By Joanne Doucette, January 25, 2025

For the story of the Maple Leaf Forever Tree and some links to more information, scroll to the end of this post.

Alexander Muir (1830-1906) was Leslieville’s most famous resident, yet now few know much about him. His The Maple Leaf Forever is now rarely sung. Alexander was born April 5, 1830 in Scotland, son of John Muir, a schoolmaster, and Catherine McDiarmid, a widow. In 1833 the Muirs came to Canada. Alexander Muir grew up in Scarborough where he attended his father’s log-cabin school. Alexander Muir became a teacher too. He graduated from Queen’s College, Kingston, in 1851. He taught in Scarborough from 1853 to 1859.

Muir was, from early on, a leader in the Orange Lodge. All his life, Alexander Muir served as the Master of Ontario L.O.L. No. 142 in Toronto: “his talents were generously given where necessary to assist the Order.”[1]

His claim that good Orangemen did not hate Catholics, only the Catholic Church, would not have been accepted by many Catholics, then or now:

Orangemen bear no hatred to poor deluded Roman Catholics, but against the principles of Popish Priestcraft, and that it was the duty of every Orangeman to assist Roman Catholics when in distress, and to try and raise them up from groveling in the dust of superstition and ignorance, to a more exalted station in the scale of human beings.[2]

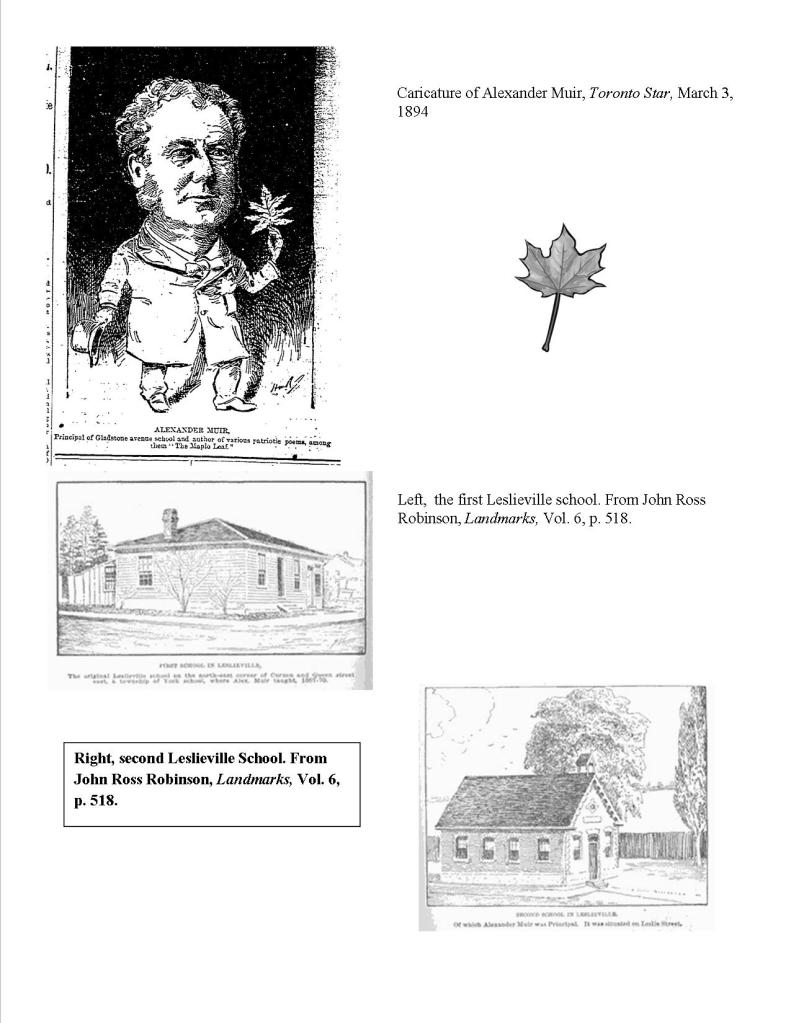

In 1860 Alexander Muir married Agnes Thomson and began teaching in the small school next to George Leslie’s general store. The same year Muir began teaching in Leslieville, Edward, Prince of Wales, toured Canada. The Maple Leaf was first used as an official emblem of Canada during his visit. The Muirs moved into a roughcast cottage neext to the Tam O’Shanter Inn. Muir did not believe in hitting his students. George Lesle hired Muir to replace a brutal teacher at Leslieville’s small frame school at Curzon and Queen (a gas station is there today). Muir became the principal, from 1863 to 1870, and moved to Leslieville’s new school. It was a typical rural Ontario schoolhouse, made of local red brick. It was at the southwest corner of Leslie Street and Sproatt Avenue.

Alex Muir was “a magnificent specimen of manhood, tall, robust, and every inch an athlete”.[3] Muir’s neighbour Greg Clark, recalled: “He was…a tall man with a large, rugged, creative head who walked leaning forward as if into a high wind.”[4] He could high jump over six feet, and hop, skip and jump up to 45 feet. One of his favourite games was quoits (horse shoes), but he excelled at other sports. He was every inch a manly man and an unusual teacher:

As I attended his school for three winters, I have vivid recollections of his manners and methods of teaching, and many a fact of useful importance to me in after life was first received from Alex Muir. He was to us boys and girls a continual surprise from his original ideas, and looking backwards after forty years, I can clearly see how advanced he was above his fellows, towering in his individuality.[5]

Muir apparently had a eidetic memory: “They used to say he could take a book, read a page or two, then reel off from memory every single word he had read.” [6] Even more unusual was Muir’s disciplining of students. He neither strapped his students with a leather belt nor whipped them with a birch rod. Corporal punishment was expected by parents and students, but too often it was a license for brutality: The bigness of Alexander Muir stood out above all else in that old school; bigness of frame, of voice, of character. These were the traits that made the boys fear and love him. He was not a whipper. The boys did not know what it was to have Alexander Muir thrash them. [7] Additionally Muir did not tolerate bullying.

Unlike most teachers of his time, Muir was not content to have his students learn by mere rote. He involved them in experiments, took them into the countryside on walks and challenged them to grow mentally and physically.

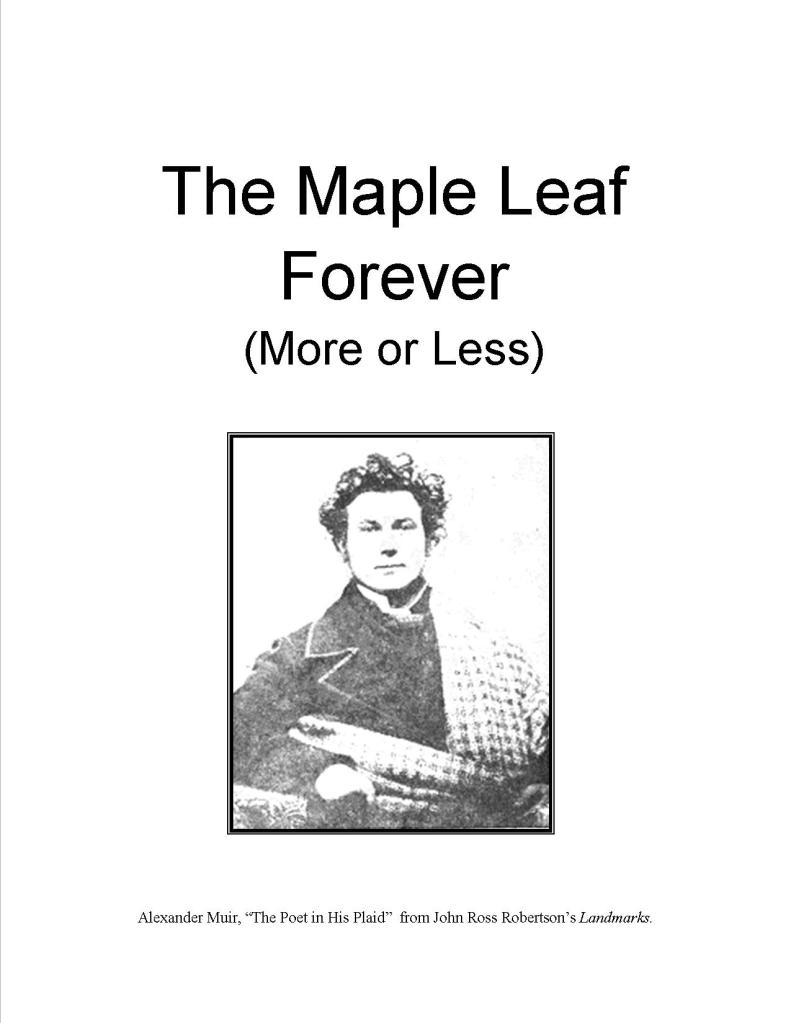

After 1863 the Muirs lived in a cottage built in 1853 by Charles Coxwell Small at the northeast corner of Queen Street East and Pape. William Higgins, retired high constable of Toronto lived on the west end of the double cottage. The Muirs occupied the east end. The large elm tree in front had a lower branch that bentg out across the road. (This Hanging Tree was, according to local legend, used for lynching criminals.) Later, in 1869 the Muirs moved to a house on Eastern Avenue. Alexander and Agnes Muir had two sons, James Joseph and George, and a daughter, Colinette Campbell. In 1864, after only four years of marriage, Agnes Muir died. In 1865, Alexander Muir married Mary Alice Johnston from Holland Landing. They had one son, Charles Alexander, and one daughter, Alice Agnes.[8]

During the Fenian raids, Alexander Muir volunteered as a private in the 2nd Battalion of Rifles (Queen’s Own Rifles). He was a member of the Highland Company. He fought in the Battle of Ridgeway on June 1, 1866. (While Muir may have fought in the Northwest Rebellion and been wounded in action, there is as yet no evidence to support this.) He left the Queens Own Rifles in August, 1867. He became a founding member of the Army and Navy Veterans Society and was a member until he died. Muir was president of the Veterans from 1892 to 1896. He was official bard for the Militia Veterans of ’66.

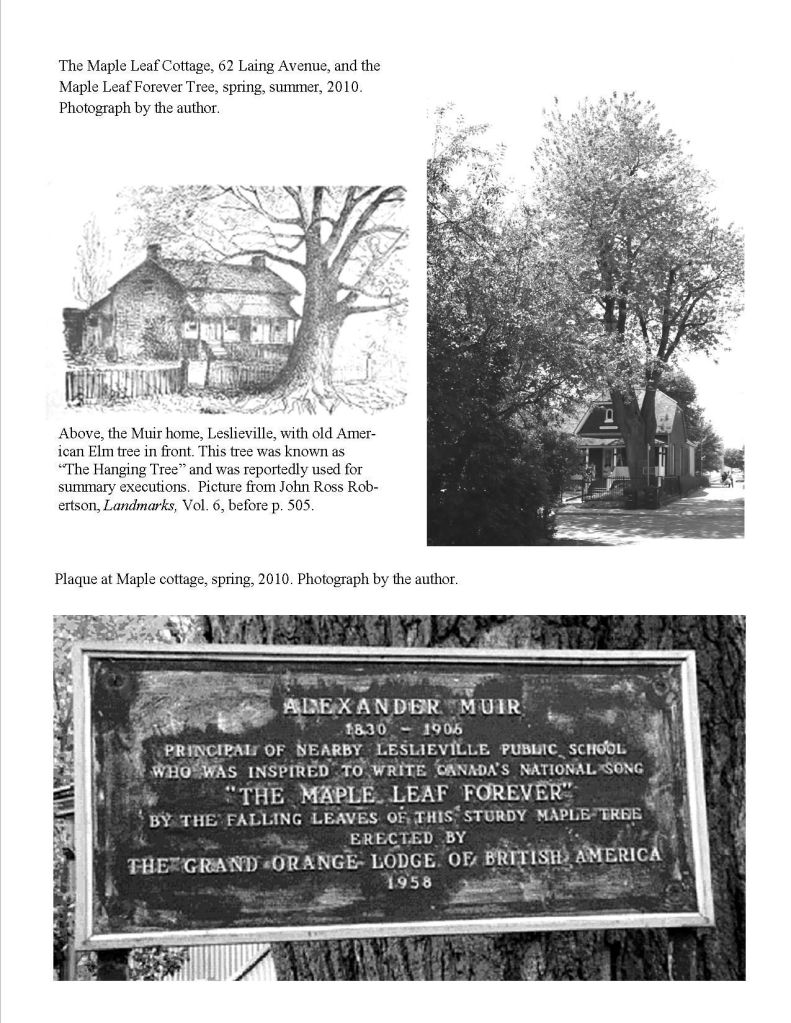

Alexander Muir left Leslieville in 1870 and went to Yorkville’s Jesse Ketchum School. Muir taught there from 1871 to 1872. Alexander Muir went to Newmarket in 1872 to be principal there. In 1874 Alexander Muir went to Holland Landing and then Beaverton. He returned to Toronto and taught at Gladstone Avenue Public School from 1888 to 1901. From 1890 to 1906 Alexander Muir was principal there. On June 26, 1906 he died while still teaching. He was 76. School children wept. His own students, numbering over 800, wore maple leaves pinned to their jackets and dresses to honour him. The School Board honoured him by renaming his last school Alexander Muir Public School.

The Song

The silver maple and Maple Cottage on Laing Street are the best-known historic sites in Leslieville. Oral tradition has Muir standing under a maple tree in front of his cottage on Laing Street when a maple leaf floated down and landed on his coat, inspiring the song.[9] Yet there are troubling inconsistencies. Maple Cottage was built in 1873 after Muir wrote the song and after the Muirs had left Leslieville. Moreover Muir never lived on Laing Street.

The Muir family has a different story. John Ross Robertson interviewed Muir’s widow, Mary Alice, in 1909, a few months after the poet’s death. She said that her husband was walking with George Leslie:

…near the Leslie nurseries, which were on the south side of the Kingston road, opposite the Muir dwelling [at Pape Avenue], one day in the autumn of 1867. A small autumn-tinged maple leaf fluttered from a tree on to Mr. Leslie’s coat sleeve. He tried to flick it off, but the little leaf still clung to his sleeve. Picking it off to throw it away, he was struck by the beautiful coloring, and called it to the attention of the friend. Knowing Mr. Muir’s literary ability, the friend, Mr. George Leslie, said, “You have been writing verses; why not write a song about the maple leaf?” [10]

Only two hours later Alexander Muir read the poem to George Leslie in the Leslieville post-office and general store. It was the custom for men to gather every day at 4 o’clock around the stove in their general store. Here they told stories while eating cheddar and crackers, washed down with scotch whiskey.[11] Muir read the poem to Mary Alice and the Muir children the next day. Mary Alice suggested that he put the words to music so that “The Maple Leaf Forever” could be sung. Muir composed the melody himself. In 1933 George Muir said: From 1864 to 1869 we lived in Leslieville at the corner of Pape Ave. and Queen St. He wrote the Maple Leaf in 1867, when I was seven years old. I remember the morning after he composed it— although he may have been some time at it before that—he was talking with my stepmother about it.’[12] George Leslie Jr.’s account was published in the East Toronto Standard:

… I was postmaster of the Leslieville Postoffice, Kingston Road, now 1164 Queen street east. It was quite a usual thing for Mr. Muir to drop into the office a half hour or so before school time to have a peep at the newspaper and have a little chat on the current events of the day. On one of these occasions, two days before Hallow E’en, I noticed an advertisement of the Caledonian Society of Montreal offering three prizes of $100, $50 and $25 for the three best Canadian patriotic songs or poems to be read at the meeting of the society on the coming Hallow E’en night.

I drew Mr. Muir’s attention to the matter and said: “There you are, Alec, you are a poet, there is your chance for glory and a little of the useful ‘rhime’. Mr. Muir was decidedly impressed with the idea, but feared the time was so short that he could hardly compose anything of merit, mail it, and expect it to reach the Society in time to be in the competition. However, with a little persuasion on my part, he came to the conclusion to make the effort. Then came the question as to the patriotic subject or motto to be chosen for the poetic effusion. This was not very easy to decide upon, and in the course of conversation we drifted out upon the sidewalk, walking slowly eastward when, after proceeding a short distance, as if wafted from Heaven, a maple leaf came fluttering downward and slighted on my left arm just below the shoulder and near my heart. Noticing it, I seemed to feel an inspired thrill and exclaimed: “There, Muir! There’s your text! The maple leaf; the Emblem of Canada! Build your poem on that.” He said: “I will,” and we parted, he for his school and I retracing my footsteps.[13]

The Southam family lived in Maple Cottage from the 1920s. They probably were the main source for the urban myth about Maple Cottage and the Silver maple there. Their version was printed in the newspapers in 1937 when the Men of the Trees placed a plaque on the old silver maple:

The story goes that returning from a walk, accompanied by his pupils, Alexander Muir, then principal of the Leslieville School, sat down in the shade of this maple to rest. Blown by the breeze a handful of maple leaves showered the school teacher and inspired the writing of the song adopted as Canada’s national song. The maple tree which was to make history shades the lawn fronting “Maple Cottage,” the home of Mrs. F.M. Southam, 62 Laing Avenue. [14]

Laing Street was not an obvious site to capture fame or attention. The street was named after William Laing. Leslieville’s “water” rats lived on Laing and nearby Lake Street (now Knox Avenue). These fishermen, icemen and others depended on Ashbridge’s Bay for a tenuous living. Their way of life came to an end when the THC filled in the bay and marsh. Some, like the Southams, were displaced from Fisherman’s Island by the Harbour Commission’s improvements. Though the Southam family claimed to be the descendants of the Boultons of the Family Compact, they were not affluent. Leslieville was a bastion of the Orange Orde. There was a living candidate available as a monument to Leslieville’s only famous man — and only famous Orangeman. The myth of Maple Cottage and its tree began to appear in the press. In 1937 in a public ceremony a plaque was placed on the tree at twilight. Mrs. Robbins, wife of Mayor William D. Robbins, a strong Orangeman, unveiled the plaque. Mayor Robbins led the July 12th Orangeman’s Parade that year. Mrs. Robbins had been a pupil of Alexander Muir at Gladstone Avenue School.[15]

The plaque was sponsored by the Men of the Trees. This organization was composed mostly of veterans. It promoted growing street trees and reforestration. The Men of the trees sought out Toronto’s finest specimen trees: the oldest, the biggest, and the most historically important trees. Not only did people admire the huge Maple Leaf Forever Tree, but Mrs. Southam gave baby maple trees, grown from seeds of the tree, to those attending. These included Mrs. Hills, Regent of the Alexander Muir Chapter of the Imperial Order of the Daughters of the Empire (I.O.D.E.). James Muir, the youngest son of Alexander Muir, was there. He signed copies of his father’s song. He did this usually for money to supplement his social assistance. Life on welfare was rough in the Great Depression.

In 1952 Mamie and Babe Southam Francis spoke to Globe and Mail reporter, Margaret Mackey. The Southams believed that the old silver maple in front of their cottage was the very tree that inspired Maple Leaf Forever.[16] However, Laing Street is eight blocks east of Pape and Queen where the Muir family said the poet found his inspiration. Why would an urban myth like this gain such widespread acceptance?

When the Southams were young, a new Canadian identity was emerging: Canadian, but distinctly Orange: …a genuine national sentiment and national unity. Were not Canadians descendants of the “Aryan tribes” of the German forests who had given Western civilization its superior systems of law and government, and who had been historically the dominant races?…The Northmen of the New World”[17]

“The Maple Leaf Forever”, reflected these attitudes, and became English Canada’s unofficial national anthem. In 1898 well known journalist J. W. Bengough said: We have at least really and truly got a national song. Good Alex Muir has done the business. The song has come, and come to stay.[18] English Canada was developing of what it meant to be Canadian, as distinct from being British. Many promoted the Maple Leaf for a new Canadian flag and the Maple Leaf Forever as the national anthem. Moreover, the Orange Order championed Muir, its own man.

Soon Canada had a new flag. The Red Ensign had a maple leaf was emblazoned on a shield on a crimson background with the Union Jack in a corner. In 1892 the Canadian Red Ensign was declared to be the official flag of Canadian merchant ships and other sea-going vessels. The 1890s were a period of intense conflict between Quebec and Ontario, Francophones and Anglophones, Catholics and Protestants. The Manitoba School Crisis heightened tensions. The Protestant Protective Association, a radical anti-Catholic secret society, moved into Ontario from the U.S. and rapidly gained political strength. Meanwhile Alexander Muir had become a celebrity. At public events English Canadians stood to their feet to sing the “Maple Leaf’ and “God Save the Queen.” Muir took part in political rallies in support of the Anglo-Canadian (and Orange Order) position on the Manitoba Schools Crisis: It is safe to say that no occupant of the platform made a bigger “hit” with the feminine portion of the audience than the kindly old gentleman, Alexander Muir, who beamed through his glasses on the audience as his “Maple Leaf” was being rolled out.[19]

Muir changed the words from time to time. Here are the words of 1896:

The Maple Leaf, Our Emblem Dear.

In days of yore the hero Wolfe, Britain’s glory did maintain

And planted firm Britain’s flag, On Canada’s fair domain,

Here may it wave, our boast, our pride, And joined in love together,

The Thistle, Shamrock, Rose entwine The Maple Leaf forever.

CHORUS.

The Maple Leaf, our emblem dear, The Maple Leaf Forever!

God save our Queen and heaven bless The Maple Leaf forever!

On many hard-fought battle fields, Our brave fathers side by side,

For freedom, homes and loved ones dear, Firmly stood, and nobly died;

And those dear rights which they maintained. We swear to yield them never!

We’ll rally ‘round the Union Jack, The Maple Leaf forever.

CHORUS.

In Autumn time our emblem dear, dons its tints of crimson hue;

Our blood would dye a deeper red, Shed, dear Canada, for you!

Ere sacred rights our fathers won, To foemen we deliver,

We’ll fighting die, our battle cry, “The Maple Leaf forever!”

CHORUS

God bless our loved Canadian home, Our Dominion’s vast domain:

May plenty ever be our lot, And peace hold endless reign;

Our Union bound by ties of love, That discord cannot sever,

God bless our loved Canadian home, Our dominion’s vast domain:

May plenty ever be our lot, And peace hold endless reign;

Our Union bound by ties of love, That discord cannot sever,

And flourish green o’er Freedom’s home, The Maple Leaf forever.[20]

By 1900 the Maple Leaf was widely recognized as the symbol for Canada. Sir Donald Smith, M.P., asked Parliament to get a better Canadian flag. He felt that the Red Ensign was cluttered with the Union Jack and a coat of arms. Most Members of Parliament wanted a flag with the Maple Leaf. Lady Aberdeen, the Governor General’s wife and an influential woman in her own right, was in favour. The Hamilton Spectator said:

GIVE US THE LEAF. Almost every little one-horse revolutionary republic in the western continent has …[a] star on [their] flag. The maple leaf forever. The Montreal Witness approved of the idea of a distinct Canadian flag “and says that one emblem should be used to the exclusion of all others, and believes that the maple leaf is by all odds the best emblem for the flag.[21]

But the road would be long and proverbially rocky. Canada did not have its own official flag until 1965 when the country adopted a red and white design with a big maple leaf.

The Secret Underground Hymn of the Anglo Resistance Movement

The Sentinel, an Orange Lodge publication, on the death of Alexander Muir, July 3, 1906, wrote:

Worshipful Brother Muir was a staunch advocate of loyalty to the British Crown and Protestant principles. He was a familiar figure at patriotic demonstrations and public celebrations, where he took a prominent part in the programme. He was a man of magnificent physique and matchless eloquence. The many occasions at lodge banquets and other public assemblies where he thrilled his audiences with a recital of the encounter at Hart’s River in South Africa when our brave Canadian boys were inspired to glorious deeds by ‘The Maple Leaf Forever’ will never be forgotten by those who had the privilege of being present.’ [22]

Most of Ontario’s population, and certainly most of Leslieville, were Protestant, English-speaking, and unselfconsciously imperialistic. They did not question their right to supremacy over Catholics, Francophones, Quebec, and “foreigners”. Catholics were long regarded as having divided loyalties, owing allegiance to the Pope before Queen and country. Many, particularly Orangemen, believed Catholicism irreconcilable with democracy. They considered bishops to be authoritarians who manipulated their flock to block progress and subvert Canada. Education was a solution to the Catholic/Francophone problem. If all children went to public schools, they could be taught English, reading, writing, and arithmetic, but also loyalty Crown and Empire. This would assimilate the Irish, the French and everyone else, except the First Nations. Aboriginal people were believed to be doomed to extinction anyway, but just in case the residential school system was designed to assimilate them too.

Neither tolerance nor multiculturalism were the foundation of Canada, as is sometimes claimed today. Multiculturalism was a concept of the 1960s, promoted by Pierre Eliot Trudeau. The Anglo-Scottish majority of Ontario in the nineteenth century wanted a country that reflected them. They saw themselves as Canada, but that world is gone. The Maple Leaf Forever has rarely been sung since the 1960s. It imperialist and pro-British text (and some would argue racist subtext) no longer fit a multicultural Ontario. In 1991 Michael Valpy wrote that Alexander Muir was forgotten along with the Maple Leaf Forever: The song eventually became a national embarrassment. It disappeared from schools, was never heard in public, was joked about by anglos as the secret underground hymn of the anglo resistance movement.[23]

Even Orange historians now acknowledge that the Maple Leaf Forever Tree in Leslieville has nothing to do with the song – other than the fact that it is an old maple tree. The Roughian speculates that, by 1930, this particular maple tree was likely to have been the only really old silver maple standing in that part of Leslieville. In short, it was the only candidate left that could have been around to drop a leaf in 1867. [24] Most of the trees along Queen Street were cleared with the street was widened. In the 1920s most of the Toronto Nurseries, where Muir and Leslie were walking, was cleared, leveled and graded for housing. Alhough far to the east of the Toronto Nursery grounds, this silver maple was the sole survivor and, therefore, a candidate for myth.

By the 1930s when the Southams were promoted their Silver maple on Laing Street, those who could actually remember the writing of “The Maple Leaf Forever” were dead.

By the Great Depression the song itself was in trouble. The Maple Leaf was losing grounds to a rival: Inroads on the dominance of this song have been made by “O Canada,” which had its birth in the Province of Quebec, but whose more general adoption has been hindered by disputes over rival English versions and translations.[25] In 1933, the body of O’Canada’s composer, Calixe Lavallée, body was returned to Canada for re-interment. Lavallée spent most of his life in the US where he died in 1891. He was buried in a Boston cemetery. On July 14, 1933, he was reburied in the Cote des Neiges cemetery on Mount Royal in Montreal after lying in state in Notre Dame Cathedral: The strains of the National Anthem played by massed bands rang out last night as the body was carried to the old church at the head of a long procession. In the church again the organ played “O Canada” …[26] O Canada was outpacing its rival.

In the 1940s someone stole the 1937 plaque. It was probably melted down for scrap metal. By the 1950s the song was no longer regarded as Canada’s national anthem, official or otherwise. People no longer stood to attention. They would not sing the second and third verses. The Orange Order, itself in decline, came to the rescue. On June 20, 1958 the Orange Association of Canada put its ownplaque plaque Maple Cottage, replacing the 1937 one. The Toronto Historical Board unveiled the plaque while a choir composed of children from nearby Leslie Street Public School sang the ‘Maple Leaf Forever.’ The Grand Orange Lodge of British North America plaque says: Alexander Muir 1830-1906 Principal of Nearby Leslieville Public School who was inspired to write Canada’s national song “The Maple Leaf Forever” by the falling leaves of this sturdy maple tree erected by the Grand Orange Lodge of British America 1958.

There were attempts to rehabilitate the song. In 1963 the Canadian Authors Association offered a $1,000 prize for a new set of lyrics to The Maple Leaf Forever. The new lyrics were supposed to be more inclusive, “inspiring to all Canadians, regardless of their national backgrounds.” Gordon V. Thompson, a music publisher, offered a cash prize for new lyrics, saying the old were too offensive: The first verse recounts how the English licked the tar out of the French on the Plains of Abraham and the second how the Canadians licked the tar out of the Americans at Lundy’s Lane and Queenston Heights.[27] The contest lit a firestorm in a teapot as people rallied around the old lyrics and the sentiments they expressed. After all, licking the tar out of the French and the Yankees was an old Ontario pastime. Canadian Authors’ Association president, Dr. Helen Creighton, had to defend the organization publicly for daring to suggest changing the words.

In 1968, the Maple Leaf Forever Tree was believed to be 160 years old. A January ice storm damaged the Silver maple and a large branch was downedl. A City Parks Department crew cleaned the wound in the tree and applied a dressing. The City installed a protective fence around the yard to safeguard the tree from trucks turning into Memory Lane. The song did not recover as well as the tree did. In 1980, O Canada, by Calixa Lavallée and Adolphe-Basile Routhier, became Canada’s official national anthem.

In 1981 the Toronto Historical Board placed Maple Cottage and the Maple Leaf Forever Tree on its list of Heritage Properties. The building was becoming derelict. Southam Scientific Instruments occupied Maple Cottage in 1988, but it lay vacant by 1991. Conestoga Investments Limited had bought it. They were, it was rumored, were going to tear down Maple Cottage and build a low-income housing development on the site. The neighbours objected. The property became the subject of the Ontario Conservation Review Board hearing. There were also rumors that the City was going to chop down the giant Silver maple. It was old and old silver maples are brittle, prone to spectacular car-crushing, people-flattening collapse. Neighbours and the Toronto Field Naturalists sprung to the rescue of the Maple Leaf Forever Tree. It is still here, cared for the arborists from the City of Toronto.

In 1991 Ontario’s Conservation Review Board of the Ontario Ministry met to discuss designating of 62 Laing Street, Maple Cottage. They held a public hearing. Neighbours wanted the building preserved (and did not want public housing). Joan Elizabeth Crosbie, a preservation officer with the Toronto Historical Board, outlined the historical and architectural reasons for designating the property. The chief argument was the oral tradition that credited the tree with inspiring Muir to write “The Maple Leaf Forever”. The evidence was dubious. John J.G. Blumenson, Preservation Officer, Toronto Historical Board, pointed out that the cottage was built six years after Muir wrote the song. The Board duly noted that Maple Cottage could not have had historical significance in relation to Alexander Muir or “The Maple Leaf Forever.” Despite its misgivings, it recommended designating 62 Laing Street as a historic property.[28]

In 1995 citizens asked the City to name the lane behind 62 Laing, Maple Leaf Cottage, Memory Lane. In 2000 the City began renovating Maple Cottage. It spent over $300,000 repairing and furnishing the building and another $128,000 landscaping the property and Maple Leaf Forever Park next door. In 2000, the private lane at 1307 and 1309 Queen Street East was named Agnes Lane at the request of Eastend Developments. Developer Nancy Hawley proposed that the lane commemorate Agnes Thomson, Alexander Muir’s first wife. Hawley argued that there were far too few Toronto streets named after women. Agnes Thomson Muir represented “ordinary women”. [29] Volunteers now maintain gardens around Maple Cottage as a tribute to the man and the tree an an oasis of green around the sturdy old cottage. The plaque remains, testifying to the Southan tenacity, the strength of the Orange Order and the beauty of the maple. But the tree is gone, falling in a gale on July 19, 2013.

https://ontariowoodcarvers.ca/maple-leaf-forever-tree/

https://www.yourleaf.org/maple-leaf-forever

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Maple_Leaf_Forever

[1] See http://www.geocities.com/Athens/Olympus/3472/webdoc2.htm Rough, Alex: Alexander Muir Orange and, Patriot and Poet.

[2] Globe, July 24, 1857

[3] Robertson, Landmarks,Vol. VI, 517.

[4] Columbo, John Robert, Canadian Literary Landmarks, (Hamilton: Dundurn Press, 1984), p. 206.

[5] Robertson, Landmarks, Vol. 6, 517.

[6] Globe and Mail, April 4, 1954

[7] Robertson, Landmarks, Vol. 6, 545.

[8] Later James Joseph Muir moved to Chicago where he became destitute and homeless. John George Muir became a printer with the Era newspaper in Newmarket. Colinette Campbell married Converse Kellogg, a salesman from New York, and moved there. Alice Muir, never married, moved to Whitby. Charles Alexander Muir moved further afield — to Montana.

[9] Bonis, 103-104.

[10] Robertson, Landmarks, Vol. 6, 558-559

[11] Masson, Allan. Unpublished manuscript. He was a descendant of George Leslie.

[12] Toronto Star, March 23, 1933.

[13] Robertson, Landmarks, Vol. VI, 558-559.

[14] Globe and Mail, October 26, 1937.

[15] Globe and Mail, October 23, 1937.

[16] Globe and Mail, December 2, 1952.

[17] Gagan, David, “The Relevance of Canada First” in Bruce Hodgins, ed., Canadian History Since Confederation: Essays and Interpretations. (Georgetown: Irwin-Dorsey, 1972), p. 77.

[18] Morgan, 664.

[19] Toronto Star, February 24, 1896.

[20] Toronto Star, June 6, 1895.

[21] Toronto Star, June 6, 1895.

[22] Sentinel, 1906.

[23] Globe and Mail, March 12, 1991.

[24] http://www.orangenet.org/outram/maple.htm

[25] Globe, April 5, 1930.

[26] Toronto Star, July 14, 1933.

[27] Globe and Mail, December 4, 1963.

[28] http://www.crb.gov.on.ca/stellent/idcplg/webdav/Contribution%20Folders/crb/english/toronto_laing62.pdf

[29] Kowalenko, W. (Wally), City Surveyor, Works and Emergency Services, Staff Report, January 31, 2000 to Toronto Community Council.

http://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/2000/agendas/committees/to/to000215/it048.htm