Self-guided Tour: Bricks, Devils and a Pocket

Your mission …to explore strange familiar worlds; to seek out life amid urban civilization; to boldly go where everyone has gone before.

By Joanne Doucette

INTRODUCTION

This self-guided tour encompasses the area bounded by Danforth on the north, Gerrard Street on the south, Jones Avenue on the west and Greenwood Avenue including the east side. Enjoy!

By 1900 the brick industry was changing. Small, family-run operations run as a craft were could no longer compete. The easily-accessed soft blue clay near the surface along the creeks and the shore of Ashbridge’s Bay was running out. Machines were replacing hand labour and simple equipment. Women and girls were no longer welcome in the brickyards and neither were very young boys. In the earlier brickyards the whole family worked including children as young as three or four. craft, family-oriented, small scale. The early brickmakers did not advertise and simply served those who came to the brickyard gate to buy brick.

By 1900 brick manufacturers turned to a soft sedimentary rock, shale, to make “shale brick”, but that shale lay deep below the surface and extracting the raw material became what we know of as open pit mining. More capital was needed for heavy machinery, advertising and shipping by rail. Capitalists stepped it and some were no longer brickmakers themselves. The owner of Standard Brick was a medical doctor.

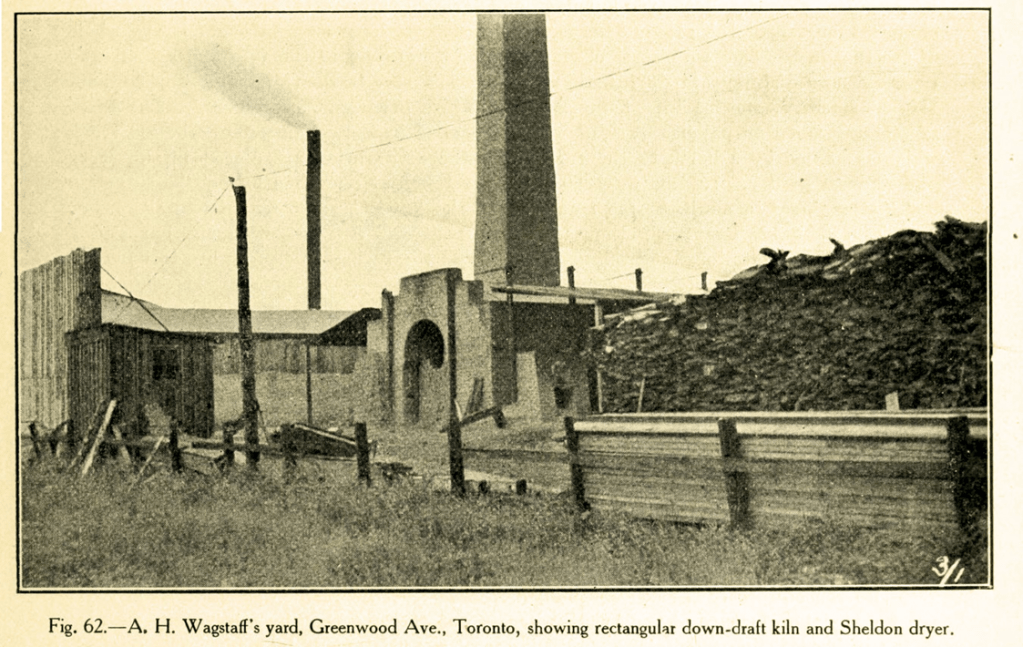

Soon 1905 four brickyards lay north of the rail line on Greenwood Avenue. They extracted blue clay and shale from deep quarries here by blasting with dynamite. It was dangerous and noisy. A steam shovel set on a railroad car on a portable narrow-gauge rail line hauled the broken rock up from the deep quarries to the brick plants at surface level along Greenwood Avenue. The shovel and the locomotive were called “a Dinky”; the cars were “Dinky cars”. Workers loaded the raw bricks onto pallets and then placed pallets on steel cars which ran into Sheldon and Sheldon drying tunnels. Brickmakers fired the dried bricks in scoved kilns or in up-draft kilns. In some cases rectangular down draft kilns were used.

All the four of the first brickyards north of the tracks turned out “very excellent hard red brick”. (M. B. Baker, “Clay & the Clay Industry of Ontario” in Ontario Bureau of Mines, no. 5, 1906, 110-111) The number of brick manufacturers on Greenwood quickly multiplied and the shale pits grew wider and deeper. By World War One the pit on the west side of Greenwood stretched almost to Danforth Avenue as did the quarry on the east side of the road. Each pit had more than one brick manufacturer working in it, each owning a piece of the valuable property in the hole. Originally each brick manufacturer dug their own hole but soon the holes merged together.

The brick industry began to reorganize after 1900. Brick plants and brick pits grew larger and larger brickyards, and even while becoming more and more mechanized, hired more workers until they were a major employer in the East End. As they mined deeper and deeper deposits, heavy machinery became essential and the industry became even more capital intensive so that bigger companies drove smaller companies out of business or gobbled them up just as their machinery was gobbling up the landscape.

Builders and architects began to experiment with new forms and new building materials. From around 1900 brickmakers competed with manufacturers of cement bricks and blocks. As steel-framed buildings became more common, brick was no longer a structural element and became a veneer. The design of modern office towers and factories called for cement, not bricks. Art Deco in the 1920’s fashioned a Toronto downtown with elegant cement buildings.

Brickmakers had to use modern dryers, steel trucks, automatic cutting tables, disintegrators, brick machines, mould sanders, etc. to compete. One dry press machine could make more bricks in a day than the traditional hand-moulding brick yard could make in a year. To survive they had to expand their markets beyond the local builders and contractors who picked bricks up at the brick plant gate. There were fewer and fewer brick manufacturers. Essentially, there were several brick manufacturers sharing one big hole on the east side of Greenwood and others, including Albert H. Wagstaff, on the west side of Greenwood. By the 1930’s large plants using modern methods and machinery shipped bricks across the province from production centres. There were only 14 plants in York County in 1930 compared to 30 in 1906.

STOP ONE: GREENWOOD YARD TTC

Just as the good blue brick clay was being used up, houses built of the very same brick spread over the East End, making remaining clay deposits inaccessible. Only shale was left and the shale pits, hemmed in by housing, could not expand. They could go down deeper. By the 1930’s, only the Price brickyard remained at 395 Greenwood Ave on the east side and was part of the Toronto Brick Company. It closed in 1946. In 1962 Price’s Parkhill Martin machine was moved to Don Valley Brickyard where it was reconditioned and is now on display at Evergreen Brickworks.

The derelict brickyards became subdivisions, schools and parks. Torbrick Road and its housing project, sit on the site of the yard. The Russell and Morley brickyards became Greenwood Park. St. Patrick’s Secondary School and Monarch Park Collegiate sit on old brick pits. Felstead Park was also a brickyard (Logan’s). St. St. Patrick Catholic Secondary School, its playing field and the housing south of it are all sitting on brickyards and claypits.

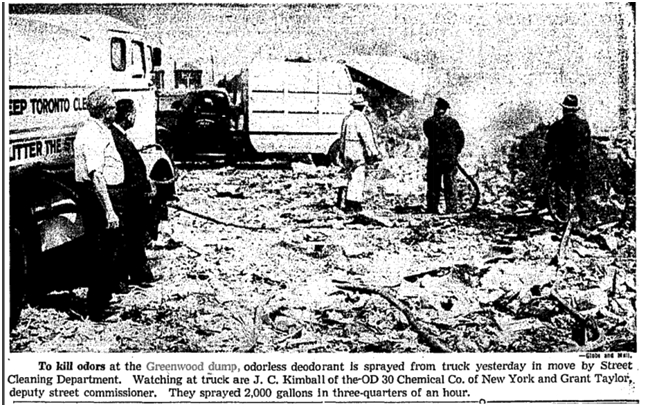

Manufacturers used other brickyards for factories. The big brick yard on the west side of Greenwood Avenue became Harper’s Dump, the City of Toronto’s main garbage tip until 1952 when it was full. They also used the Price brick pit across the street. Dumping then shifted south of Eastern Ave, east of Leslie Street, filling the last of the Ashbridge’s Bay wetland. In 1965 the TTC opened the Greenwood Subway Yard, a 5,600-cubic meter car service and storage yard. 31.5 acres were purchased and some houses torn down make room for the yards. The Greenwood Yard opened at the same time as the first Bloor-Danforth subway line. Subway trains are cleaned, repaired and otherwise maintained at the Greenwood Yard. They are usually stored outside. The TTC has three yards, including the Greenwood Yard, that take care of the subway trains and the machinery needed to maintain tracks.

STOP TWO: TORBRICK ROAD AND THE JOHN PRICE BRICKYARD

John Price was born in Bridgwater, Somerset, England, in 1845. His family had been brickmakers for generations. In 1869 John Price came to Canada and become a farmer, but it wasn’t long before he became a brickmaker again. In 1878, John Price founded his own plant on Greenwood Avenue. Among connoisseurs of bricks (they exist) the John Price red is considered perhaps the best brick ever made in Canada. It was a high quality face brick, used for the exteriors of buildings. Like many brickyard owners, John Price also dealt in real estate and development. His brickyard continued to grow becoming an even larger pit and a large employer.

In 1909, the Taylors, papermakers at Todmorden on the Don, sold their Don Valley Brickworks to Robert Davies. The Don Valley Brickworks and the John Price Brick Company were competitors, later to become one. The clay in the first John Price brickyard became depleted and John Price opened operations further north, above the GTR tracks, on the east side of Greenwood Avenue. John Price died May 27, 1916, but there were no shortages of Prices to carry on brickmaking.

By the 1920s the John Price red facing brick was the mark of a well-built, valuable home, used in Forest Hill and other upscale Toronto neighbourhoods.

In 1928 the Brandon Brick Company of Milton, Ontario, and the John Price Brickyard on Greenwood Avenue amalgamated to form the “Toronto Brick Company”. However, by the 1930’s, a combination of increased demand for bricks and mechanization of the brickmaking process depleted the brickfields. The land became too valuable for brickmaking. The anti-smoke bylaws limited heavy industry.

The only brickyard left operating was Price’s yard at 395 Greenwood Avenue. It became the Toronto Brick Company. The Toronto Brick Company closed in 1956 when the United Ceramics Limited of Germany acquired the Toronto Brick Company. It was Leslieville’s last brickyard. In 1962, the company relocated the Parkhill Martin Brick Machine from the former John Price Brickyard to the Don Valley Brickworks to make soft-mud bricks for the “antique” brick market.

STOP THREE: ALBERT WAGSTAFF, LIVE AND LET LIVE — AND PARTY

Albert “Bert” Wagstaff was the Alderman Ward I and openly lived by “Live and let live”, making him seen as a man’s man, but also a womanizer, drunk and party animal. Wagstaf made all the varieties of brick then in demand but also specialized in purple and black brick. He lived at 326 Greenwood Avenue, a large house, hidden by later factory additions. He was a builder too. When he had an oversupply of bricks he built low-rise apartments including the Alberta and Louise on Dundas Street, the Avalon Apartments. and possibly Morley Court Apartments at Woodfield Road and Gerrard Street. He was known for having multiple mistresses, all of whom knew each other and were not adverse to partying solo with Bert or en masse. Family legend has it that he put a different mistress in each one of those apartment buildings — except The Vera. When he died, this not-so-upstanding Methodist brickmaker left his brick business to a drinking buddy, Albert Harper. Much of the rest he left to the daughter he adored, Vera Sparks. His marriage to his second wife was the kind the devil would have bolted out of hell to escape. He left her and the son who had turned against his father, very little. They sued and lost — after all a man’s home was his castle and he could do with his millions what he would.

STOP FOUR: THE DEVIL’S HOLLOW — BEDEVILING THE POLITICIANS

In 1882 Gerrard Street was extended east to Logan’s Lane and the side lines (the side streets of today) were opened out. The extension of Gerrard Street allowed a way for people to avoid paying tolls on Kingston Road, decreasing the toll keeper’s revenues. In the 1890’s cash fare was 5 cents and one could buy 25 tickets for a dollar to ride the streetcar. Streetcar service was the essence of suburban life at that time and dissatisfaction with the Toronto Street Railway Company was perpetual. In December another district street car line was created along Gerrard Street East to Pape Avenue. In 1901 Alderman Oliver moved that the City Engineer report on the cost of extending of grading Gerrard Street from Pape Avenue to Greenwood Avenue “making if fit for street car tracks”. (Globe, September 17, 1901) The obstacle was a deep ravine, dug it even more by brickmakers, south of the railway tracks between Jones and Greenwood. It was called the “Devil’s Hollow” or “Devil’s Dip”.

In 1903 The York County Council considered the state of the roads and whether they should be improved. “Councillor Baird stated that he was very much opposed to paying out money for good roads and then have “the automobile fellow” come out on them from Toronto. He stated that these machines went at a terrific rate, and were very dangerous.” (Toronto Star, November 27, 1903)

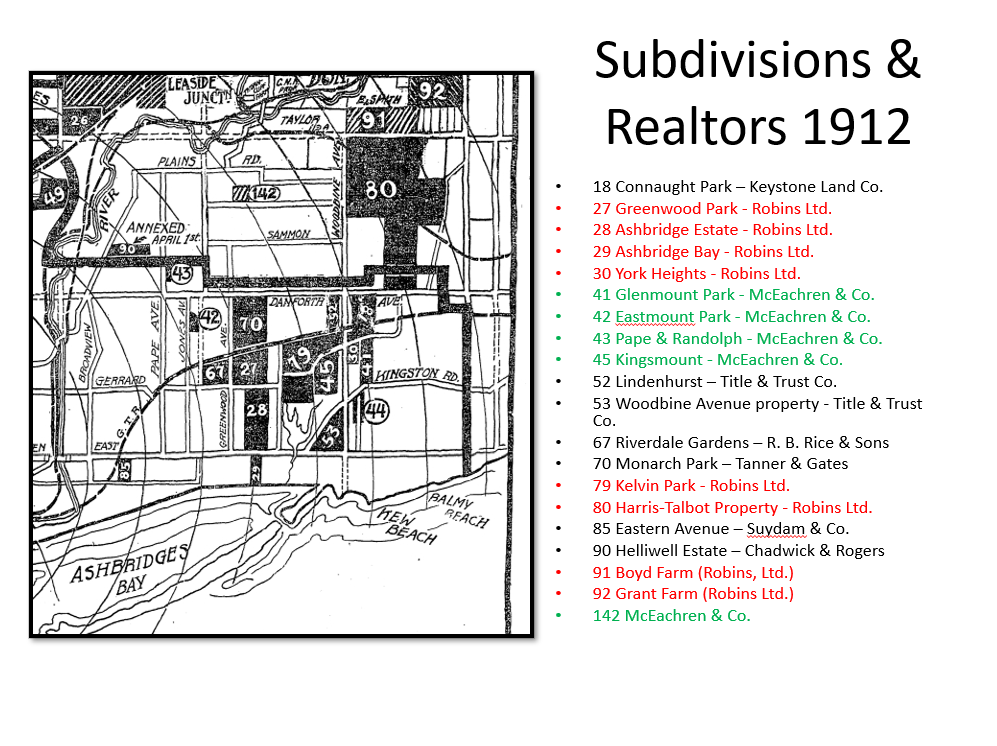

In 1906 the Gerrard street car line was extended to Greenwood Avenue. Expectations rose in 1909 when the Area south of the Danforth between Don and the Beach was annexed by the City of Toronto. It was called Midway” by many. The boom was on. Empty spaces east of the Don filled up so that the area was fully developed by World War I. Real estate boom developers advertised a popularized form of the Arts and Craft bungalow, calling them “California-style bungalows” (Globe, April 14, 1922), and larger square Edwardian houses, called “villas”. Many of these buildings are remarkable similar in style — few models were apparently used. But there were exceptions. Many working class people also built their own homes and these houses may stand out on a street of “clones”.

In 1906 workers filled in the Devil’s Hollow with sand and gravel dug from the widening of Coxwell Avenue. Small locomotives carried the fill down to Prust Avenue and Gerrard Street on a light rail line laid specifically for the purpose, but the grade was still very steep.

In December, 1912, street cars began operating along Gerrard Street east of Pape. Mayor Hocken and City Controllers inaugurated the new Civic Streetcar line on Gerrard Street East, December 16. The Mayor, Controllers, Alderman and city officials were in the first car. Ordinary citizens were in the others, free of charge for just that day.

After the 1906 fill Hastings Creek still cut a 30-metre deep ravine north of Gerrard Street. By 1917 the soft, loose sand in the landfill under the streetcars had settled and was continuing to settle. The roadbed in the “Devil’s Hollow” threatened to derail the trolleys. The City of Toronto appointed a Committee to inspect “the gully south of Prust Avenue. This spot is considered a danger to public safety.” In 1919, the tracks were torn up again and more fill was dumped in. Now, much shallower, the ravine was considered a problem solved.

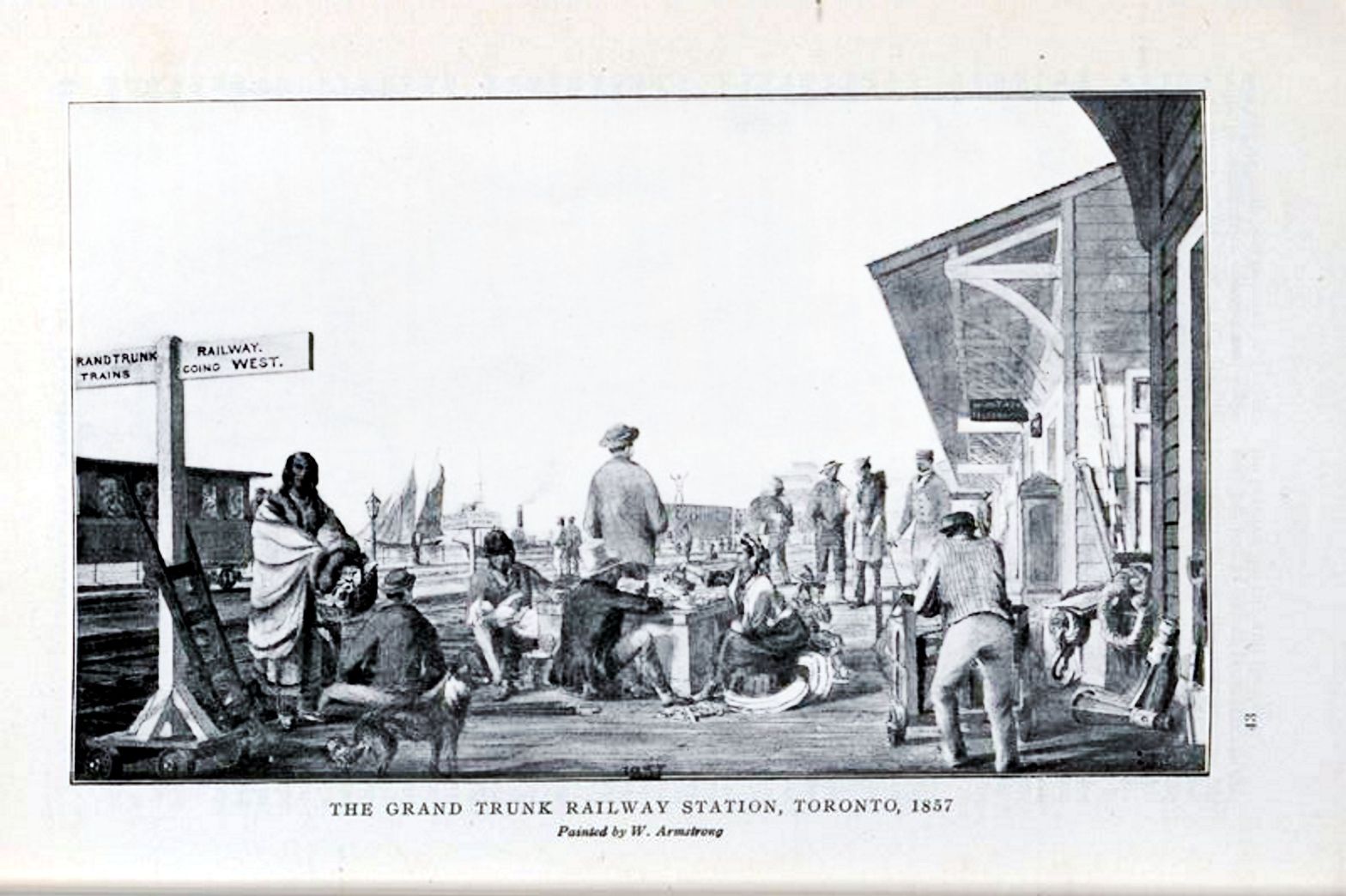

STOP FIVE: THE GRAND TRUNK RAILWAY

1846 to 1849 Irish navvies built Ontario’s first railroad, the Ontario, Simcoe and Huron Union Railroad. In 1847 about 105,000 Irish emigrants left for British North America, driven out of their homeland by the Potato Famine or An Gorta Mor; many landed at the Simcoe Street docks.

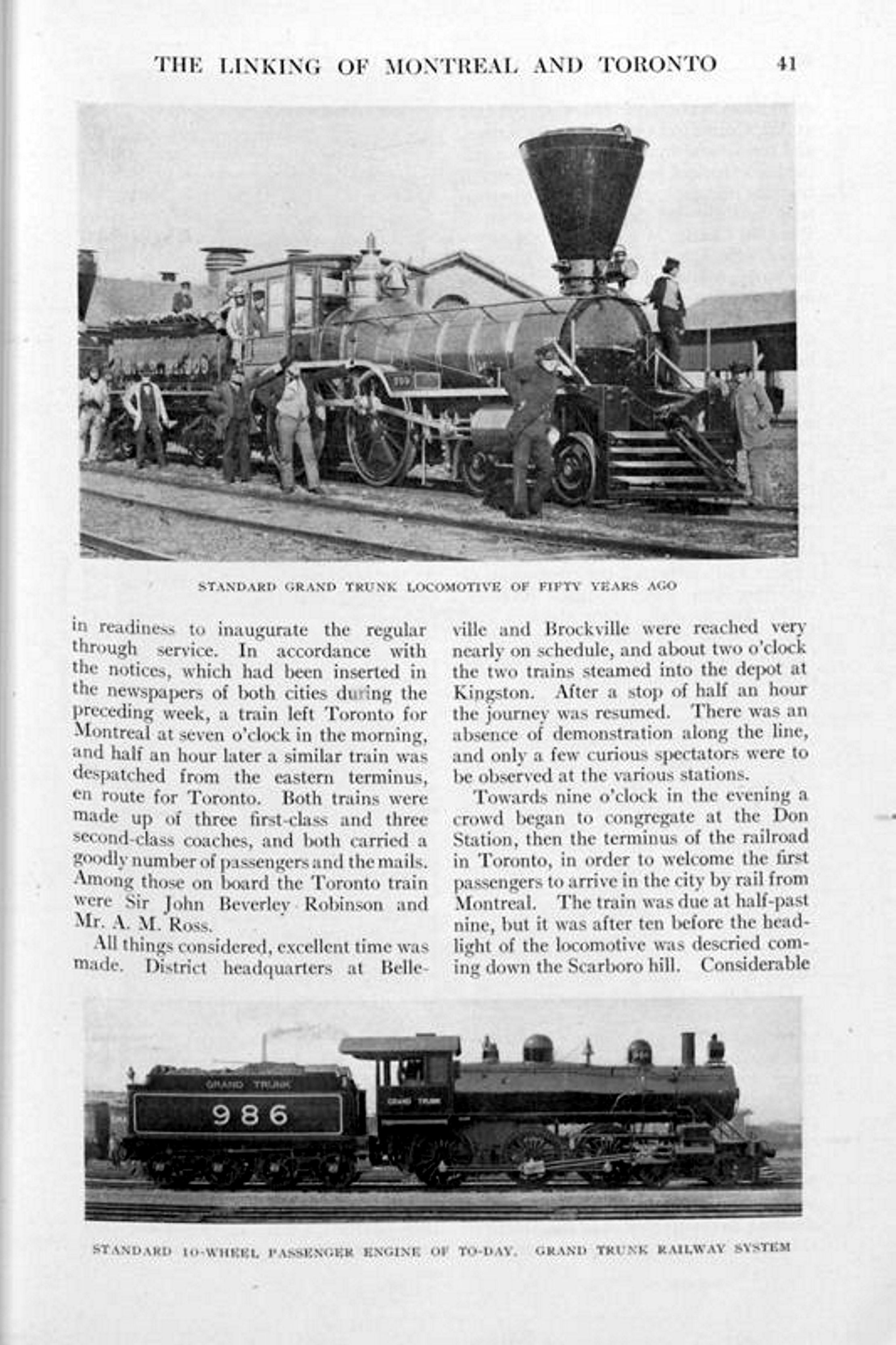

In 1852 the Canadian Government announced plans to build a railway from Montreal to Toronto. The Grand Trunk (GTR) formed and won the charter to build a railway through Canada East and Canada West. Navvies built the line as quickly as possible. In 1856 the Grand Trunk Railway advertised that it was opened “Throughout to Toronto on Monday October 27”. The chief freight was grain, tan-bark, timber and cordwood — most of it still the produce of the forest. Irish backs and Irish brawn built the railroads of Ontario. The GTR ran through and local trains.

STOP SIX: JAMES EARL GRAY

6 Condor Avenue was a brothel where James Earl Ray is reputed to have hid out in Toronto after assassinating Martin Luther King on April 4, 1968. In 1993, to mark the 25th anniversary of King’s murder, journalists from the Ottawa Sun and Robert Benzie interviewed Ray at Nashville’s Riverbend Maximum Security Institution. Ray was a master of disguise, using multiple identities to escape capture. On May 6, 1968, Ray boarded a flight to London. The biggest manhunt in history ended on June 8, 1968, when officers arrested him at Heathrow Airport. “I don’t think I have much in common with these others,” Ray told the journalists. “I mean, Sirhan, he’s Arab from Jordan or wherever and Oswald, he was in politics. Here I am. I’m just involved in criminal activity. I just did dumb things like coming back to the United States from Canada.”

STOP SEVEN: THE POCKET

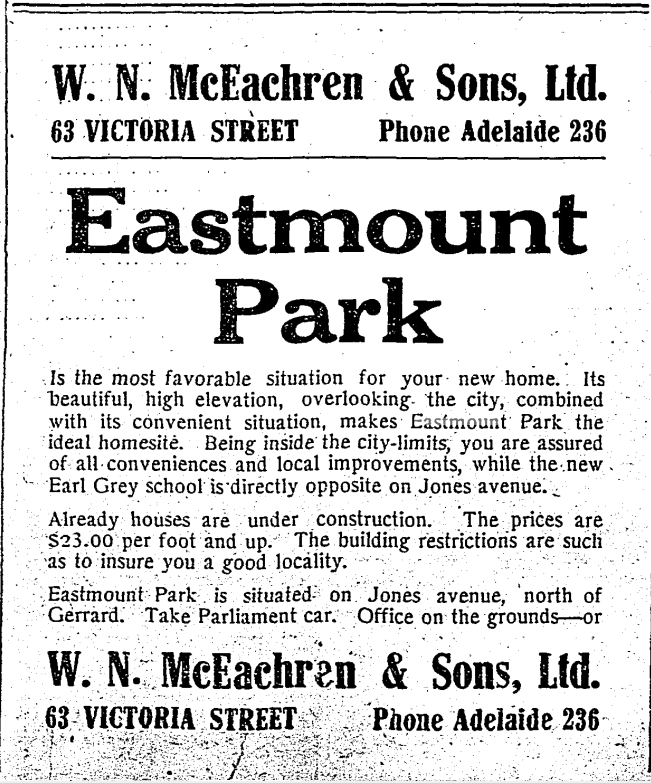

The Pocket lies between Danforth Avenue on the north, the Greenwood TTC yard on the east, Jones Avenue on the west, and the CNR train tracks on the south. The Pocket was originally developed as a subdivision called Eastmount, but that name has been lost in time.

Toronto grew by almost 700% from 1851 to 1901 when some of the older houses in the Pocket were built. The 1880’s and 1890’s were decades of great population growth over the Don also nicknamed The Goose Flats. Reliable, efficient and inexpensive public transit, in the form of the streetcar, was the key to suburban living.

A typical 1912 house: Six-room bungalow: living room, dining room, and kitchen, downstairs; and three bedrooms upstairs: $2,400 – Last one of 6 comfortable homes, East End, brick front, 6 rooms and bathroom, beautifully decorated, concrete cellar and Pease furnace, verandah, $200 down, balance equal to rent; don’t miss this please. (Toronto Star, April 23, 1909)

Susan McMurray, co-founder and co-editor of The Pocket newsletter, and her neighbours made up the name for their neighbourhood, sandwiched between Greenwood Avenue, the subway yard, the rail corridor and Danforth Avenue. They launched their newsletter in 2003. In the 1990’s young urban professionals, nicknamed “Yuppies” somewhat unkindly, began buying houses in the Pocket. Many houses were rundown. The new owners often completely gutted and recreated from top to bottom. At that time, many decorated their walls austerely with white paint so they were also called white painters.

September 26, 1913

An older resident recalled, “a ravine that cut through the area before it was turned into a landfill, then covered with buildings and greenery”. Ravina Crescent, a winding street south of Danforth Ave. follows the route of that branch of Hastings Creek, which was known as Ravine Creek and later Ravina Creek.” The Creek came first, Ravina Crescent followed. In 2006 some 3,000 people lived there. Most were between the ages of 15 and 65, according to a Statistics Canada report commissioned by the newsletter. More than a third were first-generation immigrants, and nearly 40 % identified themselves as visible minorities. Pocket residents work hard at improving their neighbourhood with events such as annual litter-pickups, tree-planting drives and a volunteer-built ice rink in the park. Ben Kerr, a busker and mayoral candidate, was probably the most famous Pocket resident. Ben Kerr Lane is named for him.

STOP EIGHT: THE BRIDGE

Crossing the Danforth At Jones and Danforth was an eight foot wide stream with a wooden bridge over it. (Interview with Harry Clark, c. 1977 in Local History Collection, Broadview & Gerrard Branch, Toronto Public Library)

…to cross the Danforth at Jones one had to go down a set of stairs, cross the road, then climb four more steps on the other side.…further down, on Jones, there was a bridge that crossed a creek which started at Langton, went underground in the direction of Ravina. (Interview with Mrs. Cooper, 456 Jones Ave c. 1997 in Local History Collection, Riverdale Branch, Toronto Public Library)

THE END

Some Lost Leslieville Industries

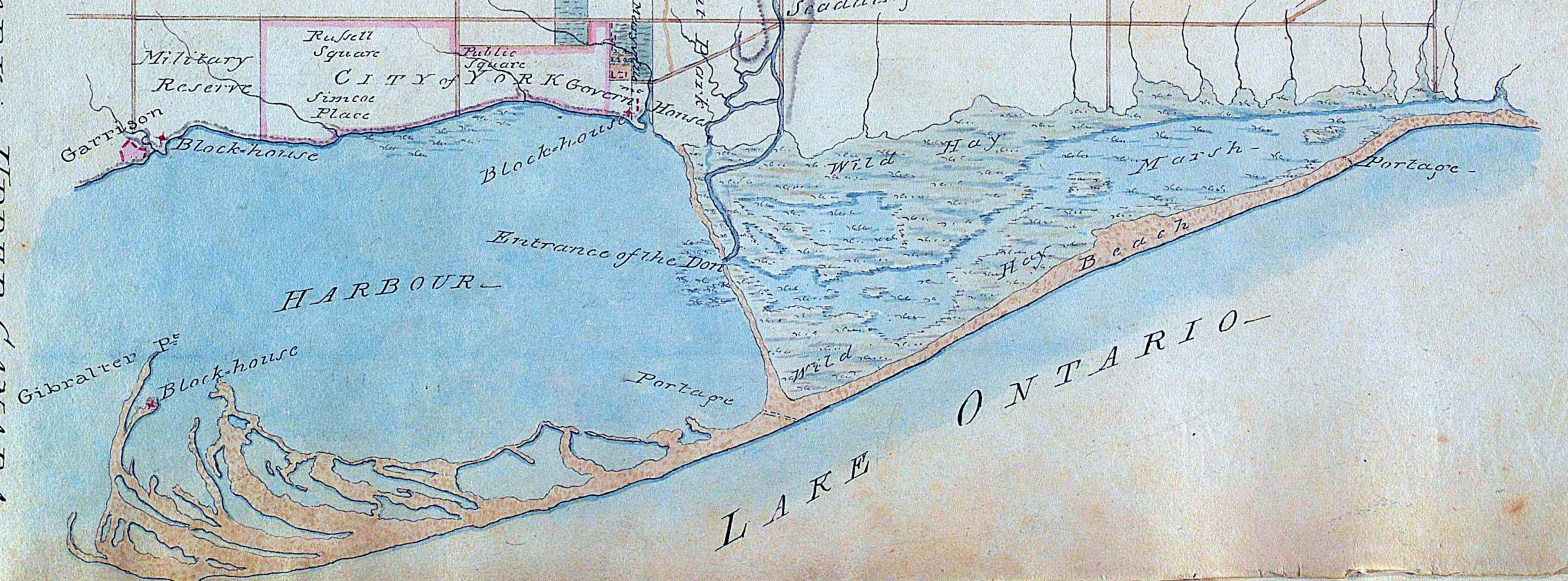

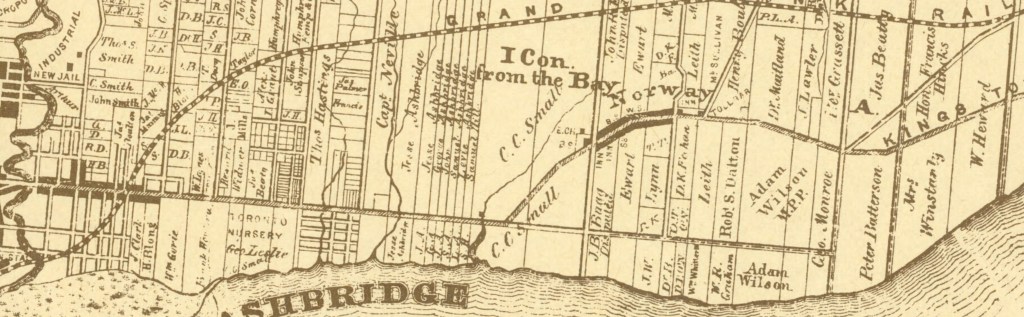

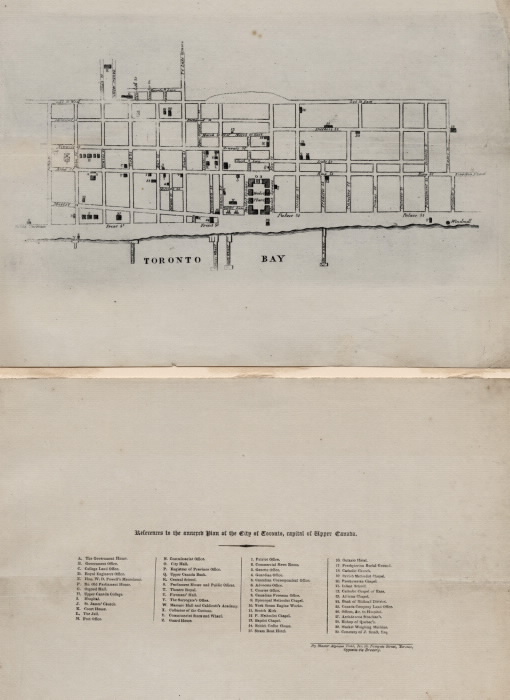

1860 Ownership Map: The area east of the Don River

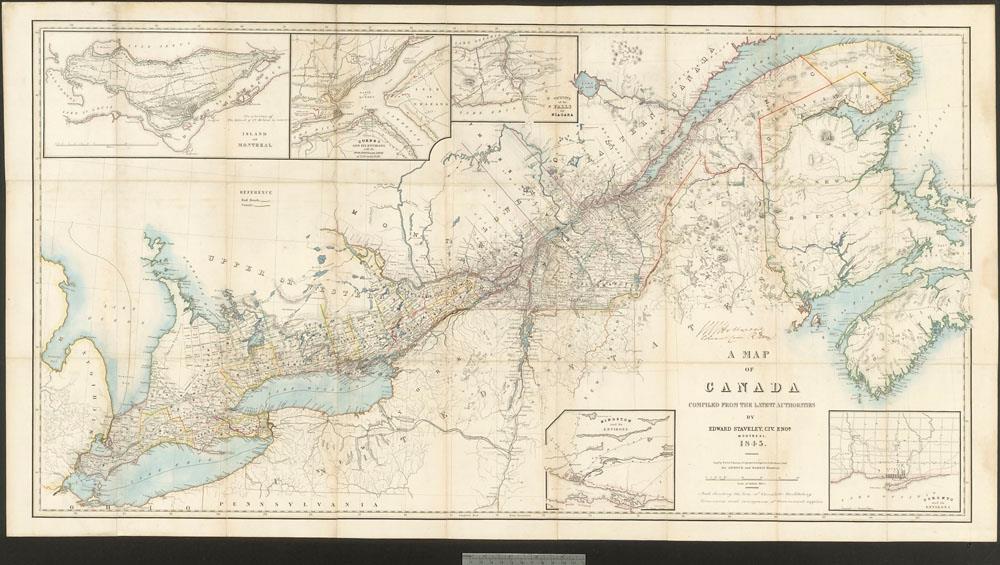

The Linking of Montreal and Toronto

Plaque to Underground Railroad

We hope you will be able to join us for at 11:30 a.m. on November 19, 2019, at The Logan Residences, 899 Queen Street East. The Leslieville Historical Society and The Daniels Corporation will unveil a plaque recognizing the Underground Railroad and the families who made their way to freedom, forming a black community here from the early 19th century.

Here is the wording of the plaque:

“Every great dream begins with a dreamer. Always remember, you have within you the strength, the patience, and the passion to reach for the stars to change the world.” -Harriet Tubman (1822-1913)

Many families came to Toronto in the1800s to escape slavery, violence and oppression in the American South. They courageously followed the dangerous path to freedom via the Underground Railroad and some settled here, near the corner of Queen Street East and Logan Avenue. While a few returned south after the Civil War (1861-1865), many remained, helping to forge the identity of Leslieville today.

This plaque commemorates these families: the Barrys, Cheneys, Dockertys,Harmons, Johnsons, Lewises, Sewells, Whitneys, Wilrouses, Winders, Woodforksand others who came here from Kentucky, Maryland, Virginia and other States.

BY THE LESLIEVILLE HISTORICAL SOCIETYWITH THE

DANIELS CORPORATION AND THEIR PARTNER STANLEY GARDEN

2019

In 1793 Upper Canada passed law banning the import of slaves (first such law in British Empire (9 July). The Abolition Act decreed slave children born in Upper Canada from this day forward are to be freed when they are 25. In the 1840s and 1850s a series of American court decisions and laws tightened slavery’s grip and made escape even more dangerous. Increasingly, refugees from slavery headed to Canada, many using the secret network known as The Underground Railroad, but most travelling alone or in small family groups with no help from anyone, using the Northern Star to guide their way.

By the mid-1860s 60 to 75 black people lived here, out of a population of Leslieville’s population of about 350. We honor their contributions to our community where their descendants still live and work today.

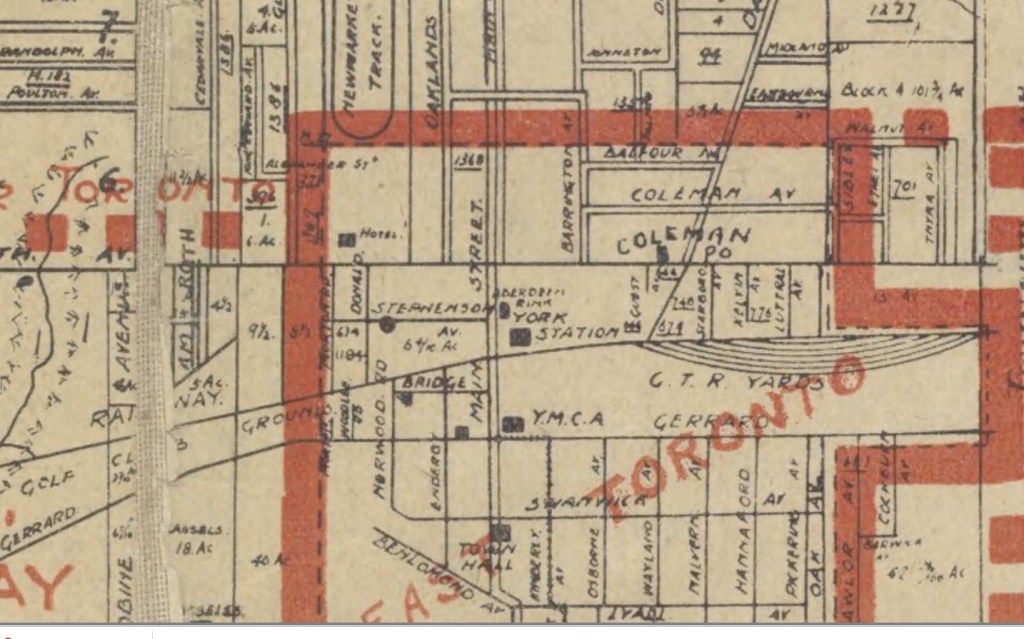

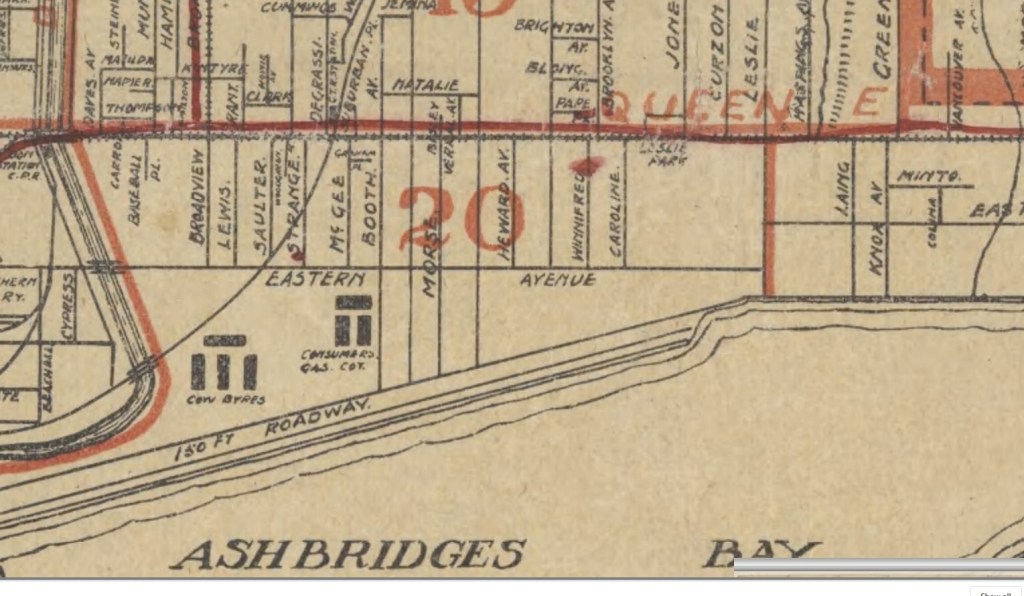

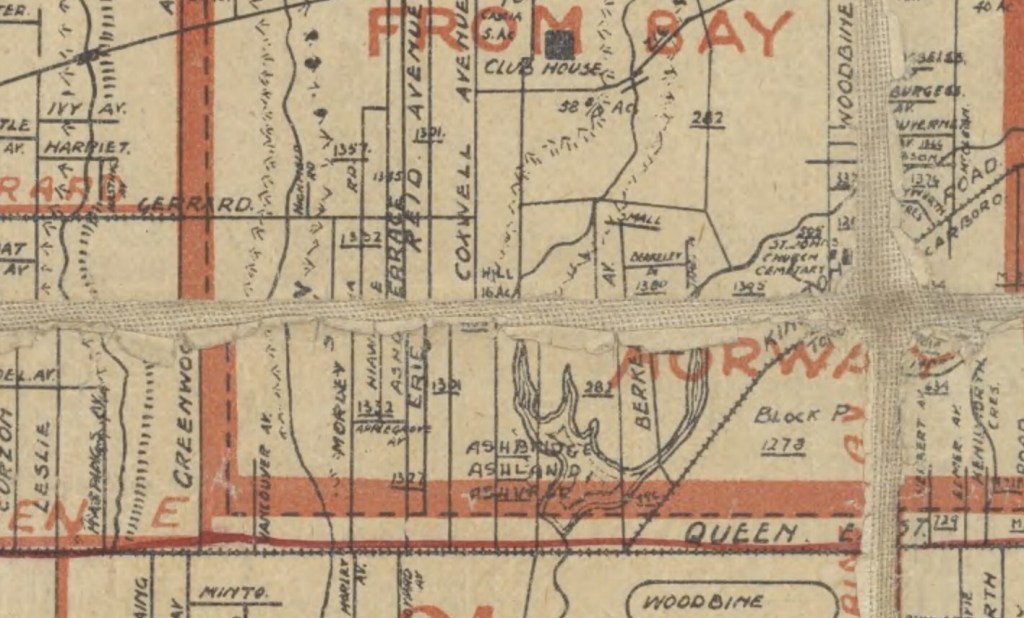

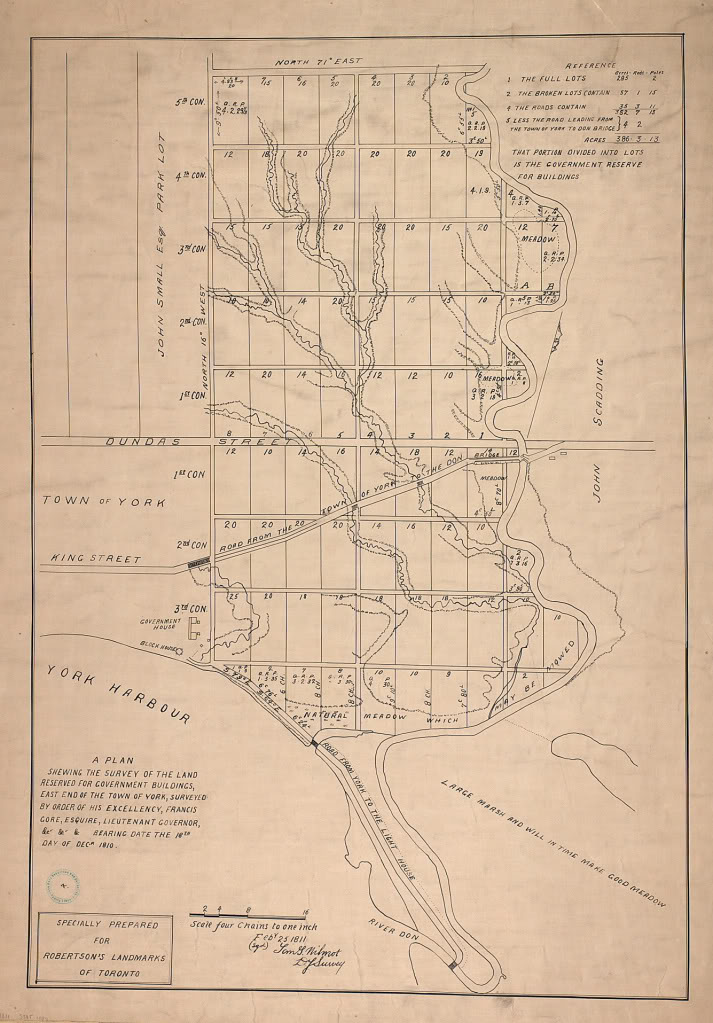

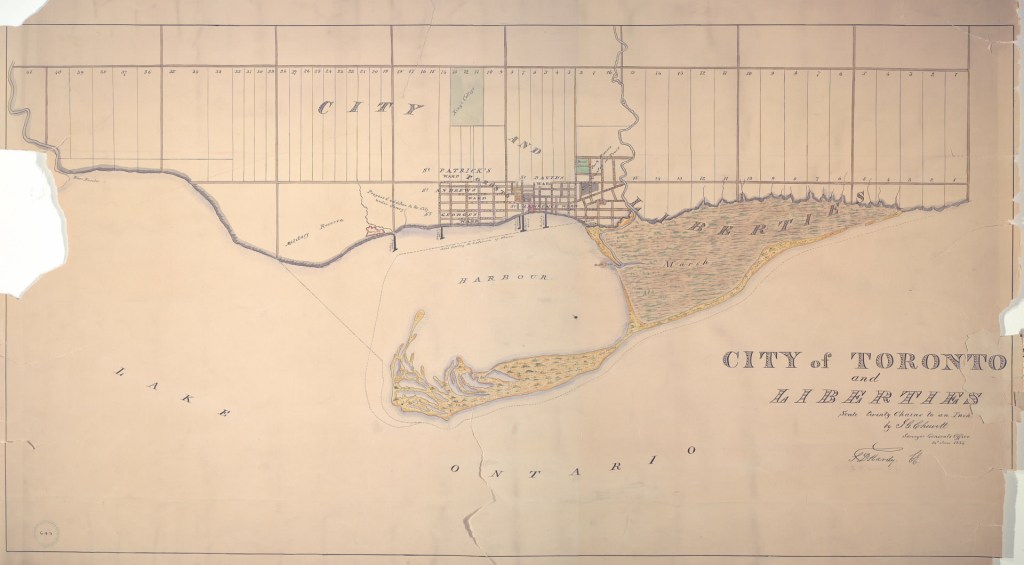

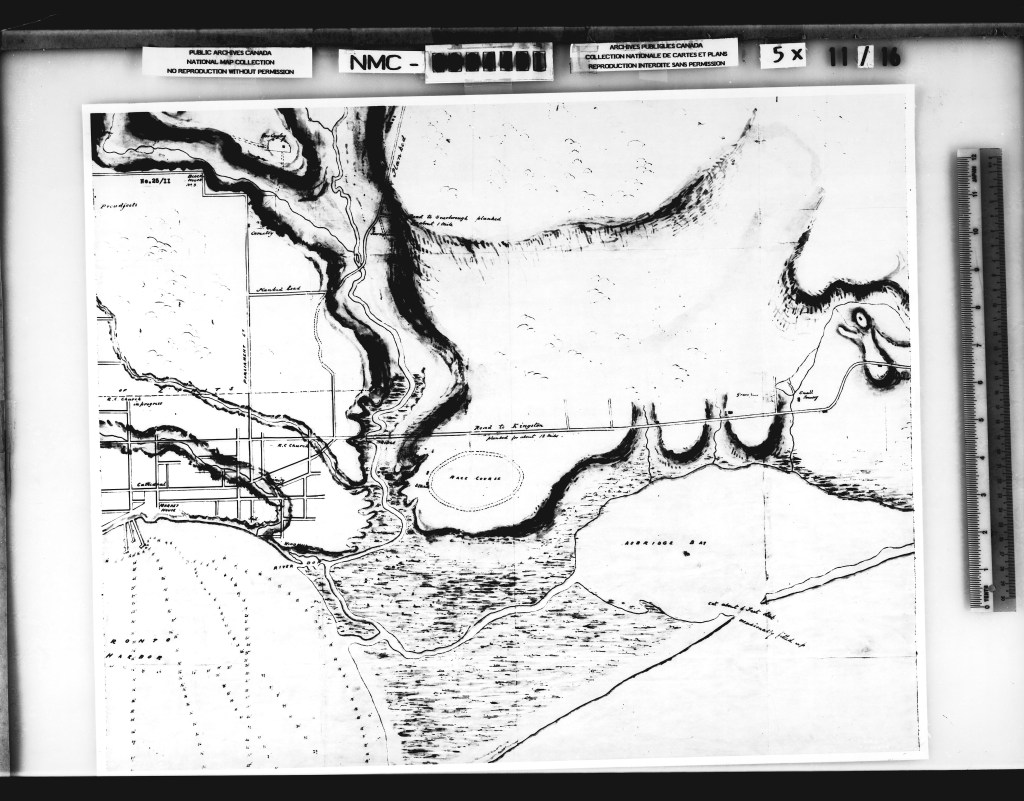

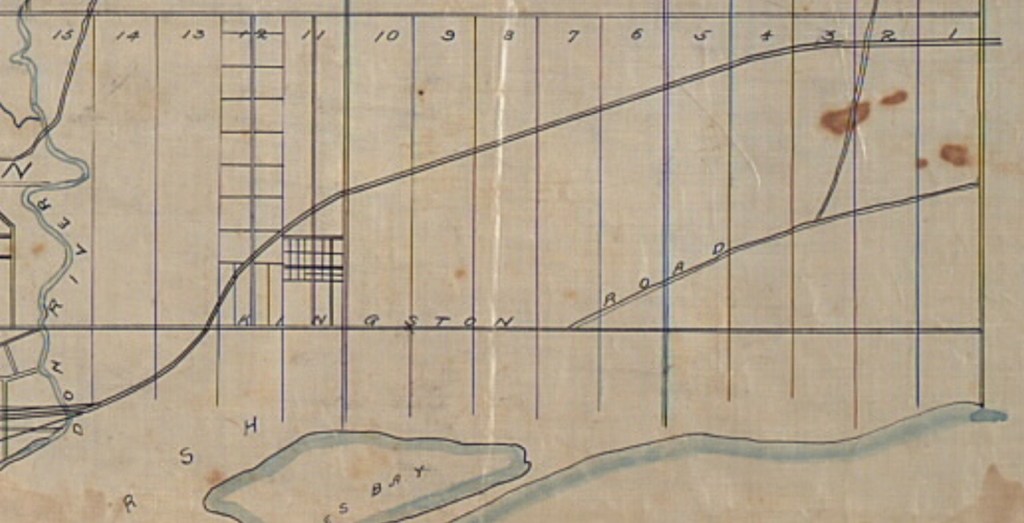

1909 Map: The East End

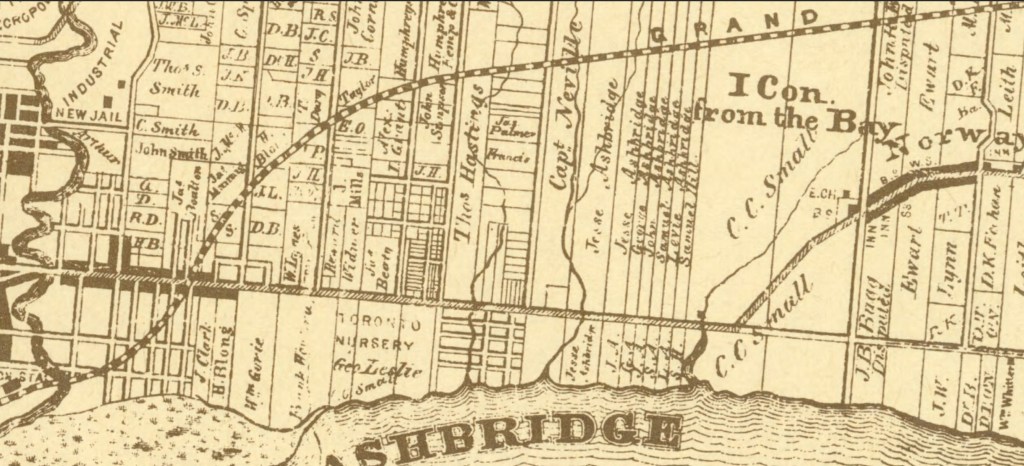

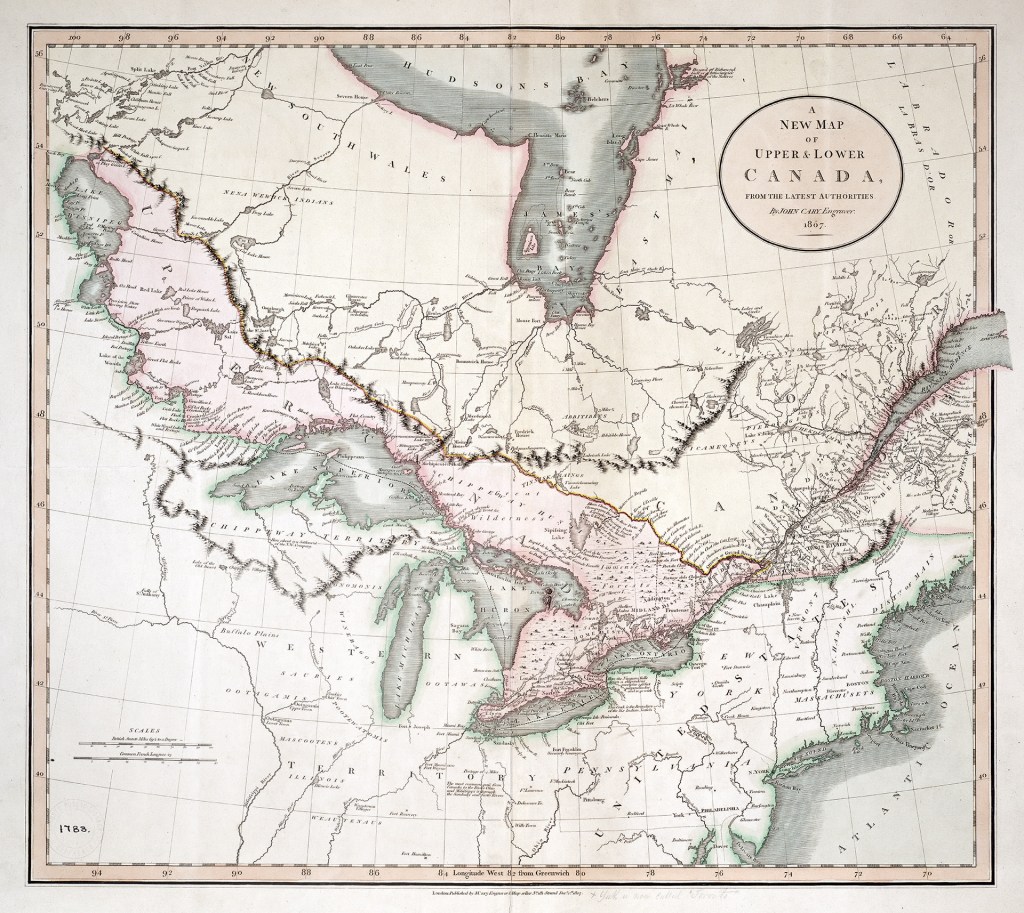

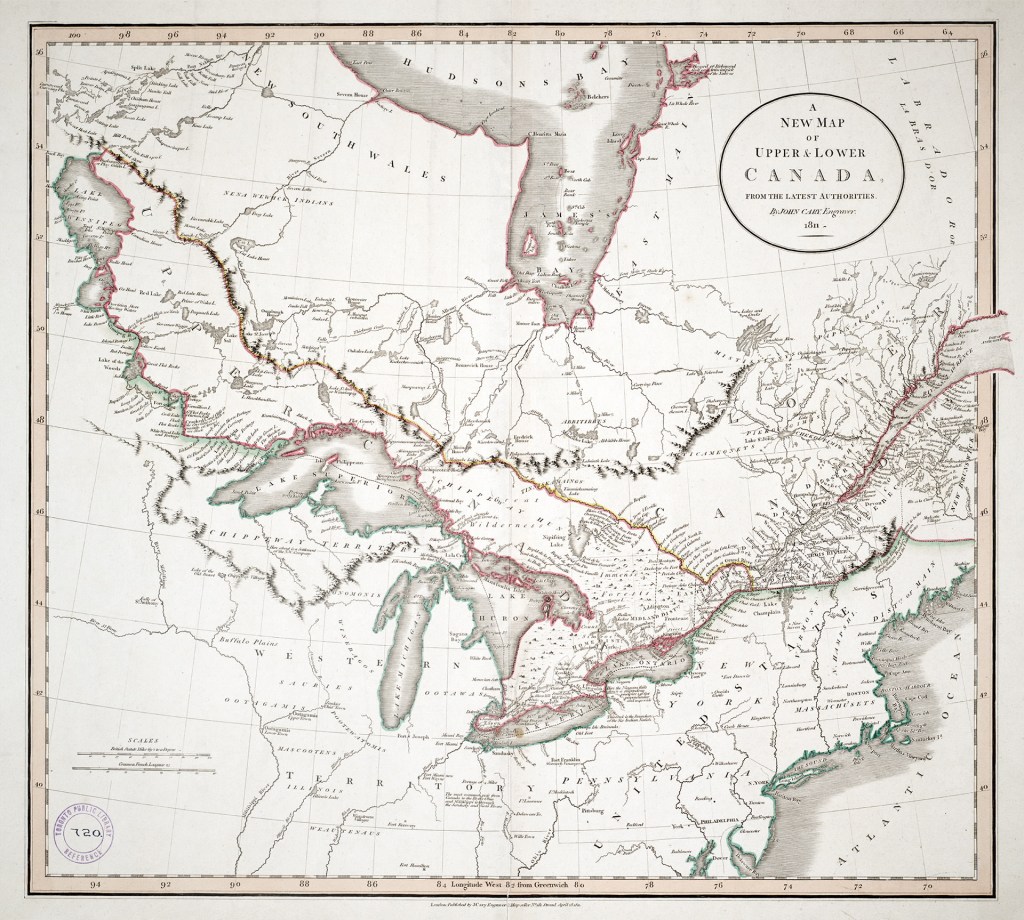

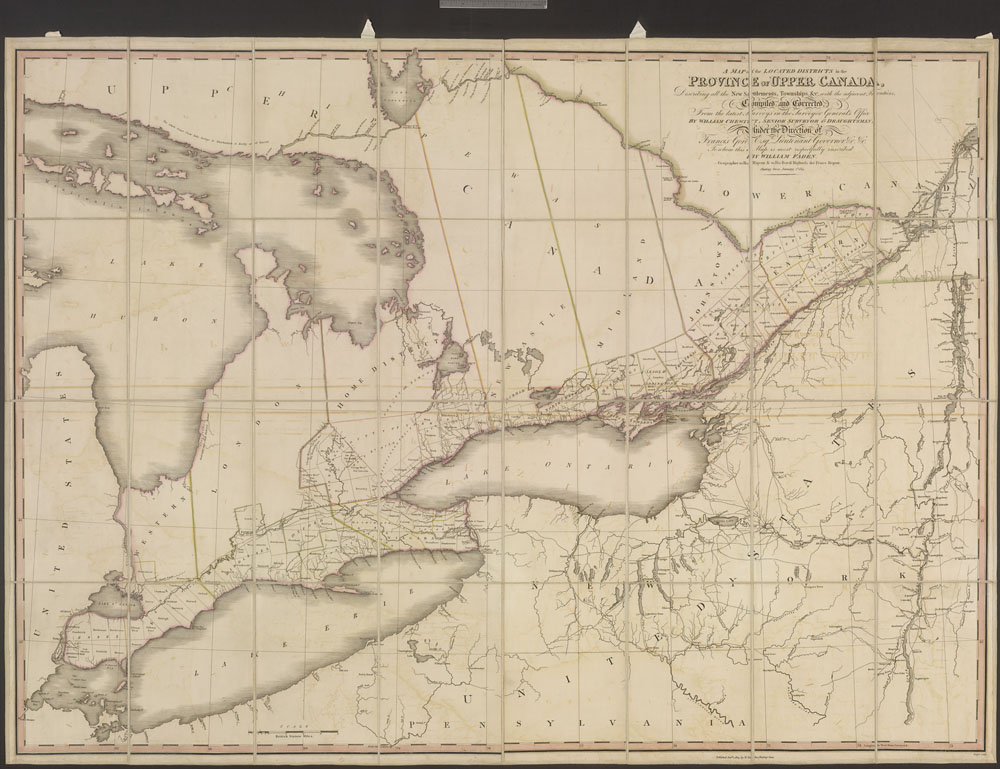

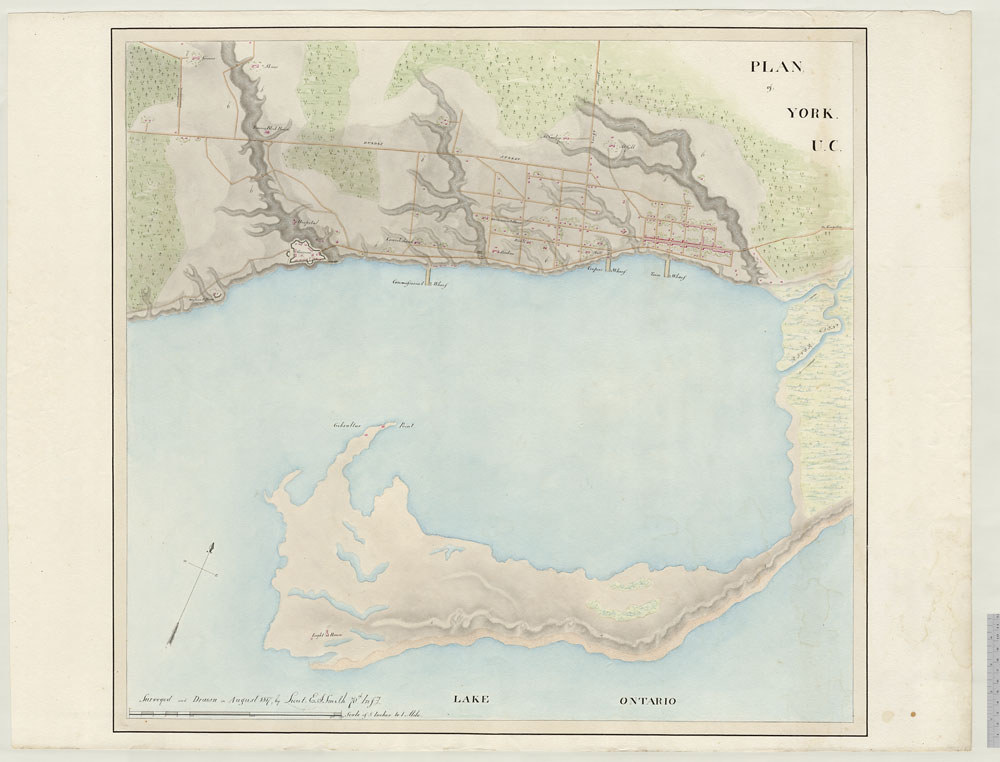

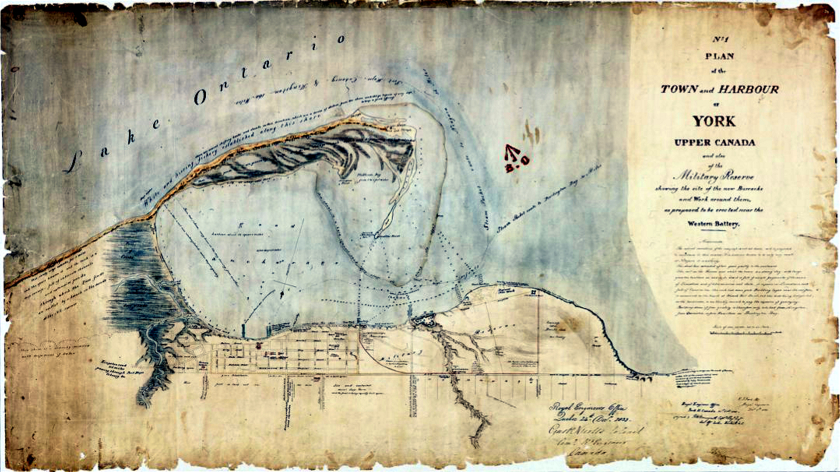

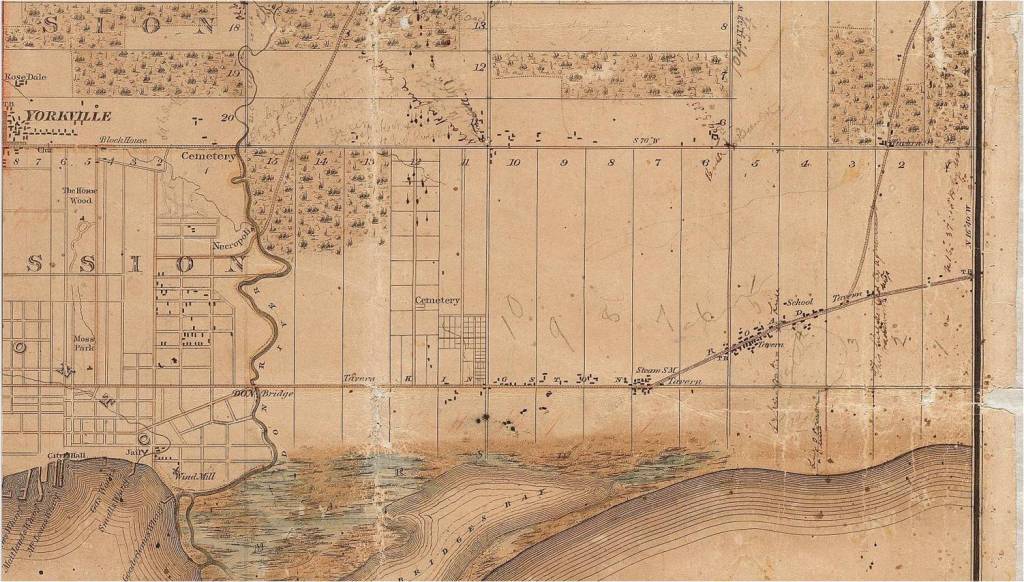

Some assorted maps

1922 Township of York Ownership Map

Horace L. Seymour, O.L.S.

City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 200, Series 726, Item 359

NOTE: The colours of the map have been reversed for increased legibility.

The Secret History of Our East End Streets: 1 – 17 Austin Avenue

London, England has a BBC show, The Secret History of Our Streets. The series claims to explore “the history of archetypal streets in Britain, which reveal the story of a nation.” Our streets are just as interesting and our stories goes back millennia before Austin Avenue existed to when Leslie Creek was full of salmon and Anishnaabe, Haudenosaunee and Wendat gathered wild rice in Ashbridge’s Bay. I hope you enjoy this page. My research ends in 1919, a century ago. I have not explored the history of every family, Austin Avenue has more secrets to tell.

Here are some of those stories — those from 2 to 17 Austin Avenue

2 Austin Avenue

Walter Gray was born on November 9, 1857 in at Gray’s Mills, York Township, now part of the Donalda Golf and Country Club. He married Annie Emma Clifford on January 30, 1884 and they had five children in 11 years. The Grays had a grocery store at 2 Austin Avenue and lived above the store. They moved to 100 Boulton Avenue about ten years later.

His wife Annie Emma passed away on July 29, 1916, on Bolton Avenue, at the age of 49. They had been married 32 years. Walter Gray died on April 8, 1938, in Dunnville, Ontario, at the age of 80.

Son William John was born on December 19, 1885, in Toronto, Ontario. He Gray married Annie Mary Norris on June 28, 1907, in Toronto. They had two children during their marriage. He died in 1948 at the age of 63, and was buried near his parents. Annie Mary Norris died in 1960 and was laid to rest next to her husband. The Gray family plot is in Saint Johns Norway Cemetery and Crematorium, Woodbine Avenue.

Ironically both the Gray family homestead and Leslie Street School principal Thomas Hogarth’s house have been honoured with historical plaques.

4 Austin Avenue

4 Austin Avenue was the home of Henry Bowins in 1919 and, in 1921, by widow, Mrs. Louisa (Beckett) Greenslade and her five children, ranging in age from 7 to 17. in 1921. Her husband, William Henry Greenslade, a market gardener, had dropped dead of a heart attack in 1915. The family lived in Etobicoke at that time.

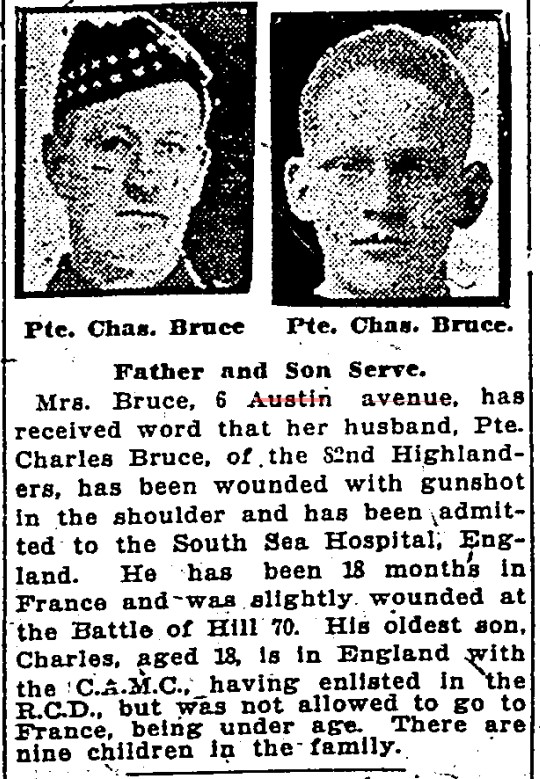

6 Austin Avenue

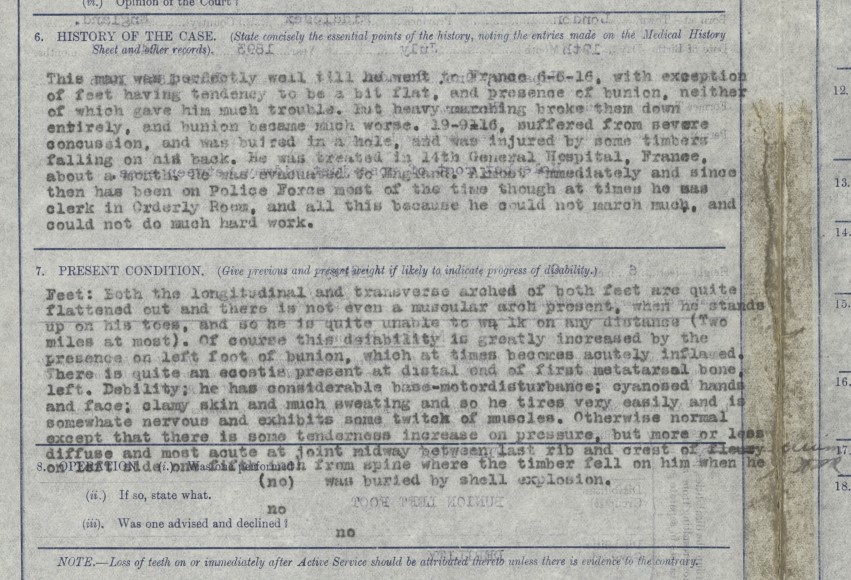

8 Austin Avenue

John Christopher Waldron married William Robertson Hodge’s sister Eveleen in 1919 and was lived with her, sister Jean, and their mother, Mary. Like his brother in law he was a tall man for the time (5’11”) and fit. He was an Irish Catholic while Eveleen Hodge was an Irish Protestant. Both were from Dublin. Unlike his brother-in-law, he was not conscripted but volunteered. Like his brother-in-law he was hit by shellfire. Clearly from the medical records doctors had a hard time identifying just what was wrong with Pte. Waldron, apart from flat feet which was easy. The blast buried Waldron completely under mud, timbers and rubble, causing a severe concussion and what was known as “shell shock “. He died in 1964.

10 Austin Avenue

It appears that Mrs. Robinson at 10 Austin Avenue took in lodgers, as many widows did. Since the lodgers were mostly young men who moved frequently, it is difficult to determine just which Frank Mulhern was responsible, but it appears to have been Frank Beauchamp Mulheron (1881-1917) who moved to the U.S. permanently shortly after this assault occurred. Strong-arm tactics to hijack valuable cargo was not uncommon though this was particularly audacious. Often the motive was to re-sell the produce and sometimes simply to get something to eat. The perpetrators usually knew their victims and counted on intimidation to keep the victims from reporting to the police. Gangs were a reality back then too. Timothy Lynch of 51 Austin Avenue took the law into his own hands shooting those who robbed his orchard. But that’s another story.

Dudley Seymour Robinson was born on July 6, 1892, in San Jose, California, USA,. Both his parents were English. He married Gladys Elsie Moffat on October 6, 1920, in Toronto. They had two children during their marriage. He died in March 1963 in Michigan, USA, at the age of 70. In 1911 he was living with his widowed mother Rosina Alice Robinson at 10 Austin Avenue and working as a Foreman in a leather shop. Dudley Seymour Robinson enlisted on February 16, 1916 and sailed to England where he became an Acting Sergeant but injured his left knee while training. A torn meniscus kept out of the trenches, he was discharged from the army on Dec. 17, 1916 and sailed on the troop ship Metagama back to Canada, arriving in St. John, New Brunswick on Christmas Day 1916. He married Gladys Elsie Moffat in Toronto, Ontario, on October 6, 1920, when he was 28 years old and they lived in an apartment on Silverbirch Avenue. His mother Rosina Alice passed away at home 10 Austin Avenue on November 9, 1922, at the age of 55 from pneumonia. After his mother’s death Dudley Robinson moved to Detroit and died at the age of 70 in March 1963 in Michigan, USA.

14 Austin Avenue

William Edward Harrold was born in March 1873 in Monkton Combe, Somerset, England, his father, William, a wheelwright, was 54 and his mother, Amelia Ann, was 29. Though in 1871 the family owned their own home and even had a servant, Ten years later family was destitute and he was educated in a pauper school. In 1881 his father was in the Poor House as a pauper, as was William and his brothers, Alfred and Henry, but there was no sign of his mother. His father died in 1887. In 1890, at the age of 17, he immigrated alone to Canada. He was related to the Billing family, another Somerset family, for whom Billings Avenue is named. William Harrold married Ellen Sophia Eva Cox on June 15, 1897, in Toronto, Ontario. They had two children during their marriage: Alfred William Badgerow Harrold and John E Harrold. He died at home 14 Austin Avenue on November 11, 1936 of heart disease. Though he spent his working life in a foundry, his death certificate lists his true vocation: musician.

The Wheelwright’s Arms pub in Monkton Comb, now part of the City of Bath, was likely the family home of the Harrolds. To see photos of the pub go to: https://the-wheelwrights-arms-gb.book.direct/en-us/photos

17 Austin Avenue

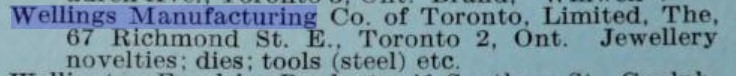

Every family has stories and secrets. We don’t know why 17-year-old Kate Wellings mysteriously left home, alarming her parents. But perhaps the numerous articles about the Wellings family might hold a clue. My sympathies are with Kate. I was a teenage daughter of a man with some “unique” ideas, obsessed with politics and who wrote numerous Letters to the Editor. I was sometimes proud of him and sometimes embarrassed. Perhaps Kate felt the same or perhaps there was another reason.

The Wellings family were the first to live at 17 Austin Avenue and built the house there where Katherine “Kate” Wellings was born on January 31, 1887, but their story, like every family’s, goes back further.

Father George Washington Wellings was born in 1855 in Birmingham, England, the centre of Britain’s steel industry. His grandfather had been a blacksmith. His father, George Wellings Sr., was a “steel toy maker”. However, at the time, “toys” were not the playthings we think of today, but the term meant small metal items like buttons and buckles, and was part of the jewelry trade.

In 1830 Thomas Gill described the production of steel jewelry in Birmingham, from cutting the blanks for the steel beads or studs, to final polishing in a mixture of lead and tin oxide with proof spirit on the palms of women’s hands, to achieve their full brilliance. Gill comments: No effectual substitute for the soft skin which is only to be found upon the delicate hands of women, has hitherto been met with.” — from Revolutionary Players Making the Modern World, published by West Midlands History at https://www.revolutionaryplayers.org.uk/birmingham-toys-cut-steel/

George Sr. also worked as a gun maker during the 1850’s and 1860’s. This was a lucrative business during that period. Between 1855 and 1861, Birmingham made six million arms most went to the USA to arm both sides in the American Civil War. Not long after George Wellings Sr. father retired from gun making and opened a pub, The Wellington, in the Duddeston at 78 Pritchett Street. German aircraft bombed the area heavily in World War. The pub no longer remains.

For more about Birmingham’s gun making history go to: http://www.bbc.co.uk/birmingham/content/articles/2009/02/18/birmingham_gun_trade_feature.shtml

George Jr. became a jeweller specializing in engraving on gold.

George Washington Wellings married Anna Maria Johnson in 1875 in Birmingham. They and their five children immigrated to Toronto in 1884. They would have seven more children, all born in Toronto.

Walter was their first child born in Canada – at home 13 Munro Street. Dr. Emily Stowe delivered the baby. Florence was born at home 17 Austin Avenue in 1889 and was soon joined by sister Hilda Marie was born on October 4, 1891. Harold was born on July 14, 1893. Another son Howard George was born on January 1, 1896, but died two years later on March 21, 1898. Irene Wellings was born on September 18, 1897.

In 1896 George Wellings ran for Alderman for the first time and was beaten badly by brick manufacturer John Russell.

Wellings a proponent of the ideas of Henry George, popular at the time, but still on the fringes. For more about the Henry George Club, go to:

http://www.dollarsandsense.org/archives/2006/0306gluckman.html

or

http://henrygeorgethestandard.org/volume-1-february-26-1887/

A tireless activist, George Wellings persevered. In the days before social media, Letters to the Editor had to fill the need for expressing political ideas.

Unsuccessful in his attempt to enter municipal politics as an Alderman, in business George Wellings prospered, renovating his home at 17 Austin Ave and building a new factory downtown on the site of his previous manufacturing plant.

Katherine “Kate” Wellings married Albert Edward Ward in Toronto, Ontario, on November 13, 1911, when she was 24 years old.

Wellings Manufacturing Company continued to proper, turning out buttons, badges, etc., what were known as “toys” in Birmingham in the mid-nineteenth century. Many thousands of Wellings cap badges, buttons and medals went overseas on the uniforms of Canadian soldiers during World War One.

Kate’s husband died of a heart attack on January 8, 1927 at their farm on the 3rd Line West, Chinguacousy, Peel, Ontario.

George Washington Wellings passed away on May 31, 1930, in Toronto, Ontario, at the age of 75. Though he tried and tried again, he never succeeded in becoming a Toronto alderman.

Katherine Wellings married James Templeman in York, Ontario, on March 27, 1937, when she was 50 years old. Both were widowed. Katherine was living at 17 Austin Avenue at the time of her marriage. James Templeman was a truck driver from Todmorden Mills. Her mother Ann Maria passed away on April 12, 1938 at her son-in-law’s home on Oakdene Crescent. Kate Wellings died in 1960 when she was 73 years old. She is buried in Mount Pleasant Cemetery. 67 Richmond Street East is now a Domino’s Pizza take-out.

To see all of this large table drag the bar below across. The table shows who lived where and when on this part Austin Avenue from 1887 when the street was born to 1921. The 1888 City Directory was based on 1887 date and there were no street numbers as it did not get mail delivery. Postal service required numbers. Joanne Doucette

| 1888 City Directory | Lot # Subdivision 549 | # | 1889 Directory | 1890 Tax Assessment Roll Occupier | 1890 Tax Assessment Roll Owner | 1890 Directory | 1891 Directory | 1894 Directory | 1895 Directory | 1900 Directory | 1903 Directory | 1904 Directory | 1905 Directory | 1906 Directory | 1907 Directory | 1912 Directory | 1919 Directory | 1921 Directory | 1921 Census |

| North | |||||||||||||||||||

| Vacant lots | 3 frontage on Pape | 2 | Vacant lots | Gray Walter, grocer | Gray Walter, grocer | Gray Walter, grocer | Gray Walter, grocer | Gray Walter, grocer | Hannigan & Gunn, grocers | Best Wilbert E | Wells George A, Hardware | ||||||||

| Vacant lots | 3 | 4 | Vacant lots | Lowman Charles | Lowman Charles E | Lowman Edwin C | Pettit John E | Pettit John E | Pettit John E | Pettit John E | Burkholder Albert/Pettit John E | King Samuel | Bowins Henry | Greenslade Louisa Mrs | Greenslade Louisa | ||||

| Vacant lots | 3 | 6 | Vacant lots | Perkins Charles E | Fortier William J | Overdale Christian S | Overdale Christian S | Overlade Pauline Mrs | Overlade Pauline Mrs | Mundy William | Mundy William | Vacant | Bruce Charles | Bruce Charles | Bruce Charles | ||||

| Vacant lots | 3 | 8 | Vacant lots | Field Emma G | Farmery Charles | Booth Albert | Booth Albert | Booth Albert | Halliburton James | Pettit William H | Pettit William H | Brittain Rev David | Hodge Mary Mrs | Hodge Mary Mrs | Hodge Mary | ||||

| Vacant lots | 3 | 10 | Vacant lots | Vacant | Cosgrove John J | Mulheron Mrs Sarah | Turner Joseph | Robinson Frederick | Robinson Frederick | Robinson Frederick | Robinson Frederick | Robinson Rose Mrs | Robinson Rose Mrs | Robinson Rose Mrs | Robinson Rose | ||||

| White Henry | 3 | 12 | White Henry | White Henry | White Henry | White Henry | Jarrett George | Doxsee George W | Vacant | Crawford Walter L | Crawford Walter L | Crawford Walter L | Montgomery Norman H | Montgomery Norman H | Montgomery Norman H | Nicholson John | Macdonald Wm | Ireland Louis | Ireland Lewis |

| Vacant lots | 3 | 14 | Vacant lots | Private Grounds | Vacant | Kordell George H | Liley Henry | Taggart Thomas R | Montgomery Norman H | Stewart William H | Stewart William H | Stewart William H | Harrold William E | Harrold William E | Harrold William E | William Harrold | |||

| Vacant lots | 3 | 16 | Vacant lots | Private Grounds | Vacant | Stewart William | Simmonds Alfred | Simmonds Alfred | Murphy John | Ridley Joseph | Ridley Joseph | Ridley Joseph | Ridley Joseph | Ridley Mark | Ridley Joseph | Ridley Joseph | |||

| LANE | A LANE | ||||||||||||||||||

| South | |||||||||||||||||||

| Vacant lots | 4 frontage on Pape | 1 | Vacant lots | Store, s e | Store, s.e. | ||||||||||||||

| Vacant lots | 4 | 3 | Private Grounds | ||||||||||||||||

| Vacant lots | 4 | 5 | |||||||||||||||||

| Vacant lots | 4 | 7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Vacant lots | 4 | 9 | |||||||||||||||||

| Vacant lots | 7 | 11 | |||||||||||||||||

| Vacant lots | 7 | 13 | |||||||||||||||||

| Vacant lots | 8 | 15 | Unfinished house | Taylor Edward | Clifford C H | Taylor Edward S | Taylor ES | Clifford James | Fredenburg George A | Clifford Caroline Mrs | Clifford Caroline Mrs | Clifford Caroline Mrs | Clifford Caroline Mrs | Clifford Caroline Mrs | Clifford Caroline Mrs | Clifford Charles | Clifford Charles | Clifford Charles | |

| Vacant lots | 8 | 17 | Wellings George | Wellings George | Wellings, Annie M. and George Wellings | Wellings George | Wellings George | Wellings George | Wellings George | Wellings George | Wellings George | Wellings George | Wellings George W | Wellings George W | Wellings George W | Wellings George W | Wellings George W | Wellings George W | |

| Private Grounds | Private grounds | ||||||||||||||||||