Stanley Minstrels, The Globe, March 9, 1855

A selection of articles from March 6 through the years.

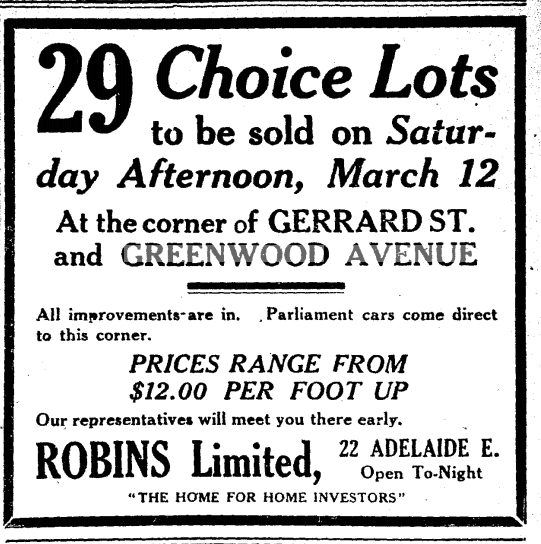

Natural gas, odourless and invisible, seeped into pockets in the shale and overlying gravel in Leslieville. Joseph Russell Junior’s brickyard stretched between Leslie Street and Greenwood Avenue, south of Gerrard to what is now Dundas Street. In 1908 workers were digging clay in the bottom of a 50-foot-deep pit. One worker swung his pick down and struck a pocket of gas which rushed out, splattering clay all over. Joseph Russell had workmen bring in a three-inch auger and insert pipes into the ground. Workers then lit the gas. It burned for three days:

This is not the first indication of the presence of natural gas, however, for some thirty years ago two men were overcome with it while digging a well on Jones avenue, near Queen street. Mr. Russell intends making tests to ascertain whether the [gas] is present in paying quantities.”[1]

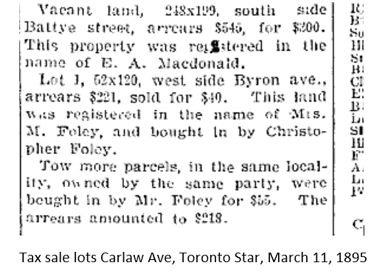

Over 30 years before, on March 1, 1866, George Brockwell (1822-1866) asked well digger and brickmaker, Charles Sear (1816-1866), to work on his well at his house at 138 Jones Avenue, just north of Dundas Street. Sear ran a ladder down, set up a block and tackle over the well and went down to clear out the blocked well. George Brockwell and Sear’s assistants, probably younger family members, stood nearby, watching the proceedings, ready to haul up the excavated soil. Sear had only worked for a few moments when they saw him “topple over against the ladder”, unconscious. His helpers froze, but Brockwell went to Sear’s aid.

No one thought to tie a rope around Brockwell, a common safety measure among experienced well-diggers. Perhaps they thought Sear had a heart attack, or perhaps it was simple inexperience. In any case, Brockwell passed out backwards next to Sear. If the gas had not already killed them, by this time, the water was rapidly rising in the well and they were in danger of drowning.

By this time, the shouting of the lads drew the women of the family and neighbour David Wagstaff (1841-1928), George Brockwell’s brother-in-law and a seasoned brickmaker. Wagstaff tied a rope around himself and went down the ladder only to pass out. The women pulled him back to the surface as three times he tried to rescue Sear and Brockwell. Three times he failed, passing out. After the third heroic attempt, Wagstaff was unconscious for five hours.

Bad news travels fast in rural villages and it was not long before it reached the Leslieville School only two blocks away. Teacher Alexander Muir closed the school and sent the children home. The oldest Brockwell girl led the other Brockwell children home to the tragedy. Muir went along, willing to help in any way he could, but it was too late.[2]

Natural gas may be behind a mysterious explosion in 1930 in the A. H. Wagstaff brickyard at 348 Greenwood Avenue. A tool shed blew up leaving only splintered wood and pieces of stove iron. No one was in the shed which was in a deep shale pit. Employees rushed to the scene. The building, the stove and the tools were literally blown to bits.[3]

Someone must have dropped a cigar or pipe or perhaps one of the lanterns at the well head lit the gas. Flames spouted out of the well. The men tried to smother the blaze by covering the well, but tongues of fire erupted from the ground in other places around the property, burning until finally smothered.

[1] Toronto Star, September 18, 1908.

[2] King, George B. Fond Memory and the Light of Other Days: The Old Leslie Street School and a Last Century Tragedy “over the Don”. (Toronto: privately printed, no date), pp. 6-7.

[3] Globe, February 6, 1930.