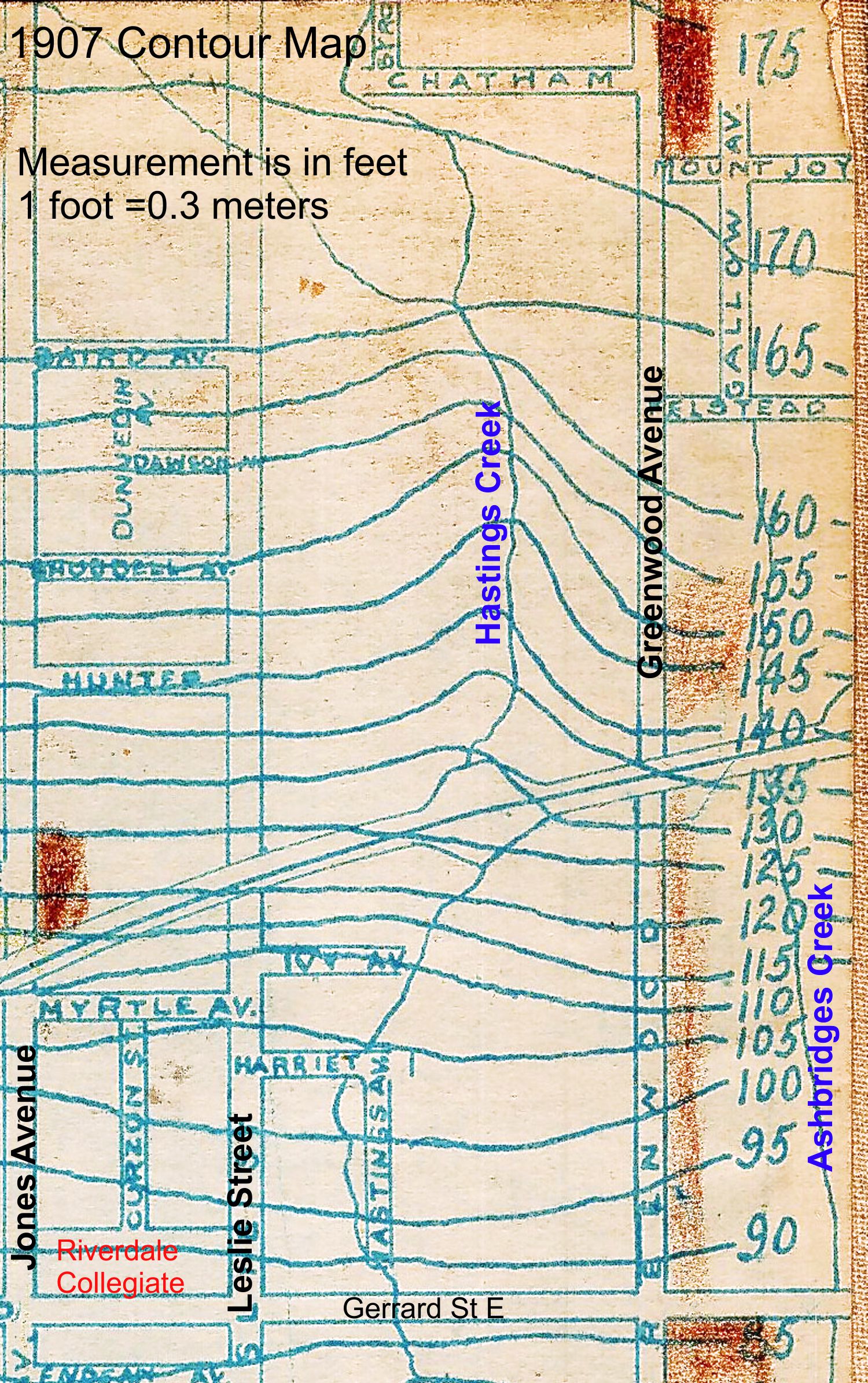

London, England has a BBC show, The Secret History of Our Streets. The series claims to explore “the history of archetypal streets in Britain, which reveal the story of a nation.” Our streets are just as interesting and our stories goes back millennia before Austin Avenue existed to when Leslie Creek was full of salmon and Anishnaabe, Haudenosaunee and Wendat gathered wild rice in Ashbridge’s Bay. I hope you enjoy this page. My research ends in 1919, a century ago. I have not explored the history of every family, Austin Avenue has more secrets to tell.

Here are some of those stories — those from 2 to 17 Austin Avenue

2 Austin Avenue

Walter Gray was born on November 9, 1857 in at Gray’s Mills, York Township, now part of the Donalda Golf and Country Club. He married Annie Emma Clifford on January 30, 1884 and they had five children in 11 years. The Grays had a grocery store at 2 Austin Avenue and lived above the store. They moved to 100 Boulton Avenue about ten years later.

His wife Annie Emma passed away on July 29, 1916, on Bolton Avenue, at the age of 49. They had been married 32 years. Walter Gray died on April 8, 1938, in Dunnville, Ontario, at the age of 80.

Son William John was born on December 19, 1885, in Toronto, Ontario. He Gray married Annie Mary Norris on June 28, 1907, in Toronto. They had two children during their marriage. He died in 1948 at the age of 63, and was buried near his parents. Annie Mary Norris died in 1960 and was laid to rest next to her husband. The Gray family plot is in Saint Johns Norway Cemetery and Crematorium, Woodbine Avenue.

Ironically both the Gray family homestead and Leslie Street School principal Thomas Hogarth’s house have been honoured with historical plaques.

4 Austin Avenue

4 Austin Avenue was the home of Henry Bowins in 1919 and, in 1921, by widow, Mrs. Louisa (Beckett) Greenslade and her five children, ranging in age from 7 to 17. in 1921. Her husband, William Henry Greenslade, a market gardener, had dropped dead of a heart attack in 1915. The family lived in Etobicoke at that time.

6 Austin Avenue

8 Austin Avenue

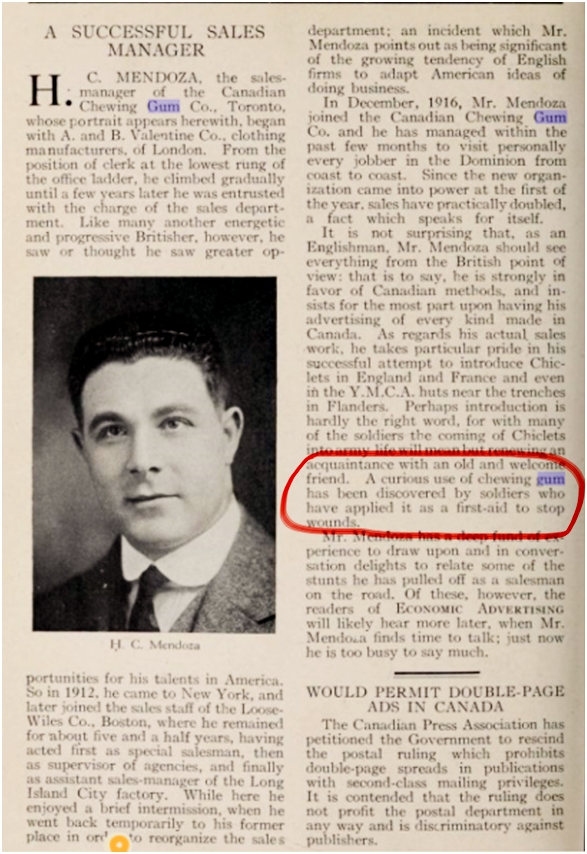

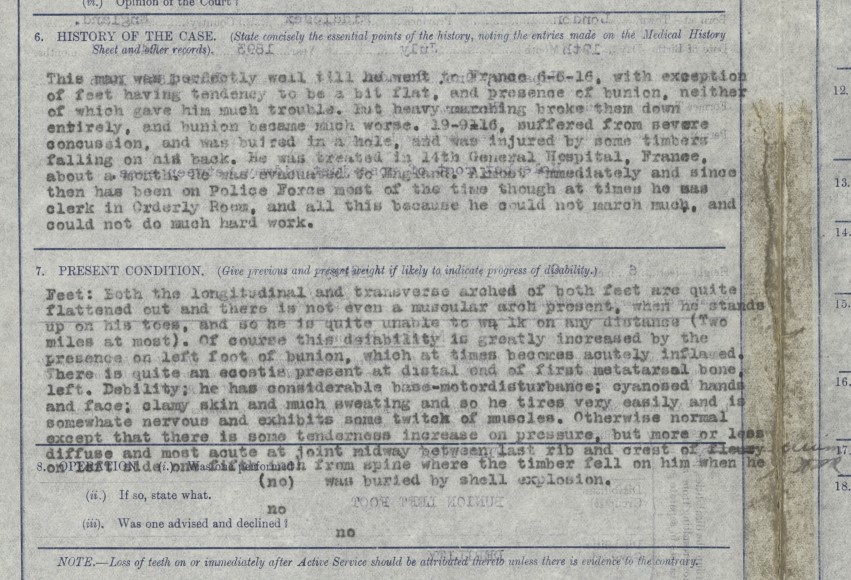

John Christopher Waldron married William Robertson Hodge’s sister Eveleen in 1919 and was lived with her, sister Jean, and their mother, Mary. Like his brother in law he was a tall man for the time (5’11”) and fit. He was an Irish Catholic while Eveleen Hodge was an Irish Protestant. Both were from Dublin. Unlike his brother-in-law, he was not conscripted but volunteered. Like his brother-in-law he was hit by shellfire. Clearly from the medical records doctors had a hard time identifying just what was wrong with Pte. Waldron, apart from flat feet which was easy. The blast buried Waldron completely under mud, timbers and rubble, causing a severe concussion and what was known as “shell shock “. He died in 1964.

10 Austin Avenue

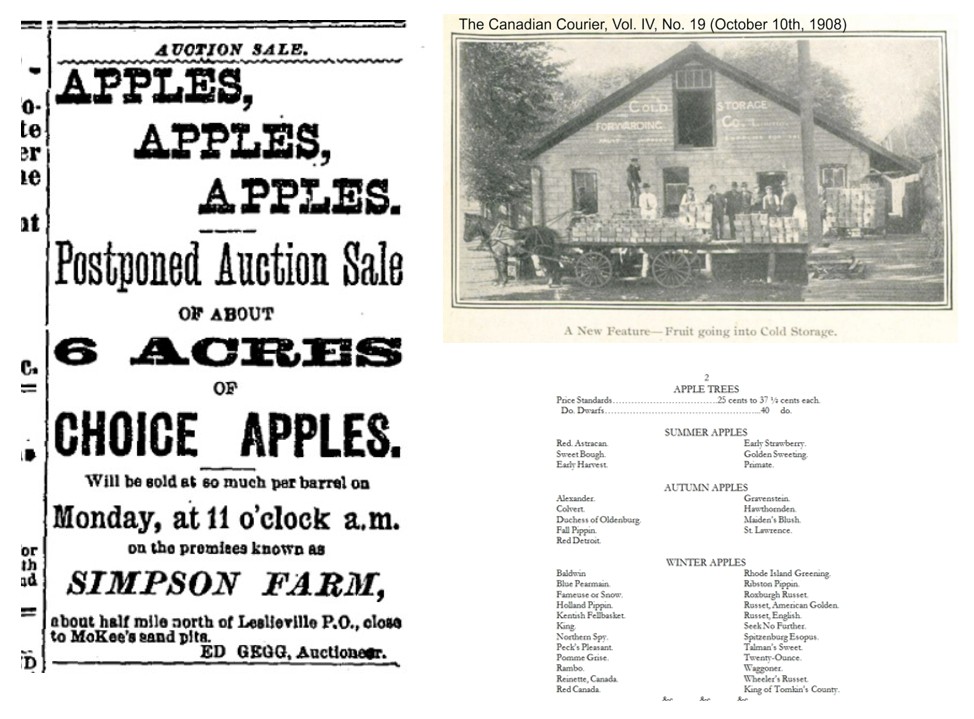

It appears that Mrs. Robinson at 10 Austin Avenue took in lodgers, as many widows did. Since the lodgers were mostly young men who moved frequently, it is difficult to determine just which Frank Mulhern was responsible, but it appears to have been Frank Beauchamp Mulheron (1881-1917) who moved to the U.S. permanently shortly after this assault occurred. Strong-arm tactics to hijack valuable cargo was not uncommon though this was particularly audacious. Often the motive was to re-sell the produce and sometimes simply to get something to eat. The perpetrators usually knew their victims and counted on intimidation to keep the victims from reporting to the police. Gangs were a reality back then too. Timothy Lynch of 51 Austin Avenue took the law into his own hands shooting those who robbed his orchard. But that’s another story.

Dudley Seymour Robinson was born on July 6, 1892, in San Jose, California, USA,. Both his parents were English. He married Gladys Elsie Moffat on October 6, 1920, in Toronto. They had two children during their marriage. He died in March 1963 in Michigan, USA, at the age of 70. In 1911 he was living with his widowed mother Rosina Alice Robinson at 10 Austin Avenue and working as a Foreman in a leather shop. Dudley Seymour Robinson enlisted on February 16, 1916 and sailed to England where he became an Acting Sergeant but injured his left knee while training. A torn meniscus kept out of the trenches, he was discharged from the army on Dec. 17, 1916 and sailed on the troop ship Metagama back to Canada, arriving in St. John, New Brunswick on Christmas Day 1916. He married Gladys Elsie Moffat in Toronto, Ontario, on October 6, 1920, when he was 28 years old and they lived in an apartment on Silverbirch Avenue. His mother Rosina Alice passed away at home 10 Austin Avenue on November 9, 1922, at the age of 55 from pneumonia. After his mother’s death Dudley Robinson moved to Detroit and died at the age of 70 in March 1963 in Michigan, USA.

14 Austin Avenue

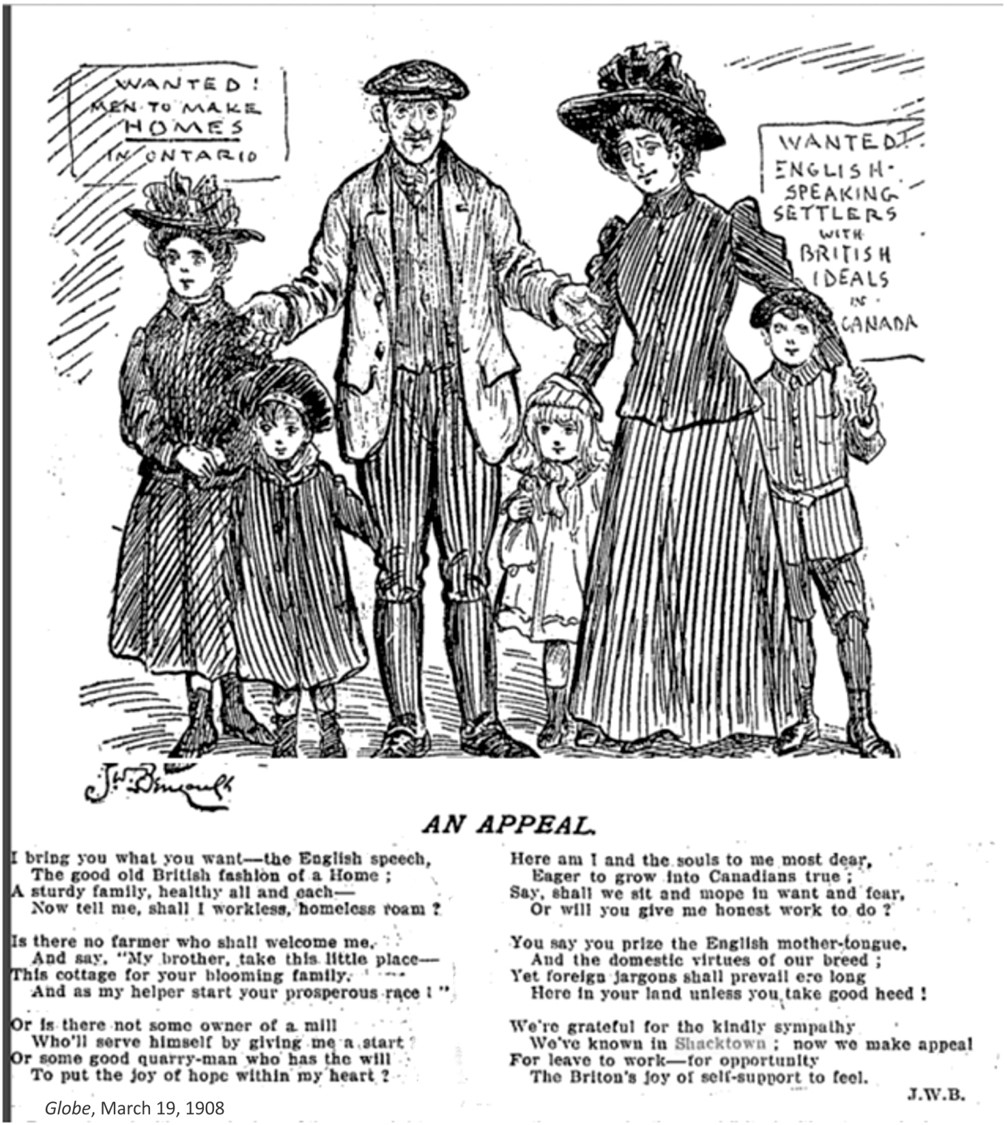

William Edward Harrold was born in March 1873 in Monkton Combe, Somerset, England, his father, William, a wheelwright, was 54 and his mother, Amelia Ann, was 29. Though in 1871 the family owned their own home and even had a servant, Ten years later family was destitute and he was educated in a pauper school. In 1881 his father was in the Poor House as a pauper, as was William and his brothers, Alfred and Henry, but there was no sign of his mother. His father died in 1887. In 1890, at the age of 17, he immigrated alone to Canada. He was related to the Billing family, another Somerset family, for whom Billings Avenue is named. William Harrold married Ellen Sophia Eva Cox on June 15, 1897, in Toronto, Ontario. They had two children during their marriage: Alfred William Badgerow Harrold and John E Harrold. He died at home 14 Austin Avenue on November 11, 1936 of heart disease. Though he spent his working life in a foundry, his death certificate lists his true vocation: musician.

The Wheelwright’s Arms pub in Monkton Comb, now part of the City of Bath, was likely the family home of the Harrolds. To see photos of the pub go to: https://the-wheelwrights-arms-gb.book.direct/en-us/photos

17 Austin Avenue

Every family has stories and secrets. We don’t know why 17-year-old Kate Wellings mysteriously left home, alarming her parents. But perhaps the numerous articles about the Wellings family might hold a clue. My sympathies are with Kate. I was a teenage daughter of a man with some “unique” ideas, obsessed with politics and who wrote numerous Letters to the Editor. I was sometimes proud of him and sometimes embarrassed. Perhaps Kate felt the same or perhaps there was another reason.

The Wellings family were the first to live at 17 Austin Avenue and built the house there where Katherine “Kate” Wellings was born on January 31, 1887, but their story, like every family’s, goes back further.

Father George Washington Wellings was born in 1855 in Birmingham, England, the centre of Britain’s steel industry. His grandfather had been a blacksmith. His father, George Wellings Sr., was a “steel toy maker”. However, at the time, “toys” were not the playthings we think of today, but the term meant small metal items like buttons and buckles, and was part of the jewelry trade.

In 1830 Thomas Gill described the production of steel jewelry in Birmingham, from cutting the blanks for the steel beads or studs, to final polishing in a mixture of lead and tin oxide with proof spirit on the palms of women’s hands, to achieve their full brilliance. Gill comments: No effectual substitute for the soft skin which is only to be found upon the delicate hands of women, has hitherto been met with.” — from Revolutionary Players Making the Modern World, published by West Midlands History at https://www.revolutionaryplayers.org.uk/birmingham-toys-cut-steel/

George Sr. also worked as a gun maker during the 1850’s and 1860’s. This was a lucrative business during that period. Between 1855 and 1861, Birmingham made six million arms most went to the USA to arm both sides in the American Civil War. Not long after George Wellings Sr. father retired from gun making and opened a pub, The Wellington, in the Duddeston at 78 Pritchett Street. German aircraft bombed the area heavily in World War. The pub no longer remains.

For more about Birmingham’s gun making history go to: http://www.bbc.co.uk/birmingham/content/articles/2009/02/18/birmingham_gun_trade_feature.shtml

George Jr. became a jeweller specializing in engraving on gold.

George Washington Wellings married Anna Maria Johnson in 1875 in Birmingham. They and their five children immigrated to Toronto in 1884. They would have seven more children, all born in Toronto.

Walter was their first child born in Canada – at home 13 Munro Street. Dr. Emily Stowe delivered the baby. Florence was born at home 17 Austin Avenue in 1889 and was soon joined by sister Hilda Marie was born on October 4, 1891. Harold was born on July 14, 1893. Another son Howard George was born on January 1, 1896, but died two years later on March 21, 1898. Irene Wellings was born on September 18, 1897.

In 1896 George Wellings ran for Alderman for the first time and was beaten badly by brick manufacturer John Russell.

Wellings a proponent of the ideas of Henry George, popular at the time, but still on the fringes. For more about the Henry George Club, go to:

http://www.dollarsandsense.org/archives/2006/0306gluckman.html

or

http://henrygeorgethestandard.org/volume-1-february-26-1887/

A tireless activist, George Wellings persevered. In the days before social media, Letters to the Editor had to fill the need for expressing political ideas.

Unsuccessful in his attempt to enter municipal politics as an Alderman, in business George Wellings prospered, renovating his home at 17 Austin Ave and building a new factory downtown on the site of his previous manufacturing plant.

Katherine “Kate” Wellings married Albert Edward Ward in Toronto, Ontario, on November 13, 1911, when she was 24 years old.

Wellings Manufacturing Company continued to proper, turning out buttons, badges, etc., what were known as “toys” in Birmingham in the mid-nineteenth century. Many thousands of Wellings cap badges, buttons and medals went overseas on the uniforms of Canadian soldiers during World War One.

Kate’s husband died of a heart attack on January 8, 1927 at their farm on the 3rd Line West, Chinguacousy, Peel, Ontario.

George Washington Wellings passed away on May 31, 1930, in Toronto, Ontario, at the age of 75. Though he tried and tried again, he never succeeded in becoming a Toronto alderman.

Katherine Wellings married James Templeman in York, Ontario, on March 27, 1937, when she was 50 years old. Both were widowed. Katherine was living at 17 Austin Avenue at the time of her marriage. James Templeman was a truck driver from Todmorden Mills. Her mother Ann Maria passed away on April 12, 1938 at her son-in-law’s home on Oakdene Crescent. Kate Wellings died in 1960 when she was 73 years old. She is buried in Mount Pleasant Cemetery. 67 Richmond Street East is now a Domino’s Pizza take-out.

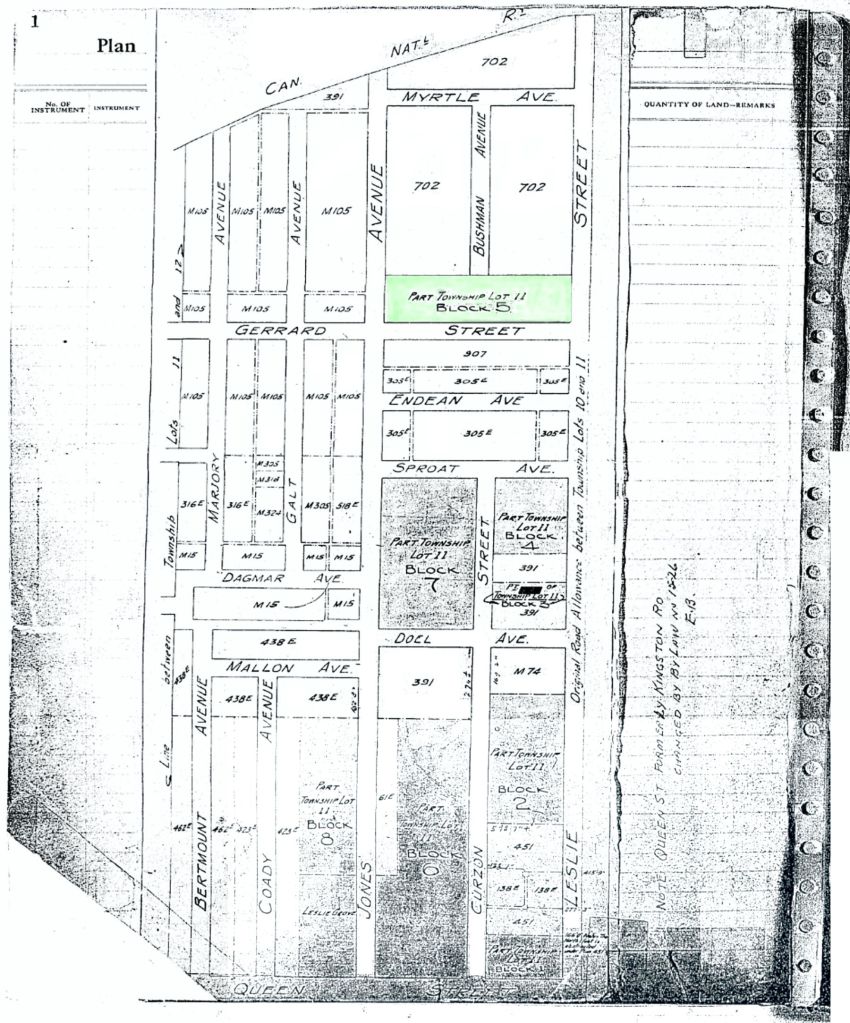

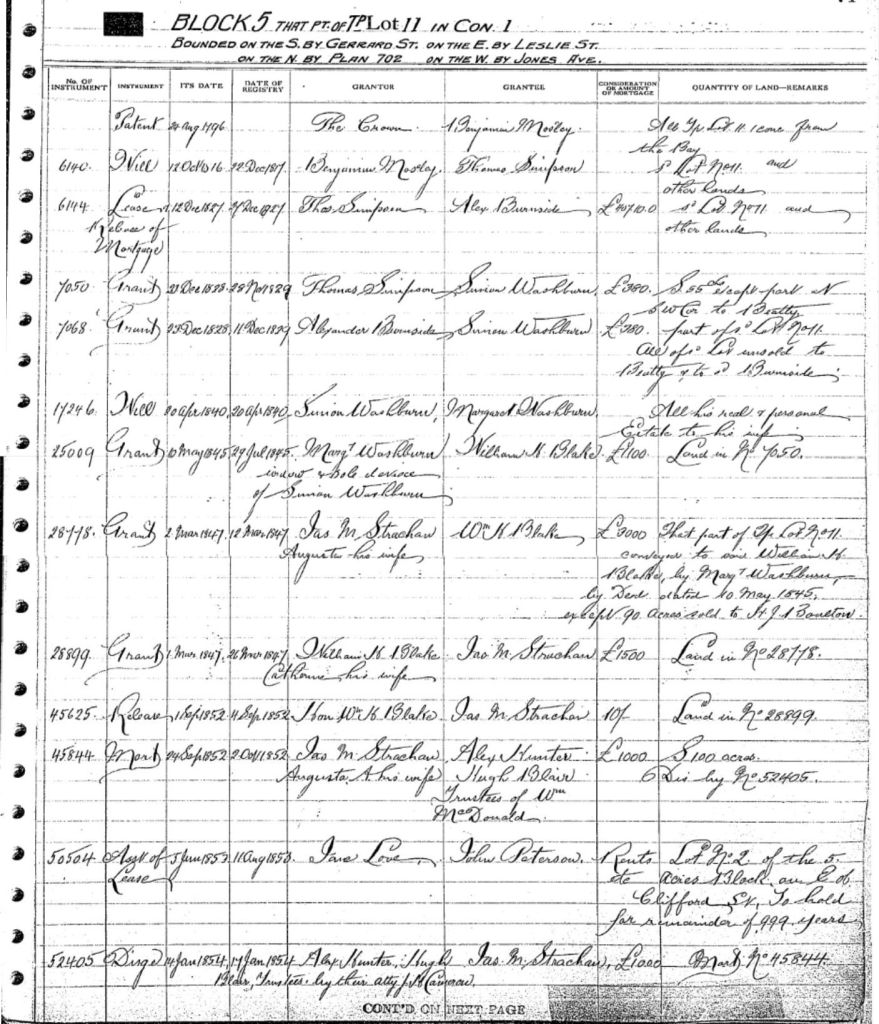

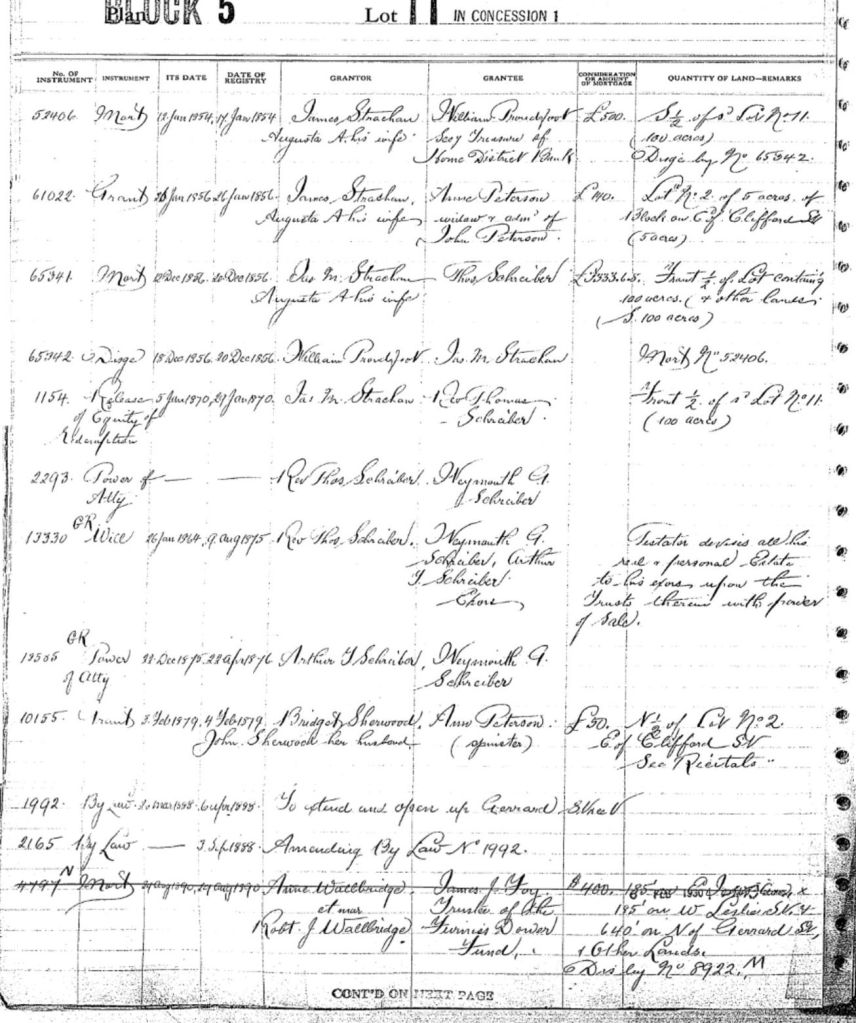

To see all of this large table drag the bar below across. The table shows who lived where and when on this part Austin Avenue from 1887 when the street was born to 1921. The 1888 City Directory was based on 1887 date and there were no street numbers as it did not get mail delivery. Postal service required numbers. Joanne Doucette

| 1888 City Directory | Lot # Subdivision 549 | # | 1889 Directory | 1890 Tax Assessment Roll Occupier | 1890 Tax Assessment Roll Owner | 1890 Directory | 1891 Directory | 1894 Directory | 1895 Directory | 1900 Directory | 1903 Directory | 1904 Directory | 1905 Directory | 1906 Directory | 1907 Directory | 1912 Directory | 1919 Directory | 1921 Directory | 1921 Census |

| North | |||||||||||||||||||

| Vacant lots | 3 frontage on Pape | 2 | Vacant lots | Gray Walter, grocer | Gray Walter, grocer | Gray Walter, grocer | Gray Walter, grocer | Gray Walter, grocer | Hannigan & Gunn, grocers | Best Wilbert E | Wells George A, Hardware | ||||||||

| Vacant lots | 3 | 4 | Vacant lots | Lowman Charles | Lowman Charles E | Lowman Edwin C | Pettit John E | Pettit John E | Pettit John E | Pettit John E | Burkholder Albert/Pettit John E | King Samuel | Bowins Henry | Greenslade Louisa Mrs | Greenslade Louisa | ||||

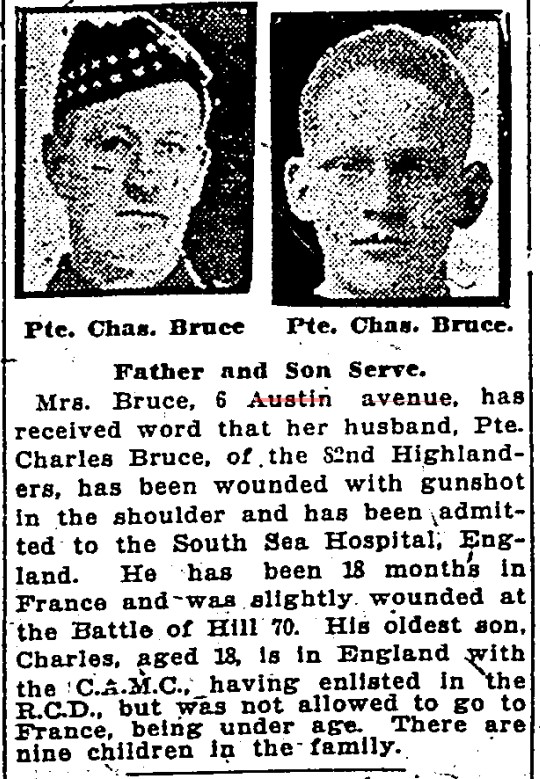

| Vacant lots | 3 | 6 | Vacant lots | Perkins Charles E | Fortier William J | Overdale Christian S | Overdale Christian S | Overlade Pauline Mrs | Overlade Pauline Mrs | Mundy William | Mundy William | Vacant | Bruce Charles | Bruce Charles | Bruce Charles | ||||

| Vacant lots | 3 | 8 | Vacant lots | Field Emma G | Farmery Charles | Booth Albert | Booth Albert | Booth Albert | Halliburton James | Pettit William H | Pettit William H | Brittain Rev David | Hodge Mary Mrs | Hodge Mary Mrs | Hodge Mary | ||||

| Vacant lots | 3 | 10 | Vacant lots | Vacant | Cosgrove John J | Mulheron Mrs Sarah | Turner Joseph | Robinson Frederick | Robinson Frederick | Robinson Frederick | Robinson Frederick | Robinson Rose Mrs | Robinson Rose Mrs | Robinson Rose Mrs | Robinson Rose | ||||

| White Henry | 3 | 12 | White Henry | White Henry | White Henry | White Henry | Jarrett George | Doxsee George W | Vacant | Crawford Walter L | Crawford Walter L | Crawford Walter L | Montgomery Norman H | Montgomery Norman H | Montgomery Norman H | Nicholson John | Macdonald Wm | Ireland Louis | Ireland Lewis |

| Vacant lots | 3 | 14 | Vacant lots | Private Grounds | Vacant | Kordell George H | Liley Henry | Taggart Thomas R | Montgomery Norman H | Stewart William H | Stewart William H | Stewart William H | Harrold William E | Harrold William E | Harrold William E | William Harrold | |||

| Vacant lots | 3 | 16 | Vacant lots | Private Grounds | Vacant | Stewart William | Simmonds Alfred | Simmonds Alfred | Murphy John | Ridley Joseph | Ridley Joseph | Ridley Joseph | Ridley Joseph | Ridley Mark | Ridley Joseph | Ridley Joseph | |||

| LANE | A LANE | ||||||||||||||||||

| South | |||||||||||||||||||

| Vacant lots | 4 frontage on Pape | 1 | Vacant lots | Store, s e | Store, s.e. | ||||||||||||||

| Vacant lots | 4 | 3 | Private Grounds | ||||||||||||||||

| Vacant lots | 4 | 5 | |||||||||||||||||

| Vacant lots | 4 | 7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Vacant lots | 4 | 9 | |||||||||||||||||

| Vacant lots | 7 | 11 | |||||||||||||||||

| Vacant lots | 7 | 13 | |||||||||||||||||

| Vacant lots | 8 | 15 | Unfinished house | Taylor Edward | Clifford C H | Taylor Edward S | Taylor ES | Clifford James | Fredenburg George A | Clifford Caroline Mrs | Clifford Caroline Mrs | Clifford Caroline Mrs | Clifford Caroline Mrs | Clifford Caroline Mrs | Clifford Caroline Mrs | Clifford Charles | Clifford Charles | Clifford Charles | |

| Vacant lots | 8 | 17 | Wellings George | Wellings George | Wellings, Annie M. and George Wellings | Wellings George | Wellings George | Wellings George | Wellings George | Wellings George | Wellings George | Wellings George | Wellings George W | Wellings George W | Wellings George W | Wellings George W | Wellings George W | Wellings George W | |

| Private Grounds | Private grounds | ||||||||||||||||||

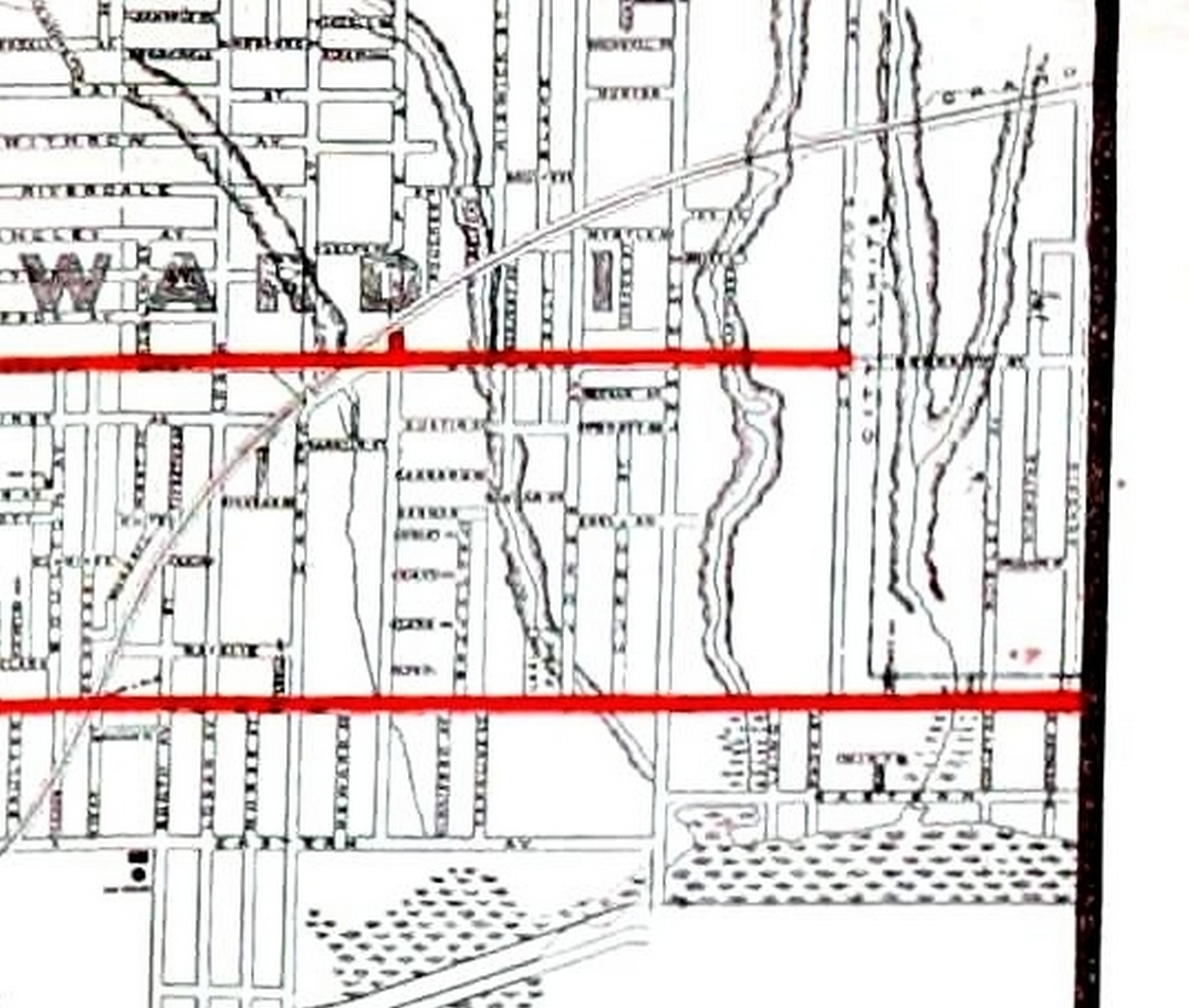

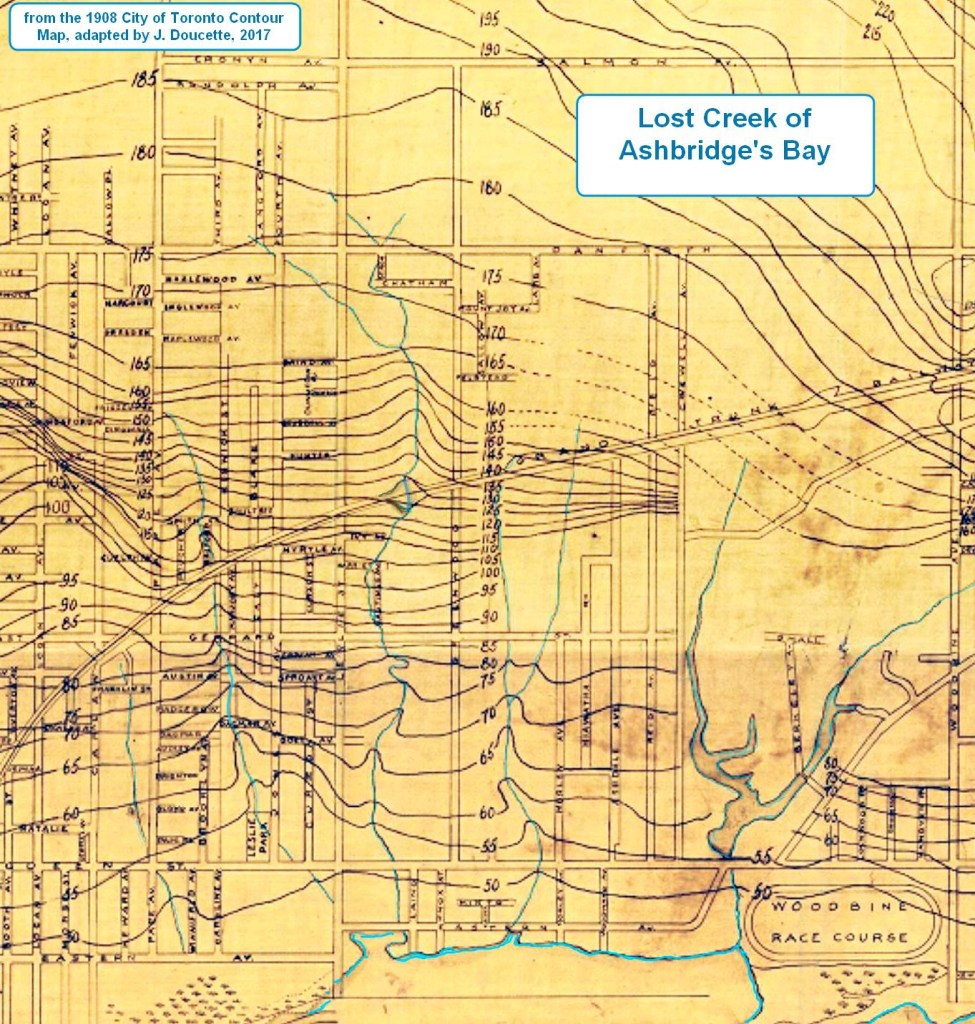

From Tremaine’s Map of the County of York, 1860

From Tremaine’s Map of the County of York, 1860

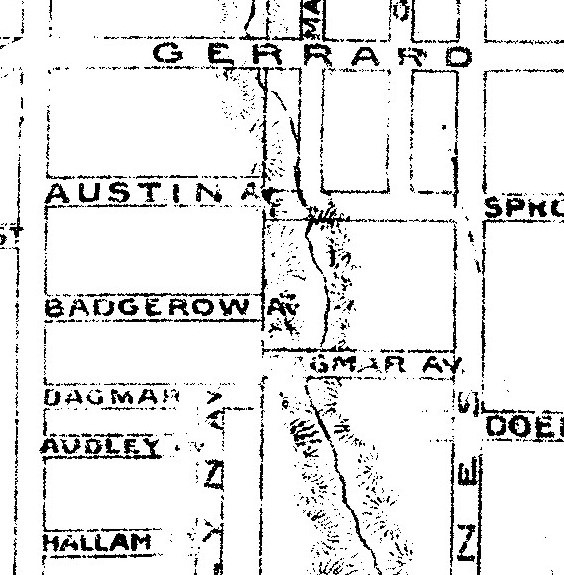

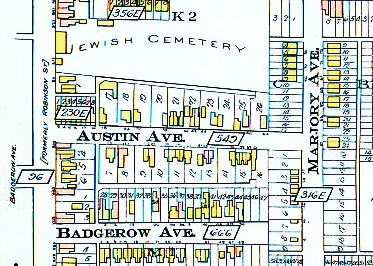

Leslieville showing Gerrard Street East (Late Ramblers Rd.) at top of map. Detail from Goads Atlas 1890 Plate 47

Leslieville showing Gerrard Street East (Late Ramblers Rd.) at top of map. Detail from Goads Atlas 1890 Plate 47