ASHBRIDGES BAY

from MUD ROADS AND PLANK SIDEWALKS: LESLIEVILLE 1880

By Sam Herbert (1876-1966)

Ashbridges Bay teemed with fish and wild life. My favourite fishing spot was from the pilings outside the large ice house that was located at Leslie Street and Eastern Avenue, where the paint works is now located. It was a splendid place for sunfish, perch, bass, and catfish.

Two or three days a week after school, enough fish could be caught for a couple of good meals. This all helped out.

![Sunset on Ashbridge's Bay. - [1909?]](https://leslievillehistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/sunset.jpg?w=1024&h=702)

It seemed to be open season all the time for fishing, and almost every home contained a shotgun, some of them, the old muzzle-loading variety with shot, powder pouch, and ramrod as necessary equipment.

In the Fall, ducks came down in thousands to the Bay, and were shot for the market as well as home use. Many a duck hunter making quite a tidy sum from the sale of them, as well as providing for their own table. Duck hunting was not all fun, pushing out the boat, arranging guns and decoys, rowing out to the “Blind” in perhaps a cold rain, or sleet on dark morning. Then arrange the decoys, and make oneself as comfortable as possible while waiting for daylight, and the quack quack of the incoming ducks over your decoys. Many a cold and more serious illness could be traced to the annual or semi-annual duck hunt.

In winter, skating and iceboating on the Bay were the regular pastimes. The icemen reaped their harvest at that time as well. Ice, eighteen inches to two feet thick would be cut in large squares, hauled out and taken to the icehouse where it would be packed in sawdust until the following summer. Small evergreen trees were placed where the ice had been cut, and were the danger signs, so that skaters and ice boats would keep clear.

Some breath-taking speeds were attained with ice boats.

They had cushions and were quite comfortable, but fur caps were a necessity. People did not go around in their bare heads in those days even in summer.

The Bay and adjoining ponds provided most of the skating needs, and on Toronto Bay, Ashbridges Bay, and the numerous ponds adjoining the Don River “Shinny on your own side” was the game, only we did not have the machine-made sticks as used to-day for hockey, but one would go to the nearest bush and select the proper sized stick with a curve in it, bring it home and trip it up to their individual tastes.

In the marsh around the Bay, muskrat trapping was a recognized industry, and muskrat lined coats were very common, especially those with the large beaver collar, and when I say beaver, I mean beaver.

In the winter, when the rushes and reeds were dry, marsh fires were very common, and often the sky was darkened with the heavy black smoke, but very rarely any real damage occurred.

The Don River at that time was a winding crooked stream with many ponds near it. The water was clean and clear. Then it was decided to straighten the Don. It was surveyed, and soon the huge steam pile driver got to work sending down long posts side by side deep in the ground. These posts still form the shores of the Don although time has broken many of them away. I have caught many good strings of perch, sunfish and catfish while sitting on the posts of the newly straightened Don River.

At one time a ferry boat plied the Don River from the Gerrard Street bridge to the island. Captain James Quinn was in charge of the ferry “Arlington” which sailed between Toronto Island and up the Don River to the Gerrard Street Bridge. The Arlington was a fair-sized boat that would accommodate at the most about a hundred passengers.

It was a nice trip, but the patronage did not warrant its continuance.

The Don was a wonderful place for small boats and canoes.

ANOTHER FIRST HAND STORY OF ASHBRIDGE’S BAY

PICTURESQUE ASHBRIDGE’S BAY MAKES WAY FOR INDUSTRY

Vast Changes Being Made in East End of Toronto

LOOKING BACK FIFTY YEARS

Haunt of Pike Fishermen, Pleasureseekers and Birds Passes to Man

(By J. McPherson Ross)

Globe, Tuesday, January 8, 1918

Ashbridge Bay, as it appears on the map of Toronto, was a beautiful sheet of water when I first saw it in the summer of 1863, and was clean and good enough to drink, abounding in fish, and was the haunt of numerous wild fowl all summer. In the stormy, rainy fall, it was alive with wild ducks of all kinds that came to rest on their southern flight and to feed on plentiful masses of wild rice that grew in numerous patches. The marsh covered the shallow waters of the eastern part of the bay at the commencement of the sand bar by the foot of Woodbine avenue, as this roadway is now called. When the racetrack of that name was first built the marsh growth ended where the deep water started, and began again intermittently a little west of Leslie street. It was quite a fine sheet of water, and at the time of speaking the lake had made a cut at about the size of the present entrance.

On days when the east winds were throwing up big breakers on the Island quite strong seas came sending over the bay, sufficient sometimes to wash out by the roots large poplars that grew on the street now called Leslie. In those times several creeks added their quota of waters to the bay. The overflow of Small’s Pond and a small creek at about Kenilworth avenue ended in the marsh, another one came through Ashbridge’s farm. One coming through Hastings’ and crossed the Kingston road and emptied into the gut, as it was then known. This gut was quite a sheet of water and formed a little harbor made use of by the fishermen who lived near it, and who ran their boats up the channel to the back of their lots which ended on the water.

Many a large sailboat might be seen those days at any time near the sidewalk on the Kingston road, later called Queen street. Quit a colony of fishermen lived near by, among whom we remember the names of Doherty, Laings, Marsh, Goodwin, Crothers and others who, if not fishermen, were duck-hunters or trappers. Or they also enjoyed the boating, fishing, and bathing privileges which were here in all their primeval abundance and purity of nature become becoming soiled and destroyed by the sewage and filth of the encroaching city.

Creeks to the Lake.

Another creek started near the Danforth road and rand near the sandpit down through several market gardens, crossing the Kingston road at the foot of Pape’s lane, by a big willow tree that grew there on the south side, and ended its journey in the marsh that came almost to the road. This marsh was filled with willows, alders and other growths that made quite a thicket, and was the roosting places of many wood-ducks and other denizens of this safe, marshy, woodland retreat, such as the bittern, woodcock, snipe, plover, sandpipers, and crow blackbirds or grackle. In fact, here and elsewhere wild life was teeming, and the naturalists of those days might revel in the enjoyment of their favorite study. The marsh continued south and was unbroken till it ended at the Island, then went westward, with the exception of a patch of clear water of several acres’ extent, known as Brown’s Pond, which skirted the shore edge of such properties as Heward’s, Gorrie’s, Blong’s, Clark’s and ended with Smith’s, which also ended on the Don River.

I omitted mentioning a creek that also started near the sandpit and ran through the gardens of Cooper’s, Bests and Hunters, crossed the road by the Leslie Postoffice. Here it joined a small creek that drained the nursery, and both crossed Leslie street under a bridge that has since been filled up by intersecting sewers.

A Place for Recreation.

The Ashbridge Bay and the marsh in those days was a very important feature as it furnished the residents of the neighborhood a place for recreation for old and young of both sexes. There were always plenty of boats owned in the vicinity, and for hire. In the long summer evenings boating parties were the favorite amusements till late at night. Music and singing filled the air and echoed along the shores. The plaintive strains of “Nelly Gray,” or “Willie Has Gone to the War,” to the accompaniment of accordeon or concertina, were usually the favorite songs, sometimes varied with “The Charming Young Widow I Met on the Train,” or “Molly Brown,” the last a pleasing melody of the time much favored by the sentimental lads and lassies of the day. Especially on the moonlight nights, the placid waters of the bay would be well patronized, and the air made melodious by the songs just mentioned, while in the darker reaches of the marsh you could hear the drooping notes of the coot and the harsh cries of the mudhen.

Peculiarly weir and picturesque would be scenes in the marsh before the spring growth had started, when parties would go spearing pike. Generally always two, one had to paddle, while the spearer would stand in the bow. An iron contrivance called a “jack,” filled with several pine knots in full blaze, was fastened in front of the boat, and threw a lurid flame on the dark waters below, revealing a gliding pike, attracted by the light and coming to his speedy death, for the skillful spearer impaled in on his barbed spear. On dark nights in early spring it was a common sight to see a dozen or more parties, with the jacklights flitting slowly over the marsh, like so many will-o-wisps luring the fish to their doom.

But when the marsh was frozen hard, busy scenes were enacted. Men could be seen cutting and gathering the marsh hay, to be used for bedding horses or for stuffing mattresses. Great quantities were frequently used for core making in the foundries of that time.

Joy of Skating.

The main part of the bay, when the ice was clear, and before it was thick enough for the ice harvest, would be covered with hundreds of people skating, and the merry shouts of the boys as they skated and played “shinny” made a lively and tumultuous sight, while ever and anon would come a booming sound as the pent-up currents of water underneath surged heavily against the imprisoned top. Oh, the joy of those days that the writer recalls—to be young and strong, with a sharp pair of skates fastened to your top-boots and the long straps securely crossed and buckled tight, and a clear mile of smooth ice before you to go bounding over; a strong shinny and a puck of hard maple to knock, dodging and twisting over the glassy surfaces. The joys of the present youth have nothing on those bygone thrills. As the ice got thicker the little houses of the fishermen would appear scattered over the bays, in spots selected, where the currents brought the wily pike. Here inside in the dark would sit a hardy fisherman, smoking his tobacco, black and strong, now mostly used for chewing as the lighter of yellow kind was not then in ordinary use. The water would be full of greenish light, and the fisher, either with hook or spear, watched this spot with catlike faithfulness, his patience being fully rewarded when he would land a seven or eight pound pike.

The Iceman Comes.

When the ice got to be six to eight inches, then the icemen appeared and several parties would commence the winter harvest. Great ice-houses in those days lined the bay at convenient spots for floating in the crystal blocks. This continued for several weeks, and was a busy time while it lasted. They generally saved all that the modest city required in those days, and it was not till the mild winter of 1880-81 that efforts were made to secure ice, outside, from Lake Simcoe, for the usual supply. Ice was cut, though, for many years afterwards till it was finally stopped by the city officials as being unfit for use. Up till then crowds of men and teams were kept busy in the operations of the ice harvest by the different companies engaged in that business.

Trotting on the Ice.

Trotting races were held for many winters on a mile track laid out on the bay which used to be black with the crowds of sports that patronized this amusement. Wooden shacks were constructed on the ice for furnishing refreshments to the thirsty. Whiskey was cheap and plentiful and sold openly, along with beer, and joy was unconfined for those that liked their spirits. The surviving members of that class think back with pangs for those were the good old days! Trappers got plenty of muskrats and it was a common sight to see numerous figures out in the marsh with a bag on their shoulders and a spear-like weapon to dig out the rats from their winter houses or catch them in traps set for the purpose.

Polluting the Waters.

The first element to spoil the purity of the bay waters was the liquid excreta of the cattle byres which were built by the marshside a little east of the Don to use surplus hot swill, a by-product from the distilleries after the spirits were distilled. This waste liquid manure was run off into the bay and so sullied its waters as to lead to damage suits, which were entered against the company by boatmen whose business were affected, claiming they could not hire out their boats as the fishing was spoiled. Other parties also claimed damages on property grounds, claiming that they byres prevented sales of land, the renting of houses, from the very nature of the business and the general unsightliness of the plant or buildings. The claims were settled for certain monetary considerations accepted by the plaintiffs and the planting of several rows of quick growing trees to hide the unsightly buildings. The nuisance still remained and was a great detriment to the fair name of the east end from that day to this, besides hiding the pollution of a considerable area of the bay or marsh.

The opening of Eastern avenue and the building of the houses, coupled with the necessary sewage from the different streets, fouled all the water, which soon came to be little better than an open cesspool. This created such an outcry from the public that the Keating Cut was made along the face of the windmill line to make a current from the lake to the City bay, which somewhat improved the sanitary conditions for a while. The city began to fill portions of the front marsh with garbage and excavations which made solid land, but previous to this the Government made some improvements as a piling from the Don outflow over to the Island, which formed a roadway that enabled summer residents on Fisherman’s Island to go back and forth to their homes. The boundaries of the marsh proper began to shrink and many schemes were advocated to improve and use the Bay.

Scheme for Improvement.

One that made quite a stir and attracted a good deal of public attention was the Beavis-Redway proposition, which proposed to solidly fill in parts and sell them for factory sites. The straightening of the Don, a much-needed improvement, was gone on with and drew attention to the bay portion. Drydocks and floating docks were partly gone on with, but the interest died away, and with the failure of the Beavis-Redway idea, and matters were allowed to stay still until the sewage disposal plants were discussed and, in spite of considerable opposition this abomination of abominations was finally located at the extreme east end, to be what is was supposed to be, and is to-day, a vile nuisance to the long-suffering neighborhood that had every undesirable business thrust upon them. Every unpleasant enterprise suggested was sure to be located over the Don, such as oil refineries, tanneries, blue factories, packing houses, and, to brief, all that was nasty found an abiding place over the Don that already rejoiced in the jail, smallpox hospital, grease-rendering plants, dead animal receptacles, and many other occupations. The supine representatives in the Council for the east end were unable or helpless to combat.

The establishment of the septic tanks was the last straw, the crowning disgrace to be placed there. The poor old bay got is quietus as a place of recreation and became a place to be shunned, and what was a place of pleasure on holidays for many to enjoy a day of fishing or rowing, or sailing, or in the winter season for skating or ice-boating, became a place to be avoided winter and summer.

The New Life.

But let’s forget it and turn to what will be the proper future and what will drive the septic tanks to a more suitable situation – the great works being carried out by the Harbor Commission. Where the tall rushes swayed in the summer breezes, that swept over the marsh surface, or moved by the eastern gales, as the wavelets died or sank into calmness, amidst the thickening green, where the feathered and animal life pursued their natural ways so beautifully described by the their loving biographer, Sam. Wood, from the days when the feather Indians of the past trapped the wily duck and speared the toothsome pike, down to the last year or so, where nature reigned supreme, what a change has taken place! Great, broad paved streets, several of them running from the city gay, easterly, for nearly a mile, with concrete walks, flanking each side; trolley poles and tracks for street cars up the centre of the streets; immense factories, foundries, and munition buildings greet you on every hand. There are wide canals with concrete embankments, with broad platforms on the sides, all inside a few years; shipbuilding plants and several ships in various stages of completion.

Wonderful indeed have been the changes that money machinery and men have accomplished. All these and more are to be seen, giving an earnest of what it will be when finished.

![Railway Lands - new concept. - [between 1977 and 1998]](https://leslievillehistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/toronto-harbour-commission-4.jpg?w=300&h=210)

Gone are the muskrats.

Gone are the muskrat houses, gone are the acres of brown marsh grass that used to give weird lights when set on fire by the skaters as they lighted it for pure fun. Gone are the gleaming waters of muddy grey as they looked after an eastern blow. So go the times, as with a sigh for the memory of old rambles and boating excursions come into mind, we welcome the new order that has transformed this waste of water sand marshes into a busy hive of industry. This is what those tall columns of smoke that towered over the lake or drifted with the varying breezes meant; the pound-pound of the pile-drivers as they drove the long piles deep into the muddy bottoms.

Good-bye, old Ashbridge’s Bay, you are no more. Good-bye to the rubber-clad duck shooters and the skiffs. Good-bye, coot and coween and mudhen; good-bye, pike, catfish and perch; good-bye, killdeer, yellow-leg and plover, crane, loon and heron. Only the lazy, flying gulls that go sailing over from Toronto Bay and up the Don are all the bird-life or any other wild life, excepting the saucy sparrows that chatter and fight over some workman’s crust. Even their day has come, as the motor truck and speedy auto will soon drive their old friend, the horse, that furnished their principal sustenance will go also into oblivion along with many other things that live now in the classics of your faithful chronicler, Sam Wood. Peace to his ashes.

Globe, Tuesday, January 8, 1918

St. Joseph’s Roman Catholic School came early to Leslieville, about 1863. The first school was a clapboard frame building on Curzon Street, a little north of Doel Avenue. It was mainly the work of Father Rooney, at that time priest of St. Paul’s Church. As a parish priest, he was extremely active in school matters, and for many years was Chairman of the Separate School Board.

St. Joseph’s Roman Catholic School came early to Leslieville, about 1863. The first school was a clapboard frame building on Curzon Street, a little north of Doel Avenue. It was mainly the work of Father Rooney, at that time priest of St. Paul’s Church. As a parish priest, he was extremely active in school matters, and for many years was Chairman of the Separate School Board.

In the mid-1850s land speculators, including George Leslie, laid out housing subdivisions. George Leslie subdivided some farm land in the late 1840s north of Kingston Road between Leslie and Curzon Streets. This subdivision was mostly Irish and Catholic. This subdivisions filled with small houses and market gardens, piggeries and brickyards. Catholics, mostly butchers, including the Hollands and a few market gardeners, like the Wilds, lived here close together. The subdivision north of Kingston Road (Queen Street East) was in the Township of York, County of York. Later subdivisions south of Kingston Road were in the City of Toronto.

In the mid-1850s land speculators, including George Leslie, laid out housing subdivisions. George Leslie subdivided some farm land in the late 1840s north of Kingston Road between Leslie and Curzon Streets. This subdivision was mostly Irish and Catholic. This subdivisions filled with small houses and market gardens, piggeries and brickyards. Catholics, mostly butchers, including the Hollands and a few market gardeners, like the Wilds, lived here close together. The subdivision north of Kingston Road (Queen Street East) was in the Township of York, County of York. Later subdivisions south of Kingston Road were in the City of Toronto.

In February 1874 The City of Toronto Board selected a site “west of Messrs. Leslie & Sons Nursery” on the northeast corner of Eastern Avenue and Pape Avenue. Aug 24: The two-room school was first called South Park Street School, but was soon officially named Leslieville School. The school was also sometimes referred to as Willow Street School, because it was at Willow Street and Eastern Avenue. Oct: Leslieville School opened. That year the log County #6 schoolhouse was replaced with a typical red brick one-room school house. The trustees enlarged the brick school over the years until in 1962 it was replaced by the current school on the same site.

In February 1874 The City of Toronto Board selected a site “west of Messrs. Leslie & Sons Nursery” on the northeast corner of Eastern Avenue and Pape Avenue. Aug 24: The two-room school was first called South Park Street School, but was soon officially named Leslieville School. The school was also sometimes referred to as Willow Street School, because it was at Willow Street and Eastern Avenue. Oct: Leslieville School opened. That year the log County #6 schoolhouse was replaced with a typical red brick one-room school house. The trustees enlarged the brick school over the years until in 1962 it was replaced by the current school on the same site.

In 1883 the Leslieville (Willow School) school had 93 students and 2 teachers with an average of 47 students per teacher. This school was considered overcrowded.

In 1883 the Leslieville (Willow School) school had 93 students and 2 teachers with an average of 47 students per teacher. This school was considered overcrowded.

Our nearest drug store in 1880 and 1881 was near the corner of King and Berkeley Streets, it was kept by a druggist named Lee, and was next door to Little Trinity Church Parsonage. The building is still there. This will give an idea of the conditions in the early days.

Our nearest drug store in 1880 and 1881 was near the corner of King and Berkeley Streets, it was kept by a druggist named Lee, and was next door to Little Trinity Church Parsonage. The building is still there. This will give an idea of the conditions in the early days.

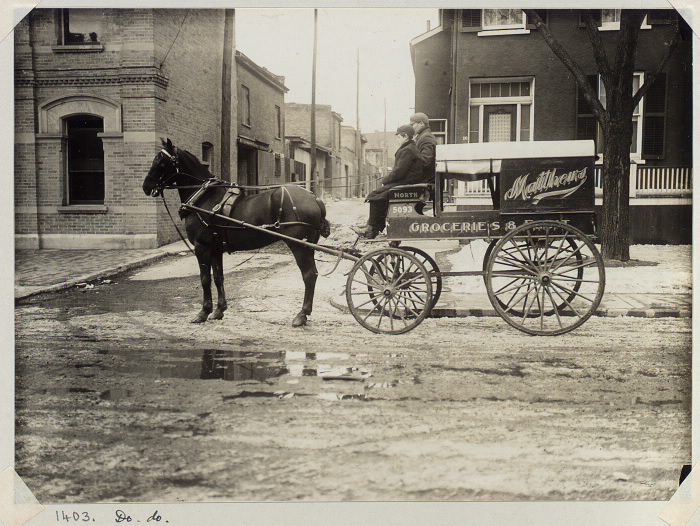

![[A.E.] Gubb Brothers, 370 Rhodes Avenue, Roman Meal window.](https://leslievillehistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/f1266_it21316.jpg?w=1200)

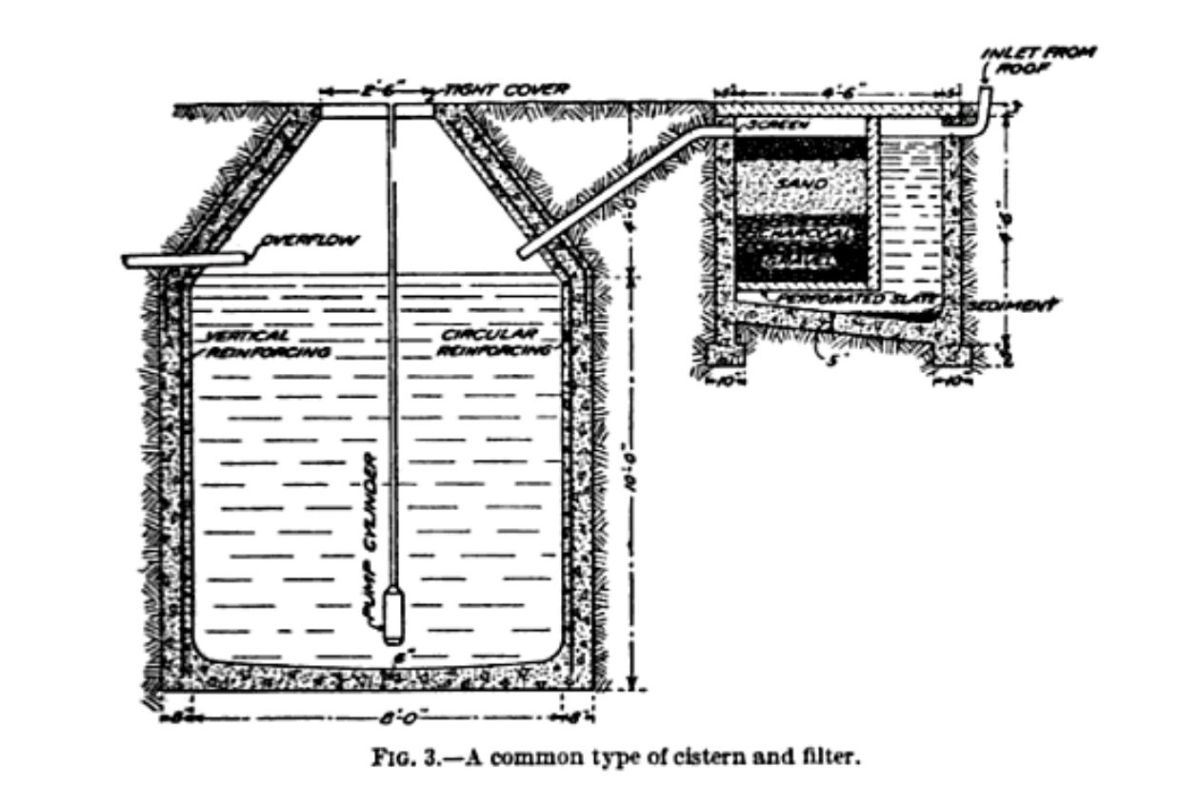

Our water supply was from a well for drinking purpose, and a large cistern and rain barrels for washing. The cistern was sunk in the ground, the top being slightly above the ground level. It was boarded over, and had a small lid in the centre that lifted off when water was required. I remember on one occasion when dipping up a pail of water, I found the body of a skunk floating. I lifted it out and took it to the end of the garden to bury later on. The lid of the cistern had not been replaced properly and acted as a trap. It all taught us all a lesson as it might have been a child instead. We were without soft water for some time, except from the rain barrels on the other side of the house, while the cistern was being pumped out and cleaned.

Our water supply was from a well for drinking purpose, and a large cistern and rain barrels for washing. The cistern was sunk in the ground, the top being slightly above the ground level. It was boarded over, and had a small lid in the centre that lifted off when water was required. I remember on one occasion when dipping up a pail of water, I found the body of a skunk floating. I lifted it out and took it to the end of the garden to bury later on. The lid of the cistern had not been replaced properly and acted as a trap. It all taught us all a lesson as it might have been a child instead. We were without soft water for some time, except from the rain barrels on the other side of the house, while the cistern was being pumped out and cleaned. Outside conveniences was the rule, we did not know about anything else, except in case of illness, when the “chamber” was used. This was also a part of the equipment in every bedroom.

Outside conveniences was the rule, we did not know about anything else, except in case of illness, when the “chamber” was used. This was also a part of the equipment in every bedroom.

The outhouses were all of the regulation two-hole type with a hinged drop cover over each. Of course there was a hook on the inside for the occupant to use, but there was also a wooden button on the outside to secure it when not in use. Sometimes that wooden button on the outside would be cautiously moved to the closed position while the house was in use, and then the indignant cries from the inside to be let out, and the dire results if the culprit was caught. There were quite a few broken buttons on the ground outside.

The outhouses were all of the regulation two-hole type with a hinged drop cover over each. Of course there was a hook on the inside for the occupant to use, but there was also a wooden button on the outside to secure it when not in use. Sometimes that wooden button on the outside would be cautiously moved to the closed position while the house was in use, and then the indignant cries from the inside to be let out, and the dire results if the culprit was caught. There were quite a few broken buttons on the ground outside.

![Woman feeding chickens, Oakville. - [1904?]](https://leslievillehistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/women-feeding-chickens-1904.jpg?w=1200)