By Joanne Doucette

When Luella Cooper was born on June 30, 1858, in Maryland. Her father, William, was 21, and her mother, Mary, was 20. This was before the Emancipation Declaration which freed slaves on January 1,1864. It appears that her father may have been enslaved although there are records of Coopers as free people of colour in at that time. They were the descendants of white fathers and black mothers as was Luella. By the Civil War almost half of Maryland’s black population were free people of colour. Maryland stayed in the Union during the Civil War although many supported slavery. Because it stayed in the Union, the Emancipation Proclamation didn’t apply to Maryland. Many people moved from Maryland to Washington, D.C. during the Civil War both because of employment opportunities and to be free. In the fall of 1864 Maryland voted to free its enslaved people.

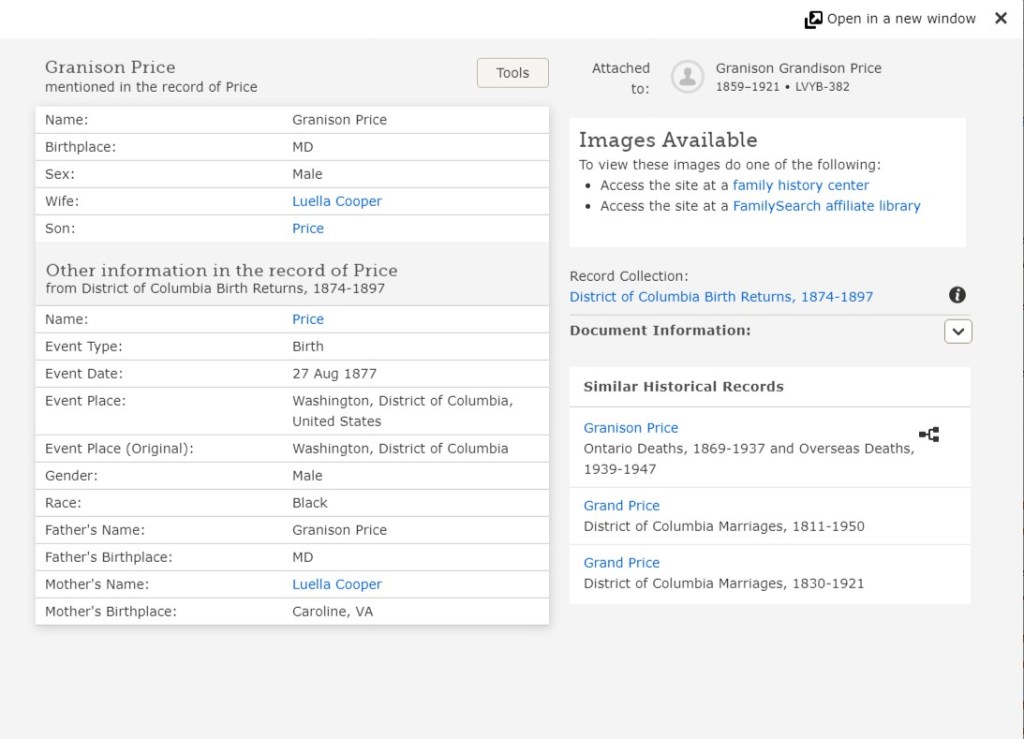

Granison Thomas Price or “Grandison” was born in Maryland in 1850, the son of Eliza, a black slave and Grandison Price, a farmer of moderate means in Rowlesburg, West Virginia, USA. His father was married to Abigail Ford and had a large family of children with her, as well as more children with Eliza, including William (1855) and Abram (1849). He had a white half-brother also named Grandison or Grandison. Many family trees confuse the two men.

West Virginia did not support slavery and withdrew from the Confederacy, separating from the rest of Virginia which strongly supported slavery. In West Virginia most slave owners were small landowners like Grandison Taylor Price, the father of the subject of this document. Grandison Thomas Price was still living in West Virginia when it became the 35th state admitted to the Union on June 20, 1863. His father, Grandison Taylor Price fought in the West Virginia Infantry for the Union in the Civil War.

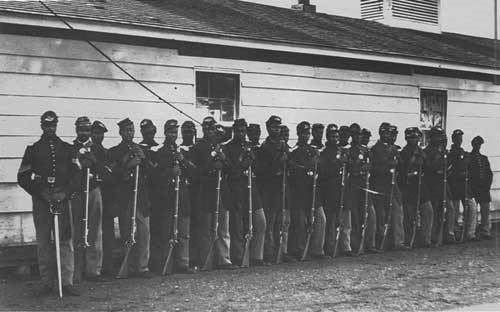

A “G. Price” served with the 11th U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery, enlisting on October 8, 1863. He is described at 5’7” tall with dark hair, dark eyes and a dark complexion. He was a waiter. On October 25, he was appointed a sergeant (U.S., Colored Troops Military Service Records, 1863-1865 for G Price). It seems likely that this was Grandison Price. This unit served mostly in Louisiana and Texas. He was probably mustered out of service with his regiment in 1865 at New Orleans. Grandison Price is listed at Perry County, Alabama in the 1866 Alabama State Census “Coloured Population”. In 1870 Grandison Thomas Price living in Reno, West Virginia, USA.

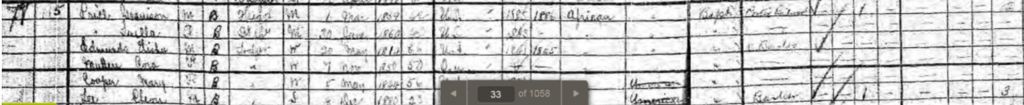

Luella Cooper was living in Washington, District of Columbia, USA, in 1870 at the time of the US Federal Census. She married Grandison Thomas Grandison Price on June 16, 1875, in the District of Columbia, USA. He was a messenger for the US Government. Both were listed as “mulatto”.

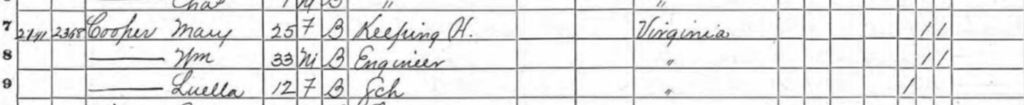

In the 1880 US Census for Washington in the District of Columbia, William Cooper is still listed as an Engineer. William was 46; Mary 37. The family are all listed as “mulatto”. William’s parents were born in Virginia. Mary Cooper is listed as “Keeping House” Both William and Mary were born in Virginia. Louella is listed as “Lewelyn Price, 23, at home”; Grandison was 25 and worked as a Government Messenger. Luella and Grandison’s only child, a son, was born on August 27, 1877, in Washington, District of Columbia, USA and apparently died in infancy as he is not in any other record. They later but adopted a son, Robert C. Lynch, born in 1881 in the USA. Robert J. Lynch became a waiter on the railway.

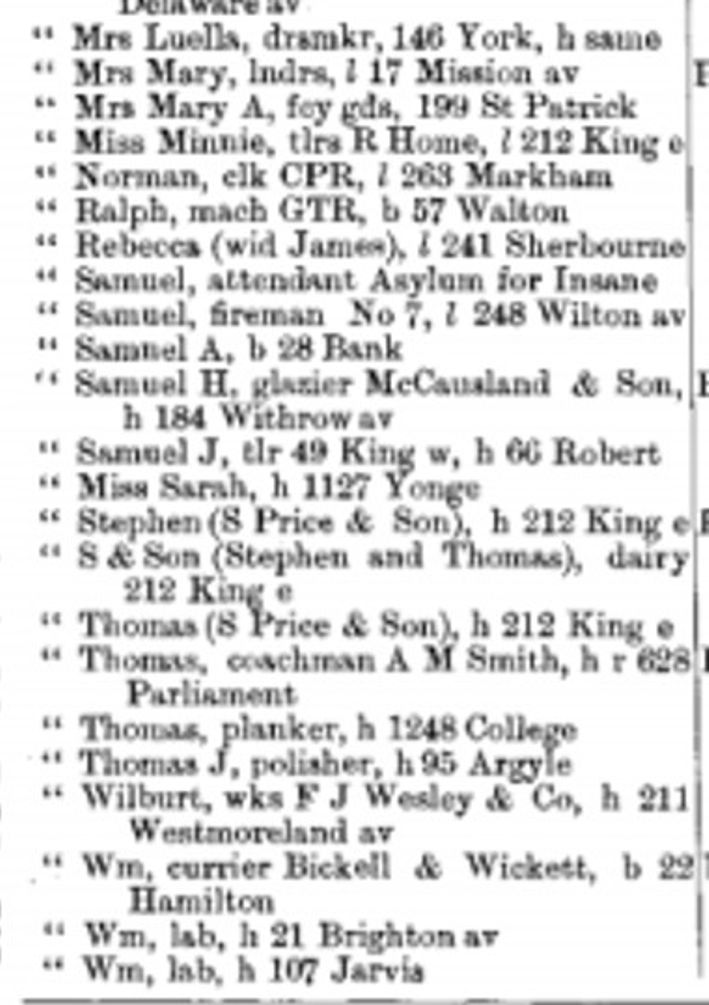

When the Civil War was over, black Americans returned to the US though not to the South. Instead they moved to the large cities of the American north and mid-west: Detroit, Pittsburgh, Chicago, etc. While some stayed most black people in Leslieville joined the exodus. Others came north to escape Jim Crow laws and the violent racism of the South. Some time between 1877 and 1885 the Prices moved north to Toronto. By 1887 the Prices were living in Toronto where Luella was working as a dressmaker. They lived downtown on York Street. The heart of the business district now was the heart of Toronto’s black community then. They were members of the First Baptist Church when they lived in Toronto. The Prices were devout, warm and generous people. They must have saved every penny and worked long hours to build up savings to invest in their businesses.

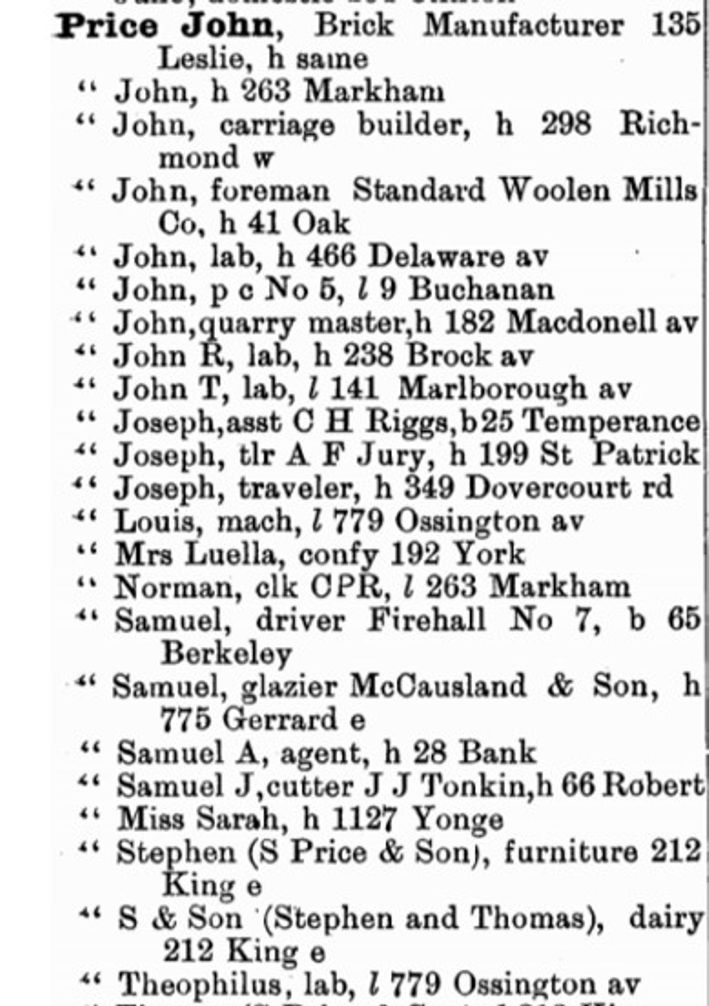

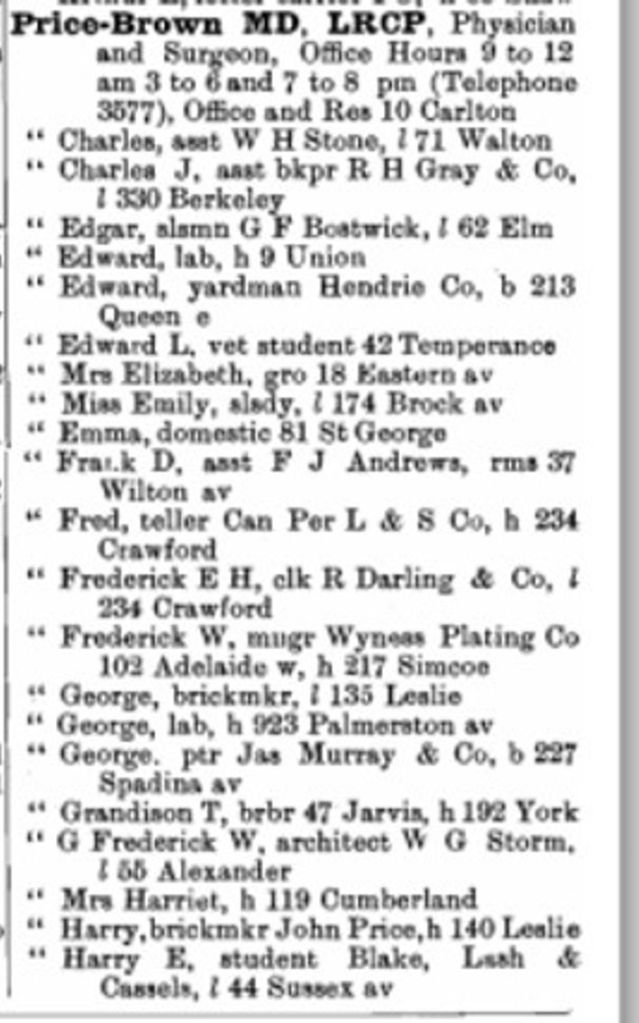

In R L Polk & Co.’s Toronto City Directory 1888 Grandison Price is listed as a barber with a business at 39 Jarvis Street, but residing at 345 Parliament Street. He was a barber in 1891 but soon became a porter on the railroad and worked for the CPR. In 1892 the Prices were living at 192 York Street, the heart of Toronto’s black community, while Grandison worked in his shop on Jarvis. In the Toronto City Directory of 1894, Louella is listed as a dressmaker living at 146 York with her business in the house. For many years she ran a boarding house. Prominent members of that community, including Elisha Edmunds and John Hubbard, boarded with the Prices. By 1893 Luella had her own restaurant at 192 York Street. By 1896 they were living on Morse Street in the East End as the wealthy landowners of York Street cleared the houses to build offices and factories.

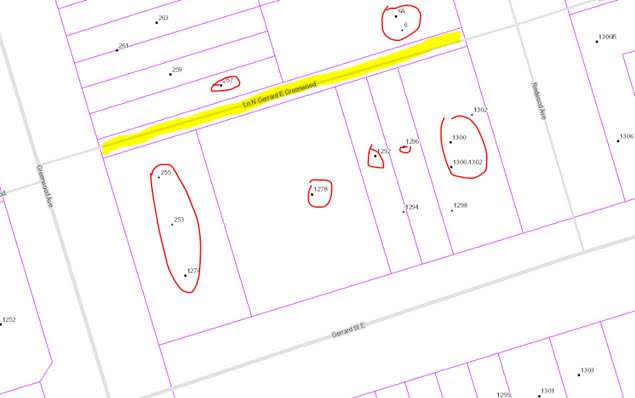

By 1898 Grandison Price was a conductor on the CPR but sometimes worked as a porter as well. The 1901 Census shows Mary Cooper, probably Luella’s mother, living with them in the Prices in their boarding house. In 1910 they were still living at 105 Morse Street. That year Grandison and Luella built a tiny frame house near Greenwood and Gerrard, in Toronto’s east end and moved to their new home at 6A Redwood Avenue.

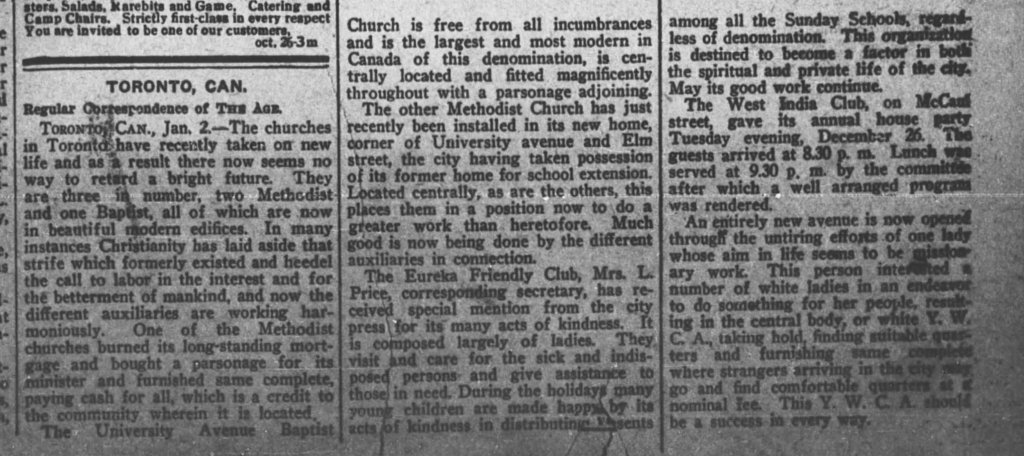

In 1910, Luella Price and a handful of other women met in her small frame house at 6A Redwood Avenue to form the Eureka Club. It was also known as the “Eureka Friendly Club”. They saw one individual in need in their community and put their resources together to meet that need. Their motto was “Not for ourselves, but for others”.

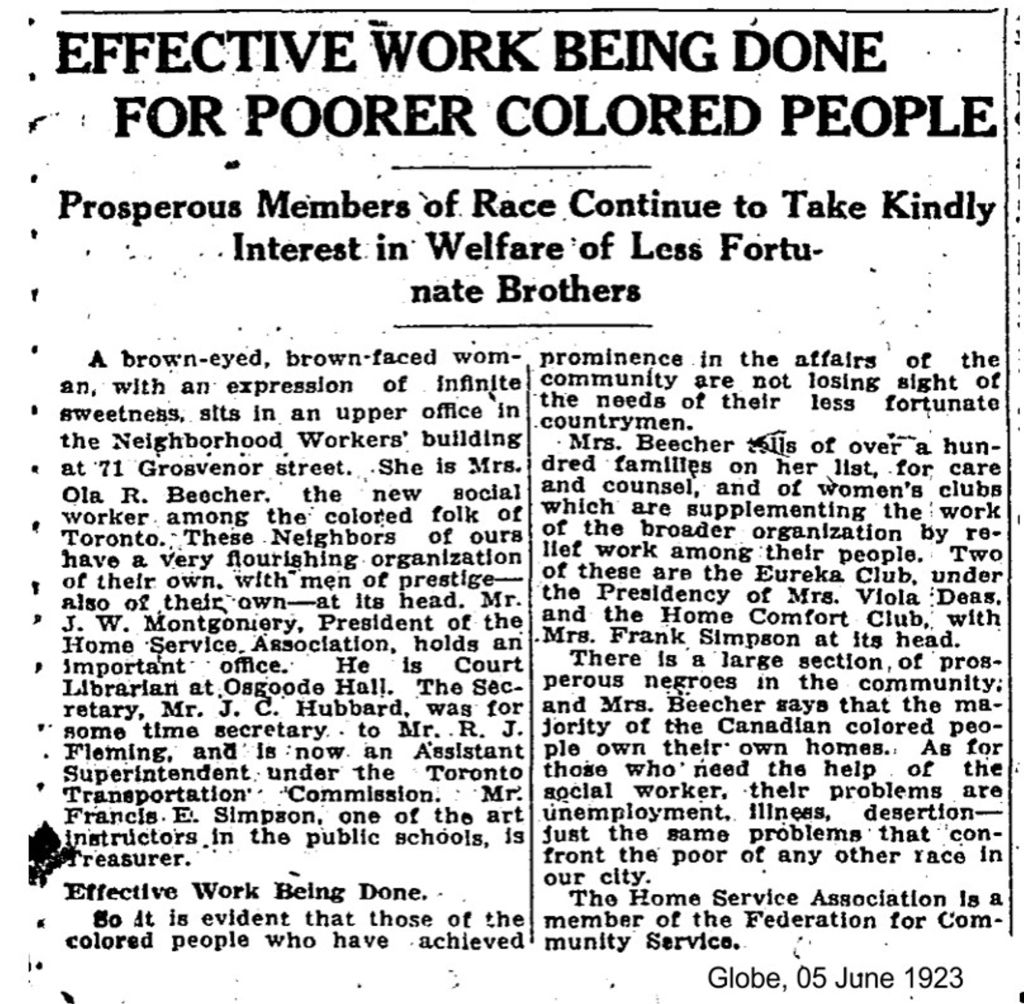

As a Globe article of June 5, 1923 said:

Effective Work Being Done. So it is evident that those of the colored people who have achieved prominence in the affairs of the community are not losing sight of the needs of their less fortunate countrymen.

Poverty was not a black problem, but a human problem:

As for those who need the help of the social worker, their problems are unemployment, illness, desertion – just the same problems that confront the poor of any other race in our city.

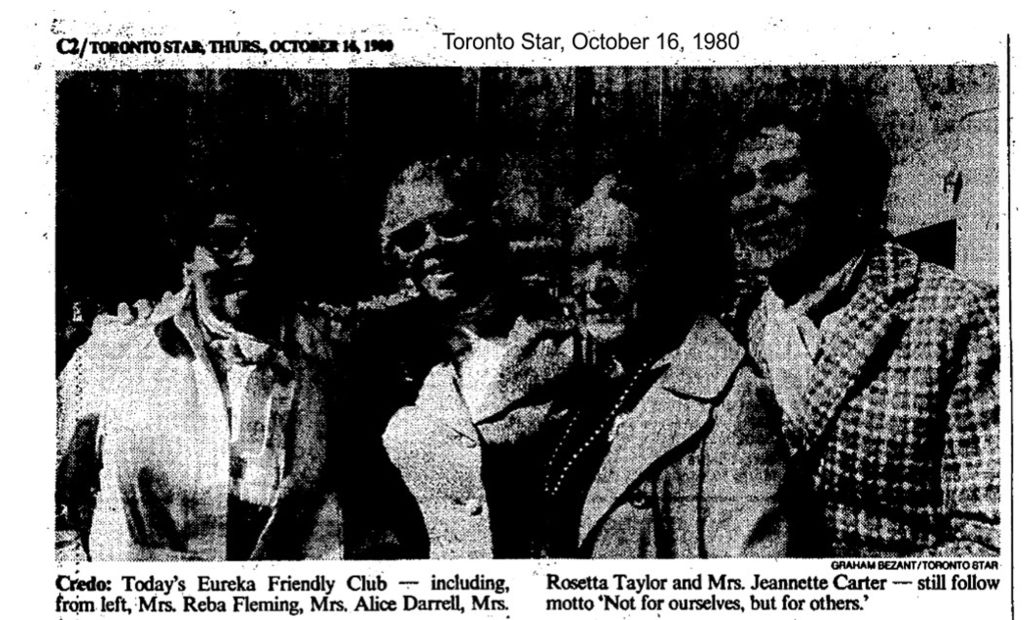

The women of the Eureka Club were determined to reach out with assistance, tactfully and privately, on a one-to-one basis. Whatever the need was they quietly met it to the best of their ability. They never sought publicity and, by and large, they didn’t get it. The Toronto Star of October 16, 1980 was an exception:

The Eureka group has done everything: Assisting with rent, hospital or funeral payments, visiting shut-ins, distributing food and clothing, supplying glasses for children, making cancer pads; awarding scholarships to students entering university, coating a wheelchair to Bloor-View Children’s Hospital, assisting churches in purchasing hymnals…Their work, ever since that first session 70 years ago to help one needy individual, has been largely in the black community, but not confined to it.

The Eureka Club was never larger than eighteen women. Viola Deas was another of those involved in the Eureka Club. Her husband Horatio, like many of the spouses of the Eurekas, was a railway porter as was Luella’s husband, Grandison. This may have been one of the things this handful of women had in common as, in this case, it was not their church. They came from all denominations: Anglican, Methodist, Baptist, Congregational, etc. Some lived in the East End. Viola Deas was later to live on Caroline Street. In 1980 at its 70th anniversary, the Eureka Friendly Club was the oldest black women’s organization in Ontario.

The Prices like most in the black community worked hard, saved their money and used it wisely. Most owned their own homes. By 1914 the Prices had earned enough money for Luella to take a vacation. On May 4, 1914 she sailed aboard the Bermudian from Hamilton, Bermuda to New York City. From there she probably took a train to Toronto.

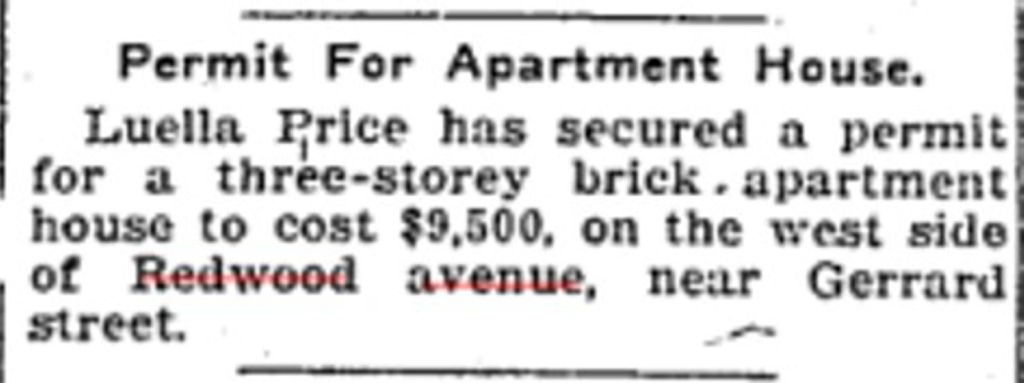

In 1915, at the age of 57, Luella Price had secured a permit for a three-storey brick apartment house to cost $9,500,at 6 Redwood Avenue. (Toronto Star, Feb. 6, 1915)

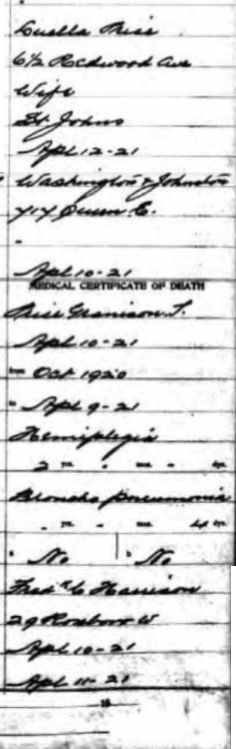

Grandison Price passed away on April 10, 1921, before Louella. He had had a stroke some years earlier and was partially paralyzed. He been in the Hospital for Incurables since October 1920.

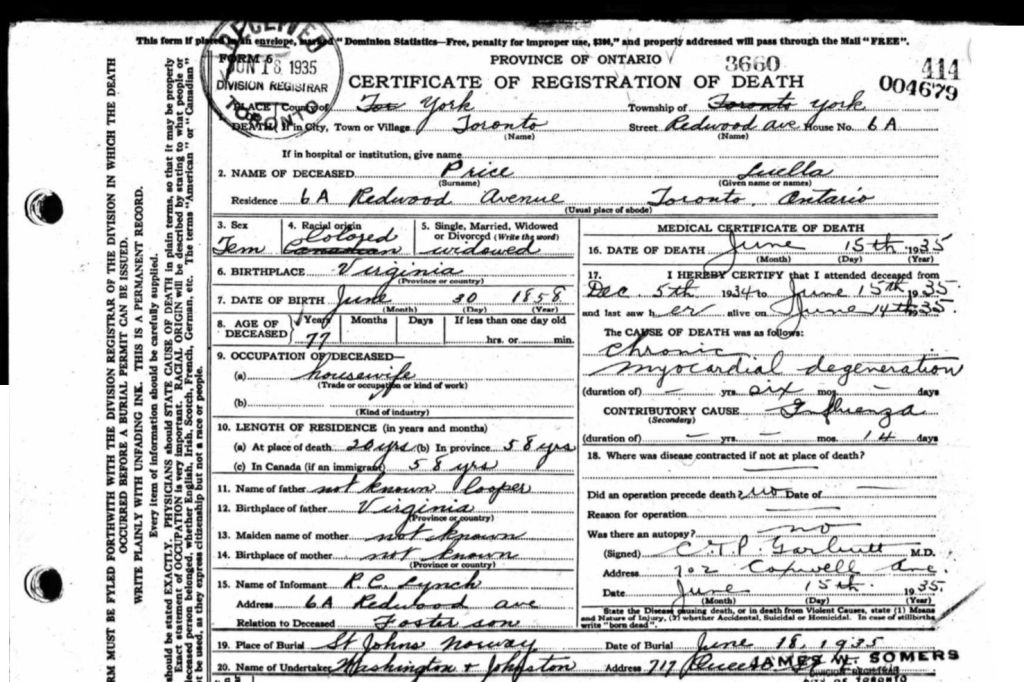

Luella Cooper continued to live in her apartment building on Redwood Avenue until she died on June 15, 1935, in York, Ontario. She was 76 years old. Her foster son, Robert C. Lynch reported her death. She was buried beside Grandison in the St. John of Norway Cemetery, on June 18, 1935. On her death certificate the neat handwriting of Robert J. Lynch has her “racial origin” as “Canadian”, but an official has crossed this out and written in “Coloured”.

The Neighbourhood

Documentation