By Joanne Doucette

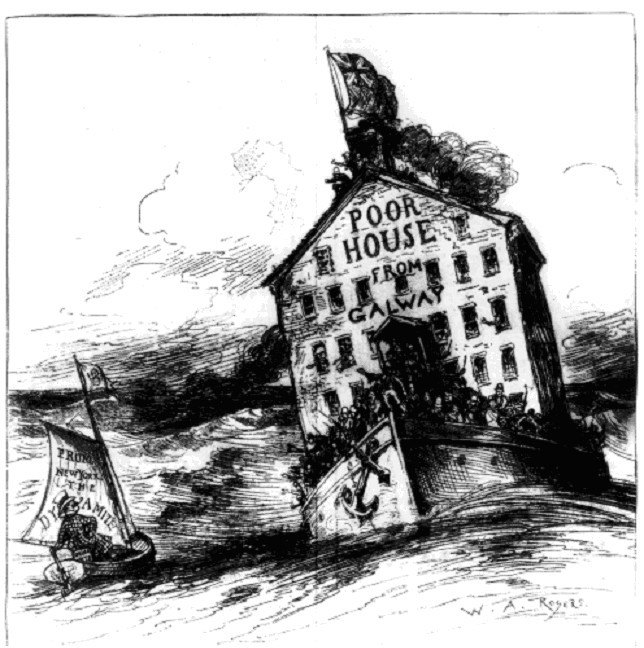

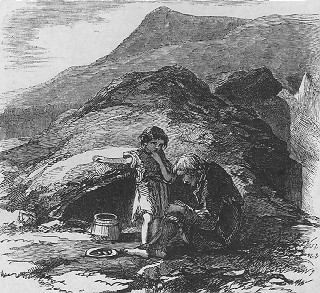

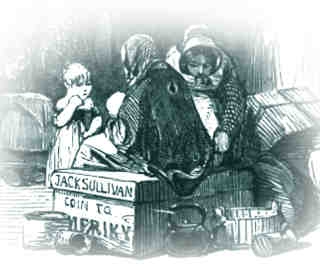

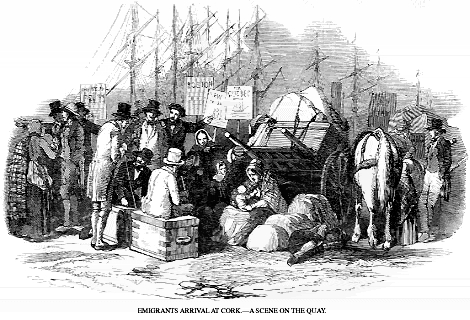

In 1845 Toronto had only 21,000 residents. In 1846 there was crop failure through Ireland. A blight, caused by an oocyte, destroyed the potato crop. “The Great Hunger” or An Gorta Mor, killed over a million people: another million left Ireland. By the end of the winter of 1847-48, 38,560 immigrants had passed through Toronto. 1,124 died. Some of these Irish immigrants landed in the suburbs around Toronto, including Ashport [became Leslieville about ten years later], where they usually became labourers.

In 1847 about 105,000 Irish emigrants left for British North America, many landing at the Simcoe Street docks. The Times of London:

[the] …quay at Toronto was crowded with a throng of dying and diseased abjects; the living and the dead lay huddled together in horrible embrace.[1]

Larratt Smith lamented:

They arrive here to the extent of about 300 to 600 by any steamer. The sick are immediately sent to the hospital which has been given up to them entirely and the healthy are fed and allowed to occupy the Immigrant Sheds for 24 hours; at the expiration of this time, they are obliged to keep moving, their rations are stopped and if they are found begging are imprisoned at once. Means of conveyance are provided by the Corporation to take them off at once to the country, and they are accordingly carried off “willy nilly” some 16 or 20 miles, North, South, East and West and quickly put down, leaving the country to support them by giving them employment….It is a great pity we have not some railroads going on, if only to give employment to these thousands of destitute Irish swarming among us. The hospitals contain over 600 and besides the sick and convalescent, we have hundreds of widows and orphans to provide for.[2]

Only those immigrants who had family or friends in Toronto or neighborhood could stay in the City; the others had to get out or be arrested, put on a wagon and dumped in the countryside. For many Toronto was just a stop on their ultimate destination: the USA. Many others walked away along the main roads: Yonge Street to the north, Dundas Street to the west, and Kingston Road to the east, seeking food, shelter and employment. Many found this in Leslieville, often working for Protestant Irish or Scottish market garden owners and brickyard owners. These immigrant Irish provided a pool of cheap labour for Ashport’s market gardens, brickyards, piggeries and ice companies.

Toronto Board of Health,

SANATORY REGULATIONS,

ADOPTED BY THE BOARD OF HEALTH,

JUNE 19, 1847.

First—That all Emigrants arriving at this Port by Steamers or other Vessels be landed at the Wharf at the foot of Simcoe-street, commonly known as Dr. Rees’ Wharf, and there only. And the Master of any Steamer or other Vessel violating this Regulation, will subject himself to the penalties prescribed by the City Law in that case, made and provided.

SECOND—That all Emigrants arriving at this Port, at the public charge except only those who come hither to join their friends or connections residing in, or in the immediate neighbourhood of this City, be forwarded to their intended destination by the very first conveyance, by land or water, which the Board of Health or the Emigrant Agent may provide for that purpose. That after the means of conveyance, as aforesaid, shall have been provided for them, no such Emigrants shall be permitted to occupy the Emigrant Sheds, or to receive the Government allowance of provisions, except only in case of sickness of the Emigrant or his family, and except in such special cases as may be sanctioned by the Board of Health.

THIRD—That provision being made for all such Emigrants during their necessary detention in the City, no such Emigrant will be allowed to seek alms or beg in the City, and anyone found doing so, will be immediately arrested and punished according to the City Laws, in such case made and provided.

FOURTH—All Tavern-keepers, Boarding or Lodging—Housekeepers, and other persons having Emigrants staying in their premises, are required to make immediate report to the High Bailiff, or other Officer on duty at the City Hall of any sick person who may be staying in their houses; and any Tavern, Boarding or Lodging-Housekeeper, who shall neglect to make such report of any sick person who may be in their premises, will, upon conviction, be fined conformably to the Law.

FIFTH—That the Medical Officer in charge of the Emigrant Hospital, be required to visit the Emigrant Sheds, morning and evening of each day, for the purpose of examining and removing to the Hospital all sick Emigrants, who may require medical treatment, and that the said officers be also required to visit all Steamers, or other Vessels which may arrive at this Port with Emigrants, immediately on the arrival of such Steamer or other Vessel, for the same purpose as above stated.

Published by Order of the Board of Health, Charles Daly, C.C.C. Clerk’s Office, Toronto, June 19th, 1847.[3]

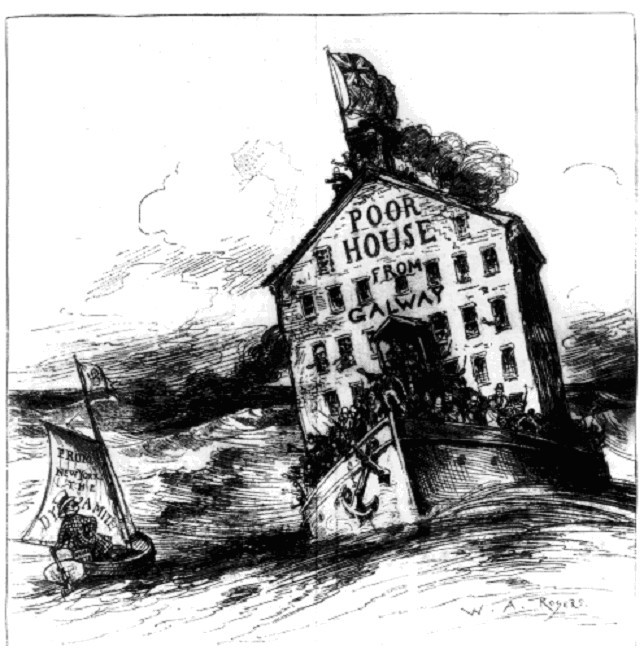

Many in Toronto and, no doubt, along Kingston Road, rallied to do what they could for the unfortunate Irish, but others were not above exploiting the situation to make money. In 1847 William H. Boulton, M.P.P. and Toronto’s Mayor, had a farm in Ashport, on Kingston Road, …very sandy in soil, 270 acres in extent, and very hard to be disposed of…” Boulton was trying to sell it but was asking a phenomenally exorbitant amount in what even then was considered a conflict of interest. He tried to sell it to the City of Toronto for £5000 pounds as a site for a new House of Industry, insisting that there really was no other suitable site. City Council declined. Boulton used scare tactics, warning of hordes of emigrant Irish to come. Still Council would not budge:

But the council were not to be humbugged—they would have nothing to do with it—they thought that the emigrants might be very well provided for in the sheds now used as an Hospital and in the Convalescent Hospital.[4]

These were not the first Irish immigrants to Toronto and area. Almost half a million Irish came to British North America before 1847. Like the Beattys and most of the other Protestant Irish who became the employers in Leslieville, these were middle class, educated people, usually with a trade and some savings. Unlike the coffin ships of Black 1847, these Irish Protestants came on sound, relatively comfortable ships. Most of them came from the north of Ireland. They, with the Scots, gave Ashport a very Celtic character. Thomas Beatty and John McLatchie typified these earlier emigrants and their children. Some had sympathy for the flood of hungry, typhus-ridden Irish; others had little, thinking of themselves more as British and certainly as Protestant, and, therefore, both more loyal and deserving. Most belonged to the Orange Lodge, an anti-Catholic, pro-British fraternal order.

Some Irish Catholics were early settlers too. The Hollands arrived in the area before the others. They had been involved in the Upper Canada Rebellion and moved here to escape possible persecution and prosecution. Daniel O’Sullivan, blacksmith and tavern owner, had also been involved with William Lyon Mackenzie. He arrived in Toronto just after the War of 1812. These early residents succeeded in their businesses and socially, putting them in a position to help the Famine refugees.

The settlers were mostly British, including English, Scots, and Irish – mostly Protestant Irish, making Leslieville and an Anglo-Celtic village with an Irish Catholic underclass. Catholicism and Irishness were seen synonymous; many Irish Protestants simply referred to themselves as “Scottish” or “British”.

By 1850 Ashport had a small, but growing middle class, including farmers, brickmakers and market gardeners. Farmers made money through subdividing their property as Leslieville grew. The village was overwhelmingly working-class with only a few more prosperous inhabitants, including the Ashbridges, Blongs, the Hastings, some brickyard owners and a few others and, of course, George Leslie, market gardener and tree specialist who bought up most of the land around Leslieville’s “four corners”: Queen Street East and Leslie Street.

Ashport became known as Leslie or Leslieville after George Leslie Junior became postmaster in 1862.[5] George Leslie Senior was known as “Squire Leslie” and was the Justice of the Peace and a major employer, as well as landowner, in Leslieville. George Leslie, a close friend of Liberal premier Oliver Mowat, was a “True Grit” and for a man of his time, progressive in most things. He allowed his private park to be used to raise money for St. Joseph’s Catholic Church. “A most successful open-air festival and picnic was held in Leslie’s grove, Eastern Avenue, yesterday in aid of the building fund of the Leslieville Roman Catholic church. A brass and quadrille band was in attendance, and a happy time was spent in athletic sports, races, etc.” They raised $150.00.[6] Like other churches St. Joseph’s hosted concerts, teas and other social events. Sometimes these were held at Poulton Hall, including a concert in April, 1893.[7] Leslie had the largest tree nursery in Canada in the nineteenth century.

Irish Catholics formed an enclave in one of Leslieville’s first subdivisions: north of Queen Street between Jones and Hastings around the Holland’s abattoir and piggery between Curzon and Leslie, north of the Kingston Road on land owned by George Leslie. The Fogartys, Finucans, Flynns, Larkins, Ryans, Kavanaughs and others lived there. Here they had small market gardens of their own, but Irish Catholics, often called “native Irish”, also took on the jobs no one else wanted. They worked for hard labour for low wages in the market gardens, cutting ice, fishing and/or making bricks. Labourers worked at a series of seasonal jobs, with no job security, no benefits, often being toiling in a brickyard during the “making season”, harvesting crops and cutting ice in the winter. Women often worked in these industries, particularly market gardening, or sometimes became servants. Working people did not put their economic security in “one basket”. The whole family worked at whatever they could find.

Though welcome to do menial labour, Irish immigrants were not entirely welcome in society. Victorian society was hierarchical, patriarchal and racist. People were expected to know their place. With hard work an ambitious Protestant might become a self-made man, but it was much harder for Irish Catholics to climb the social ladder.

The tycoons like street railway owner Frank Smith and brewer Eugene O’Keefe were exceptions However, some Leslieville Catholics (e.g., Patrick Fogarty and James Morin) did become small businessmen through hard work, enterprise and luck. Some fought their way through life with their fists like some of the Hollands and Daniel Tim Daniel O’Sullivan, a blacksmith and hotel owner from the Blacksmith Arms in Norway. He was a street brawler who served as a rough and tumble leader of the native Irish in nineteenth century Toronto and a founding member of St. Joseph’s Parish, Leslieville. Locked out of society, Catholics fought hard to build their own institutions, including schools, hospitals, insurance companies, lodges and charities. In the 1870’s Irish Catholics formed the new St. Joseph’s Parish in Leslieville. (It even had its own brass band.)

In 1841 the Catholic Church divided Upper Canada into two dioceses. The Pope gave Michael Power (1804-47) the western half of the former Diocese of Kingston. It became the new Diocese of Toronto. Michael Power, Toronto’s first Catholic bishop, was born in Halifax to Irish parents. His father was a sailor; his mother kept a boarding house. He was ordained at 23. He had several postings in Quebec before he came here in 1842 as bishop. Michael Power died on October 1, 1847, of typhus he caught looking after Irish immigrants. He was 42. His bereft diocese buried him under the altar of St. Michael’s Cathedral, still under construction. The Famine did not discriminate. Both Anglican and Catholic priests died serving the sick and dying Irish. Giving the sacraments to the dying was particularly perilous as the priest struggled to hear in the noisy Immigrant Sheds. The lice that carried typhus jumped from the dying patient to the priest as he leaned over to hear their confession or perform the last rites. The Famine and Black 47 changed Toronto and Leslieville forever.

From 1860 to 1890 the number of Toronto’s Roman Catholic parish churches increased by 40. The number of Catholics grew through immigration and a high birth rate. It was almost as if Catholics were giving birth to make up for the many lost. However, given the high mortality rate among infants and children, the more children a couple had the more chance one or two would survive to adulthood.

In 1871 Catholics built a two-room brick school on the west end of a 55-foot lot running from Curzon Street to Leslie Street on property owned by the Archdiocese of Toronto. It was next to an abattoir and a piggery, but at the heart of Leslieville’s Catholic community. At first, this new school was used for church services. Priests, including Rev. Francis Rooney, came out from St. Paul’s Church on Power Street to celebrate Mass every Sunday. On November 10, 1878, the Diocese of Toronto created St. Joseph’s Parish. It was the first Toronto parish east of St. Paul’s. In 1878, Catholics began working to fund and build a new brick church. The architects were Kennedy, McVittie and Holland. The church was to be built between Curzon and Leslie Street

The priest at this new St. Joseph’s Church for most of its early days was Michael McCartin O’Reilly (1842-1893). O’Reilly was born at Granard, County Longford, Ireland, in 1842, He entered St. Mel’s Day School in January 1860 and left in 1862 for the Toronto Mission.[8] He studied philosophy at St. Michael’s College, Toronto, and theology at Niagara Falls and Montreal. Bishop Lynch ordained him in 1866 and he was sent to St. Mary’s Church, on Bathurst Street, as assistant. O’Reilly served in various parishes, including Brock, St. Catharines, Thorold, Stayner and Uxbridge. In June, 1878 he took charge of the new parish of St. Joseph and later founded the parish of St. John further east on Queen Street. He died on January 17, 1893 and was buried under the altar of St. Joseph’s Church. Robertson, an Orangeman if ever there was one, said of O’Reilly, that he was:

…as popular as a man as he was as a priest. He was always welcomed wherever his business or his duties took him throughout the district, irrespective of his creed. He took considerable interest in public affairs and was also a member of the Separate School Board.[9]

Archbishop Lynch laid the cornerstone of St. Joseph’s Church on September 28, 1884. Lynch did his duty in the pouring rain, assisted by Fathers O’Reilly and Kenny. He used the same silver trowel that Bishop Power used to lay the cornerstone of St. Michael’s Cathedral in 1843. About 200 people stood in the rain to watch. They included ex- Alderman James Pape, James Walsh, Thomas Finucan, Thomas Wild, Daniel Tim Daniel O’Sullivan, Daniel Fitzgerald, Lewis Fitzgerald, John Pape, J.G. Murphy and others. The Irish Catholic Benevolent Union Band played. James Pape contributed a beautiful floral arrangement in the shape of a horseshoe. It rained and then it poured.

John Ross Robertson said of St. Joseph’s, while disparaging Leslieville’s landscape:

…is one of the prettiest features in a district which has few natural advantages, either in scenery or surroundings…The church is bright, light and airy, cool in summer and always comfortably warmed in winter. In addition to these advantages the congregations at all the services are always good, and when any noteworthy preacher occupies the pulpit, or special services are announced, it often happens that many of the would-be auditors fail to find the necessary accommodation.” [10]

Despite Orangeman Robertson’s positive notes about St. Joseph’s, all was not smooth sailing between Irish Catholics and Protestants. Almost every year, on St. Patrick’s Day, March 17, and the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne (July 12th) violence usually broke out between the Orange and the Green as one side tried to parade through the other side’s neighbourhood. Even though only rarely was anybody killed, it was nasty enough. Handguns were common and cheap; liquor was even cheaper. The police force traditionally sided on the side of the Orangemen and even participated in the riots. Eventually the whole police force was fired and replaced with a professional force under a soldier, William Prince. Many Irish Catholics came to almost trust the police after Orange mobs attacked a peaceful procession of Catholics, mostly women and children. The 1875 procession was celebrating a Jubilee Year, proclaimed by the Pope. The Jubilee Riot was probably the largest riot in Toronto’s history. To the astonishment of all concerned, the police served and protected the Catholics even though it meant a number of constables were seriously injured. The new Toronto police force was there to maintain law and order, not support misbehaving Orangemen.

Thus, it was with some trepidation (and cleaning and oiling of firearms), that both Protestants and Catholics awaited the big party Catholics planned to celebrate the birth of the Great Liberator, Daniel O’Connell. Daniel O’Connell, one of the great heroes of Irish independence, was loathed by the Orange Order. Catholic Leslieville was not to be left out of the birthday bash.

Toronto’s Emerald Beneficial Association (EBA) was widely considered a front for the Irish Brotherhood, a radical organization. Leslieville’s Emerald Band played familiar old country tunes as it led the Leslieville Branch No. 4 of the EBA along Kingston Road. They marched through Corktown and down to the docks. There they greeted the Hamilton EBA led by M. McMahon. The growing body began to form up behind Grand Marshall James Doherty. Vicar-General Francis Rooney was in the first carriage with Mayor O’Reilly of Hamilton and others. The parade got under way, marching up from the docks to the Bishop’s Palace on Church Street. The bands played Irish music all the way.

The Archbishop graciously received the parade.

From the Palace they marched to the Cricket Ground. There was music, food and a little discreet gambling. There was archery. There were also games and prizes:

- standing jump (prize box of cigars)

- running jump (bottle of champagne)

- married men’s race ($4 prize)

- running hop, step and jump (box of cigars)

- three quick jumps (bottle of wine)

- 100-yard race ($50); etc.

Of course, speech followed speech followed speech. The Emerald Beneficial Association [EBA]’s stated purpose was innocuous. It was to provide members with support and financial assistance in case of sickness or death. There was nothing about armed rebellion, overthrowing the Crown or liberating Ireland. Instead, the speakers called for friendship between Protestants and Catholics, and celebrated Canada’s freedom of religion.

After the speeches, men let a greased pig out of a box to run panicked and squealing through the crowd until captured (and roasted). After the speeches, sports and games, the Emeralds of Toronto and Leslieville marched the Hamilton contingent back down to the docks. The bands played more Irish music. The Hamilton brethren and their Mayor, James Edwin O’Reilly, sailed back home. The remaining Emeralds embarked on the steamer Prince Arthur for their midnight cruise. However, a mob of Orangemen were now crowding the dock, prepared for an old-fashioned donnybrook or riot. Obscenities flew as fast as the rocks flying at the Prince Arthur as she pulled away from her moorings. The EBA failed to arm themselves with stones and instead responded by hurling deckchairs down at their foes. The police pushed the rioters back from the steamer. As the good ship sailed beyond the reach of their rocks, the Orangemen continued to roar at the Irish Catholics. The Prince Arthur disappeared into the dark of Toronto Harbour.

About 500 anti-Catholic rioters thronged the dock. More streamed down the streets leading to the waterfront. They came from north, east and west, armed with rocks, bottles and more serious weapons. Orange banners unfurled. The police formed a thin blue line. With nightsticks at the ready, their backs were to the bay. Rocks rained down on them. At least one constable was seriously injured.

While the Emeralds were celebrating, others had been planning a much wilder party. When the Prince Arthur docked, men planned to board the steamer itself and attack the EBA. Police reinforcements poured in and the Orange mob was finally cowed. When the Prince Arthur finally returned at about 1:30 a.m., nearly everyone had gone home or to taverns to wash away their sorrows. Despite the rioting, no arrests were made. A few years later, in 1878, during the O’Donovan Rossa riots, several men were shot during a brawl in Leslieville.

Like other churches, St. Joseph’s social events involved more than marches and the possibility of riots. The parish hosted concerts, teas and other fundraisers. Benefits helped to pay off the church debts, including the mortgage. In 1880 St. Joseph’s Parish hosted a concert at St. Lawrence Hall “to aid in liquidating the debt on the parochial residence of Rev. Father O’Reilly, at Leslieville.” It was a success. The concert featured quartettes, soloists, including a piano solo of the sentimental favourite “Home Sweet Home” and, of course, Irish songs. In 1882, “A most successful open-air festival and picnic was held in Leslie’s grove, Eastern Avenue, yesterday in aid of the building fund of the Leslieville Roman Catholic church. A brass and quadrille band was in attendance, and a happy time was spent in athletic sports, races, etc.” They raised $150.00.[11] There was a concert at St. Lawrence Hall to raise funds to help liquidate the debt of Leslieville’s Roman Catholic schoolhouse. The concert featured vocal and instrumental music presented by Misses Murphy, Lynch, Carroll, and Doherty, and Messrs. Costello and Gallivan. Dancing followed the concert.

Despite the concerts and some goodwill from non-Catholics, Leslieville still was not safe for Catholics. Bullies roughed up Father O’Reilly. Even Orangemen were shocked. This was their local priest, and no one would touch him. It must have been strangers:

Father O’Reilly is deservedly respected in the neighbourhood by both Catholics and Protestants and does not deserve such treatment. It is only fair to say the young men are not residents of Riverside.[12]

By 1888, St. Joseph’s Church was finished. Bishop O’Mahoney dedicated the Church on July 18. The Rev. Dr. O’Reilly, treasurer of the Irish Land League of Detroit, gave the first sermon. One can only wonder what Leslieville’s Orangemen thought. Even then, however, things were more nuanced than a simple Green vs. Orange reading would admit. The larger community, including some Orangemen, helped to defray the parish’s debt. Fundraisers were held at Squire Leslie’s Leslie Grove. In 1898:

The fancy fair in aid in clearing off the heavy debt of St. Joseph church will open this evening in Dingman’s hall, corner of Queen Street East and Broadview Avenue [now the Broadview Hotel] and will be continued for one week. The Mayor will be present and act as chairman. The programme will consist of songs, drill, and declamations by the children of St. Anne’s and St. Joseph’s schools. There will also be a concert each evening.[13]

Following Father O’Reilly’s death, Father Bergin was pastor for several years until, in 1893, W. C. McEntee became rector of St. Joseph’s. St. Joseph’s became well known for its services, especially its musical vespers. The parish was blessed with some fine singers and a dedicated congregation.

St. Joseph’s parishioners helped St. Joseph’s not just because it was expected of them or because the priest told them that that they must. The Catholics of Leslieville had lived through a shocking, unprecedented event, the Potato Famine. There were those who had not themselves suffered from starvation since they came here before the Famine. However, their family, friends and villages had surely lived and died in that terrible time. The Famine changed how Irish Catholics, here and in Ireland, related to the Church. Most Irish Catholics before the Famine were not considered deeply religious. The harsh Penal Laws imposed by England on Ireland had restricted the practice of Catholicism and particularly Catholic education. Thus, Catholicism in Ireland was important, but not central to many people’s lives. However, after the Famine, Irish Catholics here and in Ireland turned to their Church for leadership, comfort, social services and education. By the end of the 1800’s, the Church was a central force in the lives of most Irish Canadian Catholics. The pulpit influenced every aspect of life, including how a man voted. Bishops and even ordinary priests did not hesitate to tell Catholics how they should vote. Some of the most difficult struggles with in the Roman Catholic Church in Toronto in the late nineteenth century were over the introduction of the secret ballot in the election of school board trustees. The clergy were quite direct in their instructions to the laity to oppose the secret ballot.

Catholics did not take their Church for granted. They fought for the right to vote and for their own schools. They dug deep to pay for their own social service agencies, such as the House of Providence and St. Michael’s Hospital. While they did give up the Irish language, they rallied around their faith.

In small villages it could be almost as if people were living in two separate worlds, one Catholic, one Protestant, on the same landscape with the same roads, rivers and trees. Occasionally, however, even in Leslieville, there was intermarriage between Catholics and Protestants. In 1870, even feisty brawler, Daniel Tim Daniel O’Sullivan married an Anglican. Wealthy Family Compact descendent Charles Small married a Catholic. In these cases, the children were usually raised in their mother’s faith and “lost” to the church of their father. The churches, both Protestant and Catholic, vigorously disapproved of mixed marriages.

By 1900 St. Joseph’s parish had 220 families. Most worked in brickyards, market gardens and stores. When the streetcar suburbs boomed, thousands of Catholics moved into the “Goose Flats”, as Leslieville was sometimes called. More parishes were created. However, Protestant immigrants, mostly from English cities, began to pour into Toronto in the late nineteenth century. Although Catholics grew in number from 7,940 in 1851 to 28,994 by 1901, their relative share of Toronto population fell from 25.8 per cent to 13.9 per cent.[14]

In 1907 the Separate School Board authorized constructing a new four-room school on Leslie Street just north of St. Joseph’s Church. It was expected to cost $15,000.00. In 1914 St. Joseph’s Roman Catholic Church built a new parish house. But as this caricature of Irish man with flag, Toronto Sunday World, March 17, 1912, shows the old stereotypes still held sway in what was nicknamed “The Belfast of the North”, Toronto.

[1] Coyle, Jim, “A fitting tribute, a horrific time”, inTheStar.com – News – A fitting tribute, a horrific timeToronto Star, June 19, 2007.

[2] Careless, J.M.S., Toronto: An Illustrated History (Toronto: J. Lorimer and the National Museum of Man, 1984), p. 71.

[3] Globe Saturday, June 26, 1847

[4] Globe, October 6, 1847.

[5] City of Toronto Directory for 1867-68. Sutherland. Mitchell’s general directory for the City of Toronto and gazetteer of the counties, 404. of York and Peel for 1866, p. 404

[6] Toronto Daily Mail July 25, 1882

[7] Tuesday, April 4, 1893 Globe

[8] personal communication from Fr. Tom Murray, Archivist, St. Mel’s College, Longford, Ireland.

[9] Robertson, Landmarks, Vol. IV, 341.

[10] Robertson, Landmarks, Vol. IV, 341.

[11] Toronto Daily Mail, July 25, 1882.

[12] Globe, June 5, 1882.

[13] Daily Mail and Empire, December 14, 1898.

[14] Nicolson, Murray W. “The Other Toronto: Irish Catholics in a Victorian City, 1850-1900” in Polyphony Summer (Toronto: Multicultural History Society of Ontario 1984), pp. 19-23.