Jane Ward and the Brook’s Bush Gang

by Joanne Doucette

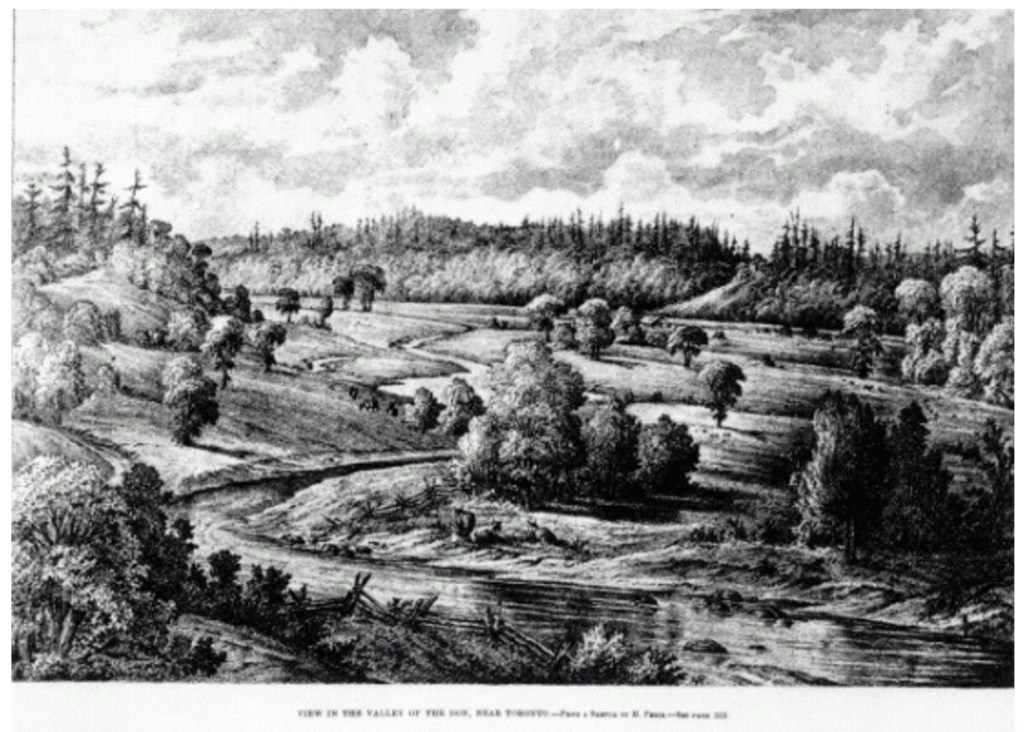

Toronto wasn’t a nice place in the mid-19th century. Who would expect it to be? The Plan of The City of Toronto listed thirty-five churches and the 1861-62 City Directory listed 221 taverns. There were also many unlicensed shanty saloons in the Don Valley in places like Brook’s Bush. There were many caves and dens along and near the Don River and its tributaries in the Riverdale area. Most sites were gone by 1900.

Henry Scadding, in Toronto of Old mentioned natural and human excavations where bears, foxes, wolves, and other animals had dens. Human excavations in the hillsides were common as early as the 1820s and later served as deposit sites for booty and loot from break-ins and robberies by the Brook’s Bush Gang and others (i.e., 1840s – 70s). Toronto had a booming red-light district, one block north of the courthouse.

Most arrests were for drunkenness; keeping brothels ranked second. Other frequent crimes were theft, passing bad money, and keeping dangerous dogs. Murders were rare. Up to 1859 there had been only eleven since Toronto was established in 1793. So how did we come to know of Emily Jane Ward, the so-called “Pirate Queen of Riverdale”, a short slight, but tough woman who lived and drank hard.

Well, she picked the wrong victim. If you are a smart robber, you don’t mess with the press and you don’t mess with influential politicians. She killed John Sheridan Hogan, a member of the provincial legislature and newspaperman. But this wasn’t the first murder she was involved in, and we know of others.

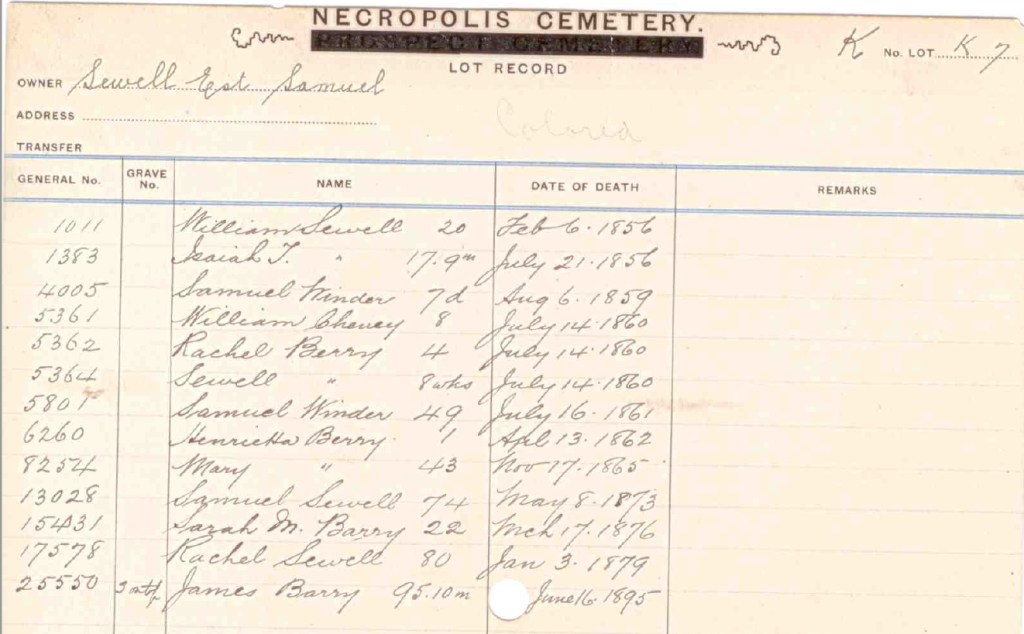

Samuel and Rachel Sewell were gardeners and breeders of horses near Logan and Queen. Their farm lane became known as “Sewell’s Lane”, and later “Logan Avenue”. Sons William and Isaiah were born in the U.S. Son Samuel was born in Ontario. While Samuel Sewell Sr. claimed to have no religion in the 1851 Census, the rest of the Family was Baptist. Samuel Sewell Sr. was born in 1797 under slavery and died May 8, 1873. He could be said to be the patriarch of Leslieville’s black community. He is buried in the Necropolis Cemetery with his family. His wife Rachel died in 1879 and is buried beside him. Son William died early at the age of 15 on Feb. 6, 1856, from scrofula or tuberculosis of the glands of the neck. Daughter Maria Sewell married Samuel Winder (Widower) on Jan. 21, 1847.

On July 21, 1856, Michael Barry (no relation to the Black Barry family) and others of the Brook’s Bush gang murdered Isaiah Sewell by bashing him over the head. The Brook’s Bush gang was a collection of prostitutes, pickpockets, thieves and petty criminals whose headquarters was an old barn in what is now Withrow Park. They were all white, mostly Irish but lead by Jane Ward, a vicious English prostitute.

Jane Ward, like most of those present, was conveniently looking the other way when Sewell was murdered. A prostitute named Catherine Cogan flirted with Isaiah Sewell. A witness said, “I heard someone say it was a shame for a white girl to be seen with a black man.” Samuel Sewell was a witness in the trial. He had sent his son to the mill road (Broadview Avenue) with money to buy hay. Isaiah was what we would call, “A good kid.” He never associated with the Brook’s Bush gang.

It was part of their modus operandi to ply a victim with alcohol and lure him with sex, and then rob him, as you will note if you go through the Time Line that I’ve posted below. Another witness testified, “[Michael Barry] never spoke to the coloured boy. The coloured boy was standing with his back to Barry. Barry never spoke when he struck the blow. The blow was given with a black glass bottle…He fell immediately, never got up, and never spoke…when the blow was struck, Barry called the deceased a black b—g—r…” The money disappeared. Michael Barry was convicted of manslaughter, probably taking the fall for the others as he himself was not a gang member, just a “newbie”. For years the Brook’s Bush gang members boasted of getting away with killing a black man. (Globe, Oct. 30, 1856)

John Sheridan Hogan was born near Dublin, Ireland around 1815 and died at Toronto on December 1, 1859. His parents sent him to York in Upper Canada to his uncle when only twelve. John worked as a printer’s apprentice at the Canadian Freeman, owned by a fellow Irish Immigrant, but at sixteen he ran away to Hamilton, where A.K. Mackenzie, owner of the Canadian Wesleyan, a new Methodist publication, hired him as a typesetter. In 1835, when the Wesleyan closed, Hogan decided to become a lawyer and articled for a Hamilton lawyer and politician Allan Napier MacNab [Dundurn Castle] as clerk-bookkeeper. When the Upper Canada Rebellion broke out in December 1837, Hogan, then 22, joined the government forces under MacNab against the rebels.

Hogan married well, but, in 1852, Hogan and his wife separated. He moved to Toronto and worked on pro-Tory newspapers as a journalist and editor. The same year, Hogan began an affair with Sarah Lawrie, a plain, uneducated, caring mother of three. Hogan founded his own weekly, The United Empire, and in 1855 became editor of Toronto’s British Colonist. That same year he wrote a prize-winning essay on Canada for the Canadian committee of the Paris Exposition. In 1856 he became editor-in-chief of the Colonist. In 1857 he was elected to the Assembly as a Reformer; he was considered one of the rising stars of the Reform Party. Member for Grey in the Ontario parliament.

Hogan had everything going for him: tall, lean, fit, and personable. He had powerful friends such as Toronto City Jail Governor George Allen and York County Crown Attorney Richard Dempsey. Among his acquaintances were John A. Macdonald and George Brown. “Hogan became one of the ablest Canadian writers of his day,” Samuel Thompson wrote in his Reminiscences of a Canadian Pioneer, published in 1883. Hogan was regarded–with Oliver Mowat, later premier of Ontario, and D’Arcy McGee–as one of the coming men among the new members. He moved into the Rossin House, Toronto’s first luxury hotel. The hotel was also near Mrs. Lawrie’s home on Bay Street and the Colonist offices.

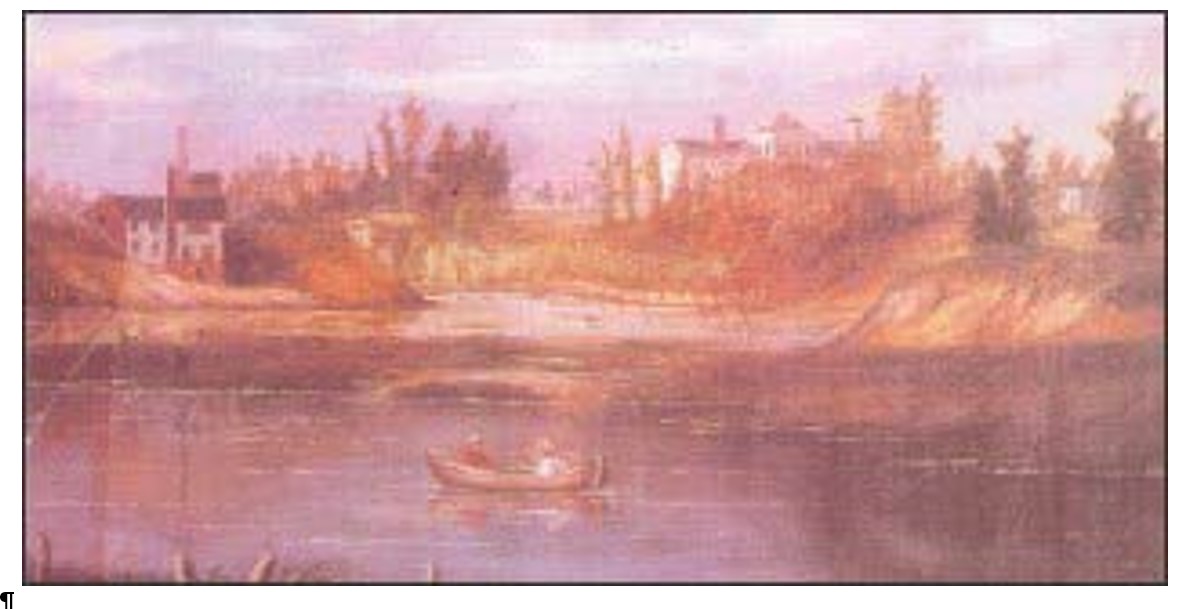

He became close friends with contractor James Beachell, warden for Grey County. Hogan often visited him at his Toronto house, Alma Cottage, on the east side of the Don River.

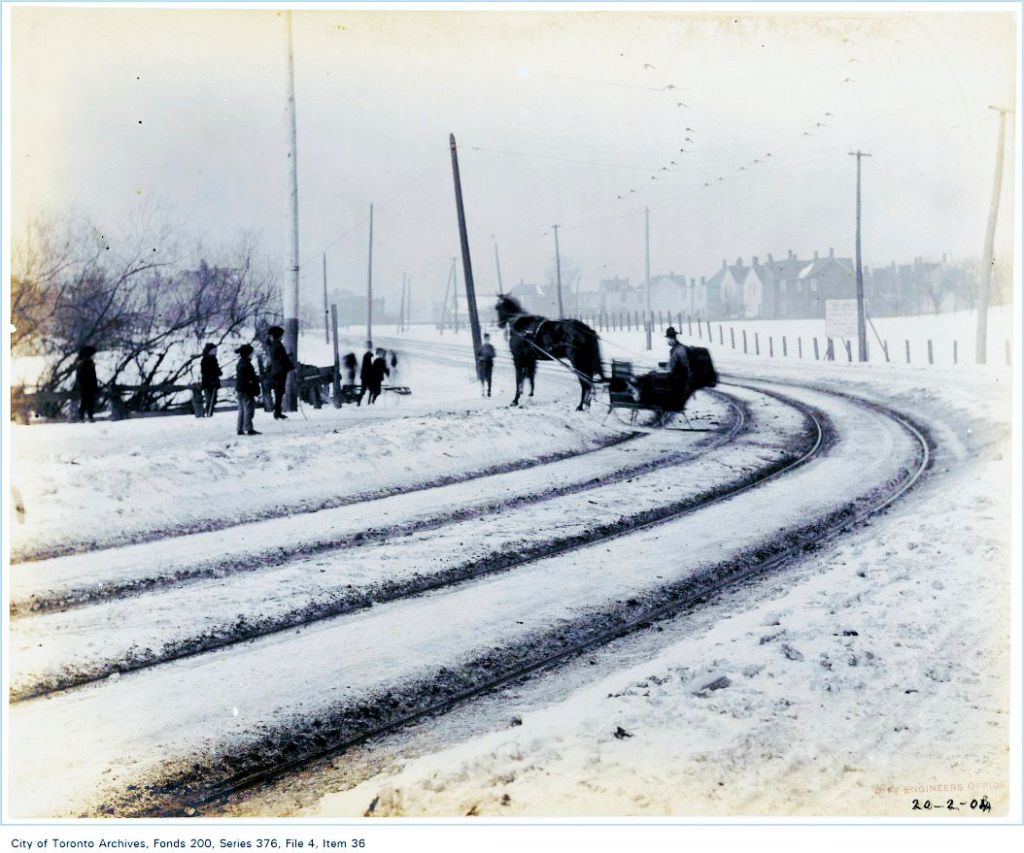

Thursday, Dec. 1, 1859 was a dark, moonless night. John Sheridan Hogan left Sarah’s home on Bay Street walked east across the Queen Street Bridge towards Alma Cottage across the narrow Queen Street bridge. It was dimly lit by gas streetlights. There were narrow pedestrian passageways on both sides of the 30-metre-long wooden bridge’s central carriageway, making it an easy trap. But John had gone this way many times before without a problem and he was a big, tall confident man. As he crossed the bridge, members of the “Brooks’ Bush Gang” asked him to, if they used the traditional words, “Stand and deliver”. Hogan flashed an unusual large roll of money but only offered to pay the usual “toll”.

Around 10:20 P.M., witnesses in nearby homes heard the sounds of a fight. A man shouted: “Mug him, throw him over the bridge, damn him!” Then something or someone splashed loudly into the Don River eight metres below. There was a gale of laughter, then silence. When Hogan recognized one of the gang, they beat him to death with a stone in a handkerchief and threw his body into the Don. He was only 44 years old.

No one missed Hogan for two months as they thought he was on a business trip. The first place authorities looked for him was in the United States. On March 30, 1861 John Bright and his three nephews were hunting for ducks in a skiff in the delta of the Don where it meets Ashbridges Bay. There they found a decomposing body floating face down in shallow water in the Don. The branches of a tree had snagged the corpse’s head and it had frozen in the sand, just bare skull with no face. A nearby fisherman told the duck hunters, “If that is Hogan’s body, you have got a prize.” The Government offered a $500 reward for information about the whereabouts of Hogan.

It was up to Toronto’s chief constable, 33-year-old William Stratton Prince, only in his job for ten months to find the murderers. Prince had Sarah Lawrie, James Beachell, and George Allen brought immediately to the Dead House (morgue) to identify the body. Sarah knew the flannel shirt and the collar that she’d sewed on the first night John stayed with her the week he disappeared. She recognized his underwear and the safety pin she’d used to repair it on the night he vanished. All three identified the corpse’s webbed toes. Later, Hogan’s tailor identified the coat and his boot maker recognized his enameled sealskin boots with the bulge made by Hogan’s bunion.

The coroner’s autopsy revealed no signs of violence, but the fashionable dark vest with red flecks that Sarah said Hogan had been wearing was missing, and the remaining clothes were torn in such a way as to point to violence. The coat pockets had been ripped off, and there was no money in the trouser pockets even though, according to Sarah, Hogan had been carrying forty pounds.

Prince suspected the killers were the Brook’s Bush Gang, infamous for collecting “tolls” from pedestrians crossing the bridge at night. The Brook’s Bush Gang has about forty members, both men and women, mostly Irish. The name came from a 40-acre woodlot on the east side of the Don River, not far from the New Gaol [the Don Jail][1]. This was a woodlot owned by Daniel Brooke’s Jr. and today’s Withrow Park. There the gang hid in a ramshackle barn, and lived on their takings from robberies, including lots of chickens from neighbouring farms, and prostitution. Some were hardened criminals, but most were ne’er do wells and hookers who came back to Brook’s Bush each night to sleep.[2] Brook’s Bush was outside of Toronto and the Toronto police left them alone. 23-year-old Jane Ward lead the gang, was the daughter of working-class parents. The Leader described Ward’s most remarkable feature as her “keen and scrutinizing eyes, with a peculiar glitter denoting a vicious and revengeful nature.”

Other gang members involved in murdering John Hogan were John Sherrick, James Browne [also spelled Brown], and Ellen McGillick.

“English John” Sherrick was 34 when Hogan was murdered. He had once been Beachell’s coachman and groundsman. Beachell fired him in 1857 because of his association with the gang. A handsome guy, he was Jane Ward’s and then Ellen Gillick’s lover. What a love triangle!

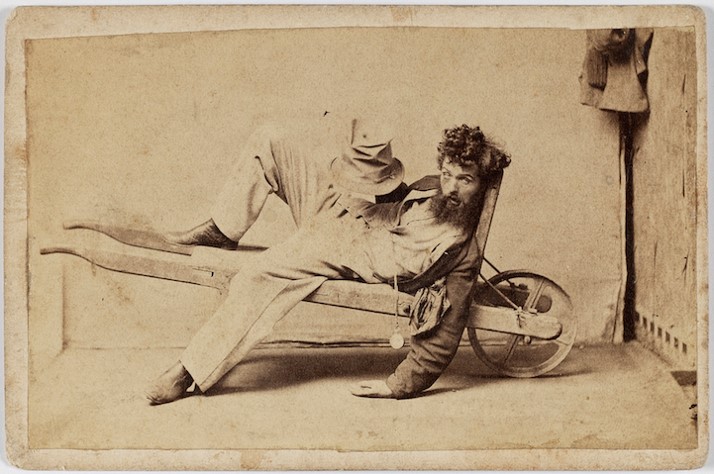

“English Jim” James Browne was 29, from Cambridge, England. He was, according to the Globe, “strongly built, but below the middle height, and has a repulsive countenance. His face is not improved by a cancer on his nose.” Browne joined the gang after being unable to find further work in boatyards and construction following an accident in 1857. He stayed with the gang even after other gang members stole and sold some of his clothes. A rather pathetic figure, picked on by the other misfits, Browne was likely dying from the cancer that was inexorably eating away his nose.

Ellen McGillick testified against Browne. Later she was arrested for an unrelated crime in Montreal and claimed she lied, and Browne was innocent. Later, on her death bed, Jane Ward herself admitted that Browne was innocent.

While the Globe estimated McGillick was “thirty,” the Leader thought she was about 23. It wrote: “She is a finely developed, well-built girl with a carriage of some grace.” Smallpox scars marred her otherwise pretty face. The gang was wary of her because she often informed on them to the police. She had a reputation as a truthful snitch. When cross-examined, she would say, “Your Worship, have I not always told the truth, bad as I am?”[3] Ellen McGillick turned to prostitution in her twenties when her husband deserted her.

Hogan and the gang were casually acquainted. On visits to the jail to gather material for newspaper stories, he gave a few coins to jailed members. He often passed other gang members on the bridge as he walked to Beachell’s and they headed for Toronto’s saloons and whorehouses. When Sarah warned John Hogan the night of December 1, 1859, to “watch out for the Brook’s Bush Gang,” he dismissed her. “They’ve never molested me, although once or twice some of them have stopped me and I’ve had some difficulty getting past them. But they know me well. I’m sure they won’t hurt me.”

Two days after Hogan’s body was found, Detective James Colgan reminded Ellen McGillick [Ellen liked Colgan – they were both from County Meath] of the favour he had done her by not sending her to prison after she’d almost killed him with a knife. Ellen just couldn’t keep her mouth shut. She was a “blab”. She dropped hints for months that she had “something to tell about Hogan’s disappearance.” So, she poured it out when Det. Colgan gave her the chance. Jane Ward had pounded Hogan with a “tag”–a stone wrapped in a handkerchief. She then with Sherrick, Browne, and Hugh McEntameny (another gang member since deceased) threw the body off the bridge while Ellen McGillick watched.

McGillick showed the police where they had cut off a piece of the handrail because Hogan’s blood was splashed over it. Colgan cut off a nearby piece for analysis. They found traces of blood, but with the technology and science of the day, were unable to say whether the blood was human. The police found Hogan’s vest in the possession of the owner of a tavern where the gang hung out. An elderly doctor, Thomas Gamble, gave a statement to the police, saying he had heard something that December night, but thought that, because he not very close, “mug him, throw him over” was referring to a dog. He was an old man and feared going out to confront whomever was making mayhem on the bridge.

Jane Ward and Browne were captured quickly. The search for Sherrick ended April 12 when he was found in the Kingston Penitentiary for another robbery. The trial was set for April 29, one month less a day after Hogan’s body was discovered.

Several high society ladies, who had persuaded the guards to let them in the courtroom early, took the best seats. When Ward, Sherrick, and Browne came in, the spectators leapt to their feet for a better view. Some stood on chairs, others climbed into the jury box or onto the judge’s bench. The trial was a sensation.

The lead prosecutor was Henry Eccles. The head defence lawyer was James Doyle. It was Doyle’s first murder case. The judge was Chief Justice Sir John Beverley Robinson, a leading member of the Family Compact. He granted Doyle’s request that Browne be tried separately because not all his witnesses were present.

Sherrick’s alibi was that he had been chopping wood north of Toronto when Hogan was killed. But the man who claimed to have witnessed this had made a diary entry that was in the middle of a page dated November and in different ink. “I might have put in fresh ink when I made the middle entry,” the man said. “And took it out when you made the bottom entry,” was Eccles’s devastating reply.

The trial lasted only two days. It all depended on loud-mouthed, bad, but “honest” Ellen McGillick. Did they believe her? They didn’t. “Both not guilty,” the foreman said at 10:00 P.M. Sherrick was returned to Kingston Penitentiary to continue his other sentence. Robinson cautioned Jane Ward: “I would say to you that the sooner you abandon the disreputable life you have been leading, the better.” Prostitutes had a short life expectancy not only because of the drinking and violence associated with the world’s oldest profession, but because syphilis was rampant in the Victorian era and there was, before antibiotics, no effective treatment.

Browne’s trial, watched by fewer spectators, was on October 8. Doyle represented him, too. York County Crown attorney Richard Dempsey, Hogan’s friend, acted for the prosecution. Sherrick and Ward were called as defence witnesses. “I did not see Browne in early December 1859 because I was not here,” Sherrick said. “I never saw Browne, Sherrick, McGillick and McEntameny all on the bridge at one time,” Jane Ward said. Save for Sherrick’s witnesses, the testimony was identical to the Ward-Sherrick trial. Yet this jury believed Ellen McGillick. It doesn’t pay to have a “repulsive countenance” with “a face … not improved by a cancer on his nose.” The jury found Browne guilty. “I am innocent. I never even heard of the murder until I was arrested,” Browne insisted. He was scheduled for execution on December 4, but Doyle persuaded the appeals court to grant a retrial. It was on January 10, 1862. Again, Browne was found guilty and again he protested his innocence.

Two weeks before the scheduled execution, Doyle submitted a petition pleading for commutation to life imprisonment to the governor general, Viscount Monck. It was signed by many sympathetic Torontonians who felt Browne, like Ward and Sherrick, should be given the benefit of the doubt. The petition was ignored.

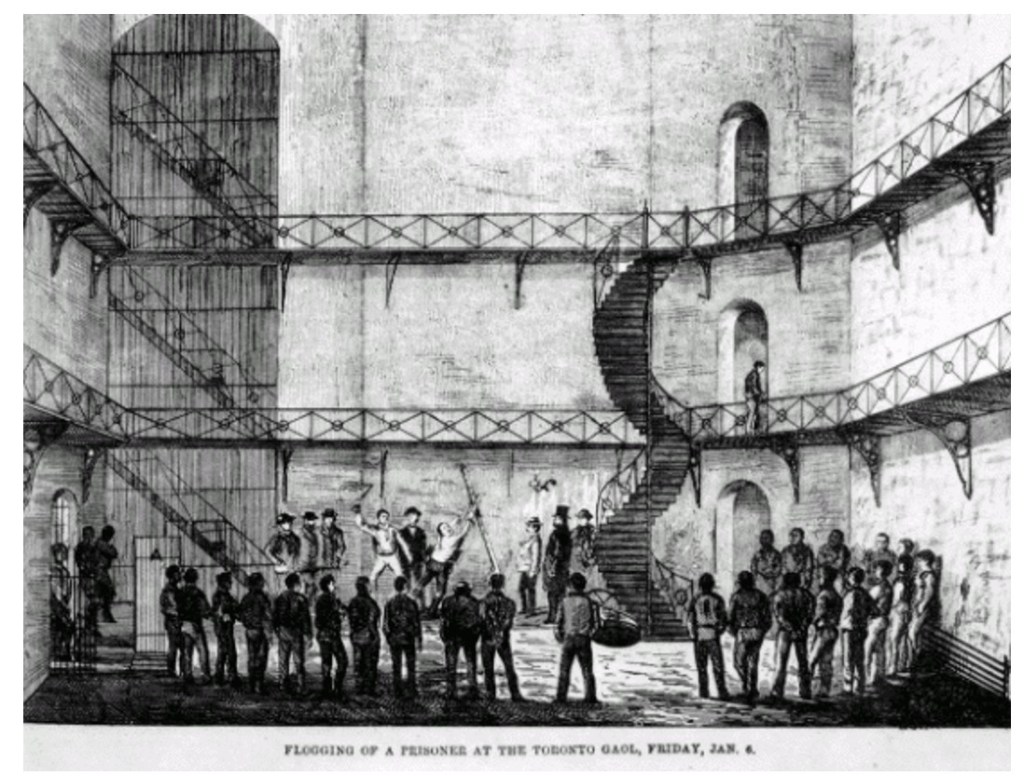

With executions regarded as entertainment by many, a large crowd of 5,000 gathered within the city jail walls and on the grass outside to watch. Cab, wagon, and cart owners charged a shilling per person for shoulder-to-shoulder standing room on their vehicles. On the scaffold Browne murmured, “I say with my last breath, I am innocent.”

Browne’s execution on 10 March 1862 was Toronto’s last public hanging. His last words were:

My friends, I want to say a few words to you. I have been a very bad man, and now I am going to die. I hope it will do you good, I hope this will be a lesson to you, and to all people, young and old, rich and poor, not to do those things that has brought me to my last end. Though I am innocent of the murder, I am going to suffer for it. Before two minutes are gone I shall be before my God, and I say with my last breath, I am innocent of the murder. I never committed a murder in my life, and I shall be before my God in a few minutes, And may the Lord have mercy on my soul. Amen.[4]

Hogan was interred in a plot purchased by Beachell in Toronto’s St. James Cemetery. Beachell and other friends subscribed for a monument in Hogan’s memory, but it is no longer there. It was worn away by harsh weather, as gravestones of that era often were. Browne was buried in an unmarked grave in the nearby Necropolis. The bridge from which Hogan was thrown was swept away in 1878 by a rainstorm. [5] During the trial of the Brook’s Bush gang, local residents such as Cubitt Sparkhall, went into the woodlot with axes and chopped down every tree and leveled the old barn to the ground. One by one, the members of the Gang succumbed to alcoholism, suicide, death by hypothermia, syphilis, dying young and unlamented. That was the end of the Gang, but not the end of the story.

Some believed Jane Lewis was actually Jane Ward despite the record death of Ward.

Jane Lewis was possibly the most notorious poorhouse resident. A member of the Brooks Bush Gang, which terrorized Toronto residents in the 1860s, she fled to Guelph after a fellow gang member was hanged for the murder of a politician named John Hogan. She arrived at the poorhouse in declining health in the late 1870s, but lived there for 30 more years until her death at the age of 101. The cause of death was “senile decay.” In addition to her reputation as a heavy drinker and a pipe smoker, Lewis was remembered for the motherly care she gave to a little orphan boy at the poorhouse. His name? Wellington Robertson.[6]

And the sites that Jane Ward and her band of tramps and thieves frequented can still be visited:

Historian John P. Wilson, noted:

While others have told the story of the Brook’s Bush Gang in compelling ways, this telling is distinctive in placing the story in locations that can be visited, experienced and treated to the subject’s unique imagination.

Danforth Avenue at Hampton, by St. Barnabas Anglican Church – At daybreak Brook’s Bush denizens, returning from several weeks’ labour in the fields and pantries of Durham County, roll off a farmer’s wagon as the farmer pushes on towards St. Lawrence Market to set up a stall for selling produce and country wares.

Withrow Park, deep in the forest on the hill above today’s skating rink – Brook’s Bush Gang quarrel over the day’s haul. There is an uneasy power balance between the men, who bring in small amounts (from picking pockets and performing day labour in town) or large amounts (from weeks of farm labour or one quick B&E at a York East farmhouse), and the women, who bring in small amounts (from household chores and market hustling ) or large amounts (from anticipating and complying with the peculiar, private desires of the lettered and propertied gentlemen of the town).

Butcher’s Arms Tavern, Mill Road (Broadview Avenue north of Millbrook, the Broadview Arms apartments now stand here) – Brook’s Bush Gang members spend ill-gotten gains on the cheapest whiskey and watered-down beer in a smoky, putrid saloon, plotting together another scam, cheat, snitch, cover or play to get rich and escape the cold, rough nights in the Bush.

The Soggy Bottom, Ingham Avenue, between Millbrook Crescent and Bain Avenue – Brook’s Bush Gang revel the late hours of the summer night away, asserting their wills over rivals, gambling, drinking, flirting and fighting at story-slams, cock-fights, cur-baits, prize-fights and slap-downs.

Withrow Park, in lean-tos and caves below the hillock – Brook’s Bush Gang crashes into stupefied oblivion, battered and slashed from hot-headed fighting, or nestled in the arms of this season’s lover.

Don River Bank below Gerrard Street (Bell’s) Bridge – Brook’s Bush Gang skulk down the weedy riverbank at dusk, avoiding the toll-keeper’s cottage at Mill and Kingston Road (Broadview and Queen). They aim to set up hustles and ambushes on the Kingston Road (Queen Street) bridge for those farmers and townsmen who look for distractions late at night where upstanding yeomen and gentlemen ought not to be.

King Street in Corktown, near Little Trinity Church – Jane Ward stakes out a dark sidewalk corner and waits for a gentleman who shows promise of being an easy mark. The other gang members hide near the bridge over the Don River. John P Wilson, Oct. 2011

1818 ca. Regarding Daniel Brooks Sr. “That our old defenders were jealous of the honor and integrity of the regiment to which they belonged, the following curious petition to Sir Peregrine Maitland, then Lieutenant- Governor of Upper Canada, testifies. It is copied from the original draft on the water-lined paper of the date:

‘To His Excellency Sir Peregrine Maitland, K.C.B., Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada and Major-General commanding His Majesty’s forces therein, etc., etc., etc.

We, the Undersigned Non-Commissioned Officers and Privates of the … Company of the 2nd Regiment of York Militia, beg leave to approach Your Excellency with the purest sentiments of Loyalty and Attachment to His Majesty’s Person and Government, who has given us an additional proof of his paternal care for this distant part of his extended Dominions in placing over us as his Representative an Officer of Your Excellency’s distinguished Rank and Character.

Feeling as we do, that nothing can be nearer Your Excellency’s Heart than the preservation of that Honor and integrity in all ranks of the Officers of the Militia of this Province, which as a Military Character You must always have revered, we come before your Excellency with the more confidence to state what we humbly conceive to be derogatory to the Honor of the Corps to which we belong.

Captain Daniel Brooke, who has been appointed to the command of the ___ Company, has been publicly accused by his Brother-in-law with Felony and other heinous offences, which accusations have never to our knowledge been satisfactorily answered, in Consequence of which, without any evil Intention of opposing the Laws of the Country, we unthinkingly determined not to serve under a person of his Character.

We are now, however, fully convinced of the tendency our conduct had to Insubordination, and are sorry we should have been guilty of such Misconduct, and will in future faithfully discharge our duty under the orders of any person Your Excellency may appoint over us. Nevertheless, we shall feel much gratified should Your Excellency be pleased to grant us the Indulgence of placing another Officer in the room of Captain Brooke, whom we can never respect as a Man, however we may be inclined to obey his orders [as] a Captain in the Militia of Upper Canada.

We are, with the highest sentiments of Esteem, Your Excellency’s most obdt. and very humble servants:

Richard Thomson, Adna Bates, jun., Gideon Cornell, Earl Bates, George Cornell, Andrew Thomson, Thos. Sweeting, Wm. Jones, David Thomson, Archibald Thomson, Peter Little, Christopher Thomson, James Thomson, John Martin, James Taylor, Andrew Johnston, Joseph Secord, William Thomson, Levi Annis, John Miller, Thomas Adams, Wm. Robinson, John Crosby, James Daniels, William Thomson, John Thomson, James Thomson, Peter Secor, Amariah Rockwell, Isaac Secor, Peter Stoner, Jonathan Gates, John Laing, Stephen Pherrill, John Stoner, Abraham Stoner, Adna Bates. Scarboro.’

He owned the bush in York township which, in after years, formed a rendezvous for the notorious “Brooke’s Bush Gang.” This Brooke had no connection with a family of the same name in the township, one of whom was a well-known old stage-driver.

The document is not dated, and there is no record among the papers as to whether this unique petition was granted. It probably was, and a better man than the objectionable captain appointed. The petition of which this is a copy is in the possession of Mrs. W. Carmichael, who kindly permitted us to use it here. Mrs. Carmichael is a granddaughter of the pioneers David and Agnes Thomson.”

[Ed.: Sir Peregrine Maitland was Lt.-Gov. of Upper Canada from 1818-1828. David Boyle, the author, was the organizer of the Canadian Institute, the “Father of Canadian Archeology”, and the excavator, along with William Henry Vander Smissen, of the aboriginal Withrow Site in 1886.][7]

Hopkins, North Toronto Post, loc. cit. (1792-1872 or 1873) married Charlotte Player, daughter of John Playter, Jan. 2, 1820. He was a man of considerable property and one of that city’s [Toronto’s] prominent citizens.” (Province of Ontario)

1833 The Daniel Brooke building is at 150-154 King Street East, at on the northeast corner of King and Jarvis Street. A 1994 Toronto Historical Board plaque states:

This building was first constructed in 1833 for owner Daniel Brooke, a prominent merchant in the Town of York. It was substantially rebuilt between 1848-1849 prior to the Great Fire of April 1849 which started in a nearby stable. While much of the business district was destroyed, this building escaped major damage. It housed a variety of commercial enterprises over the years, including the prosperous wholesale grocery business of James Austin and Patrick Foy in the 1840s. Austin went on to become a president of the Consumers’ Gas Company and of the Dominion Bank. His home, Spadina, became a museum in 1984. During the mid-19th century, the Daniel Brooke building contained the offices of The Patriot, an influential conservative newspaper. The block is a rare example of Georgian architecture in Toronto.

1855 Seven women and four men were charged with leading disorderly, good-for-nothing lives. Sergeant McCaffrey had received information that a gang was living in Brook’s Bush. He went there and discovered the prisoners carousing over a log fire, in a hut erected after the Indian fashion. The dwelling these unfortunates is described as consisting of several layers of large pine boughs, rudely thrown together and a cavity preserved in the centre by upright poles and cross pieces. The only things in it were a big cast iron pot, some bread, herrings and a jug of whiskey. The women were pretty beat up, with scratched faces and black eyes. The youngest were about twelve or thirteen and the oldest about 20. The men were fined and the women sent to jail for a month. Globe, January 16, 1855

Robert Wagstaff, Thomas Thorn, Lawrence Cassidy, William Reid, Jane Russell, Sarah McClusky, Sarah Fielder, Sophia Barber and Jane Greenfield were charged with “leading a disorderly life”. The men were healthy and could work. The women were a set of filthy looking creatures, clad in rags, and the majority of them not more than seventeen years of age. On Saturday forenoon the Police Magistrate received information that a number of disorderly men and women had erected a wigwam in the bush near the Don and were inhabiting it. They subsisted by robbing the surrounding farmers of fowl, fences, and potatoes, etc. Sgt, McCaffrey led a posse and raided the wigwam, burning it down. The men were fined and the women sent to jail for a month. “The unfortunate creatures laughed heartily at the idea of their confinement being considered a punishment.” Globe, March 14, 1855

Jane Ward—accused of disorderly conduct by district constable Joseph Beck, was sent to jail for a month. Globe, July 10, 1855

1856 On July 21, the Brooks Bush Gang murdered Isaiah Sewell, a Black teenager from Leslieville. He was going from his family’s home at Logan Avenue and Queen Street to buy hay from a farmer on Broadview Avenue to provision the Sewell herd of horses for the winter. He had ten pounds on him worth about $2,500 Canadian dollars today. This was a lot of money.

Young Sewell met up with some of the women of the gang, sex trade workers, including Catherine “Kate” Cogan [also spelled Colgan], and Michael Barry, about 40 yards northwest of the railway track (at what is now Logan and Carlaw). Barry was new to the Gang, having arrived in Toronto only a month before and was only a casual visitor to the Bush.

Andrew Jenkins a pimp, signalled the women to go meet the teenager. Jenkins remembered someone saying, “it was a shame for a white woman to be seen with a black man.”

Sewell didn’t follow the most direct route to Bergin, the man with the hay. Isaiah may have been following the course of Holly Creek which ran through Withrow Park, the site Brooks Bush. Another possibility is that Sewell walked along the railway tracks. Jenkins, saw Sewell drinking with the women. Jane Ward, the leader of the gang, Katherine O’Brien, Samuel Joslin, and John Clyde joined the group around Sewell. Cogan later claimed that Michael Barry came through the undergrowth and struck Sewell from behind with a bottle, calling Sewell “a black bugger”.

Cogan claimed she picked a package of folded up newspaper from the ground when Sewell fell and there was money in it, but she didn’t know how much. Jane Ward forced Kate Cogan to give up a sum of money which she had concealed in her bosom. Ward then turned it over to a market gardener named William Rhodes to give to the authorities.

The Court was occupied for several hours in investigating the circumstances attending the death of Isaiah Sewell, a colored lad, who was murdered on Monday evening last, in Brook’s Bush.

JOHN CLYDE, PATRICK MATHEWS, SAMUEL JOSELYN, ANDREW JENKINS, WILLIAM KERR, JANE WARD, CATHERINE O’BRIEN, CATHERINE COGAN, and JANE GRANTFIELD arrested upon suspicion of being concerned in the foul deed were placed at the bar. The evidence, which was gone into at great length, adduced that the deceased boy had been sent by his father to the city, to pay an account of $30 or $40. On his way, he unfortunately fell into the company of a number of loose characters, who frequent that locality, and was induced to remain with them. A manned named Michael Barry, jealous of the attentions he bestowed upon one of the women, struck the deceased on the head with a large bottle, killing him instantly. Information was given to the father of the poor boy, who lost no rime in getting the assistance of Sergeant McCaffry and a posse of police from the City Hall Station, and the above arrests were made. After going into the facts of the case at great length, Patrick Mathews, Jane Grantfield, and Samuel Joselyn were discharged, and their evidence taken. Barry, the principal in the fatal occurrence, has not yet been made amenable. The other prisoners were remanded for further examination.

The Court then adjourned at half-past five o’clock. Globe, July 24, 1856

Michael Barry had gone into hiding but was spotted in Port Hope by a former Toronto police officer and arrested. County Constable Higgins went by train with Jane Ward to arrest Barry. He needed Ward to positively identify the prisoner. Globe, July 29, 1856 Michael Barry went to court to face the charge of “Wilful Murder”. He did not seem to understand the danger he was in and, when the judge asked him if he had anything to say, Barry shrugged and said, “I guess not.” Globe, Aug. 1, 1856

The Brooks Bush Gang gained publicity due to the murder of Isaiah Sewell, William Davis, councillor, owned property in the Bush and annoyed by their robbery pressed charges and ten of the gang, five women and five men, were arrested: “the lowest of the low”. None of the defendants could raise bail so all went to prison. Globe, August 23, 1856 Not long after, Jane Ward was sentenced to a month in prison for being drunk and disorderly. Globe, Sep. 9, 1856

In October, Michael Barry went to trial for the murder of Isaiah Sewell. William Kerr, a railway worker, like Michael Barry, testified at the trial. Kerr had been the one who informed Samuel Sewell of his son’s death. Kerr testified that Barry struck Sewell from behind, shouting “You black — —- get up and go away!’

Mary Sullivan who knew Isaiah Sewell also testified. She noted that Sewell had been injured in a fall from a wagon, sustained a head injury and was subject to spells of dizziness (possibly epilepsy). Dr. William Russell, the coroner, had autopsied Sewell’s body. The cause of death was a blow to the head. After 45 minutes deliberation, the jury delivered a verdict of manslaughter. Witnesses stated that Barry had not struck Sewell hard and expected him to get up, but the teenager died. Globe, October 30, 1856

Jane Ward, again convicted of being drunk in public, was fined and sent to jail for a month. Globe, Nov. 10, 1856 A month later, Jane Ward was sent to jail with hard labour for a month for being drunk and disorderly. Globe, Dec. 10, 1856

1857 Cubitt Sparkhall, who owned land near the Bush, laid charges against the Gang and Sergeant Smith and a posse went and arrest eleven of them: William Tronting, John O’Beirne, Robert Brown, James Brown, James Harraghy (Hagerty), Rose McCaffrey, Catherine Cogan, Jane Grantfield (Greenfield), Jane Ward, Sarah Fielden, Louisa Woods and Susan McCormack. Many of these had been arrested for aiding and abetting in the killing of Isaiah Sewell, but only Michael Barry was convicted. Sparkhall testified that the Gang had their headquarters on a public Road (Logan Avenue) near his land and were “continually plundering my land of rails and lumbers for firewood. They have taken up their abodes in bush shanties, which they form from the woods.” They also stole chickens from him and his neighbours. Globe, April 8, 1857

Jane Ward was again sent to jail for one month at hard labour for being drunk and disorderly. Globe, May 16, 1857 That summer James Grantfield, Jane Ward, Jane Brown, Joseph Wright and James Gurley, members of the Brook’s Bush Gang, were in court for breaking the peace. They hadn’t been able to come up with bail while they waited for their trial. The magistrate let them off with a warning. Globe, July 11, 1857 But the next lot weren’t so lucky. Police charged James Gokey (aka DeLavelle), Thomas Redmond, Andrew Jenkins, Samuel Hannon, Susan McCormack, and Mary A. Walton, all members of a gang that lived in Brook’s Bush and developed a modus operandi of waylaying and robbing travellers going over the Don Bridge. The bridge itself was constructed with high walls making it an ideal trap for the unwary pedestrian. The gang could let a potential victim in at one end of the bridge then close off escape by standing there while others blocked the other end of the bridge. A citizen remarked, The eastern end of the city is not safe from the number of low characters who infest the Bush. Globe, August 11, 1857 Six women and five men, all Brook’s Bush Gang members, were convicted of disorderly conduct and sentence to a month at hard labour in jail.

That fall Jane Ward went to jail for a month at hard labour for being disorderly. Globe, November 14, 1857. But worse things were to come. ON Christmas Eve an inquest was held on the body of a baby found in Brook’s Bush. Both the new born and mother, Bridget McGuire, had suffered from exposure in the harsh weather. The baby was born alive but died of hypothermia. The mother was treated in hospital. The unfortunate mother was laying on a little hay saturated with snow and rain, with her dead infant reclining on her arm, with no covering of any description. Globe, December 25, 1857

1858 Brook’s Bush member Samuel Hannah was convicted of passing counterfeit money. Globe, January 1, 1858

A Parcel of Thieves

Matthew Flynn, a rough looking fellow, and Catherine O’Brien, Catherine Hogan, and Bridget Maguire, three denizens of Brook’s Bush, were placed at the bar charged with several acts of robbery.

From Sergeant Smith’s evidence it appeared that a number of robberies have been lately committed in the eastern part of the city. Hen-houses have been robbed, clothes lines stripped of articles of apparel, and several other sets of theft have taken place, rendering it unsafe to leave in yards or gardens any articles capable of being easily taken away. In order to detect the marauders Smith and Corbet were appointed for special duty. About 1 o’clock this morning they observed two men on Parliament Street, and called upon them to stop. The men, however, took to their heels; but the officers pursued them and succeeded in capturing Flynn, who had concealed himself in a culvert at the corner of Don and Parliament streets. A large quantity of pillage, the fruits of his night’s adventures, was found in the culvert near him. The property consisted of shirts, caps, a pail, an axe, an iron pot, and a variety of other things which they had evidently left in the culvert at different times. The prisoner was secured, and it was surmised by the sergeant, from the direction the fellow was going in, that Brooks Bush was his destination. The officers accordingly went there, and found three pair of poultry, two geese, three lanterns, two boilers, and other property. They likewise saw there the three female prisoners who were at that late hour preparing supper for expected guests. Flynn and his runaway comrade being presumed to form two of the invited parties. The officers took charge of the plunder and brought all the prisoners to the station.

Flynn, who acted with great effrontery in court, and appeared as if he had recently been drunk, said the few things found with him were his own. “The fact was,” said the prisoner, “I owed a little rent and not wishing my traps to fall into the hands of my landlord I took this means for their preservation.” He lamented he had not a good lawyer who would “clear” him. To refute this story Mr. Franci Langril, St. Lawrence Market, and a Mrs. Hagarty, and a Mrs. Murphy identified all the articles found with Flynn as their property and deposed that the goods had been stolen from their respective premises during the night.

Mr. Gurnett sent the male prisoner for trial upon three charges, and remanded the females until tomorrow. January 28, 1858 Matthew Flynn was convicted and sentenced to two years in the penitentiary.

A Letter to the Editor called for Brook’s Bush to be cleared of the Gang and the members forced to do hard labour. Globe, January 30, 1858. A week later Sgt. Smith arrested Patrick Matthews, Samel Jocelyn, Catherine O’Brien, Catherine Cogan, and Margaret Maguire, members of the Brooks Bush Gang, on charges of robbery committed on January 26. Globe, February 6, 1858

William Brown, Robert Brown, John Pigeon, Patrick Matthews, James Harraghy (Hagerty) and Samuel Josleyn were tried for stealing from Richard Boles. The other charges against them were dropped. Boles went to the Bush and found his missing property in their shanty. Robert Brown, John Pigeon and James Harraghy were convicted. Globe, April 7, 1858 Two days later James Harraghy, William Brown, P. Matthews, Samuel Joselyn, Robert Brown, and Bridget McGuire were all charged with theft and being receivers of stolen property. The jury acquitted William Brown and convicted the rest. Robert Brown, having been convicted of larceny the week before, went to the city jail for ten days, and at the end of that term was to spent three years and two months in the penitentiary. P. Matthews was sentenced to three years and two months as well. Samuel Joselyn was sentenced to three years and four months. Bridge McGuire got two years and one months. John Pigeon, another member of the Gang, was charged in a separate indictment, convicted and sentenced to ten days in the city jail, followed by five years in the penitentiary. Why so long? He had a previous conviction for theft in 1852. Globe, April 9, 1858

Mary Ann Walton gave birth to a baby in Brook’s Bush…from the fact that the infant has not been seen for some time, it is suspected that it has been foully dealt with. Globe, June 14, 1858

The Gang attacked two passerbys, one of whom escaped. The other was hit on the face, neck, and shoulders with a black bottle, the same kind of weapon used to kill Isaiah Sewell, and like Sewell was badly cut up, but this victim survived to identify his assailants. Globe, June 22, 1858

That fall Sgt. Smith again arrested a number of the Gang, including William Haslem, Thomas Wells, William Carr (Kerr), Thomas O’Bryan, James Brown, Sarah Fielder (Fielden), Jane Ward and Mary Ann Walton. The Gang had been holding up travellers on the Kingston Road and in the neighbourhood. The men were fined, but the women went to an “already overcrowded” jail. Globe, September 3, 1858 Cornelius Leary, a Gang member, was convicted of assaulting Mary Sheppard, another member of the Gang. He couldn’t pay the fine and court costs, so “was sent to break stones for a month.” Globe, September 7, 1858

Jane McDonald, Margaret Evans, Sarah Fielder, Mary Ann Walton, Mary Crooks, James Brown, and Thomas Wills, all Brooks Bush Gang members, were convicted of being disorderly. As usual, the men were fined, and the women went behind bars for a month. Mary Cary, another gang member, was also arrested and sent to jail for a month. Globe, Nov. 16, 1858

Jane Ward, Margaret Hagerty, Annie Lee, and Bridget Greenan, all of them witnesses at the inquest on the body of Thomas Madigan alias Reardon were sent to prison for one month each as disorderly characters. Globe, Dec. 10, 1858. Madigan had been stabbed to death with a bowie knife outside a notorious tavern on Wellington Street where Patrick Welsh was the landlord. (Reardon was his alias because though born Madigan, he was adopted by a Daniel Reardon when young. Daniel Reardon Jr. was with Madigan the night of the murder.) Madigan had lived a quiet respectable life until he fell into bad company. He had quit a good job with a Toronto merchant the week before.

William (also known as James) Fleming, a telegraph operator with the Grand Trunk Railway, was charged with the murder of the twenty-year-old. Fleming worked at Union Station but had been laid off several weeks before the murder. Police arrested seven “bad characters” hanging about the Welsh’s bar – members of the Bush Brook Gang, including Annie Lee who was working as a prostitute and was paid a half a dollar for some service she offered but then refused to perform. Fleming then assaulted her. He was chasing her when Madigan pushed him off the sidewalk. Drunk and enraged, Fleming stabbed Madigan. Later Fleming asked the bartender at the Young Canadian Saloon where he lived, to hide the knife.

Welsh’s Commercial Saloon was “a rendezvous for the lowest class of prostitutes.” Another Brooks Busher, Patrick “Patsy” Scott, a shoemaker, was also there. Annie Lee and Bridget Greenan both sported black eyes. A reporter described the females: “The women are of the very lowest class; several of them are dressed in tawdry clothes, whilst the others have scarcely a rag on their backs.” Globe, December 7, 1858, Fleming was convicted in the murder and sentenced to death. He was hung on March 4, 1859. He confessed to the murder just before his death.

1859 A retired soldier of the 71st Regiment, James Innes, was drunk when he was solicited by a hooker on Wellington Street. He bought another court of whiskey and accompanied her to Brook’s Bush. Next morning he woke up, cold, lying on the Grand Trunk Railway Tracks near the Don bridge. No wonder he was cold—he found himself in only his underwear and a shirt. Not only were his clothes missing, but also his money. The half-naked man went downtown and reported to the Detective Greaves. The police quickly recovered the missing articles and arrested “Yankee Mary” at Brook’s Bush. Robert Wagstaff was with her and police searched him too, recovering Innes’ empty wallet, his pocket knife and a Methodist hymnal. Globe, April 1, 1859

Wm. Reid and Henry Miller, one of whom belongs to the notorious Brook’s Bush Gang [William Reid], were then brought up on a charge of stopping a young man on the Don Bridge on the evening of Saturday. This person gave information to the police, and Sergeant Hastings went to the place and apprehended both prisoners. The prisoners offered to leave the city forthwith, and they were discharged. The Magistrate appeared to be strongly inclined to send both of them to prison for a month as disorderly characters but relented after hearing their strong protestations of future good behaviour. Globe, May 10, 1859

Jane Ward and Eliza Sanderson were both found drunk on the streets, and sent down to their old quarters, the gaol, for a month. Globe, May 16, 1859 A little more than a week later Maurice Malone, John Clyde, John, Esson, Margaret Hagarty, Elizabeth Nolan, Mary Ann Pickley, Mary Ann Flanaghan, and Bridget Drew, all belonging to Brook’s Bush, were arrested and jailed on charges of being disorderly. Globe, May 24, 1859

Jane Ward and a man named Busby, two well-known bad characters, were apprehended yesterday forenoon, on the charge of being connected with the robbery of the man named Donaldson, in the College Avenue on Sunday evening. Ward is the girl with whom Carr (Kerr)…cohabits. Donaldson, in his evidence, states that he was at the house occupied by her on Richmond Street on the night of Sunday; he denies that she was in the Avenue. She and Busby were found yesterday in a tavern near the Don, where they had been all night. No money was found on either of them. Ward had bought a new cloak, and Busy states that she was spending money freely on Monday. Both of them deny all knowledge regarding the stolen watch. They will be brought before the police magistrate this morning. Globe, June 11, 1859

A Brook’s Bush Lot.

Maria Reid, Mary Sheppard, Catherine O’Brien, Harriet LeGrasse, Mary Martin, and Ellen McDonald, all of them “unfortunates,” and belonging to the celebrated Brook’s Bush gang, were placed at the bar, presenting a motley appearance, charged with conducting themselves in a disorderly manner in the bush in rear of Mr. Ridout’s residence, head of Sherbourne Street.

Sergeant Major Cummins stated that having received information of what was going on in the bush in rear of Mr. Ridout’s residence, he went to the place on Sunday afternoon, accompanied by a posse of constables. The moment the girls saw the police they scampered off, but the constables succeeded ion apprehending them all, and conveying them to the station, where they were locked up. The men belonging to the party had all decamped before the police reached the place. The prisoners had set fire to the underbrush, and it seemed, from the appearance of things, that they had been taking up their abode in the bush.

The prisoner Reid, who formerly moved in a respectable circle in Toronto, said that she, along with the other girls, went out for a walk. When they got to the bush they saw some boys catching bird, and they looked on to see the fun. They observed the constables coming, and, for her own part, as she would as see “Auld Clootie” [The Devil] coming as a constable, she ran off and the other girls followed. (Laughter.) The police, however, caught them all and took them into custody. She could assure the Magistrate she was only out for a walk for the good of her health. (Laughter.)

The Magistrate (to Sergeant Cummins) They are all notoriously bad characters, are they not?

Sergeant Cummins: They are, your Worship.

Prisoner Reid: How can we be notoriously bad characters when your Worship keeps us all the time in gaol, a place where we can’t get at any mischief. (Laughter.) I have been in a gaol ever so long. (Laughter.)

Magistrate: Well I suppose you are far better off down there than anywhere else, so I will send you all to gaol for another month, although I doubt much if it will have any good effect on you.

The prisoners left the court laughing and jeering. Globe, June 22, 1859

Jane Ward and John Busby were remanded for stealing a silver watch, gold seal and brass key from Thomas Donaldson. The judges commended Detectives Greaves and Westall for their work on the case. They had found the stolen property buried near the house where Ward and Busby had been living. Globe, June 24, 1859 Ward and Busby were sent for trial. Globe, June 29, 1859 While being taken to court, Jane Ward and William Carr (Kerr) escaped. (The charges against John Busby had been dropped.) Ward and Carr returned to court, this time in handcuffs. Globe, July 7, 1859 William McGee was found guilty of helping prisoners escape. Jane Ward, testified in his defence. Globe, July 12, 1859

Less than a week later, Robert and Charlotte McLaughin, their daughters Rose and Charlotte, Jane Ward, Alice Thompson, Mary Reardon and Patrick Scott were all charged. The McLaughlin family were running a brothel on Richmond Street where the rest of the Gang were caught as found-ins. The women were probably working there, and Scott a pimp. The McLaughlins had been living there for about a year and caused problems, making it hard to rent a house anywhere near theirs. They fought, cursed and swore, and there were shouts of murder. Mary Reardon was known to be very violent. The McLaughlin girls, both under 15 years old, worked as whores. At the time of the arrests, Rose McLaughlin was bleeding heavily from wounds inflicted in a fight. Scott was drunk and ran off, but was caught. All were convicted and sentenced to a month at hard labour, except Charlotte McLaughlin who recently had a baby. Gaol regulations did not allow babies to be let in. Globe, July 15, 1859

The Brook’s Bush Gang Again

A considerable number of this band of ruffians are again in custody, charged with viciously assaulting and robbing one Edward Closghey [McCloskey]. A warrant had been out against them for a couple of days before their capture, and on Saturday Detective Greaves having found out their lurking place, gave information to the Chief of Police. Their arrest was entrusted to a strong body of constables under the direction of Sergeant-Major Cummins and Sergeant Hastings, by whom they apprehended near the new gaol ground [the Don Jail]. One of the fellows—a man a named Tuck [James Tuck]—on seeing the police close upon them, took to his heels, but was hotly pursued, and run down and captured by Constable Paterson. Among the party is a desperado named [John] Clyde, who since the committal of Carr [William Carr or Kerr], the former ringleader, to the Penitentiary, has been the foremost of the gang. They will be arraigned at the bar of the police court this morning. Globe, August 15, 1859

John Clyde, James Tuck, Denis O’Dowd, Edward Short, Martin Kelly, William Macpherson, Mary Ann O’Bryan and Elizabeth Nolan were arrested for robbing Edward McCloskey. McCloskey had met up with the gang members on Carleton Street where the group shared a bottle of whiskey with him. They then charged him a dime for the drink.

He was then about to go home, when John Clyde said to him, “You must not go away.” He endeavoured to get away, however, and Clyde struck him on the eye with his hand and severely injured him. Martin Kelly assisted him. When they got him down they kicked him, but Eliza Nolan tried to save him, exclaiming, “Don’t kill him.” Clyde roared like a mad bull, and said he would take his life before he would leave the spot. When he got up he fell again and was then beaten by Kelly. He afterwards got away, Clyde threatening that if he informed of him he would make him suffer for it.

The gang were convicted and received various sentences. Elizabeth Nolan, for example, got two months in jail, much less than the others. Denis O’Dowd was a first time offender, was discharged. The rest got three months in jail.

The same weekend, a number of the Gang were caught in Ridout’s Bush by the police. Jeremiah Leary, Catherine Colgan, Annie Burns, Eileen Slattery, and Sarah Norton were all convicted and sent to jail Globe, August 16, 1859

George Gurnett sent Mary Wilson, Margaret Sherlock, Catherine O’Brien, and Emily Jane Ward to a month in jail for being drunk and disorderly in public. Globe, Aug. 23, 1859

City Police,

Before Geo. Gurnett, Esq.

Saturday, Sept. 17,

THE BROOK’S BUSH GANG.

Wm. McPherson, John Burns, Jeremiah Leivy, James Tuck, James Brown, Thomas Richardson, James Cochrane, John Eppison, Mary Anne Pickley, Mary Anne Walton, Sarah Fielder, Ellen McDonald, Margaret Hill, Mary Crooks, Mary Sheppard and Isabella Convony, all members of the notorious Brook’s Bush Gang, were then placed at the bar with two other men named Joseph Freeman and Wm. McCarty who were found in the company of the above, when Acting Sergeant Corke and the constables took them into custody on the previous day. They are not regular members of the gang. The females were sent to gaol fourteen days each, and the men a month each. Freeman and McCarty were each fined $4 with costs.

Acting-Sergeant Corke, one of the smartest men of the police force, made this arrest with four men, in the Bush at one o’clock on Saturday morning. Globe, September 19, 1859

Perhaps using the same house as the McLaughlins, Jane Ward was keeping a brothel when one of her women, Alice Thompson, stole Dr. Geikie’s horse and buggy. Globe, Oct. 5, 1859

That winter Jane Ward went to jail for a month for being drunk and disorderly. Globe, Feb. 20, 1860 She was right out of jail when she was sent back for a month for street walking and being drunk. Globe, March 26, 1860

Alleged Highway Robbery

Ann Maria Gregory, Sarah Fielder, Mary Ann Pickley, Jane Ward, Charles Gerue, and Andrew McGiven, members of the Brooke’s bush gang, were placed at the bar, on suspicion of being connected with the robbery of a person named John Dawes, on the Kingston Road, last Monday evening. Dawes unwisely accompanied Sarah Fielder into Brook’s Bush and then went with her to Cornell’s Tavern on Kingston Road. Afterwards Fielder and Dawes went back to the bush where one of the men there accused Dawes of having sexual relations with his wife and attacked Dawes with a stick. While Dawes lay on the ground Charles Gerue and Andrew McGiven relieved him of his belongings. Globe, August 24, 1860

Andrew McGuire and Jane Ward were charged with stealing James Todd’s watch in Brook’s Bush. Todd was visiting from Orangeville and went to the Bush for a “visit”. The Gang invited him to drink whiskey. At this time there were a number of girls present, one of whom, Jane Ward, put her arm around my neck and placed her other hand in my trouser’s pocket and took [my wallet]. His watch also went missing. Globe, October 2, 1860

1861 The City police were officially allowed to go into the Township of York to arrest suspects, particularly the Brook’s Bush Gang. The boundary of the City of Toronto was the Don River until 1884 when Riverside and Leslieville became part of the City of Toronto under the name “Riverdale”.

It will be seen by Sec. 3, just referred to, and as afterwards mentioned, that if the warrant is addressed as in No. 2, ‘ To all or any of the constables or other peace officers of the city of Toronto,’ (the territorial division within which the same is to be executed.) that the warrant cannot be executed beyond the city : but if it be addressed as in Nos. 3 and 4, above given it may be executed by any constable of the city, either in the city or in any part of the united counties of York and Peel ; and one or the other of these directions should, therefore in every case be adopted to enable the constable to arrest such vagrants as compose the Brooke’s Bush gang, and such other characters and thieves as haunt the outskirts of the city.[8]

Andrew McGuire and Alice Thompson were remanded on charges of robbing James Todd and sent back to jail. The police hadn’t yet found Jane Ward. Globe, Oct. 8. 1860 Sgt. Redgrave captured Jane Ward and five others, both men and women, in Brook’s Bush. Globe, Oct. 12, 1860 In court, Jane Ward claimed that James Todd alias James White, an ex-con, had turned over his watch to her “to take care of”. She claimed Todd was a Gang member who had been hanging out in the Bush for years. Globe, Oct. 13, 1860

1861 On March 30, Duck hunters found the body of John Sheridan Hogan, partially decomposed, caught in a tree branch in the marsh at the mouth of the Don River. John Sherrick and Jane Ward went on trial for the murder of Hogan. After two days deliberation, they were found not guilty. Sherrick had been able to produce an alibi. Sherrick had formerly been a member of another criminal outfit, the Markham Gang, which had spread wide tentacles across southern Ontario, friends who were willing to help a friend in need.

James Browne went on trial separately for the murder of Hogan. After an hour’s deliberation, the jury delivered a verdict of guilty and Chief Justice Draper sentenced Browne to be hung on December 4, 1861. An appeal by Browne’s layer for a new trial was heard and the execution of Browne was deferred pending the outcome of the appeal.

1862 Browne went to trial for Hogan’s murder a second time. He was again found guilty and sentenced to be hung on March 10, 1862. Many believed Browne was innocent and was set up by the real killer, Jane Ward, to take the fall.

“James Browne was executed at the old jail on Monday, the 10th March, 1862, for the murder of Mr. J. S. Hogan, M.P.P.

The latter had disappeared about the 1st December, 1859, and the Government subsequently offered a reward for his discovery, or that of his body, and commissioned Detective Wardell, of the Toronto police force, to trace his movements. He went to several American cities, but could find no trace of him, and the matter was almost forgotten.

About sixteen months after his disappearance a human skeleton, having yet some flesh on the bones and enveloped in male attire, was found in the marsh. The clothing was identified as that of Mr. Hogan, and an abandoned woman, one of the old Brooks’ bush gang, named Ellen McGillick, made a statement to Detective Colgan which led to the arrest of Brown. She stated that she had witnessed the murder of Mr. Hogan on the King street Don bridge one night in December 1859, by another abandoned woman named Jane Ward, Brown and two other men named Sherrick and McEntameny, the last-mentioned of whom had meanwhile died.

Browne, Sherrick and Ward were arrested, and McGillick’s evidence was to the effect that Ward had struck Mr. Hogan on the head with a stone tied in a handkerchief, when Brown and Sherrick robbed him and threw him into the river. Her evidence was partially corroborated by Maurice Malone, Dr. Gamble, and others.

Police Magistrate Gurnett committed the three for trial, which took place before the three for trial, which took place before the late Chief Justice Draper in April 1861. Mr. James Doyle, counsel for the prisoner, succeeded in establishing an alibi for Sherrick, several witnesses swearing that at the time at which the murder was alleged to have been committed he was living at Clover Hill, 50 miles from Toronto. The result was that the jury acquitted Sherrick and Ward. Mr. Doyle offered the same evidence to show that McGillick’s statement was unworthy of credence, but the Chief Justice ruled it out.

The jury found Brown guilty, but Mr. Doyle succeeded in getting a new trial, when Brown was again found guilty and sentenced by Mr. Justice Burns to be hanged on March 10, 1862.

The late Mr. Henry Eccles prosecuted at the first trial, and the late Chief Justice Morrison and the late Mr. Richard Dempsey at the second.

When sentence was passed upon him Browne declared his innocence. He had a dogged and sullen aspect, which was made more obnoxious by a scar on his nose caused by disease. He was born in Loulam, Cambridgeshire, Eng., and was 32 years old years of age when executed. He expressed contrition before his death, and declared his innocence unswervingly to the last, and with such earnestness that the ministers who attended to him, among whom were Rev. H. J., afterwards Dean Grasett, and Revs. Edmund Baldwin and S. J. Boddy, expressed their belief in his innocence. He was executed at the old jail, before an immense concourse of people, whom he addressed as follows:

‘This is a solemn day for me, boys. I hope this will be a warning to you against bad company. I hope it will be a lesson to all young people, old as well as young, and rich and poor. It was that brought me here to-day to my last end, though I am innocent of the murder I am about to suffer for. Before my God I am innocent of the murder. I never committed the murder. I know nothing of it. I am going to meet my Maker in a few minutes. May the Lord have mercy on my soul. Amen. Amen.’

The “Amen” was echoed by a few near the scaffold. When he was launched into eternity three or four strong spasms shook his frame and then all was over. The body was delivered at the request of deceased to Mr. Irish for burial. The crowd was not as large as that which witnessed the execution of Fleming and O’Leary. The fair sex was largely represented.”[9]

1864 John Smith had been violently attacked near the Don River during a heavy rainstorm. Two men sprang out of the ditch and struck him hard on the head with a stick. He dodged but fell. Smith, a strong active man, got back up, grabbed the fallen cudgel and struck one of his assailants down. He tripped the other and then Smith took off running. He reported the attack to the police. By that time the Brook’s Bush Gang was believed to have been broken up. Globe, May 10, 1864

Jane Ward died. A Celebrity Gone Jane Ward, one of the women connected with the murder of the late Mr. Hogan, M.P.P., died on Sunday last at Chippawa. This woman was one of those who knew most about the perpetration of the murder, but, as far as we can ascertain, she died without divulging anything that could clear up the mystery which still surrounds that dreadful crime. She protested, however, that the Unfortunate man Browne, who died on the gallows for the crime, had nothing to do with it other than belonging to the gang, the members of which did the deed amongst them. Globe, Sept 16, 1864

The body of Mary Ann Pickley, a well-known outcast, was discovered near a haystack next to Fort York by one of the sergeants stationed there. The corner’s verdict was death from drunkenness and exposure. Since the gang was broken up by the police, she has been living here and there and everywhere, but mostly in gaol, from which place she was liberated on Wednesday morning last, after two month’s imprisonment…Of the “Brook’s Bush Gang” she is nearly the last, a few short years having carried almost the whole of them to their graves, either in this or some other equally shocking manner. Globe, Nov. 18, 1864

1865 Workers in Hamilton found the skeleton of a man about 30 years old in a drainage pipe near the former home of Allen Murphy, father of Dick Murphy (member of the Brook’s Bush Gang). Police and coroner believed the body was that of a drover named Alexander “Sandie” McPherson, who went missing in September 1851. On April 14, 1861, while the Hogan murder investigation was ongoing, the police found two skeletons near the Don bridge, according to reports. Ellen McGillick had told Toronto police that the Brook’s Bush Gang had murdered tow people there in September 1859. According to McGillick, They were all proceeding in the direction of the Bush, having with them a jug of whiskey. Near the railway crossing on the Kingston Road, they sat down to have a drink all round. While they were imbibing, one of the “gang” exclaimed significantly to the others, “It’s a pity he can’t get up and have a glass with us.”

McGillick thought that this meant someone had been murdered and buried near where they were sitting (near the level crossing at McGee Street and Queen Street). Police went with shovels to the spot but didn’t find any human remains of, many believed, Sandie McPherson from Reach Township. As a drover and cattle dealer, McPherson knew Dick Murphy from the St. Lawrence Market where Murphy was a butcher. McPherson left the Market after dark one night in September 1859. He was quite drunk after a visit to John Cornell’s Hotel, East Market Square where Cornell had paid him a large sum of money for his cattle. Friends noted that McPherson was liable to be led astray when he was under the influence of liquor. The Hamilton body was believed to be that of the missing drover. Dick Murphy was out of the long arm of the law, being somewhere in the United States, possibly Chicago. Globe, September 8, 1865

1866 Samuel Harris, head sales person at John Barron’s shoe store in the St. Lawrence Market, was robbed near the Don Bridge where John Sheridan Hogan had been murdered. Two Brook’s Bush gang members struck him from behind and stole his watch and chain. The victim came to and defended himself fiercely against his assailants who took to their heels, escaping from Harris and two teenagers who stopped to help the robbed man. Ottawa Times, November 17, 1866

1868 Kate Colgan, the last of the Brook’s Bush gang, was arrested for breaking Mr. Lloyd’s windows. She held forth to the effect that she was the quietest woman in the world, and had been sadly abused by the police. Globe, October 26, 1868

1870 Catherine Colgan was involved in the infanticide of a friend’s new-born at the Toronto Lying-in Hospital. Globe, March 15, 1870 In December she was charged with being drunk and disorderly and fined $3 or two months in jail.

1872 The court convicted Kate Colgan on charges of being drunk and disorderly. She was fined $3 and costs or three months in jail. Globe, February 2, 1872

1873 In February Kate Colgan was charged with vagrancy but discharged. Later that year Catherine Cogan made quite a speech on the subject of her past conduct and was discharged (by the court). Globe, September 6, 1873

1874 Jane Davis and Kate Cogan (Colgan) were fined a dollar each and court costs or six months in jail at hard labour. Globe, December 8, 1874

1875 Kate Cogan (Colgan) was charged with vagrancy sent to prison and sent to jail on old charges. Globe, June 25, 1875

1885 Kate Cogan was convicted for stealing a cruet and some jackets and was sent to the Mercer Reformatory for six months. Globe, May 5, 1885

1888 Catherine Colgan (Cogan) was remanded for vagrancy. (Globe, June 8, 1888) This is the last mention of her in the Globe.

1906 Trustee’s Sale of Valuable Freehold

Situate on

Logan and Carlaw Avenues,

in the City of Toronto.

Offers will be received by the undersigned up to the 4th day of June 1906, for the purchase – in one or several parcels – of that valuable tract of city property lying between Logan and Carlaw avenue, situate a short distance north of Queen street, known as lot No. 2, plan 568A, on the east side of Logan avenue, containing about nine acres.

This property has a frontage upon Logan and Carlaw avenue each of about 600 feet. The depth between these streets is about 656 feet.

This property, which has been in the possession of the Brooke estate for upwards of 80 years, and is now for the first time offered for sale, affords an exceptional opportunity to builders, manufacturers, and others.

Terms – The purchase money to be payable in cash on completion of purchase or at the purchaser’s option 50 per cent thereof may remain outstanding on mortgage on the land with interest at 5 per cent.

Cassels, Brock, Kelley and Falconbridge.

19 Wellington St. West Toronto.

Dated 18th May 1906. Toronto Star, May 19, 1906

1940 Saturday Night Book Review

William Arthur Deacon, Literary Editor

Enthusiastic Expatriate

Adventures, Travels and Politics. By A. C. Forster Boulton; Copp, $2.50.

A. C. Forster Boulton: I remember as a small boy catching speckled trout in the brooks in Rosedale. East of the Don River and north of the Kingston Road was a wilderness. Sometime in the sixties of the last century a gang of robbers infested that district. They were known as Brook’s Bush Gang, but were finally captured and punished. Now houses and streets cover the whole neighbourhood and security reigns where once was lawlessness and crime.” Globe and Mail, February 17, 1940

2003 James Brown, 1862

Labourer born in Soham, near Cambridge, England, on Feb. 23, 1830; in 1852, immigrated to the United States; in 1854, moved to Toronto to find work in shipyards of Canada West; fell in with group known as the Brook’s Bush gang that prowled woods in Don Valley near Toronto; on Dec. 1, 1859, accused of robbery-murder of John Sheridan Hogan, newspaper-owner and member of legislative assembly; convicted and executed; 5,000 attended hanging; Toronto’s last public hanging. Globe and Mail, March 10, 2003

Some other sources:

George H. Ham, Reminiscences of A Raconteur between the ’40s and the ’20s, The Musson Book Company Limited, Publishers Toronto Copyright, Canada, 1921 pp 166-167

Harold Horwood, Ed Butts, Ch. 10 Brooks Bush Gang, Bandits and Privateers: Canada in the Age of Gunpowder, 1988

Adam Wilson, “The constable’s guide: a sketch of the office of constable”, 1861 accessed at http://www.archive.org/stream/cihm_10903/cihm_10903_djvu.txt , Nov. 9, 2009

David Boyle, The Township of Scarboro, 1796-1896, William Briggs, 1896, pp. 231-233. Accessed at http://www.archive.org/stream/townshipofscarbo00boyluoft/townshipofscarbo00boyluoft_djvu.txt Nov. 9, 2009

For more about Daniel Brooke Jr. and the Brooke Building:

https://www.torontojourney416.com/daniel-brooke-building/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniel_Brooke_Building

https://nowtoronto.com/news/hidden-toronto-daniel-brooke-building/

[1] The Toronto Jail was built between 1862 and 1865 although a jail has stood on the site since 1858. Designed by architect William Thomas in 1852, its distinctive façade in the Italianate style with a pedimented central pavilion and vermiculated columns flanking the main entrance portico is one of the architectural treasures of the city and one of very few pre-Confederation (1867) structures that remains intact in Toronto. For example, it is over thirty years older than Toronto’s Romanesque Old City Hall.

[2] Women were most commonly charged with assault and drunkenness and often fined or served short terms. A fine of ten shillings or the alternative of seven days’ gaol was the average. With this representing about a week’s wage many more women than one might suspect were imprisoned, albeit for a very short stretch.

Some cases were more serious. A most callous assault on a shopkeeper in Birmingham had no alternative of a fine. 20-year-old Amy Gill was sent down for two months for attacking a woman who had caught her shoplifting. Along with two accomplices she pulled two good handfuls of hair from the head of her accuser and was said to have used the vilest language ever heard in Birmingham.

Another common charge against women was prostitution. Ladies of the night would target drunken men and lifted more than their skirts, with the wallets and watches of punters the most common targets.

Other common female offences, no longer a problem in today’s society, included: frequenting – loitering with intent; skinning – stealing clothes from a child’s back, and ringing the changes – falsely claiming to have handed over a coin of higher denomination than was really the case. Stealing clothes from clotheslines was the last resort of several old women whose job prospects were minimal. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/familyhistory/get_started/victorian_mugshots_gallery_04.shtml

[3] Play BAD AS I AM by Tara Beagan

[4] HOGAN o@ca.on.york.toronto.globe_and_mail 2003-03-10 published

Died This Day – James BROWN, 1862

Monday, March 10, 2003 – Page R7

Labourer born in Soham, near Cambridge, England, on February 23, 1830; in 1852, immigrated to the United States; in 1854, moved to Toronto to find work in shipyards of Canada West; fell in with group known as the Brook’s Bush gang that prowled woods in Don Valley near Toronto; on December 1, 1859, accused of robbery-murder of John Sheridan HOGAN, newspaper-owner and member of legislative assembly; convicted and executed; 5,000 attended hanging; Toronto’s last public hanging.

[5] Susan Goldenberg is a Toronto writer

[6] Ryan Bowman, They Died in the Care of the County, Guelph Mercury, July 6, 2013

[7] David Boyle, The Township of Scarboro, 1796-1896, William Briggs, 1896, pp. 231-233. Accessed at http://www.archive.org/stream/townshipofscarbo00boyluoft/townshipofscarbo00boyluoft_djvu.txt Nov. 9, 2009

[8] Adam Wilson, “The constable’s guide: a sketch of the office of constable”, 1861 accessed at http://www.archive.org/stream/cihm_10903/cihm_10903_djvu.txt , Nov. 9, 2009

[9] Robertson, Landmarks, p. 263

Very great research Joanne:) 👏