marjory Russell is believed to be the source of the name for this local street.

Austin Avenue was paved using new technology, but an old material: asphalt, a mixture of bitumen (crude oil) and aggregate, rolled on to streets hot. As automobiles began to multiply, drivers began to demand better roads and streets. Before asphalt this, the City of Toronto paved its streets with bricks (yes, there really were yellow brick roads), granite or wooden blocks. But the kind of pavement laid down in 1910 on Austin Avenue gave a smoother ride.

A writer in 1716 said, “Tis impossible to be sure of anything but death and taxes.” After the City of Toronto filled in the ravine of Leslie Creek and extended Austin Avenue to Marjory Avenue, property values went up as did tax assessment on Austin Avenue and Marjory Avenue.

Death is still with us and I wonder what the taxes are on theses Austin Avenue houses?

https://torontolife.com/real-estate/sale-of-the-week-39-austin-terrace/

https://www.blogto.com/city/2013/04/house_of_the_week_41_austin_avenue/

http://55austin.com/