by Joanne Doucette (liatris52@sympatico.ca)

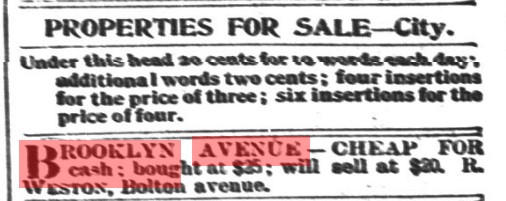

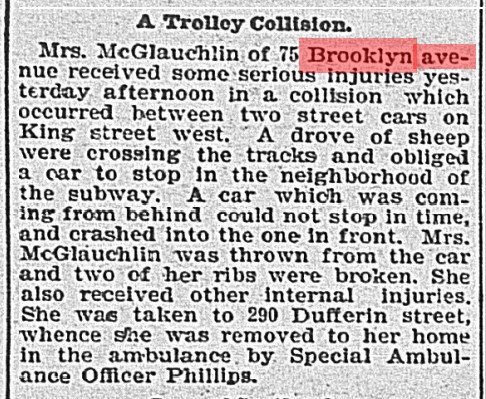

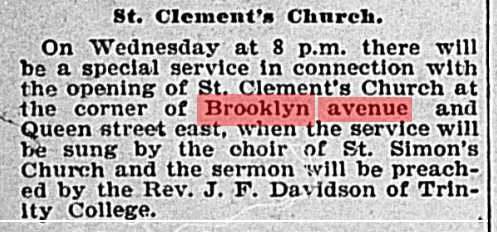

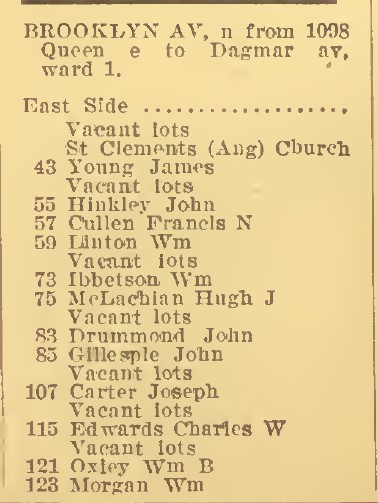

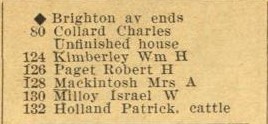

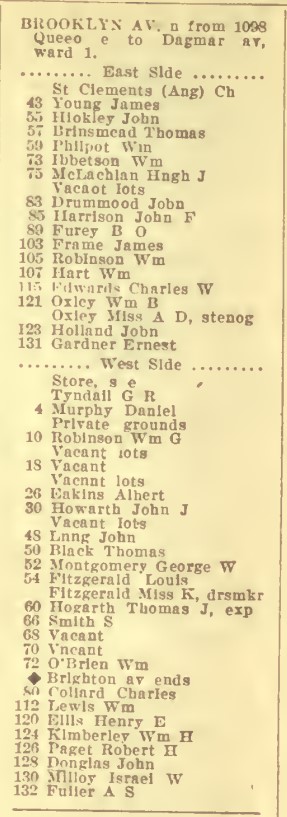

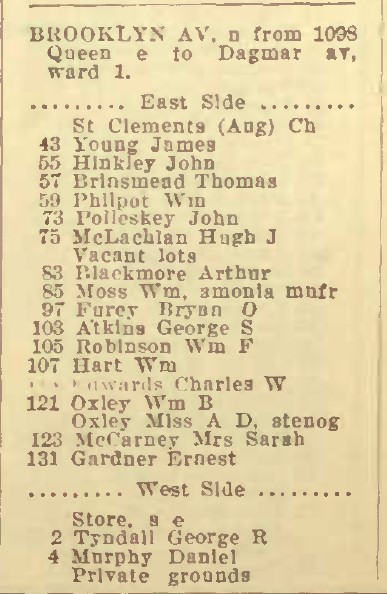

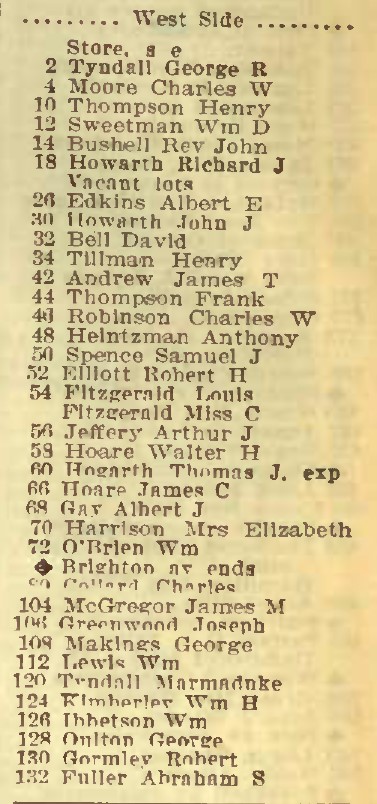

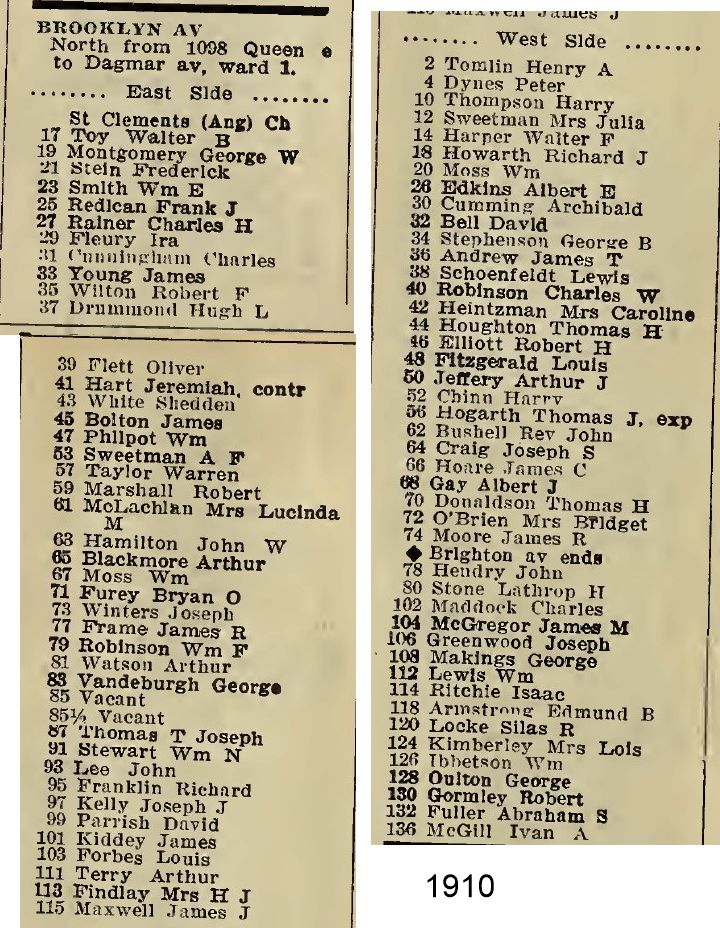

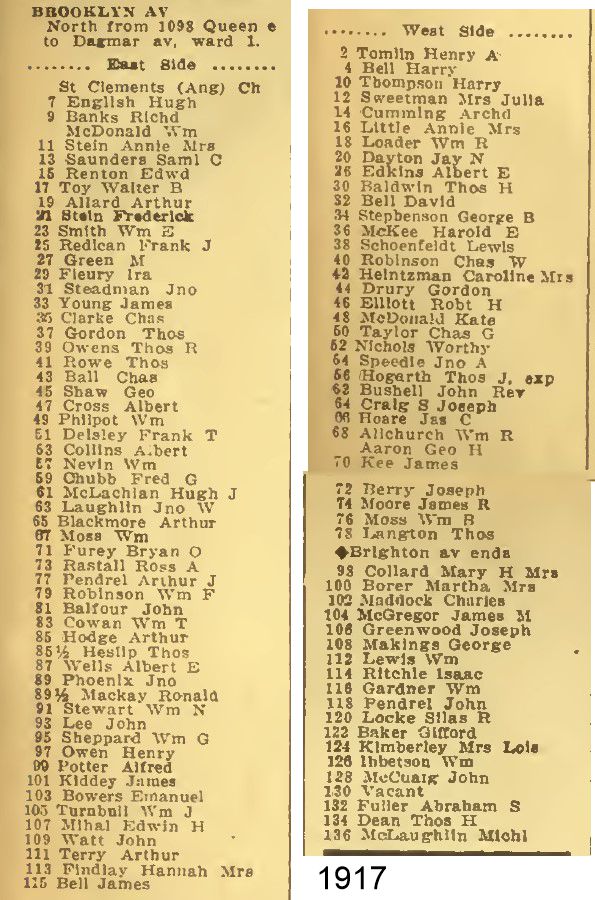

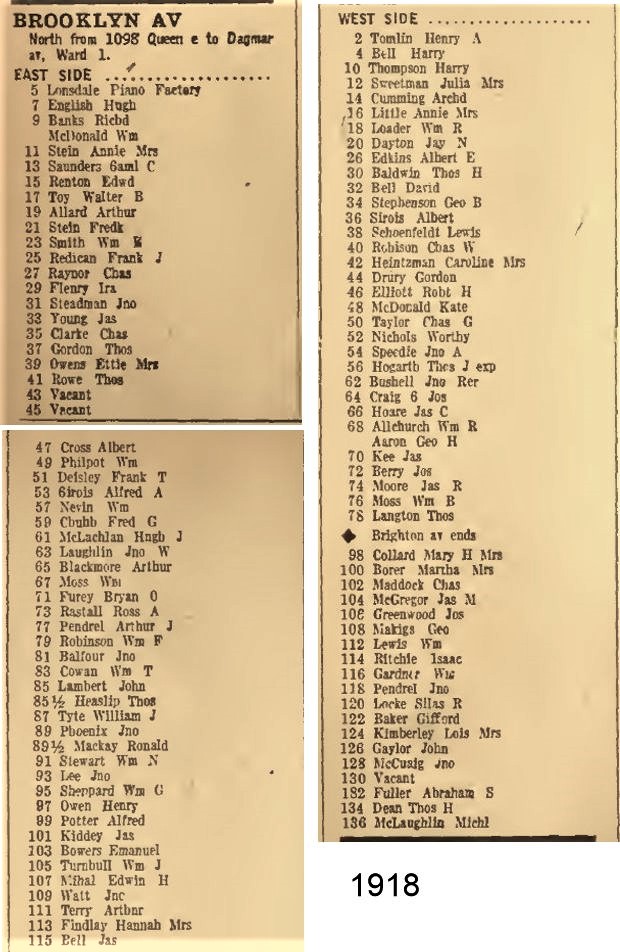

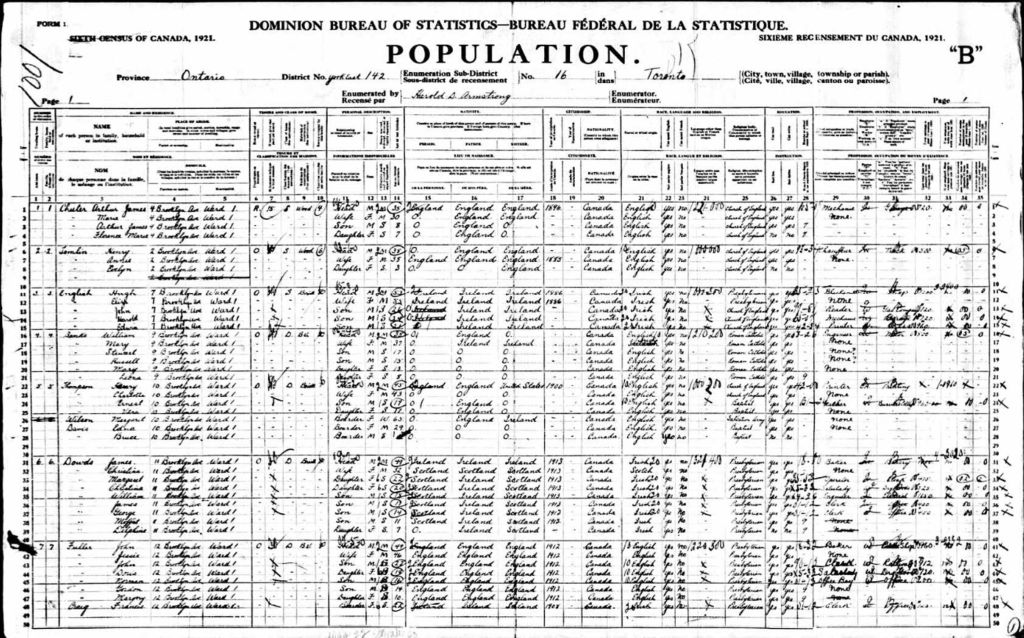

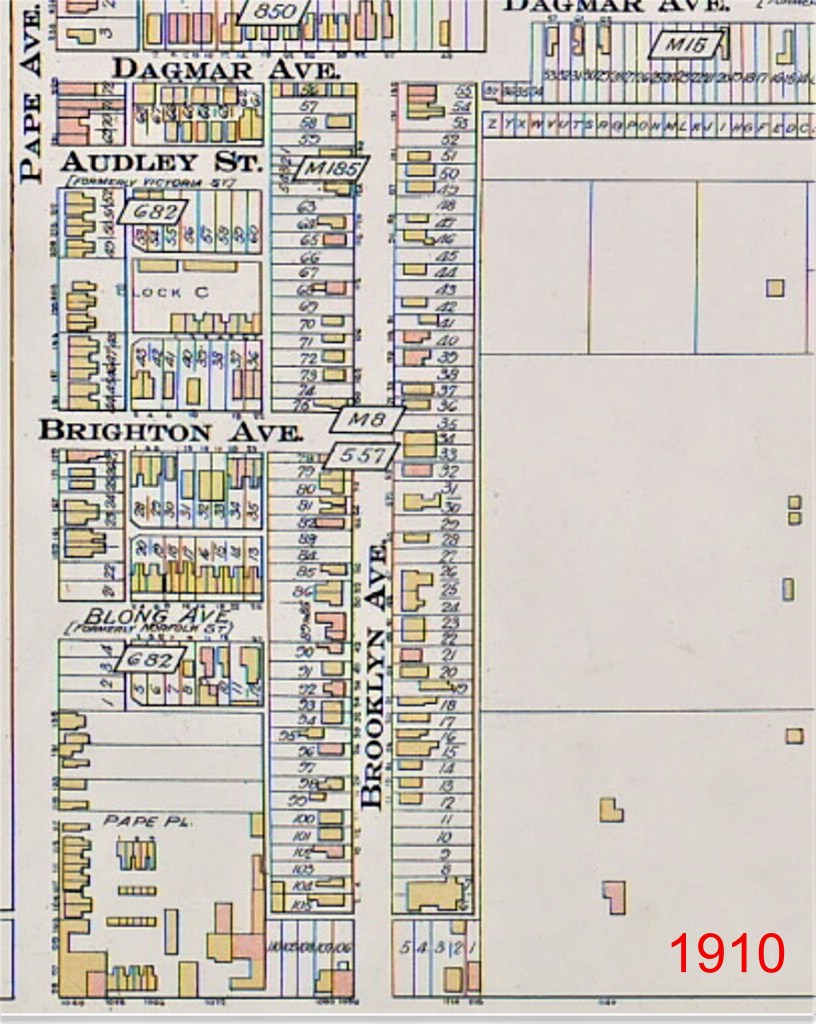

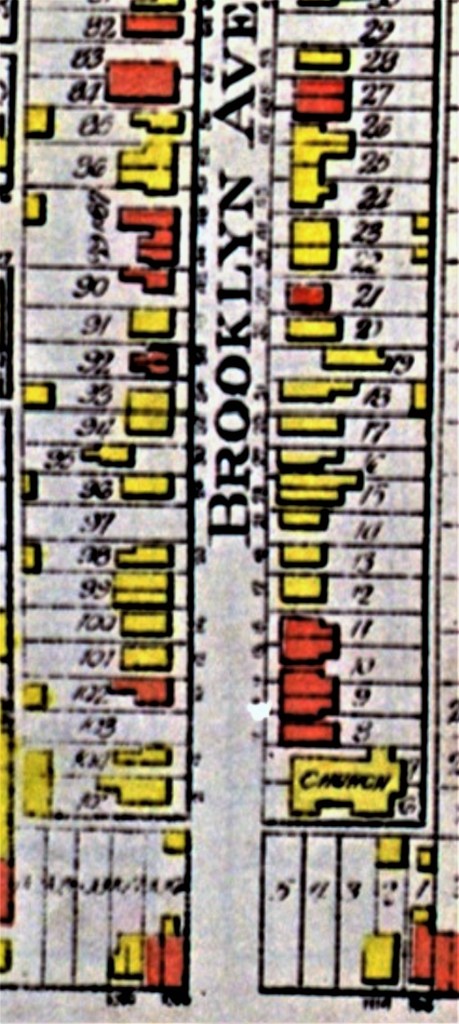

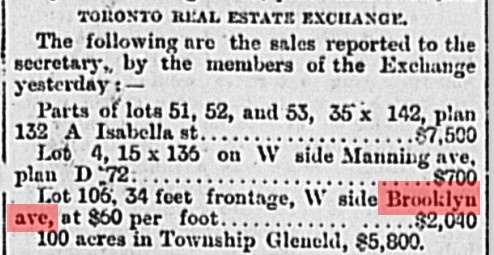

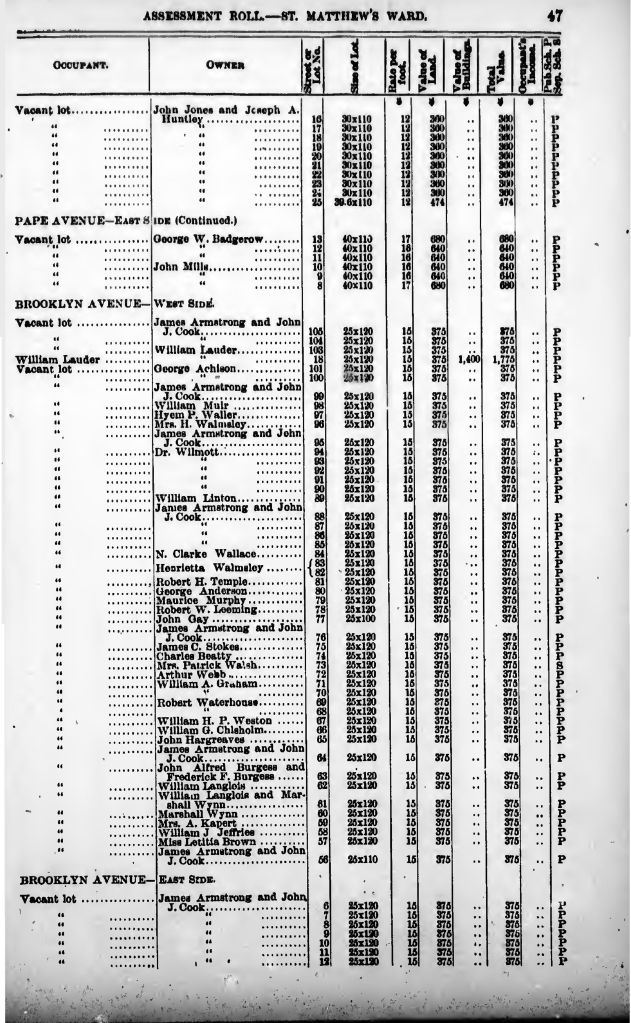

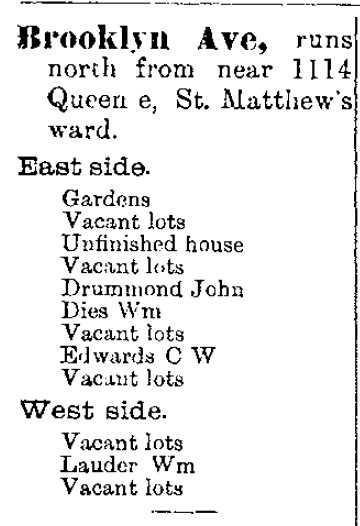

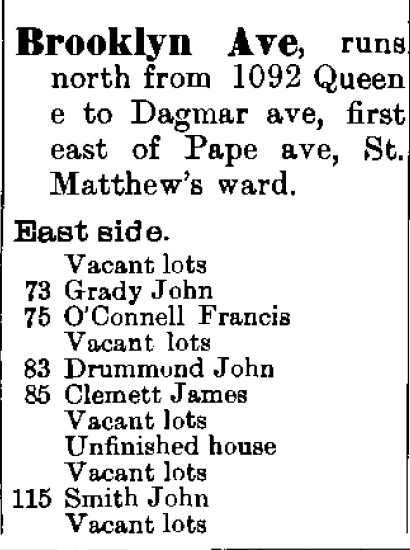

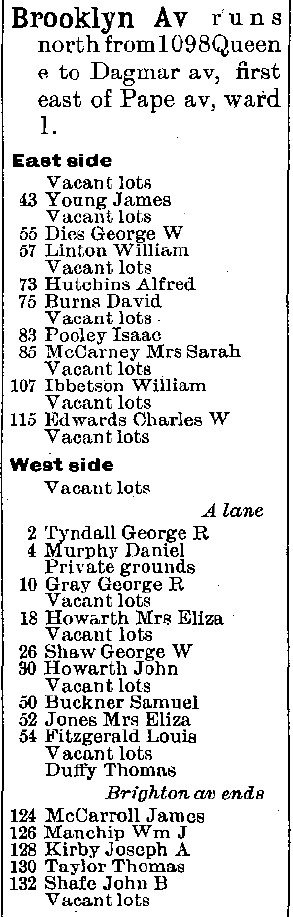

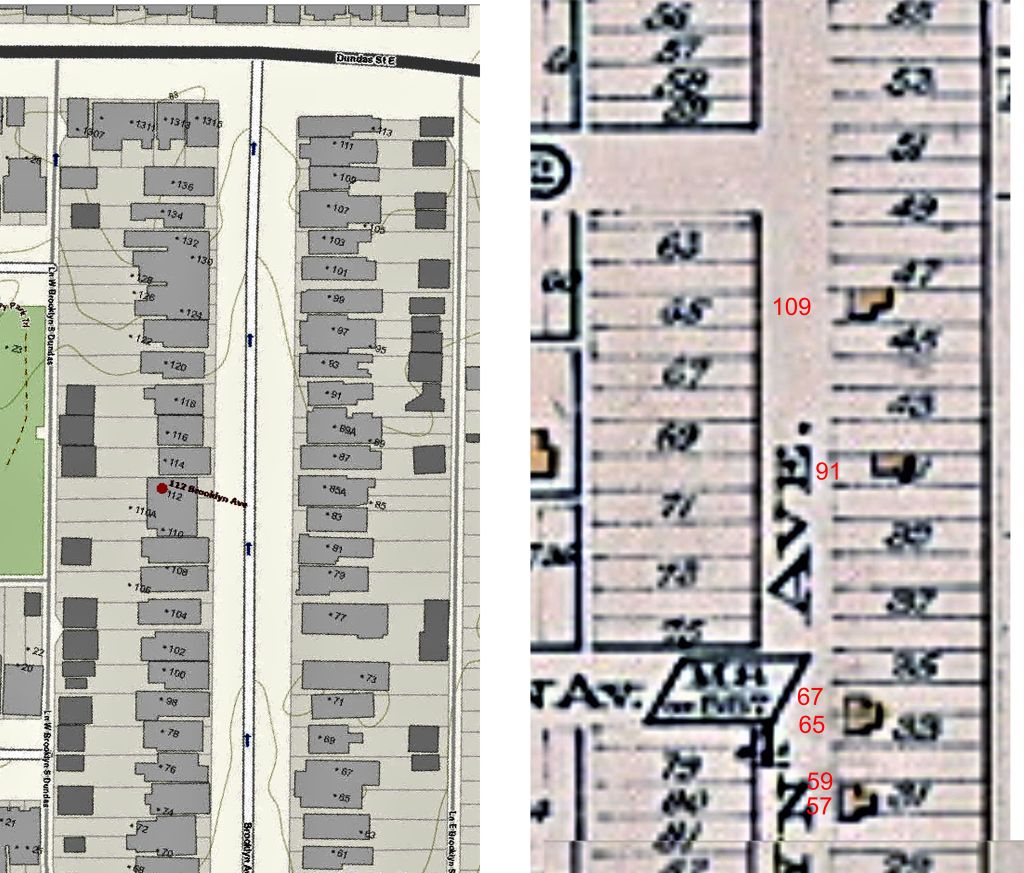

It was a challenge to sit down with a modern map and old street plans to determine exactly which are the oldest houses on the street. But when the job was done, it made total sense! These houses all stand out as distinct. They have all were built in the 1880’s.

For more about Victorian architecture in Ontario go to: http://ontarioarchitecture.com/Victorian.htm

The Heritage Resource Centre at the University of Waterloo has a guide to the architectural style in the province: https://www.therealtydeal.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Heritage-Resource-Centre-Achitectural-Styles-Guide.pdf

This article includes:

- The Oldest Houses

- Some Architectural Terms

- Some Online Resources for Maps and Plans

1. The Oldest Houses

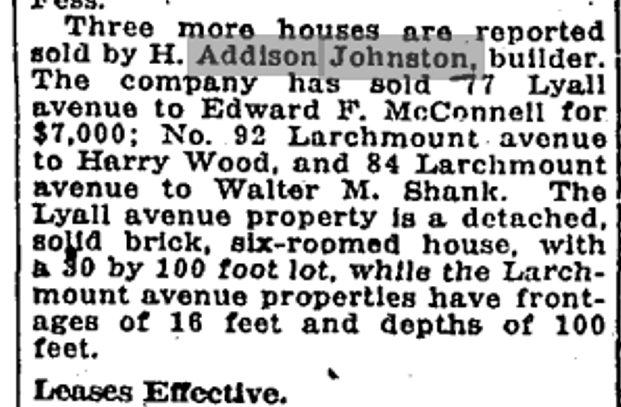

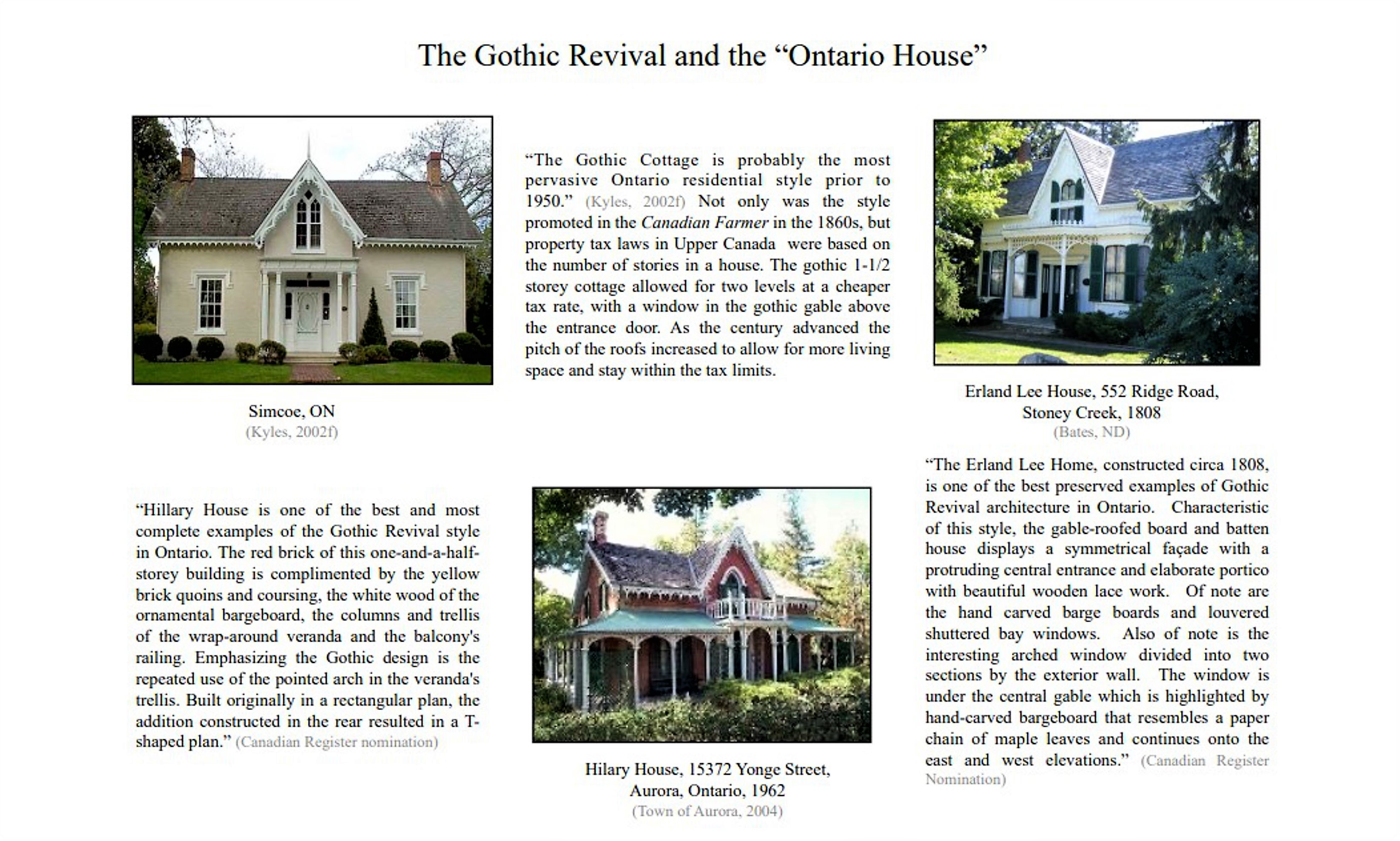

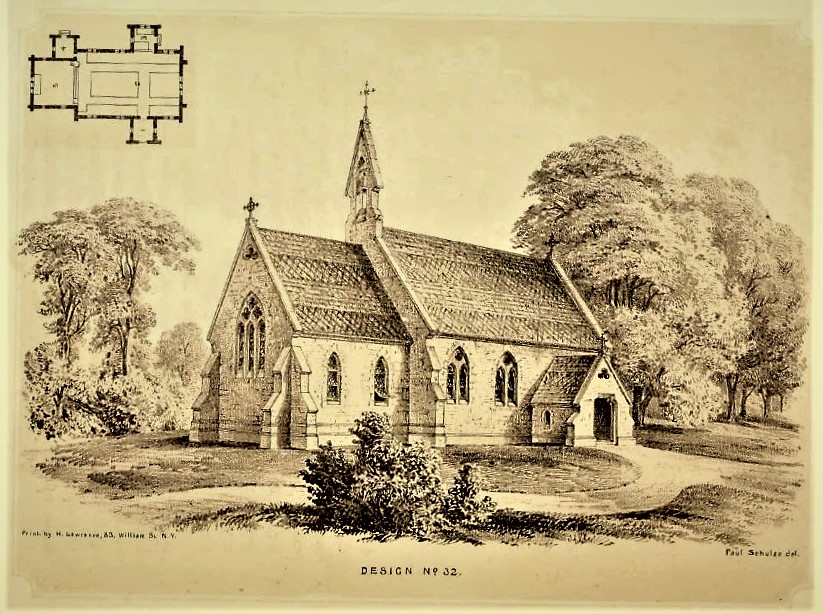

57-59 is a “double house”, no doubt built by a brickmaker as it is a masterpiece showing off fancy bricklaying — from the lozenge-shaped diapering in the gable to the subtle hood moulds over the windows and doors and the banding. It would originally have had a verandah and fancy bargeboards under the eaves. Appearances are deceiving though. Only the front has the brickwork. The sides of the house were originally clapboard or lathe and stucco. [They won’t let me take a jackhammer to the exterior walls so that I can verify the construction material. Just guessing.] It is in the Gothic Revival style and, like the other houses mentioned here was built between 1884 and 1889.

65-67 is another “double house”, but emphasizes the vertical aspect so dear to neo-Gothic architects more than 57-59. This is a bay-and-gable design similar to the one on the website here: http://ontarioarchitecture.com/Victorian.htm#Gable%20and%20Bay

Like 57-59 these narrow, two-storey houses had dirt-floor basements, a brick front and wood side and rear walls, with a summer kitchen at the back.

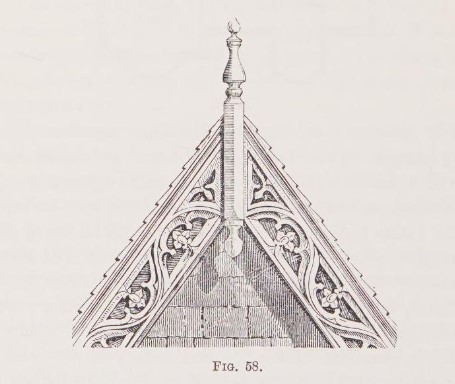

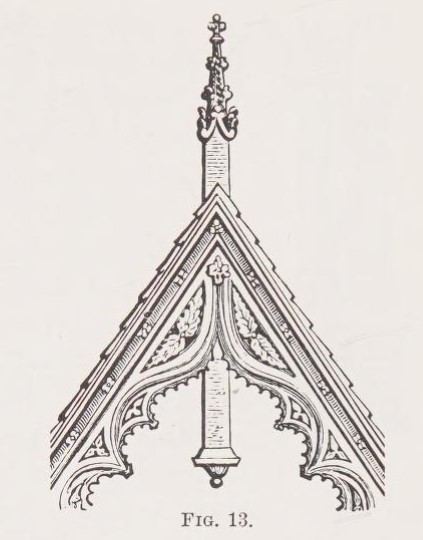

67 has the original double door which would have allowed the lady of the houses and her feminine visitors to sweep through the entrance in their hooped skirts. It also is a show home for fancy bricklaying. It has bay windows on each side, but the verandah is a later Edwardian addition. It would have had a smaller but no doubt fancier front porch. It would also it would have had fancy bargeboards under the eaves and probably a finial topping the centre gable, leading your eye up to heaven and away from the mud of the surrounding brickyards. It also would have concealed the all-important lightning rod.

All these houses speak to the Victorian love for elaboration coupled with order — they are all symmetrical. Now we usually paint the trim of these lovely old houses in subtle shades of cream, brown or white. But the late Victorians loved colour and the original paint scheme may have been eye-popping with purples, reds, blues and yellows.

Check the lancet-arch ventilators at the top. They look like tiny windows or miniature medieval cathedrals, but helped improve the air circulation in the house.

91 Brooklyn Avenue https://www.google.ca/maps/place/53+Brooklyn+Ave,+Toronto,+ON+M4M+2X4/@43.665118,-79.3371535,3a,75y,74.28h,87.65t/data=!3m7!1e1!3m5!1sW1rn_j_sW_LBYrpREhabRQ!2e0!5s20130501T000000!7i13312!8i6656!4m5!3m4!1s0x89d4cb781e6ffebf:0x61b1120f6e31940d!8m2!3d43.6639421!4d-79.3364562?hl=en

This detached house retains its beautiful, flowing bargeboards and the yellow (called white at the time) bricks at the corners of the house imitate the much more expensive stone quoins that only the rich could afford.

This Gothic or “Ontario cottage” hides its dichromatic face under paint, but probably looked very much like those at the Ontario Architecture site: http://ontarioarchitecture.com/gothicottage.htm

The Urbaneeer also has a good article on the Ontario Gothic revival cottage: http://urbaneer.com/blog/ontario_gothic_revival_cottage

2. Some Architectural Terms

Arch: Curved structure used as support over an open space or recess. The wedge-shaped elements that make up an arch keep one another in place and transform the vertical pressure of the structure above into lateral pressure.

Architecture: The art of designing and building according to the rules regulated by nature and taste.

Bargeboard: fancy, wooden ornately carved scrollwork, attached to and hanging down under the eaves of the projecting edge of a gable roof.

Bay Window: A window forming a bay or recess in a room or an alcove projecting from an outside wall and having its own windows and foundation.

Bay: A unit of interior space in a building, marked off by architectural divisions; sections of a building, usually counted by windows and doors dividing the house vertically.

Bond: the pattern in which bricks are laid, either to enhance strength or for design.

Brick: was a much more expensive cladding than plaster and lathe or wood and as a result, there were very few houses built with this material until the 1860s. Early bricks were somewhat irregular in size, averaging less than 8″ x 4″ x 2″. They had flat surfaces but were often rough, warped, and cracked. The rough cast plaster house or brick-fronted house would have been cheaper to build than an all-brick structure, while still offering some fire protection. Di-chromatic brick: red and white (yellow). Commoner as local brick production increased.

Builders: lacked formal training – there were few master builders or architects at the time.

Carpenter Gothic: ornate wood decoration; also called gingerbread, carpenter’s lace (for an example, see the house on the north side of Dundas Street directly across from Brooklyn Avenue).

Cladding: exterior surface material that provides weather protection for a building

Clapboard (weatherboard): a house siding of long, narrow boards with one edge thicker than the other, overlapped to cover the outer walls of frame structures.

Cottage: in the Victorian era this was not a get-away retreat on a Muskoka lake, but a small house. In the late 1800’s the most common form of a small house in Ontario and much of the US was the “working man’s cottage”. This loose design was influenced by British and American architects who were trying to reduce the unsanitary and crowded conditions of working-class housing. A model cottage was built at the Crystal Palace industrial exhibition in London in 1851, giving momentum to its appearance in construction pattern books and magazines (e.g. The Canadian Farmer in 1865) that were used all over North America and Britain.

Innovations included water, internal sanitation, fresh air, and separate bedrooms for children – although sanitation was treated as an option in many cases. The style applied to the cottage was influenced by its location. In Ontario, with many immigrants from Britain, the style leaned to Gothic, with details such as finials, bargeboards (gingerbread), and window trim carrying the Gothic elements.

A variation of this home is the “Side Hall Plan” cottage, defined by having the front door to the right or left of the façade’s center

Course: a continuous horizontal row of brick or stone in a wall.

Decorative wooden trim: Most homes include a street-facing gable decorated with wood trim such as brackets, patterned millwork, bargeboards, or shingling; this decoration is also occasionally used on the porch gable.

Diaper: A pattern formed by small, repeated geometrical motifs set adjacent to one another, used to decorate stone surfaces in architecture.

Doors and windows: Front facades of homes in this district are typically narrow, which means that architectural elements like windows and doors take up a large proportion of space.

Ell: an addition or wing to a house that shapes it like an “L” or a “T”.

Facade: the faces of a building, often identified by the cardinal direction (N,S,E,W) which it faces.

Finial: An ornament at the tip of a pinnacle, spire or other tapering vertical architectural element.

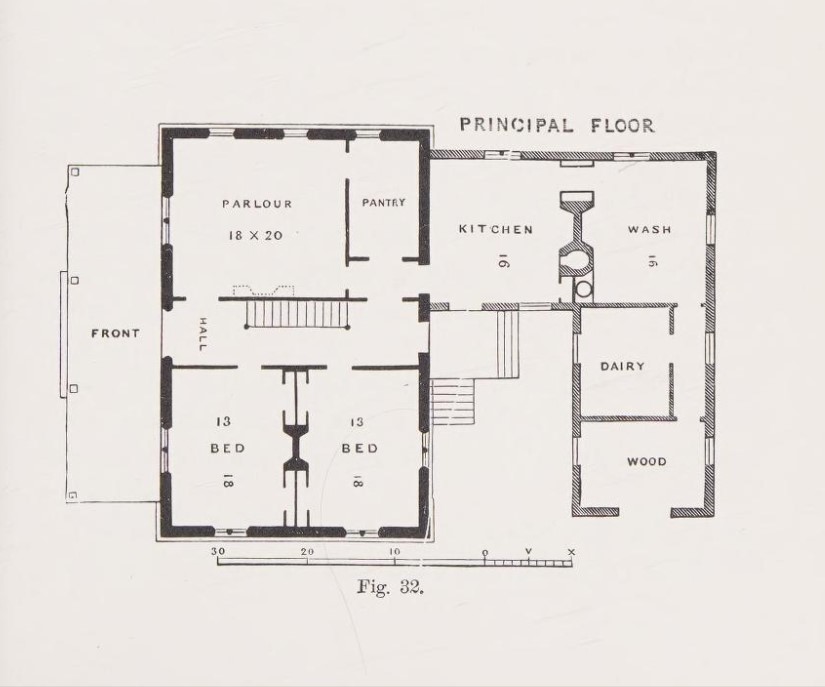

Floor plan or ground plan: Horizontal cross-section of a building as the building would look at ground level. A ground plan shows the basic outlined shape of a building and, usually, the outlines of other interior and exterior features. The main floor and upper floor plans (if any) are always included. In addition, depending upon the scope of the survey, plans at the following levels may be required: foundation plan, reflected ceiling plans (crawl space, main and upper floors), attic joist plan, rafter plan, and roof plan.

Foundation wall, beam, column, footing: Many houses were placed directly on the ground. These deteriorated if they were not raised above the soil. Sometimes houses were set on mud sills on the ground. Masonry walls (bricks and mortar) were used for footings from c. 1850 – 1900. Poured concrete foundations became popular in the late 19th century. Houses on brick foundations tend to settle over the years and are prone to moisture in the basements.

Gable: (1) that part of the wall, triangular in shape, defined by the sloping sides of a double pitch or gable roof; (2) the end wall of a building.

Glazing: the glass in a window. Glazing was expensive and it is very likely that all of the houses in this article had shutters to protect the glass.

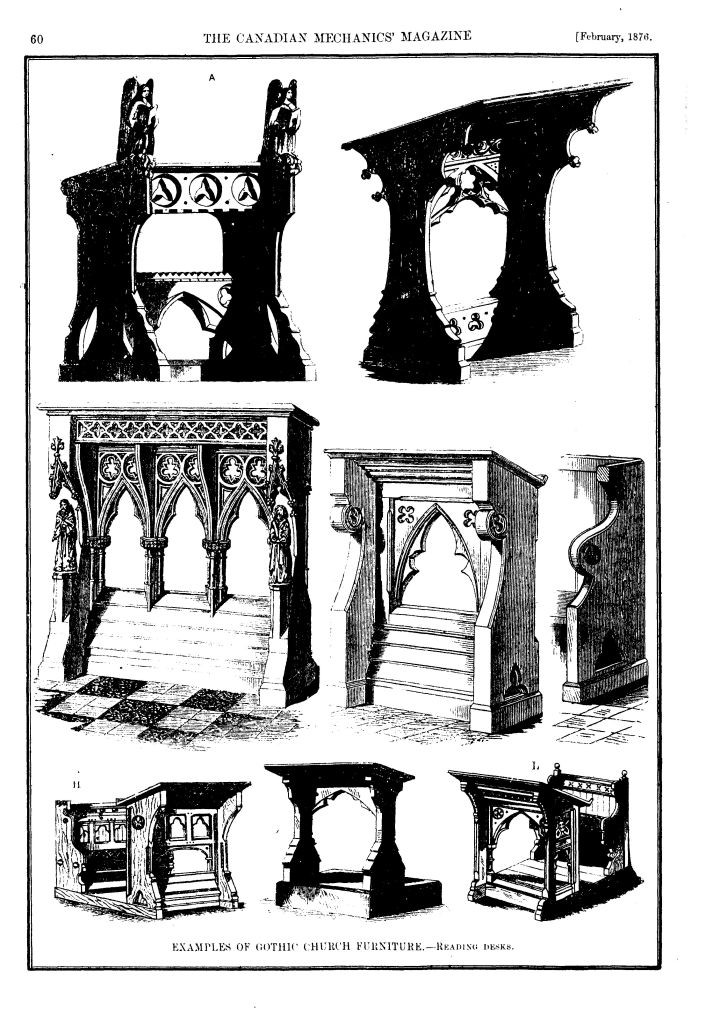

Gothic Revival 1845-1890: The Gothic Revival style first appeared in England in the late 1700’s. Around 1840, shortly after Queen Victoria’s accession to the throne, the Gothic Revival in Britain became very popular. The Victorians who saw it as a way to recapture both medieval romance and a sense of national relevance. Three forms were revived: Early English-squat high steeped with masonry cladding and pointed single light windows; middle pointed, featuring windows of a curvilinear design; and attenuated Perpendicular, marked by slender spires, elongated pinnacles, and crenellations. Late high Victorian Gothic homes usually featured two colours of brick, usually red with yellow for decoration (dichromatic brick) and heavier ornamentation especially bargeboard. Much of Toronto’s cheap housing of the 19th century was built in a simplified Gothic style, and faced with wood lathes and stucco or even mud.

Head: the top of the frame of a window or door.

Header: the end of the brick seen in a brick course.

Lancet: A slender, pointed window.

Leaded glass: small panes of glass held in place with lead strips; glass may be clear or colored (stained).

Light: small panes of window set into an individual sash.

Lime mortar: lime + sand + water; used prior to the late 19th century to lay brick and stone, and for parging exterior masonry walls.

Lintel: A flat horizontal beam that spans the space between two supports.

Lozenge: A diamond shape.

Mortar: a material used in the plastic state and troweled into place to harden, used to consolidate brick, stone, and concrete blockwork.

Mullion: The vertical element that separates the lancets of a window.

Muntin: the thin vertical bars that vertically divide a window or other opening into small lights.

Ontario Cottage: These one-story homes typically built between the 1830s and 1880s include gingerbread trim and formal symmetry on the front façade, an entry door centered to align with the steep-sloped, gable or hip roof designs, and a peaked central gable dormer. This style featured a central gable with windows flanking a central doorway.

Pitch: the degree of slope of a roof, usually given in the form of a ratio, such as 6:12.

Porch: a roofed exterior space on the outside of a building.

Quoins: rectangles of stone or wood used to accentuate and decorate the corner of a building.

Rafter: a framing member supporting the roof.

Repointing: removal of old mortar from joints of masonry construction and filling in with new mortar.

Sill: the horizontal water-shedding element at the bottom of a window or door frame.

Stained glass windows and transoms: Stained glass decoration is sometimes found used in homes, especially in large, arched windows in the front of the house, and in transoms over the front doors.

Stretcher: the long side of a brick when laid horizontally.

Stringcourse: A continuous projecting horizontal band set on the surface of a wall and usually molded.

Stucco or roughcast The earliest homes were constructed quickly with the easiest and most available materialsr. Lake stone, river stone and glacial erratics picked up from farm fields were used for the cellar walls and footings. Stucco or roughcast was common up to the 1850’s and even after as housing for the poor. Roughcast plaster was laid over wooden laths. The finishing coat was a thick mixture of thin mortar and small pebbles, thrown or “cast” against the wall. Lumber was plentiful. The narrow boards turned out from the mills were not esteemed for export so the narrowest, about six inches in width, were made use of. These were placed on the foundation timbers and securely nailed, one on top of another, the edges of alternate boards projecting so as to form a groove into which the mortar was pressed. Early stucco used animal hair (often horse), straw, or other binders. Sand or fine gravel was used to create texture.

Studs: the upright framing members for a wall.

Trim: the framing of features on a façade which may be of a different color, material, or design than the adjacent wall surface.

Two-story Victorian houses with side entry: Another vernacular house type that appeared in the Victorian period is the two-story house with side entry. They use a variety of Victorian treatments on the narrow, front facades which face the street.

Verandahs: Verandahs and porches provided shade for the home and offered a sheltered place to sit, especially during warm summer evenings. They also gave homeowners a place to observe and interact with their neighbours. Porches were initially made of wood, which could warp, leak or rot if improperly constructed. By the 1910s, porches were constructed from concrete and brick. As the world became less rural, demand for porches declined; cars stirred up dust and people became more private, spending their spare time indoors with their families and televisions. Most pre-1914 homes in this district were designed to have some sort of covering for the front door entrance, whether it is a front porch, verandah, or a small overhang called an “over door”. Homes built during the 1920’s feature porches that are integrated into the roofline. Porches include a variety of features, including columns, spindles, and handrails.

Verge board: see bargeboard.

Vernacular: used to describe buildings with little or no stylistic pretension, or those which may reflect a rural interpretation of high-style architecture of the day.

Water table: a slight projection of the lower masonry or brick wall a few feet above the ground as protection against rain.

Windows: glass set into a sash, or frame double-hung — a window with two sashes, one above the other, arranged to slide vertically past each other. Casement: a window with the sash hung vertically and opening inward or outward. Components of windows included frames, sash, muntins, heads, hood mouldings, decorated jambs, mouldings, exterior shutters.

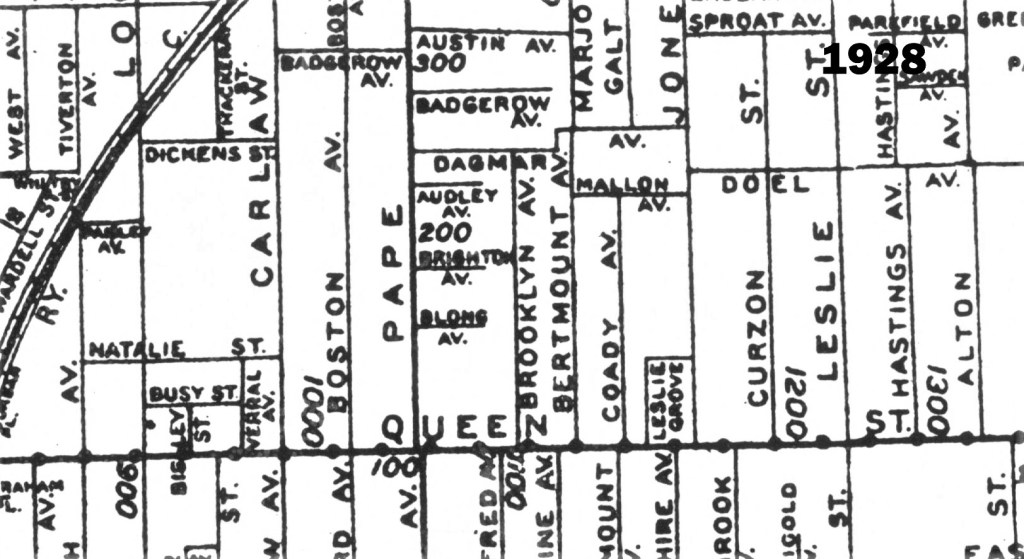

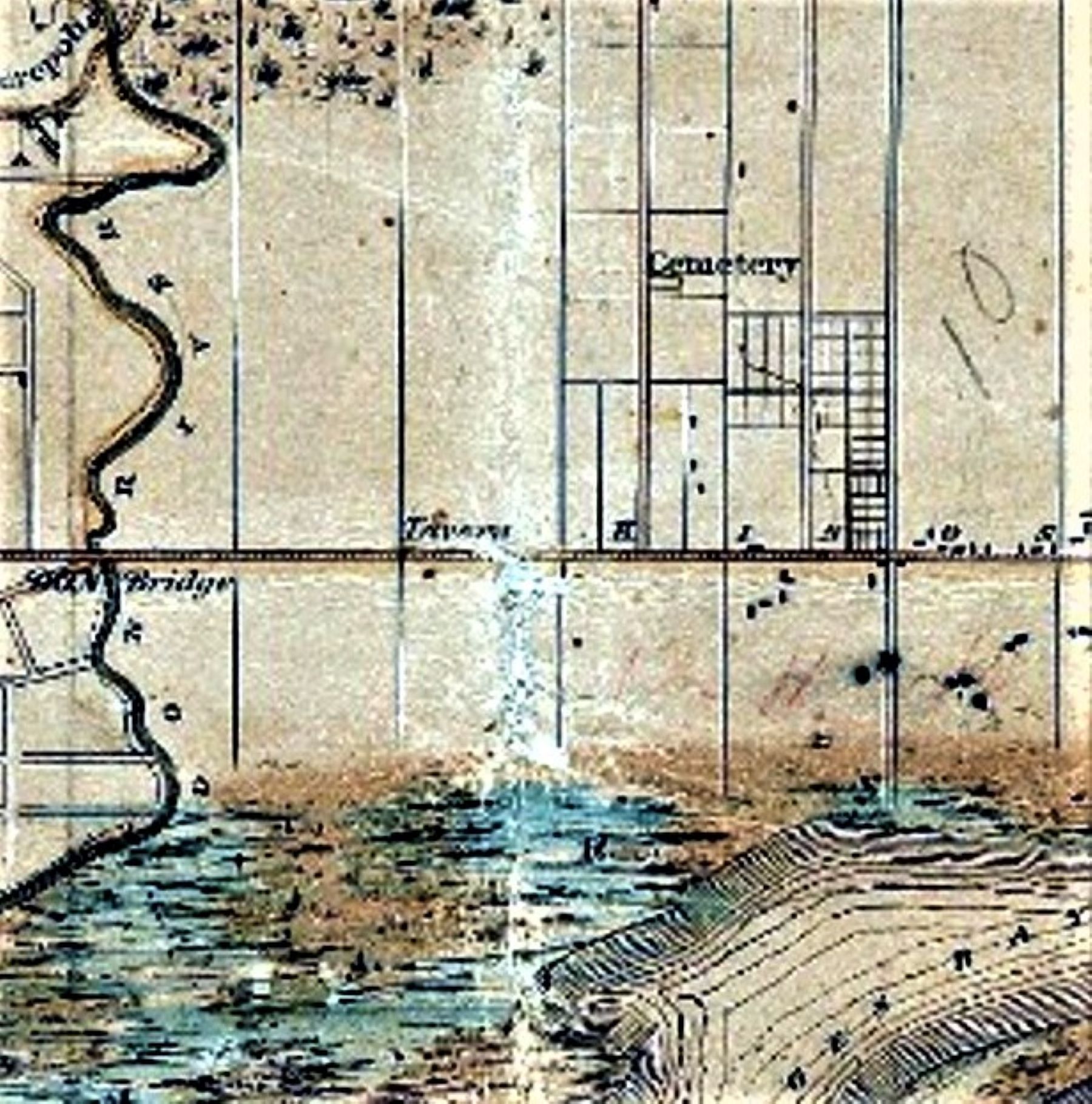

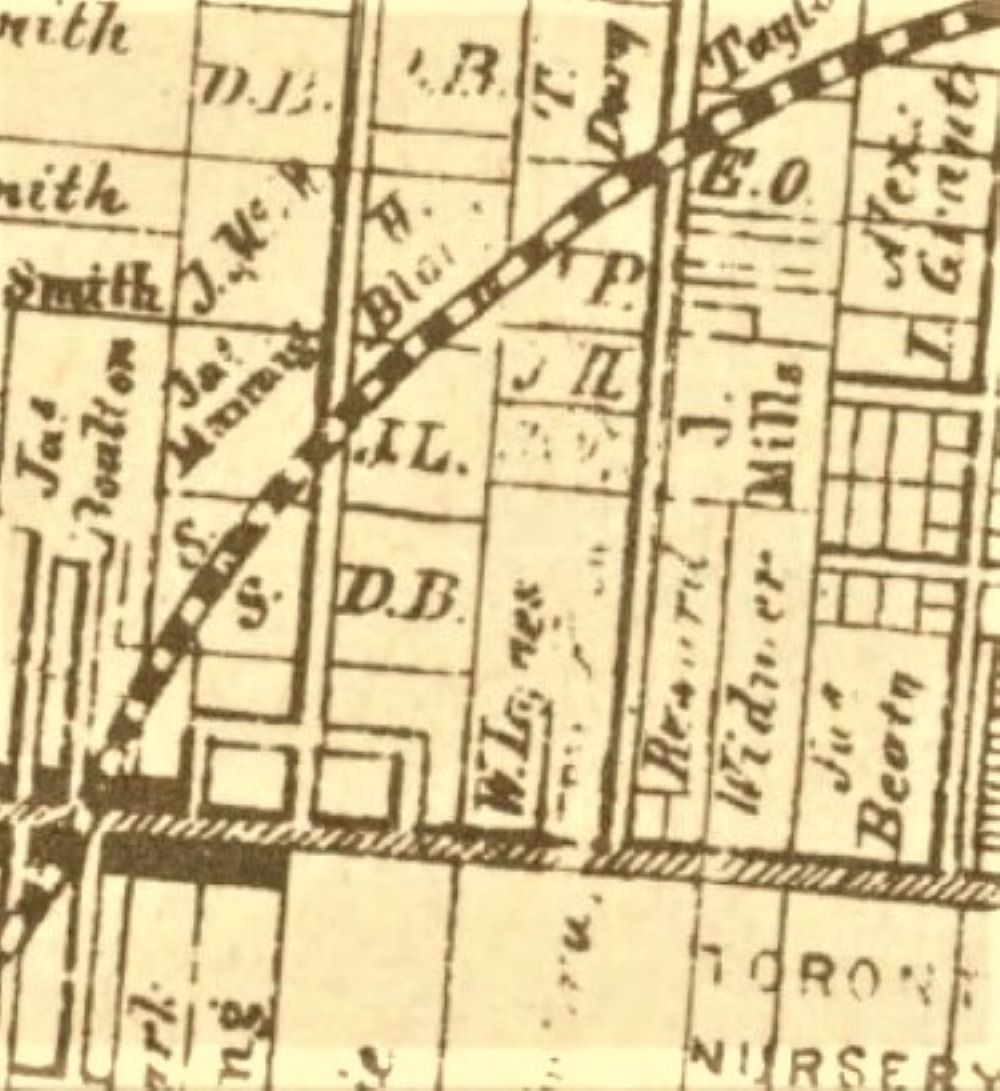

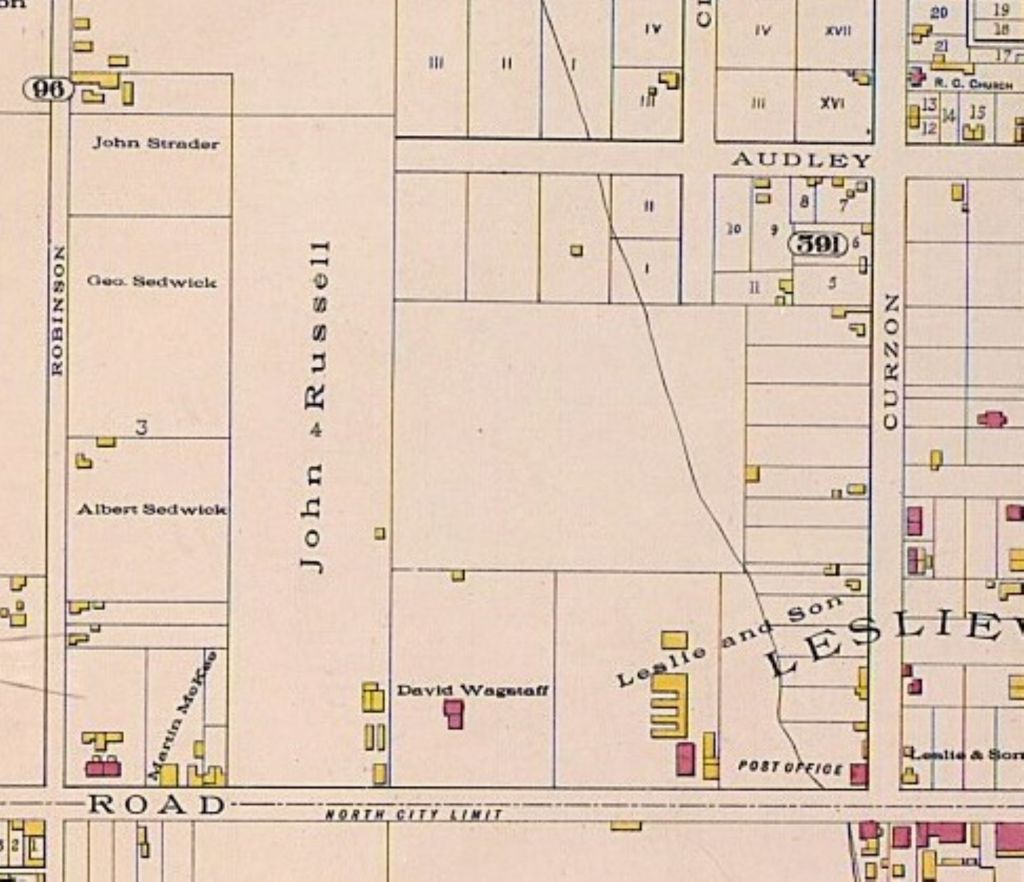

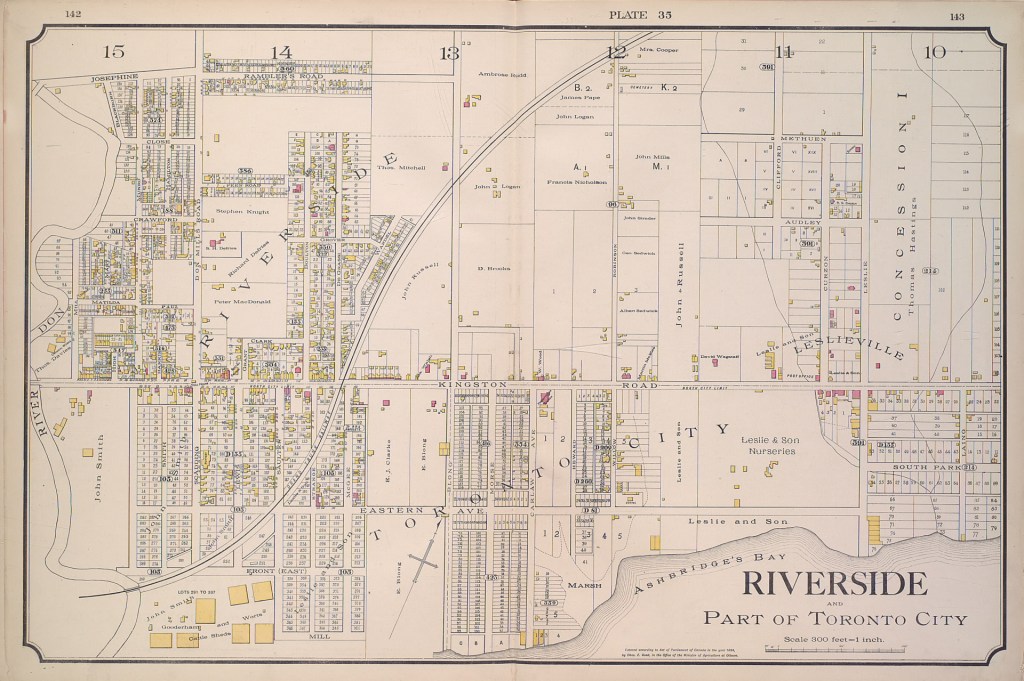

3. Some Online Resources for Maps and Plans

To see more Goad Atlas plans go to: http://goadstoronto.blogspot.com/

For more early maps of Toronto go to: http://oldtorontomaps.blogspot.com/

For an excellent City of Toronto map go to: https://map.toronto.ca/maps/map.jsp?app=TorontoMaps_v2